Although now much smaller in scale, meatpacking was one of Milwaukee’s leading industries through much of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and the most prominent form of food processing in the city. The industry and city grew together as firms slaughtered, processed, and packaged livestock—particularly hogs and cattle—from hinterland farms, distributing products for regional, national, and international markets.

Like many of its major food processing trades, Milwaukee’s meatpacking industry started out small. It is unclear who had established Milwaukee’s first butcher shop.[1] However, a number of modest operations emerged in the 1840s that produced a limited amount of meat for neighbors from animals they housed and slaughtered in their own yards.[2] This meat—primarily beef and pork—was often sold fresh in warmer months, preserved in salt for winter months, or made into a number of different fresh or cured sausages in accordance with the ethnic food cultures of the butchers and the communities they served.[3] Small butcher shops served neighborhoods and local communities throughout Milwaukee’s history. However, a few of these operations expanded into industrial packinghouses that later supplied regional, national, and eventually international markets.

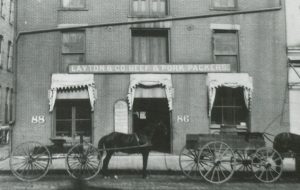

The most notable of these pioneering meatpackers were John Plankinton and Frederick Layton. Born in Delaware and having worked for butchers in Pittsburgh, John Plankinton opened a butcher shop on Spring Street (now West Wisconsin Avenue) shortly after his arrival to Milwaukee in 1844 and quickly expanded into preserving and packing meat for shipment to other markets.[4] In 1845, John and Frederick Layton, experienced butchers from Cambridgeshire, England, established a butcher shop on East Water Street (now North Water Street). They found early success in supplying local hotels and boardinghouses with pork, beef, and mutton.[5] Frederick Layton and John Plankinton formed a partnership in 1852, opening a facility devoted to the preserving and packing of large amounts of pork and beef. Layton & Plankinton later expanded their operations to a larger complex in the Menomonee River Valley where fellow meatpackers Thomas and Edward Roddis had also formed a large packinghouse in 1851. As the existing marsh was filled in, and canal and rail networks were developed, the valley’s large, flat areas proved an ideal location for the city’s meatpacking district.[6]

The timing and conditions were right for the meatpacking industry to develop and thrive in Milwaukee in the mid-to-late nineteenth century. Milwaukee’s growing population created an increasing demand for meat—particularly among the city’s Northern Europeans.[7] New rail connections between the city and growing hinterland farms provided a steady stock of live cattle and hogs, later augmented by the shipment of livestock from farms and ranches in western states and territories. Moreover, expanding rail networks and advances in refrigerated shipping also provided the city’s meatpackers with year-round access to Eastern markets.[8] The city’s meatpackers also secured large government orders for packed pork and beef for the Union Army during the Civil War, doubling the amount of meat they processed. These contracts not only boosted the city’s meat industry but also helped create a national demand for Milwaukee meat products.[9] The local meat industry also benefited from the development of ancillary industries—particularly leather tanning—that effectively used up the remaining parts of processed animals.[10] “In the great Milwaukee packing houses,” one account boasted, “not a scrap of the ‘porker’ is wasted.”[11] Milwaukee’s ice industry and Wisconsin winters were also tremendously important to the industry’s growth, providing a natural source for the refrigeration necessary to process, preserve, and ship large quantities of meat in the era before improvements in mechanical refrigeration.[12]

In the decades following the Civil War, Milwaukee joined the ranks of national industry leaders, such that, by 1880, meatpacking had become the city’s leading industry.[13] While the city’s packinghouses continued to process a variety of livestock, including calves, sheep, and cattle, Milwaukee became a key center for pork production.[14] The number of hogs processed by the city’s packinghouses swelled from 88,853 in 1866 to 225,598 in 1876 and 553,077 in 1886.[15]

Such dynamic growth inspired Milwaukee’s largest meatpackers to pursue new opportunities and partnerships. Frederick Layton left John Plankinton to form his own packing company with his father in 1863. One year later, Plankinton formed a partnership with the budding mogul, Philip Armour. In 1884, Armour left the company to lead his family’s meatpacking operation in Chicago. Armour & Company became one of the nation’s most iconic packers.[16] Meanwhile, Plankinton promoted his young plant superintendent, Patrick Cudahy, to junior partner in the firm.[17] Cudahy and his brother John purchased the firm from Plankinton four years later, renaming it Cudahy Brothers.[18]

The industry’s growth also created a need for a “centralized terminal market” that could facilitate livestock transactions between distant farmers and meatpackers more efficiently and profitably.[19] Milwaukee’s first livestock market was located in Haymarket Square.[20] However, the growing number of livestock entering the market created problems as the animals hindered street traffic and occasionally got loose, “roaming Milwaukee streets and damaging gardens.”[21] In 1869, the Chicago, Milwaukee, and St. Paul Railroad Company (in which Plankinton and the Laytons had a substantial stake) constructed stockyards along their rail lines in the Menomonee Valley, modeled after Chicago’s successful Union Stockyards, which had opened four years earlier.[22] Now able to handle nearly a trainload of rail cars at one time, the new yards featured wooden pens (that could hold around 2,000 cattle or 20,000 hogs), efficient drainage, feeding, and watering systems, and a large hotel for visiting farmers and commissioners selling animals.[23] The construction of the stockyards confirmed the Menomonee Valley as Milwaukee’s packing district. By the early 1900s, most of the city’s largest packing firms had established major processing plants in the valley along Muskego Avenue (now South Muskego Avenue and North and South Emmber Lane, separated by an expanded railyard)—in close proximity to the stockyards.[24]

Packinghouses provided significant employment for unskilled laborers. Prior to mechanical refrigeration, packing was seasonal work, limited to cold winter months in order to ensure the safe preparation of meat.[25] In 1879-1880, the workforce at Milwaukee’s largest packer, Plankinton & Armour, fluctuated from as few as 200 to as many as 750 workers.[26] By the 1890s, the adaptation of mechanical refrigeration made packing year-round, increasing plant production and offering more stable work.[27] Employment in Milwaukee’s packinghouses grew from approximately 1,000 workers in 1890-1891 to 1,435 in 1902-1903, 2,450 in 1910-1911, and 3,277 in 1922-1923.[28]

The industry continued to modernize and boom through the turn of the century. In 1893, the Cudahy Brothers moved their operations to a modern plant along the Chicago and North Western Railroad lines two miles south of the city, creating the industrial suburb of Cudahy.[29] In order to facilitate an increasing reliance on motor trucks for livestock shipment, new state-of-the-art stockyards were constructed on Muskego Avenue, closer to the valley’s major packing plants, in 1929.[30] Moreover, war once again bolstered Milwaukee’s meatpackers, who secured large contracts to supply the Allied forces during both the First and Second World Wars.[31]

However, decentralization across the meatpacking industry in the decades following the Second World War spawned a significant decline in Milwaukee’s meat trade. Many older and smaller packinghouses closed as they found it harder to compete with more modernized producers. As historic firms like Plankinton shuttered their operations in the 1960s and 1970s, newer companies like Peck Packing Company expanded. Yet, Peck also succumbed to national pressures, selling its operations to the Sara Lee Meat Group in 1985. The old Peck complex remained in operation in the hands of different companies until Cargill Inc. closed most of its operations in 2014. The company’s ground beef plant is the only remaining facility in the historic Menomonee Valley packing district.[32] The struggling Milwaukee Stockyards had already closed their valley facilities in 2004, moving to a new location closer to livestock farms in Dodge County.[33] While also undergoing a series of acquisitions in the 1970s through 2010s, the Cudahy Corporation nonetheless remained a strong presence in this shrinking industry.[34]

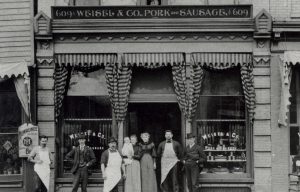

Milwaukee meat firms made a variety of items, but sausages are perhaps the city’s most iconic meat product, with flavors as diverse as the city itself. The sausage industry shares its origins with the meatpacking industry in the city’s many small neighborhood butcher shops. Just as some butchers expanded into major packinghouses in the mid-nineteenth century, others—particularly with roots in the city’s large German population—expanded into large-scale production of sausages in the late-nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. For instance, Jacob Weisel and his nephew Carl Weisel, Sr., both experienced butchers from Cologne, Germany, opened the Jacob Weisel Butcher Shop on East Water Street (now North Water Street) in 1878, specializing in the making of sausages. By the turn of the century, the Weisel Sausage Company had expanded its operations to an industrial sausage plant on Humboldt Avenue, just north of the Milwaukee River. The company grew further in the 1930s-1960s as it expanded into national markets through connections it had made with the city’s brewery distribution networks.[35] By the 1970s, Weisel offered over 60 varieties of sausage (mostly German), and was among the “big three of ethnic sausagemaking” in the United States, along with local rival Fred Usinger, Inc.[36] The Weisel family sold the company to their general manager Thomas G. Stanek in 1977, but the plant closed in 1979 after encountering financial difficulties.[37]

Long-time local giants, Usinger and Klement’s, remain major Milwaukee sausage producers serving regional and national markets while several smaller operations, such as Frank Jakubczak’s European Homemade Sausage Shop on South Muskego Avenue, preserve neighborhood sausage-making traditions. In addition to the bratwurst and hot dogs that have become ubiquitous staples of Milwaukee picnics and ballgames, these sausage-makers continue to produce an array of ethnic varieties—including several German sausages (like knackwurst, bockwurst, and frankfurters), kielbasa, salami, Polish, Italian, Hungarian, and Slovenian sausages, and more recently Mexican Chorizo and Cajun Andouille.[38]

Much like the city’s brewers, Milwaukee’s meatpacking moguls left their mark on the city through major civic contributions. Frederick Layton, for example, established the city’s first art museum, the Layton Art Gallery, on Jefferson and Mason Streets in 1888.[39] John Plankinton also made major contributions to the construction of several local landmarks, including the city’s first downtown Exposition Building.[40] And the Peck family made donations that expanded the Peck School of the Arts at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee in the late twentieth and early twenty-first century.[41]

Footnotes [+]

- ^ Among the first pioneer butcher shops in Milwaukee were those of August Greulich, Edwin Dickerman, and Ralph Johnson, who opened shops in or around 1840. Paul E. Geib, “‘Everything but the Squeal’: The Milwaukee Stockyards and Meat-Packing Industry, 1840-1930,” Wisconsin Magazine of History 78, no. 1 (Autumn 1994): 4; Margaret Walsh, The Manufacturing Frontier: Pioneer Industry in Antebellum Wisconsin 1830-1860 (Madison, WI: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1972), 192.

- ^ Geib, “Everything but the Squeal,” 4; William George Bruce, History of Milwaukee, City and County, vol. 1 (Chicago: S. J. Clarke Publishing Company, 1922), 759; Walsh, 192-194.

- ^ Geib, “Everything but the Squeal,” 4; Bruce, History of Milwaukee, City and County, 1:759.

- ^ John Gurda, The Making of Milwaukee (Milwaukee: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 1999), 118; Walsh, The Manufacturing Frontier, 192.

- ^ Geib, “Everything but the Squeal,” 5; Walsh, The Manufacturing Frontier, 192; John G. Gregory, History of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, vol. 1 (Chicago and Milwaukee: S.J. Clarke Publishing, 1931), 535; “Frederick Layton Is Dead—All City Mourns Loss,” Milwaukee Journal, August 16, 1919, sec. 1, p. 1.

- ^ Gurda, Making of Milwaukee, 118; Walsh, The Manufacturing Frontier, 192; Geib, “Everything but the Squeal,” 7-8, 11.

- ^ Geib, “Everything but the Squeal,” 4.

- ^ Geib, “Everything but the Squeal,”, 4-5, 7-8, 13; Walsh, The Manufacturing Frontier, 193; Industrial History of Milwaukee, the Commercial, Manufacturing, and Railway Metropolis of the Northwest (Milwaukee: E. E. Barton, 1886), 61.

- ^ Gurda, Making of Milwaukee, 101.

- ^ Making of Milwaukee, 119; Industrial History of Milwaukee, 61; Geib, “Everything but the Squeal,” 12-13.

- ^ Industrial History of Milwaukee, 61.

- ^ Geib, “Everything but the Squeal,” 13.

- ^ Gurda, Making of Milwaukee, 119; Geib, “Everything but the Squeal,” 5.

- ^ Geib, “Everything but the Squeal,” 19.

- ^ Gurda, Making of Milwaukee, 119.

- ^ Gurda, Making of Milwaukee, 119.

- ^ Geib, “Everything but the Squeal,” 15.

- ^ Geib, “Everything but the Squeal,” 15.

- ^ Geib, “Everything but the Squeal,”, 5.

- ^ Loren H. Osman, “Trying for a Comeback: Milwaukee Stockyards, Facing Key Decision, Looks to a New Era,” Milwaukee Journal, April 24, 1979, sec. 2, p. 9.

- ^ Geib, “Everything but the Squeal,” 8.

- ^ Geib, “Everything but the Squeal,” 9.

- ^ Geib, “Everything but the Squeal,” 10-11, 18.

- ^ Geib, “Everything but the Squeal,” 17-18.

- ^ Geib, “Everything but the Squeal,” 13.

- ^ Geib, “Everything but the Squeal,” 13.

- ^ Geib, “Everything but the Squeal,”, 14.

- ^ Milwaukee Grain & Stock Exchange, Thirty-Third Annual Report of the Milwaukee Grain & Stock Exchange (Milwaukee: Cramer, Aikens & Cramer, 1891), 52; Geib, “Everything but the Squeal,” 18.

- ^ Geib, “Everything but the Squeal,” 15-17.

- ^ “Everything but the Squeal,”, 20.

- ^ “Everything but the Squeal,”, 19; Harva Hachten and Terese Allen, The Flavor of Wisconsin: An Informal History of Food and Eating in the Badger State, 2nd ed. (Madison, WI Wisconsin Historical Society, 2009), 79.

- ^ Crocker Stephenson, “Peck Remembered for Philanthropy, Service—and Clowning,” JSOnline, October 9, 2015; “Saving Emmpak Foods from Slaughter,” Milwaukee Business Journal, July 15, 2001; David Schuyler, “Cargill Closing Milwaukee Slaughterhouse, Cutting 600 Jobs,” Milwaukee Business Journal, July 30, 2014; Sean Ryan, “Potawatomi Tribe Buys Shuttered Cargill Meat Plant Near Potawatomi Hotel and Casino,” Milwaukee Business Journal, May 21, 2015.

- ^ Eric Brooks, “Stockyards to Close Local Site, Move to Dodge County,” Milwaukee Business Journal, September 12, 2004.

- ^ Patrick Cudahy, Inc., Celebrating 110 Years of Goodness: Patrick Cudahy, 1888-1998 (Cudahy, WI: Patrick Cudahy, 1998), 8, 11-12, 14-15; Jeff Engel, “Patrick Cudahy Won’t Change Much Under New Chinese Parent Company,” Milwaukee Business Journal, October 3, 2013.

- ^ Roger A. Stafford, “Weisel Keeps the Faith,” Milwaukee Sentinel, November 18, 1974, sec. 2, p. 13.

- ^ Stafford, “Weisel Keeps the Faith.”

- ^ “Weisel Sausage Co. Sold,” Milwaukee Sentinel, November 22, 1977, sec. 4, p. 2; Gordon L. Randolph, “Century Old Weisel Sausage Closed,” Milwaukee Journal, June 1, 1979, sec. 2, p. 15.

- ^ Hachten and Allen, The Flavor of Wisconsin, 76-77.

- ^ “Frederick Layton Is Dead—All City Mourns Loss,” 1.

- ^ Bayrd Still, Milwaukee: The History of a City (Madison, WI: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1948), 347; Gregory, History of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, 1:500; Jeff Beutner, “Yesterday’s Milwaukee: Milwaukee Industrial Exposition Building, 1880s,” Urban Milwaukee, August 18, 2015.

- ^ Gregory, History of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, 1:544; “In Memoriam: Philanthropist and UWM Benefactor Bernard Peck,” UWM Report, October 22, 2015.

For Further Reading

Geib, Paul E. “‘Everything but the Squeal’: The Milwaukee Stockyards and Meat-Packing Industry, 1840-1930.” The Wisconsin Magazine of History 78, no. 1 (Autumn 1994): 2-23.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.