During most of the twentieth century, the Milwaukee Public Schools (MPS) fashioned a record of accomplishments of which most Milwaukeeans were proud. Over the last third of the century, demographic and economic changes produced daunting problems that weakened public trust and resulted in an educational landscape quite different from that of 1950.

Creating a Public School System, 1846 to 1914

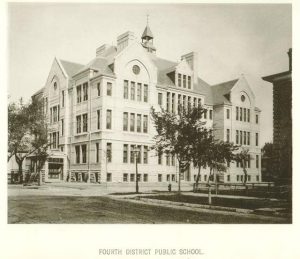

The Milwaukee Public school system was created in 1846. By 1878 there were fourteen (mostly) 1-8 schools and one high school, East Division. The first kindergarten opened a bit later.

Although the state had ultimate authority over public schools, the Milwaukee Board of School Commissioners and its appointed superintendent made most MPS decisions. The first superintendent was Rufus King, chosen in 1859. Throughout most of the nineteenth century, the Milwaukee Common Council selected board members. Each ward had considerable influence over employee hiring and school administration for schools within its boundaries. Starting in 1909, the fifteen board members were elected at large, a move that shifted decision-making from wards to educational professionals in the central office. Property taxes remained the main source of public school revenue.

During much of the nineteenth century, a majority of Milwaukee youth did not get schooling beyond the sixth grade, as many immigrant families sent their children early to work, apprentice programs, and domestic service. Because there were many Catholic, Lutheran, and other parents who wished to keep their European languages alive, the city developed a strong tradition of parochial schools.[1] Public school classes were typically large: forty-to-sixty pupils were common.[2] Students had to purchase their books, although charities subsidized the indigent. The teaching staff was three-fourths female, but males were on average paid more; married females were generally refused employment.[3] Later, when the Milwaukee Teachers Association was formed, teachers sought at least some voice in educational policy-making.

As the nineteenth century progressed, MPS became more centralized and professionalized as the board and superintendent’s office asserted more control over curriculum, textbook selection, and teacher and principal qualifications. As high school enrollments gradually grew, the curriculum reflected student diversity, with classical (college preparation), commercial, and manual training tracks all available. In 1907 Boys Technical and Trade High School became part of MPS at the same time that an increasing emphasis upon manual training in the upper grades reflected the city’s heavy dependence on industrial production. In the later 1800s, schools for the deaf and blind were established, as well as classes for those with learning disabilities. Inter-scholastic athletic competition began in the late 1800s.

These advances coexisted with some contention. The use of corporal punishment and phonics versus sight word approaches in the teaching of reading were debated; the board and the superintendent quarreled over authority. Yet as the public school system grew and offered more diverse services, it provided its large immigrant and working class constituents a valuable educational ladder to inclusion in the Milwaukee community.

Growth and Consensus—The Golden Age, 1914 to 1960

The 1914 to 1960 time period was one of impressive growth for the city and MPS. In 1920 Milwaukee had 457,000 residents; by 1960, 741,000. The K-12 enrollment in 1917 was 54,000; by 1960, 101,000. The 1946-60 period saw the building of forty new schools to accommodate the baby boom; whereas the city had five public high schools in the early 1920s, there were thirteen by 1961. From 1906 to 1967 Milwaukee voters approved 27 of 29 requests for tax levies or bond issues for educational improvements and construction, indicating citizen satisfaction with MPS.[4] This approval owed much to strong German and socialist traditions which valued education highly. The socialists were ardent backers of a full-service, well-funded public school system, staffed according to merit.

Despite the rapid growth, MPS’ leadership was remarkably stable, another indication of broad public approval. Milton Potter was superintendent from 1914 to 1943; Lowell Goodrich, 1943 to 1949; and Harold Vincent, 1950 to 1967. From 1920 to 1953, the average tenure of a high school principal was eleven years.[5] Board elections were generally free of partisan politics, and the board and superintendent did not experience the more intense and persistent pressures from federal, state, and local community interests with which MPS authorities would have to deal after 1960. There were board-central office tensions, but overall the board deferred to the strong superintendents and Potter, especially, guided curriculum changes. The belief of MPS and city leaders that they had achieved admirable success and consensus would inevitably imbue them with a prideful defense of the status quo, not a useful mentality for the changes that would come after 1960.

The flood of baby boomers into schools in the post-World War II years necessitated a doubling of the teacher staff from 1947 to 1967. Gradually, new teachers came with more extensive training; by the 1930s all new hires were required to have college degrees. The city’s industrial-induced prosperity enabled an adequate revenue base and MPS teacher pay, while not generous, was favorable compared to that of most other Wisconsin school districts. General teacher satisfaction is indicated by the fact that during the 1925-40 time, one-third to two-thirds of elementary teachers remained at the same school for at least fifteen years.[6] Nevertheless, without a strong union (until 1963) teachers as a whole had little voice in decision-making beyond their classroom procedures. Women were still a majority of all teachers, and the baby boom flood wiped away much of the bias against employing married females. A spurt in high school enrollment brought more males into teaching; by the 1950s they were a majority in the high schools.[7]

Increasing recognition of learning deficits meant an increase in specialized teachers, support staff, and central office supervisors. More psychologists, social workers, guidance counselors, and nurses were employed. Classes for the physically and emotionally challenged were added. By 1970 MPS managed to reduce the average class size to twenty-eight. In the 1920s junior highs were introduced (Lincoln was the first one), and by 1960, K-8 schools had been largely replaced by K-6 schools and junior highs (7-9). The comprehensive high school continued to serve a diversity of students with its general, commercial, and college prep strands. Washington, Riverside, Marshall, and Boys Tech high schools gained reputations for quality education. The movement on behalf of progressive education dominated the 1914-60 period, with an emphasis upon preparing students for productive careers and citizenship. Pedagogy meant less rote learning, whereas typing, home economics, bookkeeping, and industrial skills were embedded in the curriculum. In the 1950s standardized testing began. At the same time, many schools began to house social centers, adult programs, and recreation leagues.

1960-2010: Demographic Changes Brought Conflicts and a Vastly Different MPS

Stability and broad citizen approval of MPS weakened in the post-1960 era. The main causes were demographic shifts: an in-migration of thousands of African Americans—and then Hispanics—and flight from the city and its public schools of thousands of whites. By the 1984-85 school year African American students had become a majority of MPS enrollment.

Table 1: Racial Composition of Milwaukee Population and Milwaukee Public Schools Students, 1970, 1985, and 2010

| 1970 | 1985 | 2010 | |

| White % of city population | 82 | 67 | 45 |

| White % of Milwaukee Public Schools students | 70 | 36 | 14 |

| Black % of city population | 15 | 23 | 40 |

| Black % of Milwaukee Public Schools students | 26 | 53 | 58 |

| Hispanic % of city population | 17 | ||

| Hispanic % of Milwaukee Public Schools students | 23 |

Historically, Milwaukee has been a racially segregated city, especially in terms of residency. When assigning students to schools, MPS had adhered to a neighborhood school policy, which meant that most public schools became highly segregated.

Table 2: 1963-1964 Number of Schools Per Percentage of Nonwhite Pupils

| 0-10% | 10-33% | 33-67% | 67-90% | 90-100% | |

| Elementary Schools | 86 | 11 | 2 | 4 | 13 |

| Junior High Schools | 11 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Senior High Schools | 8 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

The 1954 United States Supreme Court Brown v. Board of Education decision ruled deliberate racial segregation in public schools to be unconstitutional. There were some who believed all segregation to be detrimental; African American attorney Lloyd A. Barbee was one. Beginning in 1963 he and a core of black and white allies began a campaign to desegregate MPS. They claimed that most African American students bore the burden of older, overcrowded facilities, inferior school materials, and less experienced teachers. The insurgents pointed to “intact busing” as an example of the racism of school authorities: black students in overcrowded schools in the midst of reconstruction were bused to white schools but were taught in separate classes, were kept apart from white children at recess, and were bused back to their home school for lunch.

Barbee created the Milwaukee United School Integration Committee (MUSIC), which called for racial balance in all MPS schools. From 1964 to 1966 MUSIC employed picketing, non-violent civil disobedience, and three school boycotts. But the school board made no significant concessions, and in 1965 Barbee filed suit in federal court, claiming deliberate segregation by school authorities.

In January 1976 federal Judge John Reynolds ruled that school authorities had deliberately pursued segregationist policies. In addition to the intact busing program, Reynolds noted that in sixty-three board decisions involving school boundary changes, only one had fostered racial integration.[8] Reynolds ordered the system to begin school desegregation in the fall of 1976. Many Milwaukee whites, including Mayor Henry Maier and a majority of the school board, opposed the order, but over the course of the next three years, Milwaukee experienced one of the most wide-ranging and peaceful school desegregations in the nation. By the mid-1980s, 85 percent of MPS students attended racially integrated schools.[9]

The desegregation plan that guided this transformation was the product of superintendent Lee McMurrin (1975-1987) and his deputy David Bennett. It relied heavily on busing African American students into predominantly white schools, thus placing nearly 90 percent of the “burden of busing” on blacks.[10] It converted a number of previously all-black schools into magnet and specialty schools, advertising high quality instruction in order to encourage voluntary integration by whites. Thus, north side Rufus King High became a college prep magnet and West Division became magnet School of the Arts; both received acclaim. Also praised have been the French and German language immersion schools and a Montessori school. Research has revealed that magnet schools drew disproportionately from Milwaukee’s white and black middle class.[11] 1976 also saw the beginning of the Chapter 220 program whereby suburban schools have been encouraged, by grants of state money, to enroll minority students from Milwaukee. Further, the post-1960 time period saw a significant increase in minority teachers and principals. By 1985, 35 percent of principals were non-white, and by the late 1990s, 25 percent of MPS teachers were non-white.[12] Robert Peterkin (1988-1991) and Howard Fuller (1991-1995) were the first two African American superintendents of MPS. In 1978 the school board was reduced to nine members (from fifteen), eight of whom were elected by district; this enabled minorities to increase their representation on the board.

During the 1976-95 years, a majority of Milwaukee blacks surveyed expressed modest approval of MPS desegregation. But many were critical of the one-way busing and the apparent failure of the non-magnet schools to produce hoped-for achievement gains with low-income African American students. Standardized test scores of African American students, most of whom were from low-income families, remained low; the black failure-to-graduate-in-four-years rate was consistently in the 40-50 percent range.[13] Rising conflict was mirrored within the Milwaukee Board of School Directors which previously had been relatively free of bitter contention. From 1963 to the mid-1980s the issue of desegregation split the board; in the 1980s and 1990s conflicts pitted pro-business against pro-labor factions, prompted by the rise of the union, the Milwaukee Teachers Education Association (MTEA). The MTEA grew in power and negotiated highly favorable healthcare and pension benefits for teachers; the union fought tenaciously for seniority rights and against requiring teachers to live in Milwaukee. Educators’ dissatisfaction was reflected in high turnover rates for teachers, principals, and superintendents (from 1988 to 2010, for instance, the average tenure of superintendents was not quite four years).

By the 1980s the broad public approval of MPS that existed during the 1914-1960 era had dissolved as a number of contentious groups emerged. Many white families, opposed to school integration and dismayed with deteriorating school order, began sending their children to private schools or moved out of the city. Between 1976 and 1985, one-third of white school age children left the city and of those who remained one-half attended private schools.[14] The declining status of MPS was also a result of the economic condition of Milwaukee families. Few American cities suffered from the deindustrialization of the post-1960 years as much as Milwaukee. The city’s economic well-being was heavily dependent on production jobs—and no group more so than African Americans. In 1970 the city’s average black household income was nearly 19 percent above the national black average, primarily because of unionized industrial jobs. Between 1963 and 2002 Milwaukee lost a net 84,000 factory jobs. By 2000 the average black household income was 23 percent lower than the national black average; the black unemployment rate was one of the highest in the nation; and so was the rate of black poverty.[15] The rise of youth gang and drug-induced violence drove the black middle class out of the inner city. Moreover, where restless teens once left school after eighth grade for available jobs, now these youth were required to be in school. Teaching and learning encountered unprecedented obstacles.

Realizing that white flight would doom MPS integration and overwhelm the schools with low-income students, white and black integration leaders urged a desegregated metropolitan district. This led MPS to bring suit against twenty-four suburbs, claiming their deliberate attempt to keep African Americans out of their districts. An out-of-court settlement in 1987 increased the number of Milwaukee minority children who could transfer into suburban schools via the 220 program. At the program’s height, about 6,000 Milwaukee minority students a year were getting an integrated education in suburban schools.[16]

The possibility of true integration within MPS remained out of reach, and activists turned to reforming MPS. One group, led by board members Joyce Mallory, Jeanette Mitchell, and Mary Bills and superintendents Robert Peterkin and Howard Fuller, sought to reform MPS from within, stressing primary grades success, decentralization of authority, less busing, and higher standards. Another group argued that because MPS was so mired in a bureaucratically enforced status quo, turning to schools outside of MPS was imperative. This group, led by state legislator Annette Williams and Fuller (pre-and post-superintendence), lobbied strongly for a voucher program by which low-income parents would receive public funds to enroll their children in private, nonsectarian schools. Voucher supporters argued that parents should have more choices, and that private schools frequently provided quality education in a more disciplined classroom and at lower cost. In 1990 the state legislature approved a voucher program for Milwaukee students. Only a few years later the program was expanded to include religious schools. Milwaukee was at the national forefront in the voucher movement.

By the 2009-10 school year, there were approximately 120 voucher schools serving 21,000 students.[17] Evaluation of the voucher schools indicated that voucher students did not perform significantly better academically than comparable MPS students. However, there was evidence that voucher high schools had better graduation rates than did MPS high schools.[18] Another alternative to MPS emerged in 1998 when the legislature allowed the Milwaukee Common Council and the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee to sponsor charter schools, institutions that would be publicly funded but subject to fewer regulations than MPS schools. MPS responded by creating its own charter schools.

Thus, over the course of 1960-2010, Milwaukee went from a unified public school system alongside private/parochial schools to a fragmented system of schools that received public funds and included many more options, based on parent approval. Enrollments in these various options in the 2009-10 school year are shown here:

Table 3: Numbers of Milwaukee Students in Different Kinds of Schools, 2009

| MPS conventional schools | 7,940 |

| MPS partnership schools | 2,309 |

| MPS charters | 2,195 |

| Charters outside of MPS | 5,900 |

| Private voucher schools | 21,062 |

| Open enrollment into suburbs | 5,193 |

| Chapter 220 into suburbs | 2,409 |

The racial and economic upheavals in MPS and its poor performance record led to the intrusion of an unprecedented number of non-MPS authorities into educational decision-making in the post-1960 years: the federal government; the state legislature, governor, and Department of Public Instruction; state and federal courts; city hall; business leaders; foundations; and citizen advocacy groups, such as MUSIC and pro-voucher supporters.

The post-1960 era meant structural and curriculum changes for MPS. Declining enrollments, from a peak in the low 130,000s in the early 1970s to around 80,000 by the end of the first decade of the twenty-first century, led to a number of school closings; other schools were combined. In the 1970s junior highs (grades 7-9) were transformed into middle schools (grades 6-8). In the nineties there was a move back to K-8 schools in order to establish greater continuity and stability. The language arts curriculum was given a greater multicultural emphasis, and algebra was required of all students by the ninth grade. MPS and the state raised standards for graduation. Frequent standardized testing was introduced.

Studies have consistently shown a high correlation between poverty and lower academic achievement; according to one source, Milwaukee has one-third of Wisconsin’s poor children, but gets just one-seventh of state public school funding.[19] This begins to tell the story of MPS’ increasingly problematic revenue situation in the post-1960 era. Deindustrialization and middle class flight from the city significantly weakened the tax base. Healthcare and pension benefits to employees and retirees became a heavy burden on the MPS budget. These factors have resulted in cuts to MPS programs and staff. In some cases art, music, and gym classes were eliminated and typical class sizes grew to the 30-40 range.[20]

Since the 1950s, once proud MPS has been severely buffeted by economic devastation, an influx of many low-income black and Hispanic families, and the flight of many middle class households. The results are a much-changed Milwaukee educational landscape and challenges that will take many shoulders to the wheel to reach higher ground.

Footnotes [+]

- ^ Rolland Callaway, The Milwaukee Public Schools: A Chronological History, 1836-1986. Volume I: Formative Years, 1836-1915, ed. Steven Baruch, (Milwaukee: Caritas Communications, 2008), CD format, 41, 213, 239; Kathleen Neils Conzen, Immigrant Milwaukee, 1836-1860: Accommodation and Community in a Frontier City (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1976), 91-92, 180-82; William M. Lamers, Our Roots Go Deep, 1836-1967, 2nd ed. (Milwaukee: Milwaukee Public Schools, 1974), 8. This entry was first posted on August 13, 2018 and revised on June 5, 2019.

- ^ Callaway, The Milwaukee Public Schools, 57-58; Lamers, Our Roots Go Deep, 9, 12.

- ^ Callaway, The Milwaukee Public Schools, 74; Lamers, Our Roots Go Deep, 6.

- ^ Lamers, Our Roots Go Deep, 68.

- ^ William J. Kritek and Delbert Clear, “Teachers and Principals in the Milwaukee Public Schools,” in Seeds of Crisis: Public Schooling in Milwaukee since 1920, ed. John L. Rury and Frank A. Cassell (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1993), 166.

- ^ Kritek and Clear, “Teachers and Principals in the Milwaukee Public Schools,” 167.

- ^ Kritek and Clear, “Teachers and Principals in the Milwaukee Public Schools,”, 149.

- ^ Amos et al v. Board of School Directors of Milwaukee 65-C-173, January 19, 1976, 793, 812-13.

- ^ David I. Bednarek, “Despite McMurrin’s Efforts, Integration Battle Isn’t over,” Milwaukee Journal, July 28, 1987.

- ^ Bill Dahlk, Against the Wind: African Americans and the Schools in Milwaukee, 1963-2002 (Milwaukee: Marquette University Press, 2010), 319, 326.

- ^ Dahlk, Against the Wind, 426.

- ^ Janelle Elder-Green, “School Official Disputes Community Journal Editorial,” Milwaukee Community Journal, May 13, 1987; Martin Haberman, “Increasing the Number of High-Quality African American Teachers in Urban Schools,” accessed January 5, 2015, http://www.habermanfoundation.org/Articles/Default.aspx?id=66.

- ^ Dahlk, 424-25, 558, 626.

- ^ Bruce Murphy and John Pawasarat, “Why It Failed: Desegregation in Milwaukee Ten Years After the Landmark Ruling,” Milwaukee Magazine, September 1986, 36, 43.

- ^ Dahlk, Against the Wind, 438, 627-29; Marc V. Levine, “The Crisis of Black Male Joblessness in Milwaukee: Trends, Explorations, and Policy Options,” Center for Economic Development Working Paper, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2007.

- ^ Erin Richards, “As School Options Expand, Landmark Chapter 220 Integration Program Fades,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, December 24, 2013.

- ^ Alan Borsuk, “Any Way You Slice It, School Choice Shapes City Education,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, November 29, 2009.

- ^ Erin Richards, “MPS, Voucher Students Boost Graduation Rates,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, January 11, 2011; Erin Richards and Amy Hetzner, “Choice Schools Not Outperforming MPS,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, March 29, 2011; Erin Richards, “Voucher Testing Data Takes New Twist,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, March 30, 2011.

- ^ Jack Norman, “District Enjoys National Reputation,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, April 19, 1995.

- ^ Alan J. Borsuk, “Class Size Hike Spells Trouble,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, May 15, 2011.

For Further Reading

Anderson, Harry, and Frederick Olson. Milwaukee: At the Gathering of the Waters. Tulsa: Continental Heritage Press, 1984.

Callaway, Rolland. The Milwaukee Public Schools: A Chronological History, 1836-1986. Edited by Steven Baruch. Milwaukee: Caritas Communications, 2008. CD format.

Dahlk, Bill. Against the Wind: African Americans and the Schools in Milwaukee, 1963-2002. Milwaukee: Marquette University Press, 2010.

Dougherty, Jack. More Than One Struggle: The Evolution of Black School Reform in Milwaukee. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004.

Lamers, William J. Our Roots Go Deep, 1836-1967. 2nd ed. Milwaukee: Milwaukee Public Schools, 1974.

Nelsen, James K. Educating Milwaukee: How One City’s History of Segregation and Struggle Shaped Its Schools. Madison, WI: Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 2015.

Reese, William J. Power and the Promise of School Reform: Grassroots Movements during the Progressive Era. Boston, MA: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1986.

Rury, John L., and Frank A. Cassell, eds. Seeds of Crisis: Public Schooling in Milwaukee since 1920. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1993.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.