The history of Milwaukee is anything but dry. Water, in fact, runs through it like a river, constituting an element so critical that imagining the community without it is virtually impossible. Whether for transportation, industry, recreation, sanitation, or simply as the backdrop for daily life, water is the fluid medium in which Milwaukee evolved from the embryonic settlement of the 1830s to the metropolis of the twenty-first century. It continues to percolate deep into Milwaukee’s civic subconscious, adding a liquid dimension to the identity of the city and all its citizens.

The physical setting itself was created by water—in its crystalline form. Sheets of ice advanced and retreated across the site of Milwaukee for nearly a million years, smoothing the land surface and creating new drainage patterns. One massive lobe of the glacier scooped out Lake Michigan’s basin, and that lobe’s dying edge left a series of north-south ridges that are among Milwaukee’s dominant landscape features. The easternmost of those ridges, which today virtually defines the city’s East Side and its North Shore suburbs, formed a rampart that the ancestral Milwaukee River could not breach for more than thirty miles on its southerly course from Ozaukee County. Only when it reached the pre-glacial valley of the Menomonee River and captured the smaller Kinnickinnic was the stream able to punch its way through to Lake Michigan.[1] It was at that outlet that Milwaukee came to life.

A long procession of native peoples made their homes where the river met the lake. The location gave them access to canoe routes; a ready source of fish and waterfowl; an abundance of reeds, rushes, and other building materials; and sprawling beds of wild rice, or manomin, for sustenance. At the dawn of white settlement in the 1830s, there were eight native villages within three miles of the river mouth, all of them sited on or near one of the area’s three waterways: the Milwaukee, the Menomonee, or the Kinnickinnic.[2]

The first white settlers saw an entirely different set of advantages. In the Age of Sail, when the standard route carried travelers up the Great Lakes from Buffalo, harbor potential was the primary criterion for any aspiring urban site. Milwaukee qualified generously. In its inaugural issue (June 27, 1837), the Milwaukee Sentinel described the tiny community’s major attraction:

Milwaukee Bay affords the best and safest harbor on Lake Michigan. It is formed by a beautiful indentation of the Lake, about three miles in depth, being locked in by northerly and southerly projecting points; and within this curve, 300 vessels might lay at anchor with ease and safety.

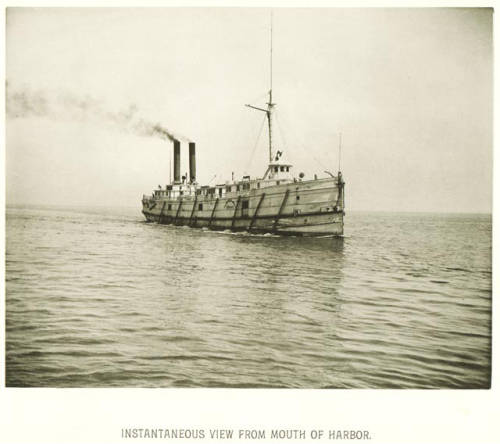

The bay may have promised “ease and safety” when the lake was calm, but the Milwaukee River, in those pre-breakwater days, played the larger role as a harbor of refuge in rough weather—and as the primary landing point for both cargo and passengers. The same 1837 Milwaukee Sentinel account gave the stream a qualified endorsement: “Except on the bar at its mouth, the river has plenty of water, for a distance of three or four miles, to float the largest ship that navigates these inland seas.” That troublesome sandbar, formed by the contending currents of river and lake, impeded traffic until Milwaukee, after years of lobbying, secured federal funds to improve its harbor. The most important project, completed in 1857 with largely local support, was the “straight cut,” which severed the peninsula known as Jones Island and created a new river mouth one-half mile north of the original outlet. Once the new mouth was navigable, the 1857 Milwaukee city directory could boast that “Milwaukee Harbor is the safest, the roomiest and easiest of access, of any on the entire chain of Lakes.”[3]

With its front door wide open and access to the state’s interior improving rapidly by plank road and then railroad, Milwaukee began to realize what the community’s leaders had long considered its manifest destiny. The city, they believed, would become the commercial capital of Wisconsin and its principal point of exchange between finished goods from the East and farm products from the interior. In his 1848 inaugural address as mayor, Byron Kilbourn, the west side’s founder, described that economic role as “the rich prize which nature awarded and designed to be hers.”[4] Milwaukee seized the prize as an outlet for grain, particularly wheat. In the early 1860s the city was the largest shipper of wheat in the world, a distinction that flowed directly from its favored position on water.[5]

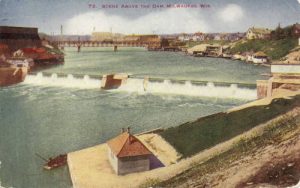

If water served as a pipeline for newcomers and a medium of commerce for the region, it was also a critical source of power for pioneer industries. Long before there were practical steam engines or rudimentary internal combustion engines, water provided much of society’s muscle. Milwaukee’s first settlers built dams and erected mills wherever a watercourse had even a modest drop, harnessing its hydraulic potential to produce flour, lumber, and textiles. Wauwatosa was originally known as Hart’s Mills, and even tiny Oak Creek was yoked to a millwheel.

As the area’s largest stream, the Milwaukee River supported the most ambitious enterprise. In 1839 Byron Kilbourn, who had cut his professional teeth on Ohio canal projects, broke ground for what he hoped would be a canal connecting Milwaukee—specifically his west side of Milwaukee—with the Mississippi River by way of the Rock and Illinois Rivers. (In a sign of things to come, the shovel broke when Kilbourn attempted to use it, prompting a string of expletives that shocked some bystanders.[6]) Political opposition killed the project soon after Kilbourn had finished a dam at North Avenue and a little more than a mile of canal below it. Undaunted, he and his associates converted the aborted waterway into a millrace fed by the impoundment above the North Avenue dam. The result was Milwaukee’s first industrial district. Known simply as “the Water Power,” by 1849 the millrace supported factories that made axes, woolen goods, pails, sashes and doors, machine shop supplies, carriages, leather, and flour. Processed wheat became the local specialty. In 1857 Kilbourn’s ditch drove five flour mills that turned out 120,000 barrels a year. Hydraulic turbines were eventually supplanted by steam engines; in 1885 the millrace was filled in and paved over to become Commerce Street.[7]

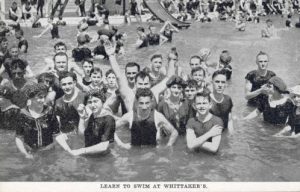

If industry prevailed below the North Avenue dam, the theme upstream was recreation. In a time of limited mobility and six-day workweeks, access to water for leisure-time pursuits had enormous appeal. Lake Michigan was considered too cold for all but the most intrepid, but the upper Milwaukee River was warm, protected, and easily accessible to thousands of city residents. Beginning in the 1870s, private operators developed a full suite of attractions. Three swimming schools utilized the deep water just above the dam. The Blatz brewery had a beer garden on the west bank at the foot of Burleigh Street—a site now occupied by Milwaukee County’s Pleasant Valley Park. Canoe clubs floated entire flotillas during races and regattas. Affluent German families, among them the Kerns, Uihleins, and Meineckes, built spacious summer homes on the upper river; the Kern estate is now Kern Park.[8]

Some of the most popular destinations would not have been out of place in the latter-day Wisconsin Dells. On July 4, 1896, a water slide called Shoot the Chutes opened on the east bank near North Avenue. Cars slid down a steep incline, splashed into the river, and were winched up the bluff for another round. Teenagers, especially, found the ride irresistible. “It is adventuresome enough,” reported the Milwaukee Sentinel (July 5, 1896), “to make it fascinating to young people, and there is an additional delight in the irresistible impulse with which the young man’s sweetheart clings to his shoulder just before the plunge.” Farther upstream, on the site of what is now Hubbard Park in Shorewood, a succession of amusement parks drew city-dwellers by the thousands. Known variously as Mineral Springs, Coney Island, Ravenna Park, and Wonderland, the park had different attractions under different operators, including a carousel, a water slide, and a state-of-the-art wooden roller coaster.[9]

Some entrepreneurs used only the river itself. A steam-powered water taxi provided service from the North Avenue dam to the upstream attractions for a fare of fifteen cents, and there were well-patronized night excursions on the river. The Milwaukee Sentinel (Aug. 4, 1879) provided a lyrical account of a bygone Milwaukee pastime:

Nothing can be prettier than the scene of a little steamer, with her head-light throwing a lurid glare ahead, slowly making her way up the river towing a barge in which are gayly-dressed maidens and young men passing through the salutary figures of the dance. And as the sound of soft music comes over the waters and dies away in the groves, the effect is indescribable.

Revelers with fewer pennies to spend could use the public parks planted along the river. Gordon Park lay just south of the Locust Street bridge; its major amenity was a popular swimming beach, with slides, an enclosed area for beginners, and a spacious bathhouse. Riverside Park (1890), directly across from Gordon, and Kern Park (1909), a few blocks south, lacked beaches, but both featured rustic paths that wound through the woods directly to the water’s edge.[10]

Although the river was busiest during the summer months, it attracted recreation-seekers in its solid state as well. After the canoes had been stored for the season and the bathhouse doors were locked, the emphasis shifted to winter sports: hockey, ice skating, sledding, and even more challenging activities; a full-sized ski jump atop the Gordon Park bluff drew daredevils from throughout the region. The Milwaukee Public Schools Recreation Division sponsored ice carnivals in the 1910s and 1920s that served a complete smorgasbord of winter sports activities. Milwaukeeans helped themselves, but they did not need organized events to enjoy the river. When the ice was good, they could skate from Capitol Drive nearly to the North Avenue dam—a distance of almost two miles.[11]

The ice closest to the dam was off-limits to skaters. In the later 1800s, before mechanical refrigeration crossed the commercial threshold, meat-packers, brewers, and virtually every householder depended on ice to keep their products and provisions from spoiling. Inland lakes provided most of the “hard water,” but the Milwaukee River was an important source as well, and much closer to its ultimate market. Massive icehouses rose on both sides of the river above the dam, insulated with sawdust and filled with cakes cut by hand on the stream below.[12] The harvest was renewable for as long as the temperature stayed below freezing.

A different resource was harvested from Lake Michigan. Beginning in the early 1870s, the Jones Island peninsula—pointing north rather than south after the 1857 straight cut—supported a village of commercial fishing families drawn largely from the Kaszuby region on Poland’s Baltic seacoast. Joined by German-speaking Pomeranians and a smattering of other groups, the Kaszubs harvested up to two million pounds of trout, whitefish, perch, cisco, and sturgeon every year, providing their fellow Milwaukeeans with a critical source of protein for decades.[13]

The waterfront village occupied a unique place in the city’s cultural geography. Settled largely without benefit of title and therefore subsisting largely without municipal services, Jones Island maintained a rural, even rustic, ambience as an industrial metropolis developed around it. The colony’s improvised street system, abundant saloons, and picturesque shoreline drew a steady stream of tourists from the mainland, including gourmands who came for the fish fries and artists attracted by the scenery. The colony’s population peaked at roughly 1,600 at the turn of the twentieth century. Its decline thereafter was rapid. Condemned for civic improvements in 1914, the fishing village shed residents until the last, Island native Capt. Felix Struck, was evicted “for reasons of port security” in 1943. With Struck’s departure, Milwaukee’s most distinctive urban village disappeared forever.[14]

Until some indeterminate point in the late nineteenth century, a rough balance might be said to have existed between Milwaukee’s water resource and the people who used it. The river was clean enough for swimming, the lake had plenty of fish, and the water was pure enough to drink. That condition of balance was due more to the elasticity of the resource than the foresight of its users, and it became increasingly precarious as the city’s population increased and its economy developed.

Drinking water was the first and most critical casualty. Since 1873, when public wells and backyard cisterns proved inadequate to the needs of a growing population, Milwaukee had drawn its water from Lake Michigan. A pumping station at the foot of the North Avenue bluff pulled untreated lake water from an offshore intake up the bluff and under the streets to a reservoir on an elevation west of the Milwaukee River—now part of Kilbourn Park. From there it flowed by gravity to homes and businesses in the central section of the city. The system worked satisfactorily for decades, but problems with water quality grew more serious; in 1910 the city began to chlorinate its drinking water.[15]

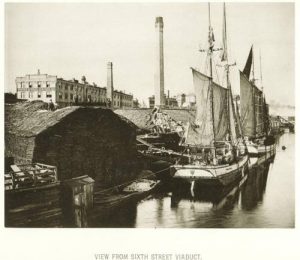

The problem was the Milwaukee River. The erstwhile artery of commerce became an open sewer in the later 1800s. Despite a network of intercepting pipes that conveyed sewage to a pumping station on Jones Island, both human and animal waste washed into the stream with every rain. Docking and dredging had slowed the current to a crawl, producing a slackwater estuary where the filth simply accumulated and, in hot weather, cooked. An 1881 visitor offered a graphic description of Milwaukee’s principal waterway: “It is a narrow, tortuous stream, hemmed in by the unsightly rear ends of street buildings and all sorts of waste places; it is a currentless and yellowish murky stream, with water like oil, and an odor combined of the effluvia of a hundred sewers.”[16]

Milwaukee “solved” the problem in 1888. The city dug a tunnel under the East Side to an outfall below the North Avenue dam, installed the world’s largest water pump in a handsome Cream City brick building on the lakefront (now Colectivo Coffee), and proceeded to flush the putrid river with fresh lake water. The stream’s health improved practically overnight, but the sewage plume regularly reached the city’s water intake in Lake Michigan. Seven people died of typhoid fever during a single week in 1916, and Milwaukeeans learned to live under frequent boil advisories.[17] It was not until 1925, when the city began to treat rather than simply dilute its sewage, that the problem was addressed at its root. The treatment plant was built on Jones Island, displacing scores of the few remaining fishing families but abating the scourge of water-borne disease for nearly 500,000 Milwaukeeans.[18]

The Menomonee River was, if possible, even more impaired than the Milwaukee. Beginning in 1869, the former marsh was filled in to become the most valuable industrial real estate in Wisconsin; packing plants, tanneries, machine shops, lumberyards, and an assortment of factories provided tens of thousands of jobs. They also provided an object lesson in the hazards of industrial development. Coal smoke fouled the air over the valley, and the canals carved out of the wetland were an even larger nuisance. The Milwaukee Sentinel (July 17, 1874) described the state of the south canal:

Certain it is that from some cause that body of water is a river of death, disgusting in the extreme to the sight and fearfully offensive to the olfactories. From its frightfully filthy depths arise boiling springs and a stench so penetrating and all-pervading as to be utterly unbearable.

Rivers were the most visible casualties of urbanization, but Lake Michigan did not escape its share of abuse, and sewage was only the beginning. In the late 1800s, after trying both landfill and incineration, Milwaukee simply towed its solid waste out to the lake and dumped it overboard. “Old Michigan Gets It,” reported the Milwaukee Sentinel (June 9, 1887), describing the first scow’s journey “in a southeasterly direction a distance of several miles, so as to steer clear of the water works intake.” The Daily News (Oct. 27, 1891) declared that Milwaukee was lucky: “She has the broad bosom of Lake Michigan upon which the foul substances may be permitted to escape with no danger of ever being heard from again.” That confidence was sorely misplaced. Jones Island fishing crews objected strenuously when they pulled up trash instead of trout. “Dogs, cats and rats, turkey legs and turkey skeletons, cans and all sorts of things got into the nets and tore them to pieces,” reported the Milwaukee Sentinel (Jan. 8, 1892). One fisherman, Fred Kuehn, had $500 worth of nets completely ruined.

A more serious threat originated hundreds of miles to the east. Since the first canal bypassing Niagara Falls opened in 1829, exotic species had been gradually making themselves at home in the Great Lakes. The first immigrant of real significance was the smelt, which reached Lake Michigan in 1923 and soon became a favorite of dip-netters who gathered on the shores every spring. Other visitors were distinctly unwelcome, particularly the sea lamprey, which arrived in 1936 and decimated the native lake trout population. When alewives reached the lake in 1949, there was no fish at the top of the food chain to control them, and their population spiraled out of control. The introduction of coho salmon in 1966 helped to restore the balance, but the price was an ecosystem dominated by an introduced predator and an introduced prey. More pervasive have been the mussels, first zebra and then quagga, that arrived in the ballast water of ocean-going ships and in time colonized virtually the entire lake floor.[19]

The mussels will not be leaving any time soon, but there is no doubt that the most recent chapter in the story of Milwaukee water is more hopeful than those that preceded it. Tighter regulation, particularly in the wake of the Clean Water Act of 1972, and growing public awareness have spawned a sea change in the condition of local waterways. A two-mile RiverWalk now graces the downtown portion of Milwaukee’s foundational stream, and expensive condominiums line its banks farther north. The forlorn and nearly forgotten Menomonee Valley has come back to life as a destination for both tourism and clean industry. The downtown lakefront—home of the Milwaukee Art Museum, Discovery World, the lake schooner Denis Sullivan, Lakeshore State Park, and the Summerfest grounds—has become a cultural theme park, and the Water Council is working to make Milwaukee a global hub of water technologies. Water runs through the city’s history like a river, and it will keep flowing into a future that lies eternally around the next bend.

Footnotes [+]

- ^ William C. Alden, Quaternary Geology of Southeastern Wisconsin (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1918), 37-38.

- ^ Charles E. Brown, “Archaeological History of Milwaukee County,” The Wisconsin Archeologist 15, no. 2 (July 1916): 24-25.

- ^ History of Milwaukee Harbor, Wisconsin (Milwaukee: U.S. Engineer Office, 1937), 20; Milwaukee City Directory for 1857 & 1858 (Milwaukee: Erving, Burdick & Co., 1857), xi.

- ^ Milwaukee Sentinel, April 5, 1848.

- ^ Bayrd Still, Milwaukee: The History of a City (Madison, WI: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1948), 181.

- ^ James S. Buck, Pioneer History of Milwaukee, vol. 1, revised (Milwaukee: Swain & Tate, 1890), 221-222.

- ^ James S. Buck, Milwaukee under the Charter, vol. 3 (Milwaukee: Symes, Swain & Co., 1884), 203; Milwaukee City Directory for 1857 & 1858 (Milwaukee: Erving, Burdick & Co., 1857), xv.

- ^ Tom Tolan, Riverwest: A Community History (Milwaukee: COA Youth and Family Centers, 2003), 9-14.

- ^ Harry Anderson, “Recreation, Entertainment, and Open Space,” in Trading Post to Metropolis: Milwaukee County’s First 150 Years, ed. Ralph M. Aderman (Milwaukee: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 1987), 259, 263.

- ^ Park Directory (Milwaukee County Park Commission, 1972), 12, 17, 34.

- ^ Robert Wells, Yesterday’s Milwaukee (Miami, FL: A.E. Seemann Publishing, 1976), 107.

- ^ Baist Property Atlas of the City of Milwaukee (Philadelphia, PA: C.W. Baist, 1898), plan 14.

- ^ Ruth Kriehn, The Fisherfolk of Jones Island (Milwaukee: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 1988), 11-15, 35.

- ^ Milwaukee Journal, September 14, 1895; Evening Wisconsin, May 28, 1896; Kriehn, The Fisherfolk of Jones Island, 105-106; Milwaukee Journal, December 14, 1943, and May 24, 1944.

- ^ Elmer W. Becker, A Century of Milwaukee Water (Milwaukee: Milwaukee Water Works, 1974), 4-8, 107.

- ^ Harper’s Monthly Magazine, April 1881.

- ^ Milwaukee Sentinel, Feb. 28, 1916.

- ^ Still, Milwaukee, 457-458.

- ^ Prof. John S. Janssen, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee School of Freshwater Science, “The Marination of the Great Lakes,” presentation at Riveredge Nature Center, Newburg, WI, February 21, 2012.

For Further Reading

Becker, Elmer W. A Century of Milwaukee Water. Milwaukee: Milwaukee Water Works, 1974.

Egan, Dan. The Death and Life of the Great Lakes. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company, 2017.

Foss-Mollan, Kate. Hard Water: Politics and Water Supply in Milwaukee, 1870-1995. West Lafayette, IN: Purdue University Press, 2001.

Gurda, John. Milwaukee: A City Built on Water. Madison, WI: Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 2018.

Gurda, John. Milwaukee: A City Built on Water. Television documentary. Madison, WI: WisconsinEye Public Affairs Network in collaboration with Milwaukee Public Television, 2015. Streams at http://www.mptv.org/video/watch/?id=16590.

History of Milwaukee Harbor, Wisconsin. Milwaukee: U.S. Engineer Office, 1937.

The Milwaukee River: An Inventory of Its Problems, An Appraisal of Its Potentials. Milwaukee: City of Milwaukee, 1968.

Wisconsin Marine Historical Society. Maritime Milwaukee. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing Co., 2011.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.