Throughout the city’s history, Milwaukeeans have engaged in outdoor recreational activities in pursuit of fitness, entertainment, community development, and other benefits. Outdoor recreation varies from individual to collective in scale, and from relaxing to active in character. Unlike indoor varieties, outdoor recreation changes with the seasons, and Milwaukeeans commonly engaged in both warm and cold weather activities. Different groups formed to organize competitive or cooperative outdoor activities, improve recreational infrastructure, foster community relationships, and promote the wellness of residents.

Recreation Time

Many accounts of Milwaukee’s early days refer to the experiences of settlers hunting, fishing, foraging, and engaging in other activities we might now consider recreational. According to local chronicler John G. Gregory, for instance, the pioneer financier Alexander Mitchell “frequently turned the key in the door of his bank at the noon hour and went for a stroll with his gun in the neighborhood of Marshall Street and what is now Juneau Avenue,” which “had not [yet] been built upon or cleared of trees.”[1] Foragers found plentiful blackberry and raspberry bushes in clearings near the North Avenue dam, often returning home with buckets full of berries in the summer.[2] Although Milwaukee’s early settlers fondly remembered their time hunting, fishing, and foraging in the area, these endeavors were often deeply ingrained into the practices of daily life and contributed to the survival of the frontier community’s residents.

Nineteenth-century notions of recreation changed with labor practices, namely the division of time between work and leisure, in industrializing American cities like Milwaukee. While manufacturers increasingly relied on labor for mass production, workers demanded and eventually won shortened work days and weeks (along with increased wages) that accommodated leisure pursuits. As Milwaukee joined the Eight-Hour Movement’s call for a shortened work day, organizers argued that such a move would allow the city’s workers “eight hours for rest, and eight hours for what we will.”[3] Some industrialists also understood that offering more leisure opportunities could boost the happiness and health, and thus the productivity, of their workers. This kind of “welfare capitalism” was popular with some large Milwaukee manufacturers in the early twentieth century.[4]

At the same time, employers and social reformers expressed concern that Milwaukee’s working classes often misused their leisure time when left to their own devices. This motivated endeavors to shape leisure practices, such as efforts by employers to curb “Blue Mondays” (when workers proved less productive after drinking on the weekend), and the “Safe and Sane” campaign of middle-class Progressives to stem the fireworks and firearm injuries that occurred on Independence Day. As reformers instituted greater limitations on child labor, they also feared that, without proper guidance, the resulting free time might lead Milwaukee’s youth to “lawlessness, immorality, and radicalism.” Organizations like the Children’s Betterment League of Milwaukee worked to institute safe, wholesome, and reliable places to play—playgrounds, social centers, youth recreational programming—in their efforts to secure an “ideal childhood” for the city’s youth.[5]

Recreation Spaces

Milwaukeeans historically pursued outdoor recreation anywhere it was practical to do so. This was particularly true of the city’s youth. The most accessible leisure spaces were often the yards, sidewalks, streets, alleyways, and empty lots of Milwaukee neighborhoods. One resident recalled roller-skating around her East Side block as a child in the early twentieth century. She especially enjoyed the smooth stretch of sidewalk in front of Mayor David Rose’s house, where “elderly ladies sat in rocking chairs on the front porch, fanning themselves on a hot summer day, and keeping an eagle eye on the skaters.”[6] Streets were especially important playgrounds for children in densely packed neighborhoods like Brady Street, where there was very little yard space.[7]

Milwaukee’s waterways were also important sites for recreation. Publisher William George Bruce explained that the docks and yards along the Milwaukee River near his late-nineteenth century childhood home were popular places for neighborhood youth to play, fish, and swim. “The lumberyards were especially adapted for hide and seek games,” Bruce recalled, adding that their wood piles were a handy source for projectiles and floatation devices for children playing in and around the river.[8] Bruce also recounted how young boys rowed along the river in yawls they acquired from docked schooners. “If they were pursued by the crew,” he noted, “they landed on the opposite side of the river and scampered off to safety.”[9]

The pastoral and wooded areas on the fringes of Milwaukee and beyond were also popular leisure spots, away from the noise, crowds, and pollution of the city. In 1888, the Milwaukee Sentinel reported that several small groups celebrated Independence Day with picnics “along the railroads and up the river” outside of the city.[10] Streetcar, train, and boat lines advertised weekend trips to parks and resorts in surrounding communities.[11] Parties of sportsmen also ventured to public and private grounds outside of the city in pursuit of game. Deer hunting season remains a cherished institution among many Milwaukee area residents who trek into the woodlands surrounding the city and Up North every autumn.[12]

Demands for more accessible outdoor recreation spaces increased as the frontier city grew through the mid-to-late nineteenth century. While the city maintained a few public squares, private interests largely fulfilled Milwaukee’s early recreational needs. Immigrant entrepreneurs, for instance, established lavish beer gardens as familiar cultural institutions for the large numbers of Germans who settled in the city. Featuring ornamental plantings, animal menageries, games, and large open spaces for a variety of activities, these gardens were important recreational spaces “where the German citizenry danced at night, listened to open air concerts, and bought cakes, coffee, and beer.”[13] Later, private amusement parks offered thrilling rides, midway games, stunt exhibitions, and other popular American mass cultural amusements to the second and third generations of Milwaukee’s working-class immigrant communities.[14] Private outdoor recreation facilities remain important institutions in the metropolitan area to this day, including country club golf courses, tennis courts, polo grounds, soccer fields, and other places often intended to serve more affluent residents.

Milwaukee’s celebrated public park system emerged through the efforts of late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century reformers to improve urban living conditions and shape the leisure practices of the city’s working class. Public parks, many progressives believed, could help remedy the environmental challenges of urban industrialization by serving as “lungs” for the city, as well as alleviate social conflict by cultivating peaceful settings.[15] Additionally, socialists understood that properly administered public parks could offer cheaper alternatives to commercial amusement spaces for the city’s working class, featuring attractions like zoos, baseball diamonds, golf courses, tennis courts, boating lagoons, swimming and picnic facilities, and concert pavilions.[16] Progressive and socialist reformers also established playgrounds and social centers—typically attached to neighborhood schools—to provide Milwaukee children with wholesome places to play, as well as educational and civic programming.[17] Additionally, groups like the Young Men’s Christian Association, Children’s Outing Association, Boy Scouts, and various ethnic organizations established camps in the areas surrounding Milwaukee for children to engage in recreational activities that instilled the group’s traditions and values. In an extreme case, the German-American Volksbund (or “the Bund”) established a youth summer camp, Camp Hindenburg, along the Milwaukee River in Grafton in 1937 to instill Nazi ideals in Milwaukee’s German community. Anti-Nazis in the city’s German-American Federation successfully limited the Bund’s influence and took over the camp’s operation in 1939. They renamed it after Carl Schurz, the famous Milwaukee abolitionist and founder of the German-American Turner movement.[18]

In the early twentieth century, a growing statewide conservation movement sought to preserve large portions of the natural landscape outside of the city for public recreation. These state parks would “refresh and strengthen and renew tired people,” one proponent argued, “to fit them for the common round of daily life.”[19] In the 1920s, state conservationists started acquiring and preserving portions of the Kettle Moraine—a band of rolling hills, lakes, and marshes formed by Ice Age glaciers stretching from Walworth to Sheboygan counties to the west and north of Milwaukee. With the help of the New Deal’s Civilian Conservation Corps and Works Progress Administration programs, these efforts produced the Kettle Moraine State Forest in the late 1930s and 1940s, featuring a scenic drive, numerous hiking and ski trails, camp sites, hunting grounds, and picnic spots at state parks, including Lapham Peak outside of Delafield.[20] In the late 1950s, Milwaukee conservationist Raymond Zillmer launched an effort to establish a national trail through the Kettle Moraine that would highlight the region’s glacial history and agricultural heritage. The Ice Age Trail was officially designated a National Scenic Trail in 1980.[21] Conservationist groups have also established a few privately-operated preserves in the Milwaukee area since the 1960s, including the Schlitz Audubon Nature Center in Bayside, the Riveredge Nature Center in Saukville, and the Urban Ecology Center in Milwaukee. In addition to protecting and restoring the area’s landscape and wildlife and fostering environmental education, these facilities offer a number of nature trails for hikers, skiers, and snowshoers.[22]

Similarly, groups of historic preservationists worked to save pieces of Wisconsin’s nineteenth century ethnic infrastructure that had increasingly deteriorated and disappeared through the twentieth century. Their efforts coincided with the renewed interest of many Americans in their ethnic heritage and a growing desire for history-based tourism that emerged in the decades following the Second World War. In the late 1960s, preservationists partnered with the State Historical Society of Wisconsin to acquire, relocate, and preserve several historic buildings for an open-air history and ethnic heritage museum in the Kettle Moraine outside of Eagle. Officially opened for the national bicentennial in 1976, Old World Wisconsin welcomes tens of thousands of visitors every year.[23]

Suburbanization reshaped the landscape of outdoor recreation in Milwaukee in the mid-to-late twentieth century. White middle-class Milwaukeeans joined their counterparts in cities throughout the United States in pursuit of more spacious homesteads in communities on the outskirts of the city. In the process, they relocated many of their regular recreational activities—like picnics, games, and swimming—from city parks to their own backyards. By the 1980s, suburbanization and an accompanying reduction in industrial jobs greatly reduced the revenue capacity and political will for the City and County governments to continue to maintain their large array of recreational facilities, prompting the deterioration and closure of some locations—particularly in non-white inner-city neighborhoods.[24]

A recent “back to the city” movement has generated a renaissance in urban recreational spaces in Milwaukee. Developments like the Oak Leaf and Hank Aaron trails, RiverWalk, and Swing Park have effectively repurposed old industrial sites and railroad beds as recreational spaces. Moreover, the Milwaukee County Parks Department has also partnered with local breweries and restaurants to establish beer gardens reminiscent of those from the nineteenth century city in select park locations.[25]

Warm Weather Recreation

As the city thaws from the winter cold and ice, and daylight hours extend later into the evening, Milwaukee residents and visitors flocked to area parks, trails, rivers, lakes, ballparks, and other outdoor spaces for an array of recreational activities. Perhaps the most common of these warm weather pursuits is walking. While certainly a fundamental mode of transportation, walking has been an important form of exercise and relaxation to many Milwaukeeans since the city’s origins. Much like Alexander Mitchell generations before him, William George Bruce recalled taking regular evening strolls through the Polish immigrant neighborhoods around his Walker’s Point home in the early twentieth century.[26] Stewards of beer gardens, parks, and trails historically cultivated paths specifically for area residents to walk and hike through gardens and nature preserves. Running is also a common form of warm weather recreation, using many of the same streets and trails as walkers. Running had long been a fixture of organized track sports in area schools. By the end of the twentieth century, however, it had become a popular form of individual exercise. Milwaukee joined other American cities in organizing running clubs, like the Badgerland Striders, and races, like the Lakefront Marathon.

Cycling is another popular warm weather pursuit, and Milwaukee was a key site in the sport’s early development. Joshua G. Towne made the first recorded bicycle ride through the streets of Milwaukee on a wood and iron “velocipede” in 1869.[27] By the end of the nineteenth century, cycling had become an exceptionally popular sport in the city—particularly among white middle- and upper-class men. Organizations like the Milwaukee Cycling Club and the Milwaukee Wheelmen emerged in the 1880s to advocate for the sport’s growth, organize races and rides, and improve cycling infrastructure and safety.[28] Groups like the Cream City Cycle Club, the Bay View Bicycle Club, and Cadence continue to promote cycling on Milwaukee area roads and trails.[29]

Warm weather also drew Milwaukeeans to water in pursuit of cool places to relax, socialize, and play. Swimming was among the most common of these water activities, and area residents have bathed in area lakes, rivers, and pools since the city’s earliest days.[30] The Milwaukee River was home to several public bathhouses and private swimming schools in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Patchkowsky’s swimming school, for instance, was located just north of the modern-day Pleasant Street bridge in the 1860s. Pollution concerns prompted bathers to seek safer spots above the North Avenue Dam like Rohn’s, Whittaker’s, and Bechstein’s swimming schools and the Gordon Park bathhouse in the late nineteenth century, and swimming pools in public parks by the mid-twentieth century.[31] Lake Michigan has also drawn bathers since the city’s origins. Developed as part of efforts to stem erosion and improve public access to the lake in the 1900s through 1920s, Bradford and McKinley beaches remain popular spots for Milwaukeeans to swim, tan, play volleyball, and catch a cool lake breeze.[32]

“There have always been enthusiastic amateur sailors in Milwaukee,” one city historian noted, and area waterways remain important places for recreational boating.[33] Sailors and motorboaters regularly set out from marinas and private docks on Lake Michigan and other area lakes for pleasure and sport. Established in 1871, members of the Milwaukee Yacht Club have set sail from what is now the McKinley Marina since 1896—the same year a yacht club was founded on Pewaukee Lake.[34] A group of pleasure boaters established the Port Washington Yacht Club in 1956, and subsequently worked to improve that city’s harbor and bathing facilities.[35] In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, Milwaukeeans rented rowboats on hot summer days to paddle between various beer gardens and parks along the Milwaukee River.[36] Crews of amateur rowers from organizations like the Milwaukee Rowing Club (established in 1894) have also trained and competed on the Milwaukee River since the mid-to-late nineteenth century. Clean-up and redevelopment efforts have drawn many recreational boaters back to the city’s rivers since the 1960s. Motorboaters troll between the lake and docks at new riverside condos, restaurants, and bars on summer weekends. New launches at Milwaukee parks and trails have also made the city’s waterways popular for canoers and kayakers.

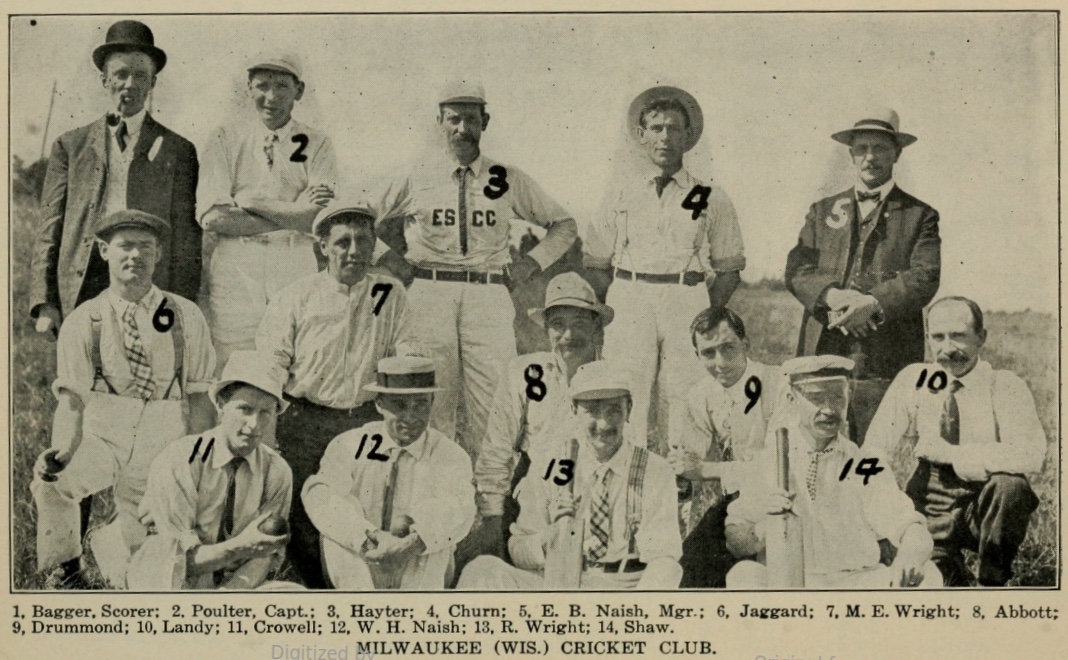

As the formation of running, cycling, and rowing clubs suggests, warm weather recreation was often organized. Ethnic groups, civic associations, labor unions, and municipal agencies coordinated summer festivals and picnics throughout the city’s history to celebrate holidays, reinforce community relationships, and promote economic development. In addition to food, drink, music, speakers, and demonstrations, these events often included an array of races and games for participants to engage in friendly competition.[37] Various organizations have also fielded sports teams since the city’s charter. Yankee-Yorkers first brought baseball along with its English cousin, cricket, to the city before the Civil War, and Milwaukeeans have played amateur league and pick-up games in area parks, playgrounds, and sandlots ever since.[38] Soccer can trace its origins in Milwaukee to amateur clubs formed in the late-nineteenth and early twentieth century.[39] Over time, different clubs have similarly formed to play tennis, basketball, lawn bowling, polo, bocce, hurling, and rugby.

Although some enthusiasts persist through the first snowfall, golf is most often played in warmer weather. Played either collectively or individually, golf made its first appearance in Milwaukee in 1894 on a makeshift course laid out in an East Side cow pasture, partly on the current site of the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. Golf is largely considered a game for the affluent, which is certainly true of the private courses and clubs in the Milwaukee area that charge high membership and course fees. However, Milwaukee is also home to a number of public golf courses located in the county park system developed after the turn of the twentieth century to ensure the sport’s accessibility to a wide variety of players.[40] Milwaukee’s public parks have similarly accommodated the increased popularity of disc golf (or frisbee golf) in recent years, developing courses in under-used parts of system parklands.

Cold Weather Recreation

While warm weather often draws the most area residents outdoors, many Milwaukeeans also brave the ice of area lakes, rivers, and outdoor rinks, as well as snow-covered hills and trails for a range of cold weather pursuits. As in warm weather, the most basic forms of cold weather play simply involved building forts, throwing snowballs, and playing games in neighborhood streets and yards. Early settlers raced horse-drawn sleighs through snow-covered streets of the frontier city and a makeshift racetrack on the Milwaukee River south of Cherry Street.[41] Ice skaters of all kinds found plentiful surfaces on the area’s frozen waterways. As one early settler recalled, “I have put on my skates at the corner of Wisconsin and Van Buren streets and skated from there south to the old harbor mouth,” through the marshlands that occupied what is now the Third Ward.[42] Despite his heft, one of the city’s founders, George Walker, was reportedly a “skater of unusual grace.”[43] Scores of Milwaukeeans spent winter evenings and Sunday afternoons skating on the Milwaukee River north of the North Avenue Dam—especially in the area between Riverside and Gordon parks—through the early twentieth century.[44] Ice skaters still enjoy rinks and ponds at Milwaukee area parks, most notably at downtown’s Red Arrow Park.

Those interested in snow-based sports have found numerous outlets in the Milwaukee area, as well. After a fresh snowfall, any open hill is prime for downhill runs in sleds, toboggans, saucers, or inner tubes. Downhill skiers (and later snowboarders) have enjoyed the slopes of private ski hills and members-only ski clubs in the Kettle Moraine north and west of the city since the 1940s and 1950s.[45] Long used as practical means of transportation, Nordic skis and snowshoes had become popular among outdoor enthusiasts in the area by the 1970s and 1980s—encouraged by groups like the Nordic Ski Club of Milwaukee. Since then, many cross-country skiers and snowshoers have enjoyed Milwaukee area hiking trails after a fresh snowfall every winter.[46]

Albeit more limited than in warmer weather, groups of Milwaukeeans pursued organized sports in cold weather, as well. Scottish immigrants established the Milwaukee Curling Club in 1845, first playing on the frozen Milwaukee River before moving to indoor rinks in the early twentieth century.[47] Prior to safety concerns and the destruction of the North Avenue Dam in the 1990s, neighborhood youth also organized pick-up games of hockey on the Milwaukee River and park ponds, often challenging their rivals from other neighborhoods.[48]

Recreational infrastructure, interests, and technology have certainly changed considerably in Milwaukee since the city’s charter. Yet, outdoor recreation remains a vibrant part of daily life in the Milwaukee area as residents and visitors continue to venture out to area yards, parks, trails, waterways, and other outdoor spaces every day to play, relax, and exercise.

Footnotes [+]

- ^ John G. Gregory, History of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, vol. 2 (Chicago: S.J. Clarke, 1931), 1055–56.

- ^ Gregory, History of Milwaukee, 2:1057.

- ^ Roy Rosenzweig, Eight Hours for What We Will: Workers and Leisure in an Industrial City, 1870-1920 (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 1983), 1-5.

- ^ Joseph B. Walzer, “Suds and Solidarity: Outdoor Leisure Spaces and Working Class Identities in Milwaukee, 1880-1925” (Master’s thesis, University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee, 2009), 131-32.

- ^ Daryl Webb, “‘A Great Promise and a Great Threat’: Milwaukee Children in the Great Depression” (Ph.D. diss., Marquette University, 2006), 15-20.

- ^ Eve Benyas, “Memories of Old Milwaukee,” Milwaukee Journal, January 15, 1965, sec. 1, 20; Eve Benyas, “Memories of Old Milwaukee,” Milwaukee Journal, January 15, 1965, sec. 1, 20.

- ^ Frank D. Alioto, Milwaukee’s Brady Street Neighborhood (Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2008), 50-51, 59.

- ^ William George Bruce, “Old Milwaukee,” Wisconsin Magazine of History 27, no. 3 (March 1944): 307.

- ^ Bruce, “Old Milwaukee,” 307-8.

- ^ “In the Open Air,” Milwaukee Sentinel, July 5, 1888, sec. 6, p. 1.

- ^ Joseph B. Walzer, “Suds and Solidarity”, 21.

- ^ Robert C. Willging, On the Hunt: The History of Deer Hunting in Wisconsin (Madison, WI: Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 2008), 57-61.

- ^ Walzer, “Suds and Solidarity,” 16-21; Illustrated Historical Atlas of Milwaukee County, Wisconsin (Chicago, IL: H. Belden, 1876), 43, 89; Harry H. Anderson, “Recreation, Entertainment, and Open Space: Park Traditions in Milwaukee County,” in Trading Post to Metropolis: Milwaukee County’s First 150 Years, ed. Ralph M. Aderman (Milwaukee: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 1987), 258; Bayrd Still, Milwaukee: The History of a City (Madison, WI: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1958), 79.

- ^ Anderson, “Recreation, Entertainment, and Open Space,” 261; Walzer, “Suds and Solidarity, ” 141-42.

- ^ Rosenzweig, Eight Hours for What We Will, 128-130, 136-152.

- ^ Anderson, “Recreation, Entertainment, and Open Space,” 281-292.

- ^ Elizabeth Jozwiak, “Politics in Play: Socialism, Free Speech, and Social Centers in Milwaukee,” Wisconsin Magazine of History 86, no. 3 (Spring 2003): 12-15; Victor Greene, “Dealing with Diversity: Milwaukee’s Multiethnic Festivals and Urban Identity, 1840-1940,” Journal of Urban History 31, no. 6 (September 2005): 828-829.

- ^ Dieter Berninger, “Milwaukee’s German-American Community and the Nazi Challenge of the 1930s,” Wisconsin Magazine of History 71, no. 2 (Winter 1987-1988): 121-139.

- ^ John Nolen, State Parks for Wisconsin ([Wisconsin]: State Park Board, 1909), 22

- ^ C.L. Harrington, “The Story of the Kettle Moraine State Forest,” Wisconsin Magazine of History 37, no. 3 (Spring 1954): 143-145; Sarah Mittelfehldt, “The Origins of Wisconsin’s Ice Age Trail: Ray Zillmer’s Path to Protect the Past,” Wisconsin Magazine of History 90, no. 3 (Spring 2007): 4.

- ^ Mittelfehldt, “The Origins of Wisconsin’s Ice Age Trail,” 8, 13.

- ^ “Our History in Milwaukee,” Schlitz Audubon Nature Center website, accessed December 5, 2018, https://www.schlitzaudubon.org/about-us/our-history/; “Riveredge History,” Riveredge Nature Center website, accessed December 5, 2018; “History,” Urban Ecology Center website, accessed December 5, 2018.

- ^ John D. Krugler, Creating Old World Wisconsin: The Struggle to Build an Outdoor History Museum of Ethnic Architecture (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 2013), 3-13; Laurie Jerin, Thomas M. Phan, and Heather A. Priess, “An Analysis of the Operation and Funding Model of Wisconsin Historic Sites” (Madison, WI: Robert M. La Follette School of Public Affairs, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 2001), last accessed April 8, 2019.

- ^ Anderson, “Recreation, Entertainment, and Open Space,” 315-318.

- ^ Steve Schultze, “Milwaukee County to Solicit Bids for Beer Gardens in Some Parks,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, January 11, 2012; Sue Black, interview, WTMJ News Team, “Milwaukee County Parks Looking to Bring Back Beer Gardens,” Today’s TMJ4, last updated January 10, 2012, http://www.todaystmj4.com/news/local/137056693.html.

- ^ William George Bruce, History of Milwaukee, City and County, vol. 1 (Milwaukee: S.J. Clarke, 1922), 183-185.

- ^ Jesse J. Gant and Nicholas J. Hoffman, Wheel Fever: How Wisconsin Became a Great Bicycling State (Madison, WI: Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 2013), 1.

- ^ Gant and Hoffman, Wheel Fever, 43-76.

- ^ “About CCCC,” Cream City Cycle Club, accessed November 16, 2018; “About Us,” Bay View Bicycle Club, accessed November 16, 2018; “About Us,” Cadence: A Women’s Cycling Group, accessed November 16, 2018.

- ^ Bruce, History of Milwaukee, 1:119; Gregory, History of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, 2:1069-1070.

- ^ Gregory, History of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, 2:1066.

- ^ Carl Baehr, “Lincoln Memorial Dr. Was Under Water,” Urban Milwaukee, May 20, 2016, last accessed April 8, 2019; Frank D. Alioto, Milwaukee’s Brady Street Neighborhood (Charleston, SC: Arcadia, 2008), 76.

- ^ Gregory, History of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, 2:1069.

- ^ “Club History,” Milwaukee Yacht Club, accessed December 3, 2018; “About Us,” Pewaukee Yacht Club, accessed December 3, 2018.

- ^ “History,” Port Washington Yacht Club, accessed December 3, 2018.

- ^ Alioto, Brady Street, 76.

- ^ Walzer, “Suds and Solidarity,” passim.

- ^ Dennis Pajot, The Rise of Milwaukee Baseball: The Cream City from Midwestern Outpost to the Major Leagues, 1859-1901 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2009), 3-6; Brian A. Podoll, The Minor League Milwaukee Brewers, 1859-1952 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2003), 3-5.

- ^ Eric Anderson, “Waukesha: Birthplace of U.S. Soccer?,” accessed November 26, 2018.

- ^ John Gurda, Cream City Chronicles: Stories of Milwaukee’s Past (Madison, WI: Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 2007), 193-195; Anderson, “Recreation, Entertainment, and Open Space,” 279, 283-284, 287, 292.

- ^ Gregory, History of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, 2:1059; Gurda, Cream City Chronicles, 272.

- ^ Gurda, Cream City Chronicles, 272.

- ^ John Gurda, The Making of Milwaukee, 37.

- ^ Gregory, History of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, 2:1066; John Gurda, “Our Ancestors Knew How to Unplug in Winter and Enjoy a Good Milwaukee River Skate,” JSOnline, February 2, 2018, last accessed April 8, 2019; Laurie Muench Albano, Milwaukee County Parks (Charleston, SC: Arcadia, 2007), 33.

- ^ Rick Barrett, “Little Switzerland Resort to Reopen,” JSOnline, November 28, 2012, last accessed April 8, 2019; Bill Glauber, “Milwaukee Area Private Ski Clubs Thrive on Snow, Family, and History,” JSOnline, February 8, 2017, last accessed April 8, 2019.

- ^ “Nordic History,” Nordic Ski Club of Milwaukee, accessed November 29, 2018.

- ^ Gregory, History of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, 2:1068-69; “History,” Milwaukee Curling Club, accessed November 29, 2018.

- ^ Gurda, “Our Ancestors Knew How to Unplug in Winter and Enjoy a Good Milwaukee River Skate.”

For Further Reading

Anderson, Harry H. “Recreation, Entertainment, and Open Space: Park Traditions in Milwaukee County.” In Trading Post to Metropolis: Milwaukee County’s First 150 Years, edited by Ralph M. Aderman, 255-323. Milwaukee: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 1987.

Gant, Jesse J., and Nicholas J. Hoffman. Wheel Fever: How Wisconsin Became a Great Bicycling State. Madison, WI: Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 2013.

Greene, Victor. “Dealing with Diversity: Milwaukee’s Multiethnic Festivals and Urban Identity, 1840-1940.” Journal of Urban History 31, no. 6 (September 2005): 820-849.

Harrington, C.L. “The Story of the Kettle Moraine State Forest.” Wisconsin Magazine of History 37, no. 3 (Spring 1954): 143-145.

Jozwiak, Elizabeth. “Politics in Play: Socialism, Free Speech, and Social Centers in Milwaukee.” Wisconsin Magazine of History 86, no. 3 (Spring 2003): 10-21.

Krugler, John D. Creating Old World Wisconsin: The Struggle to Build an Outdoor History Museum of Ethnic Architecture. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 2013.

Mittelfehldt, Sarah. “The Origins of Wisconsin’s Ice Age Trail: Ray Zillmer’s Path to Protect the Past.” Wisconsin Magazine of History 90, no. 3 (Spring 2007): 2-14.

Pajot, Dennis. The Rise of Milwaukee Baseball: The Cream City from Midwestern Outpost to the Major Leagues, 1859-1901. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2009.

Walzer, Joseph B. “Suds and Solidarity: Outdoor Leisure Spaces and Working Class Identities in Milwaukee, 1880-1925.” Master’s thesis, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2009.

Webb, Daryl. “‘A Great Promise and a Great Threat’: Milwaukee Children in the Great Depression.” Ph.D. diss., Marquette University, 2006.

Willging, Robert C. On the Hunt: The History of Deer Hunting in Wisconsin. Madison, WI: Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 2008.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.