Fish have long been an important part of Milwaukee’s diet and culture, perhaps most notably in the “Friday night fish fry.” The city’s commercial fishing industry expanded to meet the needs of local customers but never developed larger markets as did peers in other parts of the Great Lakes.[1]

Native American communities subsisted on fish from Lake Michigan and area rivers for thousands of years prior to the establishment of Milwaukee. The city’s earliest American settlers followed suit.[2] Pioneer fishermen established docks and shanties along the shores of the Milwaukee River and on what became Jones Island, forming a vibrant fishing industry here by the 1860s.[3]

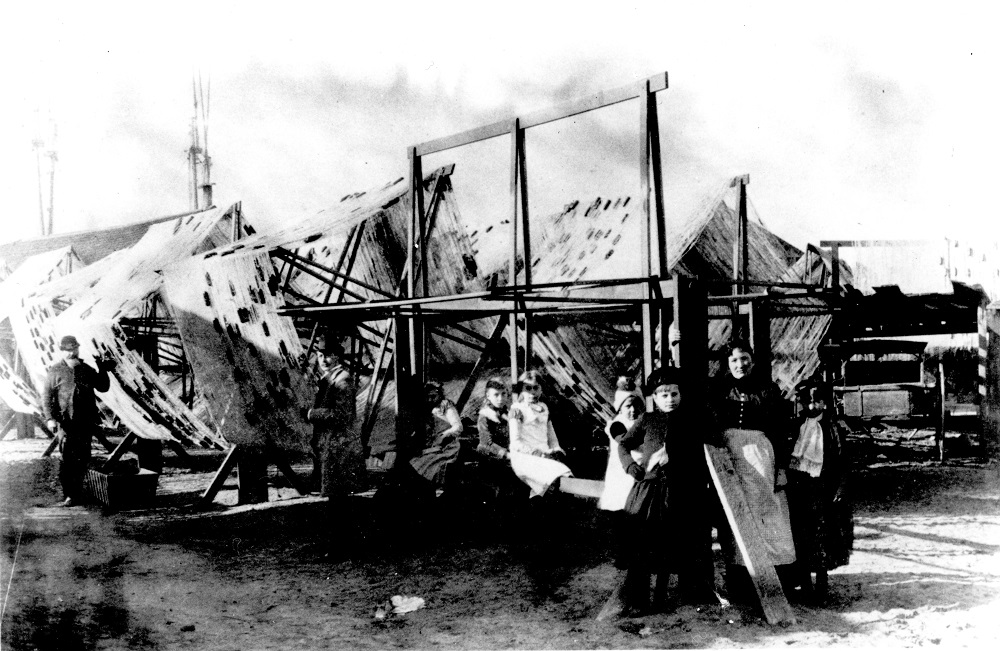

The industry flourished as a dynamic socio-economic community after Kashubian Poles and Pomeranian Germans settled Jones Island in the 1870s. Coming from established fishing communities in Eastern Europe, these Polish and German immigrants created a makeshift fishing village on the newly created island, adapting traditional fishing methods to their new environment.[4] Port Washington also developed into an important area fishing center in the mid-nineteenth century as pioneer fishermen sought new fishing grounds along the western shores of Lake Michigan.[5]

Commercial fishing developed chiefly as a family business in Milwaukee and changed very little as independent, family-based firms operated into the twenty-first century.[6] While men worked “catches” with the help of their sons, women and daughters fashioned and repaired nets, helped process the catch, and managed the home.[7] Extended family units spread out costs of building and maintaining shanties, boats, and other equipment. They also provided support following a disastrous loss of life or assets within the fishing community.[8]

Fishing was difficult and dangerous work. Nets, lines, and boats were always vulnerable to damage, and violent storms and waves were hazardous to crews’ lives.[9] The industry was also subject to seasonal fluctuations in weather, lake conditions, and fish populations. Many fishermen and their family members worked in nearby industries, like the Bay View rolling mills, to supplement their income.[10] Fishermen who upgraded to larger steam tugs in the early twentieth century found alternative kinds of work during downtimes.[11]

Lake Michigan’s seemingly limitless populations of lake trout, whitefish, lake herring (chubs), perch, and sturgeon produced growing yields of fish into the early twentieth century—nearly 2 million pounds of fish a year by the 1910s.[12] Fishermen washed, iced, or smoked their catches before selling them to local fish peddlers and wholesalers.[13] Milwaukee and surrounding communities consumed most of this fish, especially during Lent; Chicago absorbed any surplus.[14]

Substantial problems emerged that prompted the industry’s decline over the course of the twentieth century. After decades of talk about displacement, in the 1920s the city began to evict Jones Island residents to provide for the construction of a new wastewater treatment plant and updated harbor facilities, thereby scattering the island’s fishing operations to less ideal locations along the city’s rivers further inland.[15] Moreover, decades of industrial and human pollution, overfishing, and invasive species like lamprey eels, alewives, smelt, mussels, and Asian carp gradually depleted Lake Michigan’s rich populations of commercial fish.[16] State and federal conservation agents increasingly regulated fish harvests and arrested Milwaukee fishermen who violated legal seasonal limits.[17] Milwaukee’s fishing industry faded away as fishermen found local waters less profitable. The market’s needs were increasingly met with fish flown in from more productive locations.[18] Milwaukee’s last commercial fishing operation left the city in 2011.[19]

Footnotes [+]

- ^ Chicago, Buffalo, Detroit, Toledo, Sandusky, Huron, and Cleveland were much larger centers of the Great Lakes commercial fishing industry. Margaret Beattie Bogue, Fishing the Great Lakes: An Environmental History, 1783-1933 (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 2001), 37.

- ^ Bogue, Fishing the Great Lakes, 5-9; John Gurda, The Making of Milwaukee (Milwaukee: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 1999), 6-9; Ruth Kriehn, The Fisherfolk of Jones Island (Milwaukee: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 1988), 1-2.

- ^ Kriehn, The Fisherfolk of Jones Island, 4, 8.

- ^ Gurda, The Making of Milwaukee, 135; Kriehn, The Fisherfolk of Jones Island, 12-15, 20-21, 24-27.

- ^ Richard D. Smith and Linda M. Nenn, Out of the Past: Recollections of Port Washington’s Maritime History, vol. 3, The Fishermen, rev. ed. (Port Washington, WI: LMN Publications, 1999); Kriehn, The Fisherfolk of Jones Island, 8-10, 37; Robert C. Nesbit, History of Wisconsin: Urbanization & Industrialization 1873-1893, vol. 3 (Madison, WI: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1985), 185; Donna Wirth, “Family Achievement: Commercial Fishing Led to Restaurants,” Milwaukee Journal, August 16, 1967, sec. 5, p. 8, 24.

- ^ Bogue, Fishing the Great Lakes, 75; Kriehn, The Fisherfolk of Jones Island, 31-33, 38-39; “Let’s Go Fishing on Lake Michigan,” Milwaukee Journal, May 29, 1938, Roll 406, Milwaukee Features Clipping File, Milwaukee County Historical Society; Dean Jensen, “Ban on Commercial Trout Has Anglers at End of Line,” Milwaukee Sentinel, July 6, 1974, sec. 1, p. 5, 12; Dan Egan, “‘The Lake Left Me. It’s Gone,’” JSOnline, August 13, 2011.

- ^ Bogue, Fishing the Great Lakes,75-76.

- ^ Kriehn, The Fisherfolk of Jones Island, 13, 21.

- ^ Kriehn, The Fisherfolk of Jones Island,, 32, 37, 47-68.

- ^ Bogue, Fishing the Great Lakes, 32-33; Kriehn, The Fisherfolk of Jones Island, 15; “Let’s Go Fishing on Lake Michigan.”

- ^ Kriehn, The Fisherfolk of Jones Island, 34.

- ^ Bogue, Fishing the Great Lakes, 149; Kriehn, The Fisherfolk of Jones Island, 35, 41.

- ^ Kriehn, The Fisherfolk of Jones Island,, 34, 38-42.

- ^ Kriehn, The Fisherfolk of Jones Island,, 34, 41-42; “500 Tons Annual Catch of Milwaukee Fishermen,” Milwaukee Sentinel, December 7, 1930, sec. C, p. 6.

- ^ Kriehn, The Fisherfolk of Jones Island, 21, 36, 39, 46; Gurda, The Making of Milwaukee, 262-263; “Let’s Go Fishing on Lake Michigan.”

- ^ Bogue, Fishing the Great Lakes, 141; Nesbit, History of Wisconsin, 3:258; Kriehn, The Fisherfolk of Jones Island, 37, 45-46; “Governor Goes Fishing,” Milwaukee Journal, February 10, 1940, sec. 1, p. 1; “Outlook for Revived Lakes Fishing Improved,” Milwaukee Journal, January 12, 1965, sec. 1, p. 1.

- ^ Kriehn, The Fisherfolk of Jones Island, 34-35; Jensen, “Ban on Commercial Trout Has Anglers at End of Line,” 12.

- ^ “Jaunts with Jamie: Lake Fishing a Rugged Job,” Milwaukee Sentinel, March 24, 1962, Roll 406, Milwaukee Features Clipping File, Milwaukee County Historical Society.

- ^ Egan, “‘The Lake Left Me. It’s Gone.’”

For Further Reading

Bogue, Margaret Beattie. Fishing the Great Lakes: An Environmental History, 1783-1933. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 2000.

Kriehn, Ruth. The Fisherfolk of Jones Island. Milwaukee: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 1988.

Smith, Richard D., and Linda M. Nenn. Out of the Past: Recollections of Port Washington’s Maritime History. Vol. 3, The Fishermen, Rev. ed. Port Washington, WI: LMN Publications, 1999.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.