Europeans derived Lake Michigan’s name from the Anishinaabemowin word mishigami, meaning “big lake.” It is the second largest Great Lake by volume and third by area surface; it is the only one located entirely within the United States.[1] Milwaukee’s economic development has been made possible by the Lake’s harbor, which provided protection from storms and ease of transportation, and the three rivers—the Kinnickinnic, Menomonee, and Milwaukee—that flow through the city into the lake. Scholars believe that Menominee, Ho-Chunk, Sauk, Fox, and Mascouten were present in the region as early as the 1200s-1400s. An estimated 60,000 to 117,000 Indigenous peoples lived in the Great Lakes region at the time of European contact (the first half of the sixteenth century on the eastern Great Lakes, the 1620s in what is now Wisconsin). For all the peoples who have lived near its shores, Lake Michigan has provided power, subsistence, transportation, and recreation. It has been, as John Gurda writes, “indisputably a maker of place.”[2]

The Rise and Fall of Commercial Fishing

The Indigenous people developed a way of life based around water and seasonal fishing, which was echoed later in Milwaukee’s development as a city.[3] The Lake Michigan shore drew Indigenous peoples to the shoreline during the summer, while in the winter, they lived in more sheltered regions. Warfare between Europeans and native peoples and among native tribes in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries completely wiped out some Indigenous groups and scattered others throughout the Midwest.[4]

Just as fishing provided a stable food supply for the Indigenous peoples who settled in what became Milwaukee, fishing in Lake Michigan provided Wisconsin with its first commercial enterprise in the 1830s. The enterprise was supported first by independent fishermen and later through networks of local white and Indigenous fishermen as a supplement to the region’s fur trading. These networks provided the fish for packing in the Eastern markets. Fishing continued to be one of the dominant industries throughout the nineteenth century, although after the 1880s, production levels declined due to overfishing, pollution, and depressed markets in the United States.[5]

Lake Michigan has been a depository for much of Milwaukee’s water waste since the city’s founding, while it also served as the city’s primary source of fresh water. Starting in 1846, when Milwaukee was incorporated, a crude water system was developed that relied on carts to haul water from Lake Michigan or one of the rivers. However, this method was not enough to sustain the needs of the growing city. In 1871 construction began on a water pump and storage system—the North Point Water Tower and the North Point Pumping Station. It opened in 1874.[6] Although the system provided the city with fresh water, the city struggled with wastewater management throughout the nineteenth century.

In the 1880s, Milwaukee built waste and storm sewers that diverted water directly into Lake Michigan, as unchecked population growth made Milwaukee’s ground water undrinkable and largely unusable. A sewer system was built in the late 1860s. The new pipes intercepted the waste and diverted it to a waste treatment plant before being pumped into Lake Michigan, which constantly cycled filthy water between the rivers. This system was intended to solve the waste and wastewater disposal problems of the city but did little to address the pollution of the rivers.[7] Additionally, in the late 1800s, Milwaukee also began dumping its garbage in the lake.[8] This practice eventually polluted the rivers that flow through Milwaukee so much that flushing tunnels were built to circulate water from Lake Michigan into the sewage system. The flushing system, where filthy river water was flushed with fresh lake water, was created in the 1880s. As John Gurda notes, the city replaced one problem, a polluted river, with another, a polluted lake. In 1925 a centralized treatment plant was built on Jones Island at the mouth of the Milwaukee River to address the pollution.[9]

These measures did not prevent overflow sewage during rainstorms, which continued to pollute the waterways and lake, making it impossible to sustain the fishing industry in the late nineteenth century. Fishing rebounded during the 1910s and 1920s, when commercial fishermen on Lake Michigan hauled in an average of 41 million pounds of fish annually. In 1938, Wisconsin’s commercial fishing was motorized. Despite overfishing and emerging ecological issues brought on by Milwaukee’s continuing use of the lake for waste and garbage disposal, fisherman still managed to net an annual average of 14 million pounds of fish.[10]

Milwaukee’s Jones Island was not only a water treatment plant, but also a fishing hub, a village built around fishing and populated by German and Kashubian (an ethnic group closely related to the Poles) immigrants.[11] Catching rainbow smelt, one of Lake Michigan’s original invasive species, became an annual tradition for families that fished along Jones Island and the flushing tunnel on Lincoln Memorial Drive.[12] During the early to mid-1900s, smelt fishing provided seasonal recreation for some and sustenance for others. “Smeltmania,” as it was referred to in the Stevens Point Daily Journal, reached its cultural zenith in the 1930s, when dances, banquets, and parades were held throughout the state to celebrate smelt and fishing. Beginning in the early 1990, the smelt population began to decline, victims of new invasive species and pollution, which contributed to the overall decline in Lake Michigan fishing during this period.[13]

Indeed, throughout the twentieth century, Lake Michigan was plagued by ecological problems that diminished Milwaukee and Wisconsin’s fishing industries. Lamprey, a non-native predator, and constant commercial fishing devastated the local whitefish and trout populations by the mid-twentieth century. In the late 1950s and into the 1960s, millions of alewives, a type of herring that was not native to Lake Michigan, died near shore. To combat the alewife infestation, salmon were brought in, which created a “salmon boom.” Chinook and Coho salmon were stocked from the 1960s through 1980s to control alewives and to maintain the commercial fishing industry. The importation of salmon reached its peak in the 1980s, with 8 million salmon planted in the lake. However, in the 1990s, chinook salmon began dying of bacterial kidney diseases brought about by a decline in alewives, causing the catch to plummet to just 15 percent of what it was in the mid-1980s.[14] Additional invasive species, believed to have been brought to the Great Lakes by ocean-going freighters, continue to affect Lake Michigan’s fishing industry. Since the early twenty-first century, invasive quagga mussels, a cousin to the already present invasive zebra mussels, have dramatically changed the food web that sustained the lake’s native fish.[15]

The ecological crises facing the lake in the early 1970s played a role in key lawsuits that aimed to protect the environment of waterways in the United States. The People of the State of Illinois v. the City of Milwaukee and Its Sewerage Commission (1972) alleged that Milwaukee allowed the discharge of raw, untreated sewage into the lake, continuing a practice established during the late 1800s. Milwaukee’s actions were “causing serious and substantial deterioration” in the quality of Lake Michigan’s waters within the territorial boundaries of the State of Illinois.[16] The court ruled that it was Milwaukee’s responsibility to clean the lake, since pathogenic organisms and contaminants entered Lake Michigan via Milwaukee and negatively impacted individuals in Illinois. In 1977, judges prohibited any further water waste dumping in Lake Michigan except during the severest storms. This ruling prompted several changes to the sewage system—including the building of Milwaukee’s “deep tunnel” system—in the 1980s and 1990s.[17]

The early twenty-first century saw continued efforts to clean up Lake Michigan and its three largest tributaries, the Kinnickinnic, Menomonee, and Milwaukee Rivers.[18] In 1987 the Milwaukee Estuary was designated an “Area of Concern” (AOC) by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) under the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement. PCBs (polychlorinated biphenyls, widely used in electrical equipment), PAHs (polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, released during the burning of coal, oil, gasoline, trash, tobacco, and wood), and heavy metals, the primary contaminants in the Milwaukee Estuary AOC, were a result of previous industrial discharges, the city’s history of improper wastewater disposal, sewage overflows, and agricultural and urban runoff. The contaminants restricted fish and wildlife consumption by humans.[19] Milwaukee received $14.3 million from the EPA to clean up waterways after algae blooms were found in the lake and rivers in the 1990s and early 2000s; the entire project cost $22 million. Milwaukee also became an “Innovating City” in the United Nations’ Global Compact Cities Programme and formed the Milwaukee Water Council in 2009 with the intention of not just treating water quality as a single issue but to address the political, economic, and cultural contexts of pollution.[20] Using this approach, Milwaukee’s Metropolitan Sewerage District won the 2012 United States Water Prize from the US Water Alliance, a clean water advocacy group.[21]

Transportation and the Development of Milwaukee

As the primary mode of transportation for commerce and people in the early years of the city’s settlement, Lake Michigan helped Milwaukee rise to national prominence in subsequent decades. The rivers, streams, and lake were originally used by fur traders in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The significance of Milwaukee’s port grew in the decades after its opening in 1835, as settlers and traders took advantage of the eastern water access through the lake and the rivers. Maritime commerce and the supporting industries encouraged Milwaukee’s growth as a port city.[22]

The first cargo pier was built near the current Discovery World Museum in 1843, although for a number of years Milwaukee’s lakefront was largely ignored in favor of the river. However, the natural sandbar at the mouth of the Menomonee River impeded traffic in and out of Milwaukee’s harbor. Jones Island, originally a small peninsula near the confluence of the Milwaukee and Menomonee Rivers, became an “island” when a “straight cut” was made to the lake to allow larger ships to enter the city’s inner harbor.[23] By the end of the nineteenth century, Mayor David S. Rose recommended construction of the docks and terminals outside of Jones Island, as the rivers had proven inadequate to meet the increasing demand of Milwaukee’s commerce. Construction on the Outer Harbor began in August 1914. The municipal Board of Harbor Commissioners took over harbor operations in 1920.[24] Since the beginning of Milwaukee through its industrial heyday in the 1950s, Lake Michigan was the primary outlet for the exporting of people and of the products of Milwaukee’s many mills, foundries, and tanneries, as well as the lumber, grain, and other items produced in the state’s hinterlands.[25]

Railroads were integrated into Lake Michigan shipping by late in the nineteenth century. Car ferries transported railroad cars, freight, and passengers across the lake between Michigan and Wisconsin through the Port of Milwaukee. Prior to the Second World War, there were fifteen different ferry routes across Lake Michigan. They were centralized after the war into seven routes run by three railroads: Ann Arbor Railroad, Grand Trunk Western, and the Pere Marquette, which became part of the Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad company in 1947.[26] At the height of carferry use in 1955, 205,000 individuals travelled by lake and 204,460 freight cars were carried across Lake Michigan in 6,986 crossings. However, the Grand Trunk Milwaukee Ferry Company ceased its Muskegon, Michigan, to Milwaukee route in 1978, and in 1979 the Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad ceased operations to Milwaukee. Despite no longer carrying railroad freight cars, passenger service across the lake continued. Milwaukee’s current car ferry, the Lake Express, was established in 2004. It makes the voyage between Milwaukee and Muskegon in two and a half hours.[27]

The lakefront also provided space for early air travel and Cold War defense. Maitland Field, which opened in 1927, was a small general aviation airport. Most air traffic came in and out of the county-owned airport a few miles south (now Milwaukee Mitchell International Airport), and the field was turned over to the Army in the mid-1950s as a Nike missiles site.[28] In the late 1960s, after the missiles were made obsolete, the site was given back to the City of Milwaukee. Summerfest, Milwaukee’s premier music festival, started by Mayor Henry Maier, moved into the abandoned lakefront Nike Missile site in the summer of 1970.[29]

Lake Michigan as Recreational Space

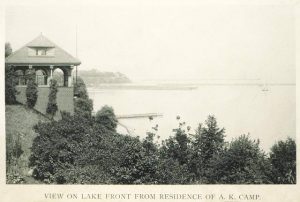

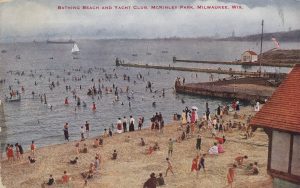

Summerfest was the latest in a long history of lakefront recreation in Milwaukee. Just as the lake has always been a primary resource for food and drinking water, transportation of people and goods, and a place for waste disposal, the lake also became a site of recreation during the city’s early days. Milwaukee’s county parks, beaches, museums, and numerous summer events have long been a feature of the lakeshore. In the summer, people flocked to the lake. Boys and girls fished or swam while men and women sailed. Boating and yachting were very popular in the late 1800s, an echo of a national trend that focused on health and leisure. In 1871 the Milwaukee Yacht Club was established near downtown, while the Pine Lake Yacht Club catered to wealthy German-Americans in Lake Country.[30]

Throughout the United States during the nineteenth century, there was a movement to recapture natural beauty. Parks were believed to be “gardens of the poor” that could offer “the joys of natural beauty” to those who did not have their own home gardens.[31] Milwaukee was part of that movement. By converting much of the Lake Michigan shoreline into a park system, Milwaukeeans celebrated Lake Michigan by preserving access for its citizens.[32]

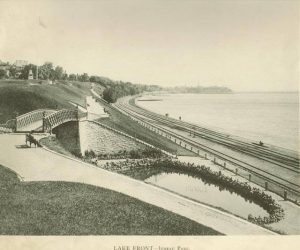

One of the oldest parks, Lake Park, began in 1849 as Lueddemann’s-on-the-Lake, a resort, picnic, and recreation area that occupied the north section of current Lake Park.[33] In 1889, Milwaukee created the City Park Commission and began purchasing lakefront real estate (the City Park Commission merged with the County Park Commission in 1936). Once the land was acquired, the Park Commission contracted Frederick Law Olmsted to design Lake Park. Construction was completed in the following decade. Olmstead, who also designed River Park (now Riverside) and West Park (now Washington Park), intended to take advantage of Lake Michigan’s natural beauty to be “morally restorative to the city dweller” and provide both “active” and “passive” recreation.[34] Between the 1890s and 1930s, major buildings, walking paths, bridges, and pavilion spaces were built to celebrate Lake Park and the lakefront. Milwaukee’s transportation and recreation systems worked together when the Milwaukee Electric Railway and Light Company built a tram station in 1903 to welcome visitors to the park.[35]

The City of Milwaukee transferred the park land to Milwaukee County during the 1930s. Since the transition of ownership, bowling greens, club houses, ice-skating rinks, baseball and soccer fields, and a bicycle path have been built. The 1855 North Point Lighthouse, a symbol of the city’s close connection to the lake, was decommissioned in 1994. It was transferred to Milwaukee County in 2003 and added to Lake Park. The lighthouse was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1984. In 2007, the lighthouse opened to the public as a maritime museum and conference center.[36]

Seventh Ward Park was originally the largest public green space in Milwaukee when it opened on the bluffs above the lake at Juneau Avenue and Mason Street in the late 1880s. It was renamed for Milwaukee pioneer Solomon Juneau in 1957. The park features a replica of Juneau’s cabin, as well as monuments to Juneau and Leif Ericson (both erected in 1887).[37]

Boating continued to be a major element in the city’s relationship to Lake Michigan following the Second World War. The Park Commission began building a public marina in 1963 and extended the existing south shoreline of the Juneau Park lagoon into Lake Michigan by filling the area with fill and rubble. The landfill, which includes what was once the Juneau lagoon, eventually became Veterans Park in 1979. McKinley Marina, which opened in the 1980s, provides 655 boat slips.[38] Veterans Park is also home to the War Memorial Center and the Milwaukee Art Museum, whose distinctive Calatrava addition has come to symbolize Milwaukee.[39]

Lake Michigan has been an integral part of Milwaukee’s economy and culture—in fact, its identity—throughout its history. As John Gurda writes, “the city has been made, remade, and remade again” and the city’s landmarks are “vivid reminders of the community’s heritage as a city built on water.”[40] The lake is fundamental to the city and, as Milwaukee residents know, it really is “cooler near the lake.”

Footnotes [+]

- ^ US Environmental Protection Agency, “Geophysical Lake Michigan,” last updated September 2016, accessed June 4, 2018; US Environmental Protection Agency, “Physical Features of the Great Lakes,” last updated September 2016, accessed May 10, 2019.

- ^ “Areas and Volumes of the Great Lakes,” Encyclopedia Britannica, accessed July 26, 2019; John Gurda, Milwaukee: A City Built on Water (Madison, WI: Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 2018) 1-3.

- ^ Randall Schaetzl, “Native Americans in the Great Lakes Region,” Michigan State University, accessed May 10, 2019.

- ^ “Indian Country: Great Lakes History: A General View,” Milwaukee Public Museum, accessed May 20, 2019); Schaetzl, “Native Americans in the Great Lakes Region,” accessed May 10, 2019.

- ^ “Fishing Industry in Wisconsin,” Wisconsin Historical Society, accessed May 10, 2019.

- ^ John Gurda, The Making of Milwaukee (Milwaukee: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 1999) , 130-135.

- ^ Gurda, The Making of Milwaukee, 144-145.

- ^ Gurda, Milwaukee: A City Built on Water, 203.

- ^ Gurda, Milwaukee: A City Built on Water, 146.

- ^ Dan Egan, “‘The Lake Left Me. It’s Gone,’” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, August 13, 2011, accessed July 19, 2019.

- ^ Egan, “‘The Lake Left Me,” accessed May 10, 2019; “Fishing Industry in Wisconsin,” accessed May 10, 2019.

- ^ Gurda, Milwaukee: A City Built on Water, 178.

- ^ Paul A. Smith, “Smelt Fishing Enjoys Revival on Lake Michigan,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, April 14, 2017, accessed May 10, 2019; Keith Matheny, “Smeltdown: Small Fish Continues Great Lakes Vanishing Act,” Detroit Free Press, April 4, 2015, accessed July 19, 2019.

- ^ Gurda, The Making of Milwaukee, 357; Dan Egan, “Salmon Crowned King, but Its Reign Is Wobbly,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, accessed May 10, 2019.

- ^ Egan, “‘The Lake Left Me,’” accessed May 10, 2019; Egan, “Salmon Crowned King,” accessed July 26, 2019.

- ^ Clifford H. Mortimer, Lake Michigan in Motion: Responses of an Inland Sea to Weather, Earth-Spin, and Human Activities (Madison, WI: The University of Wisconsin Press, 2004), 272.

- ^ Mortimer, Lake Michigan in Motion, 276.

- ^ Paul Thomas Ferguson, “Leisure Pursuits in Ethnic Milwaukee, 1830-1930” (Ph.D. diss., Marquette University, 2005), 177.

- ^ “About Milwaukee Estuary AOC,” Environmental Protection Agency, last updated September 2016, accessed May 10, 2019.

- ^ “Kinnickinnic River Legacy Act Dredging Project,” United States Environmental Protection Agency, accessed July 12, 2019.

- ^ “2019 Operations and Maintenance and Capital Budgets,” Milwaukee Metropolitan Sewerage District, accessed July 12, 2019.

- ^ “A History of Port Milwaukee,” City of Milwaukee, last accessed August 30, 2019.

- ^ Gurda, Milwaukee: A City Built on Water, 26-29; Jeff Beutner, “Yesterday’s Milwaukee: Jones Island Fishing Village, 1898,” Urban Milwaukee, April 13, 2016, accessed May 10, 2019.

- ^ Jeff Beutner, “Yesterday’s Milwaukee: Sailing Vessels and Steamers, 1860s,” Urban Milwaukee, October 4, 2016, accessed May 10, 2019; “A History of Port Milwaukee,” accessed July 26, 2019.

- ^ “Shipbuilding in Wisconsin,” Wisconsin Historical Society, accessed May 10, 2019; “Milwaukee Shipyard, Milwaukee WI,” ShipBuildingHistory.com, last updated May 9, 2016, accessed May 10, 2019; Gurda, Milwaukee: A City Built on Water, 44.

- ^ John Kelly, “Lake Michigan Carferries,” Classic Trains magazine, available through Internet Archive, https://web.archive.org/web/20060104111452/http://www.trains.com/Content/Dynamic/Articles/000/000/001/366uebbl.asp, accessed May 10, 2019.

- ^ Leah Dobkin, Soul of a Port: The History and Evolution of the Port of Milwaukee (Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2010), 64-66; Paul Trapp, “Rails across the Water,” Michigan History Online, available through the Internet Archive, https://web.archive.org/web/20060513210549/http://www.michiganhistorymagazine.com/extra/transportation/rails/rails_across_water.html, accessed May 10, 2019.

- ^ Paul Freeman, “Southeastern Wisconsin,” Abandoned and Little Known Airfields website, last updated April 2018, accessed May 10, 2019.

- ^ Gurda, The Making of Milwaukee, 325, 402; Danny Benson, “Summerfest: Cold War Battleground,” July 7, 2013, last accessed August 30, 2019.

- ^ Ferguson, “Leisure Pursuits in Ethnic Milwaukee,” 174-76.

- ^ Dolores Knopfelmacher, “History,” Lake Park Friends, last accessed August 30, 2019.

- ^ Jeff Beutner, “Yesterday’s Milwaukee: The Lakefront, about 1866,” Urban Milwaukee, March 31, 2015, last accessed August 30, 2019.

- ^ Ferguson, “Leisure Pursuits in Ethnic Milwaukee,” 258. Knopfelmacher, “History,” last accessed August 30, 2019.

- ^ Knopfelmacher “History,” last accessed August 30, 2019.

- ^ Knopfelmacher “History,” accessed May 10, 2019.

- ^ Laurie Muench Albano, Milwaukee County Parks (Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2007), 16; Park Directory and Index of Facilities, “Juneau Park,” Milwaukee County Park Commission (1972), http://county.milwaukee.gov/HistoryoftheParks16572.htm, accessed May 10, 2019, available through the Internet Archive, https://web.archive.org/web/20180316202920/http://county.milwaukee.gov/HistoryoftheParks16572.htm, accessed August 30, 2019; “Discovering New Secrets beneath Juneau Park in Downtown Milwaukee,” The Distant Mirror June 3, 2011, accessed May 10, 2019.

- ^ Albano, Milwaukee County Parks, 119-120; Gurda, Milwaukee: A City Built on Water, 100-103.

- ^ Don Behm, “Milwaukee Art Museum to Acquire O’Donnell Park in Deal Valued at $28.8 Million,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, March 8, 2016, accessed May 10, 2019.

- ^ Gurda, Milwaukee: A City Built on Water, 210-11.

For Further Reading

Albano, Laurie Muench. Milwaukee County Parks. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2007.

Annin, Peter. The Great Lakes Water Wars, revised and updated. Washington, D.C.: Island Press, 2018.

Dobkin, Leah. Soul of a Port: The History and Evolution of the Port of Milwaukee. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2010.

Egan, Dan. The Death and Life of the Great Lakes. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company, 2017.

Gurda, John. Milwaukee: A City Built on Water. Madison, WI: Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 2018.

Kriehn, Ruth. The Fisherfolk of Jones Island. Milwaukee: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 1998.

Mortimer, Clifford H. Lake Michigan in Motion: Responses of an Inland Sea to Weather, Earth-Spin, and Human Activities. Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press, 2004.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.