Any conversation regarding local government in Wisconsin must begin—and ultimately conclude—with mention of the State (or, to be more precise, of the territories of Michigan or Wisconsin, succeeded in time by the State of Wisconsin). In essence, either the state constitution or its statutes determine the purposes, powers, and prerogatives of local governments, down to their very existence. Counties, towns, villages, cities, school districts, and other special jurisdictions (including those dealing with water, sewerage, or community colleges) depend for their authorization and survival upon the whim of the State. Local governments in Wisconsin are extra-jurisdictions permitted by the State for the purpose of carrying out specific responsibilities that are handled more efficiently and, often, more effectively in locales situated closer to the daily lives of Wisconsin residents (such as public safety). But every duty or power exercised by local authorities can be altered quite dramatically through either state laws or amendments to the state constitution.

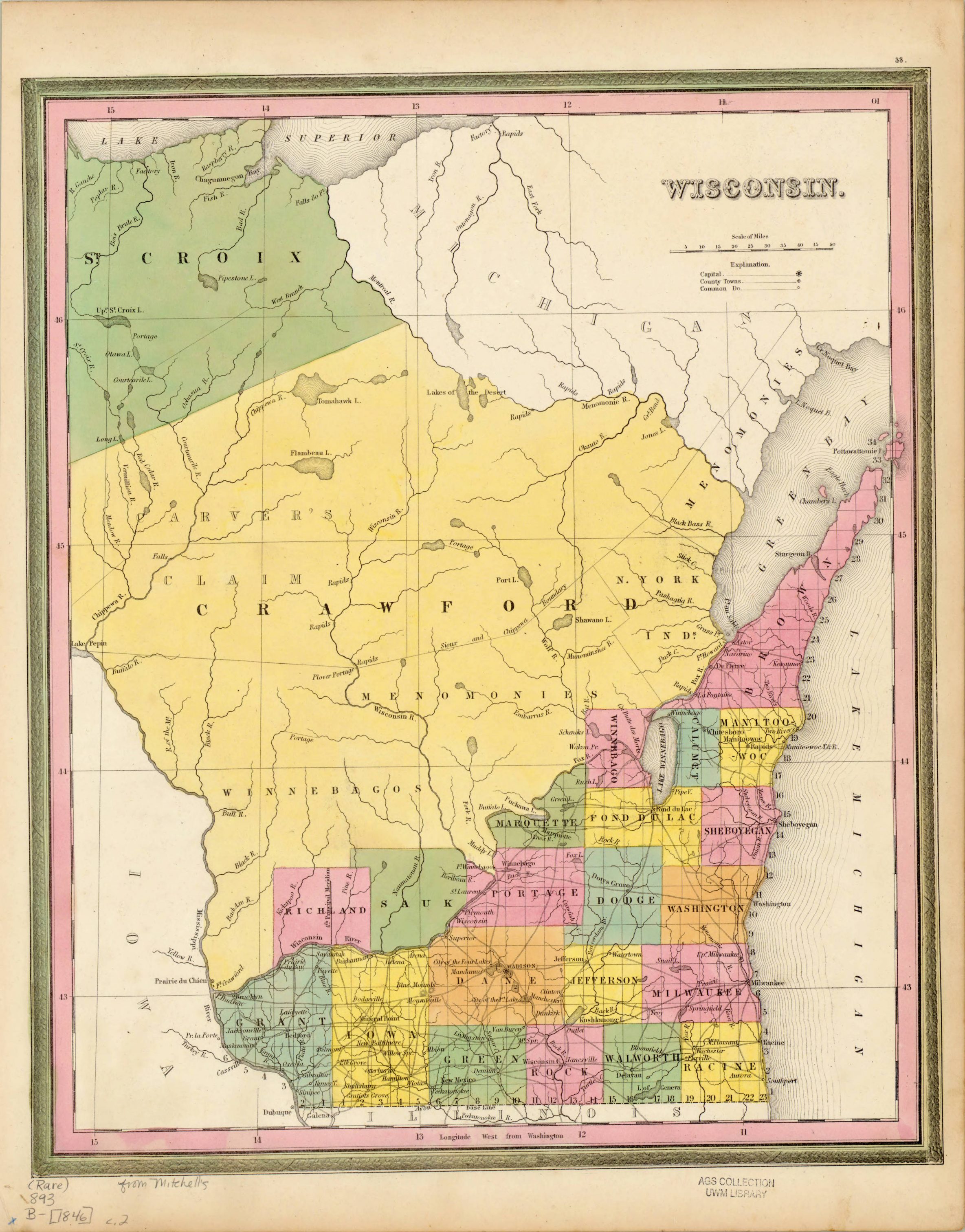

The first subordinate political entities serving what would eventually become Wisconsin resulted from actions taken by the Michigan territorial governor in 1818 when he created three counties to address matters in the westernmost half of his jurisdiction (that is, the lands that would become the Territory of Wisconsin and, subsequently, the State of Wisconsin). One of these three jurisdictions, Brown County, administered the eastern portion of what became Wisconsin, including the Milwaukee area.[1] Sixteen years later, in September 1834, an oversized Milwaukee County was carved from its predecessor, with this newest jurisdiction including all of Southeast Wisconsin. Within two years, however, as Wisconsin moved toward territorial status and Michigan made parallel progress toward statehood, this oversized Milwaukee County was slimmed down by subdivisions: two counties to the north and northwest (Dodge and Washington counties—the latter which then included the future Ozaukee County as well), Jefferson County to the west, Racine County (along with the future Kenosha County) to the south, and Rock and Walworth counties to the southwest. Following a series of strident disagreements and subsequent negotiations during 1846—including a short-term relocation of Milwaukee’s county seat to Prairieville (soon to be renamed Waukesha)—Milwaukee’s sixteen most western townships became parts of yet another new county named Waukesha.[2] In similar moves toward greater local control, Kenosha County was detached from Racine County in 1850 and Ozaukee County from Washington County three years later.[3]

Shortly after the twentieth century opened, there were seventy-one counties across Wisconsin (with one final county coming aboard in 1959 with establishment of Menominee County). The State of Wisconsin’s 1848 Constitution directed the legislature to create counties. However, the exact duties, powers and structure of these jurisdictions would be realized only through experience. The state government (the legislature, governor’s office and, on occasion, the state supreme court) has endlessly adjusted and readjusted the authority of Wisconsin counties since 1848, with some actions granting addition options and others curtailing prerogatives.[4]

In essence, counties are the handmaidens of the State, with several local offices specifically designated as conducting state business, such as the county sheriff and district attorney.[5] Roads, schools, and civil order were the principal concerns of these state subordinates in the beginning.[6] Then, over many decades, social service assignments multiplied for these jurisdictions, including job training, health care, and child welfare. From the outset, management of each county was turned over to a board of supervisors. For a time in the mid-nineteenth century in various counties, these officials were elected at large, representing the entire county. Today, however, supervisors represent specific, geographical sub-districts and the constituents therein. The size of a county board is tied to a county’s population, following a time when looser guidelines led to oversized assemblies such as a ninety-member board of supervisors in Dane County. Milwaukee is one of two counties operated by a different set of arrangements regarding the size of its board.[7] Supervisors are elected for two-year terms on a non-partisan basis. By law, boards must meet at least twice a year, although monthly sessions are the norm in Southeast Wisconsin counties. Supervisors complete most of their work through committees, with passage of ordinances or resolutions coming from actions by the full board. The range of decisions that a board may undertake is often restricted because state statutes direct what the counties “shall” do, whereas others are written such that these jurisdictions “may” undertake a range of options.[8]

As the health and social service responsibilities of Wisconsin counties multiplied in the World War II era, the need for greater oversight of daily activities led Wisconsin voters to adopt a constitutional amendment in 1962 allowing Milwaukee County to elect a “county executive.” Chosen for a four-year term, this individual would draft a budget for the supervisors’ review as well as oversee the administration of everyday responsibilities across the county’s many departments. Seven years later, the idea had caught on, leading to another constitutional amendment allowing any county to adopt such a management format. Since counties are now required to have a central administrative officer, as one alternative counties may prefer to appoint such an individual (rather than elect this person) for an indefinite term. This board-appointed executive is referred to as a “county administrator,” an individual who does not have veto power over board actions in contrast to a county executive. Still, in other counties (typically smaller counties), a full-time or part-time “administrative coordinator” may be appointed, with powers as granted by the county board. Statewide, as of 2018, eleven counties have executives and twenty-eight have administrators. Locally, Milwaukee, Racine, and Waukesha counties have county executives, whereas Ozaukee and Washington counties have county administrators.[9] Additional examples of the state-assigned roles can be found in the offices mandated by either the constitution or by statute. These elected officials, who run on a partisan basis, include the sheriff, the district attorney, the clerk, and the registrar of deeds. Appointed officers include medical examiners and surveyors.[10]

To further serve the State, counties in the Badger State were divided into towns, beginning in 1827 when the Territory of Michigan still governed Wisconsin. Every corner of a county started out as part of some town, with subsequent detachments from these towns through the incorporation of new jurisdictions known as villages or cities. In earlier days, towns were segments of land arranged to handle local services in rural settings, especially issues pertaining to roads, schools, and small-scale justice issues handled by justices of the peace and constables. More recently, some land use decisions have been added to their concerns.[11] Out these towns (which varied in number per county) arose, over time, incorporated jurisdictions known as villages and cities, although, it should be noted, 1,253 towns were still carrying out their duties across the state in 2017-18.[12] Ozaukee and Racine counties have six towns each, Washington County twelve towns, and Waukesha County eleven towns. In contrast, Milwaukee County has no towns left because every portion of this county had been incorporated into either a village or a city.[13]

Towns in Wisconsin should not be confused with what are variously referred to as federal or congressional or survey townships. These precise dissections of land in, first, the territory of Michigan, then the Territory of Wisconsin, and finally the State of Wisconsin, were created to provide orderly ownership for each piece of property across areas that were originally federally-owned lands. A survey township typically consisted of a thirty-six square mile jurisdiction, subdivided into one-mile sections, and then further subdivided into smaller and smaller plots.[14] In some counties of Wisconsin, the boundaries of these federal townships coincided spatially with the later state-approved subdivisions of counties that became known as towns, but in many other sections of the territory and later the state, there was no locational match between a state-authorized town and a survey township.

A Wisconsin town typically becomes smaller over time as subsections incorporate into independent villages and cities. Towns can even cease to exist, as has occurred with Milwaukee County. Thus what was once the Town of Greenfield over time morphed into cities such as Milwaukee and Greenfield or villages such as Greendale and Hales Corners. Towns, under the direction of three to five supervisors who are elected at-large for non-partisan, two-year terms, typically collect taxes, hold elections, and oversee local roadway maintenance. An town meeting must be held annually, but everyday concerns are administered by a town board that choses its leader (town chairman) to facilitate its work. Other mandated offices in towns include a clerk, a treasurer, and an assessor. Most town officials serve in part-time capacities. Again, the fulfillment of their duties, even though they may not realize it, make them localized agents for the State of Wisconsin.[15]

Through ever-adjusting processes, subsections of these towns (and by extension these counties) may incorporate into one of two jurisdictions: a village or a city. Historically, incorporation results from the wishes of residents within a certain area for greater governmental services, even if these improvements required additional taxation. Town governments tend to limit their outreach to road maintenance and some zoning oversight. In rural settings, which predominated across Wisconsin well into the twentieth century, this handful of assignments for town governments sufficed for most of the population. However, in places where the settlement thickened and neighbors lived elbow to elbow, matters of water and sewerage systems came to the forefront, along with subsequent concerns over street lighting, sidewalks, animal control (especially over keeping farm animals in restricted confines), and ultimately the proximity of policing agencies when a sheriff’s station twenty or thirty miles away no longer sufficed.

Even in territorial Wisconsin, statutory legislation permitted incorporation of a village or city following upon a petition by potential residents of this new municipality and subsequent legislative approval. From the outset, cities had enhanced authority compared to villages. In both instances, however, these municipalities are guided by a combination of constitutional provisions and state statutes—the latter which can be quite precise. Early on, nearly every change of any consequence had to be approved by the territorial or state legislature. Then in 1871, a general charter law was established for villages, followed twenty-one years later by the same for cities. These actions established generalized rules for municipalities. Following the drift of state and local policy across the country, in 1924 Wisconsin passed a constitutional amendment that established “home rule” for villages and cities—more of an “unless forbidden” approach to municipal management. Otherwise, every action, for instance, toward a police force or a police board or a police pension system had to go before the entire state legislature for approval—this in the case of dozens and later hundreds of municipalities. The same was true for public libraries, parks systems, sewerage, and water systems. Home rule was intended to give municipalities the semblance of political adulthood, although courts subsequently ruled that the state constitution vests “primary even plenary authority” over a considerable list of matters to the legislature, including “organizational arrangements” and “local procedures.”[16]

Villages and cities are carved out of subsections of towns, with residents on one side of the street sometimes living in a new municipality while their neighbors across the street still reside within the original town. Towns did not (and do not) have a say in these subdivisions of their jurisdictions. Only the residents of a potential municipality, with judicial and state oversight, have a say in voting to establish a village or city. By 1988, Milwaukee, for instance, had undergone nearly 500 boundary changes, expanding in size from 7.4 square miles to 96.5 square miles. During decades under socialist mayors, the city aggressively expanded through the annexation of lands from adjacent towns.[17] Expansion could also come from the consolidation of two municipalities, such as the 1887 merger of the City of Milwaukee with the Village of Bay View. Even here, the major motivation for Bay View in losing its civic sovereignty (so to speak) was an improvement in municipal services.[18]

In a village, administrative oversight is handled by an elected board of trustees and by an official known as a president. In addition, a village manager or administrator may appointed to direct the daily affairs of larger communities. A major responsibility of village boards pertains to the finances of its municipality, including budget oversight. Village boards in the greater Milwaukee area consist of six members, half of them chosen annually for two-year terms. Neither the president of the village nor its manager (or administrator) has veto powers over board actions.[19] As of 2017-18, there were 411 villages across Wisconsin, with six in Washington County, seven in Ozaukee County, nine each in Racine and Milwaukee counties, and nineteen in Waukesha County.[20]

In contrast, in a city, municipal management is handled by a council (whose size varies from as few as five to as many as fifteen) and a mayor, although the latter’s powers are limited or expanded by whether there is a weak or a strong mayoral system in force. In the former, the mayor tends to be more a figurehead, representing the city at formal events while serving in the common council as simply a member. In the case of the latter, the mayor drafts budgets for council approval, appoints department chiefs, and has veto power over council actions. Cities, like villages, have their own charters to provide structure for the operation of governmental responsibilities as well as the electoral process.[21] As of 2017-18, there were 190 cities in Wisconsin, with three in Ozaukee County (Port Washington, Cedarburg, and Mequon), two in Racine County (Burlington and Racine), three in Washington County (Hartford, a sliver of Milwaukee, and West Bend), eight in Waukesha County (Brookfield, Delafield, another sliver of Milwaukee, Muskego, New Berlin, Oconomowoc, Pewaukee, and Waukesha), and ten in Milwaukee County (Cudahy, Franklin, Glendale, Greenfield, Milwaukee, Oak Creek, South Milwaukee, St. Francis, Wauwatosa, and West Allis).[22] It should be noted at this point that it is not unusual to have two jurisdictions referencing the same name such as the Town of Belgium and the Village of Belgium or the Town of Oconomowoc and the City of Oconomowoc.

Wisconsin is filled with over 1,100 special districts that typically address specific, regional-oriented concerns such as technical colleges, sewer and sanitation systems, sports venues (Miller Park and Lambeau Field), lake management, and regional planning. Overseers of these districts are elected in some instances and appointed in others. School districts that handle elementary and secondary education are the oldest of these special districts. These jurisdictions typically have taxing powers to fund their stated purposes, revenue that is realized through property tax bills, sales taxes, or quarterly billing cycles. In the greater Milwaukee area, these special districts include the Metropolitan Sewerage District, the Wisconsin Center District (which oversees the Wisconsin Center the UW-Milwaukee Panther Arena, and Miller High Life Theatre, and SEWRPC (the Southeast Wisconsin Regional Planning Commission).[23]

In total, over 3,000 jurisdictions shape the quality of life of Wisconsinites. Ultimately, these jurisdictions are all entities designed to serve the State of Wisconsin, influencing daily routines from the roads on which we drive to educating youngsters to housing criminals to the stadium for watching major league ball games. Somewhere in this vast system, powers and responsibilities are altered annually by state action. For this reason, voters must remain vigilant of the intricate influences that elected officials have over their everyday well-being.

Footnotes [+]

- ^ Ellen D. Langill and Jean Penn Loerke, ed., From Farmlands to Freeways (Waukesha, WI: Waukesha County Historical Society, 1980), 87, 95; James R. Donoghue, Local Government in Wisconsin (Madison, WI: Wisconsin Assembly, 1979), reprint from Wisconsin Blue Book, 1979-80, 26.

- ^ Langill and Loerke, From Farmlands to Freeways, 91-94.

- ^ Racine County, Wisconsin website, accessed July 21, 2017; Ozaukee County, Wisconsin website http://www.co.ozaukee.wi.us/, accessed July 21, 2017 and August 9, 2017.

- ^ Langill and Loerke, From Farmlands to Freeways, 95, 98; Donoghue, Local Government in Wisconsin, 26.

- ^ Wisconsin Taxpayers Alliance, The Framework of Your Wisconsin Government (Madison, WI: Wisconsin Taxpayers Alliance, 1997), 51, 55-56 (hereafter referred to as WTA); Langill and Loerke, From Farmlands to Freeways, 97. In 2018, the Wisconsin Taxpayers Alliance merged with the Public Policy Forum to create the Wisconsin Policy Forum.

- ^ Christopher Mark Miller, “Milwaukee’s First Suburbs” (Ph.D. diss., Marquette University, 2007), 16-18.

- ^ Donoghue, Local Government in Wisconsin, 27-28; WTA, 54; Langill and Loerke, From Farmlands to Freeways, 95-96.

- ^ Donoghue, 32; WTA, 51-53; Langill, 97.

- ^ Donoghue, Local Government in Wisconsin, 27, 35-36; WTA, 54-55; State of Wisconsin, Blue Book, 2017-18 (Madison, WI: Wisconsin Legislative Reference Bureau, 2017), 385-386, accessed July 10, 2018; County Government Authority, Administrative Structure Options, and the Roles and Responsibility of County Board Members, accessed October 12, 2018.

- ^ WTA, 55-56; State of Wisconsin, Blue Book, 386.

- ^ Miller, “Milwaukee’s First Suburbs,”15-18; State of Wisconsin, Blue Book, 387.

- ^ State of Wisconsin, Blue Book, 387.

- ^ State of Wisconsin, Blue Book, 602, 604, 607-08.

- ^ Irene D. Lippelt, “Understanding Wisconsin Township, Range, and Section Land Descriptions,” Wisconsin Geological and Natural History Survey, Educational Series 44 (Madison, WI: Wisconsin Geological and Natural History Survey, 2002).

- ^ WTA, 64-67.

- ^ Donoghue, Local Government in Wisconsin, 45-48.

- ^ Arnold Fleischman, “The Territorial Expansion of Milwaukee,” Journal of Urban History, 14, no. 2 (February 1980): 149-164.

- ^ Miller, “Milwaukee’s First Suburbs.” chapter 1.

- ^ WTA, 71, 74-76; Donoghue, Local Government in Wisconsin, 60-61; State of Wisconsin, Blue Book, 387.

- ^ State of Wisconsin, Blue Book, 601, 602, 603-04, 607-08.

- ^ WTA, 71-79.

- ^ State of Wisconsin, Blue Book, 387; Ozaukee County, Wisconsin website, accessed July 21, 2017 and August 9, 2017.

- ^ Wisconsin Center District website; State of Wisconsin, Department of Revenue website; Wisconsin Legislative Reference Bureau Digital Collections website, all accessed on June 25, 2018; State of Wisconsin, Blue Book, 390-393.

For Further Reading

Donoghue, James R. Local Government in Wisconsin. Madison, WI: Wisconsin Assembly, 1979.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.