Pollution—of the water, air, and land—is an unfortunate but constant feature of Milwaukee’s history. Much of the city’s pollution has been the result of commerce and industry. However, the growth in Milwaukee’s population also contributed to the problem, particularly in terms of contamination from sewage and wastewater. While the worst of Milwaukee’s pollution problems seem to be in the past, the city still feels the effects of contamination of the water, air, and land from earlier generations.

Given the importance of water in Milwaukee’s foundation and growth, it is not surprising that the earliest and most significant form of pollution in the city was found in the city’s waterways. While the early days of European settlement in the area did little in the way of directly fouling the local waters, the transformation of the land from swamp to dry ground primed the rivers and lake for future pollution problems by removing many of the natural defenses against such contamination.[1]

In the decades after the Civil War, the continued growth of Milwaukee’s population was devastating to the city’s water quality. During this time, most citizens got their drinking water via wells and used outhouses with privy vaults to dispose of wastewater. With the rise in population, privies began to contaminate the groundwater so much that well water in most areas of the city became unsafe.[2] The city began work on a sewage system in 1869, but this only diverted raw sewage into the city’s rivers. The Milwaukee and Kinnickinnic rivers became little more than open sewers.[3] Most of the many tons of animal feces left on city streets during this era of horse-drawn transportation also ended up in the rivers when it mixed with rain to form what one historian called “streams of liquid filth” running into the city’s waterways.[4]

In 1880 the city attempted to clean up its rivers by creating a system of pipes that led liquid waste to a pumping station on Jones Island that pumped it far out into Lake Michigan. Yet this did little to ameliorate the problem on the rivers, as pollution was also coming from the various heavy industries that now dominated most of the city’s riverfront.[5]

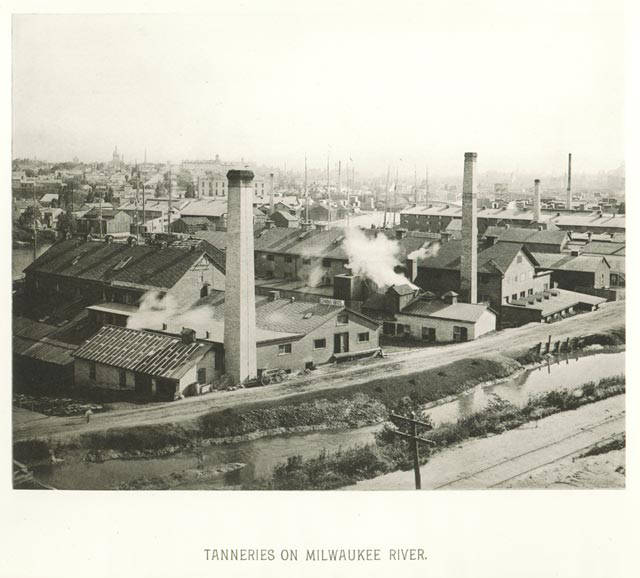

Perhaps the most revolting industrial runoff into the rivers was from the city’s numerous tanneries and stockyards. The Milwaukee Stockyards opened in the Menomonee Valley in 1869 and were soon processing thousands of animals every day.[6] Blood, viscera, and manure ran off into the Menomonee River in startling quantities, turning the water into a stinking, “sluggish” mass.[7] An 1878 Health Commission report found that more than 100 tons of excrement were washed from the stockyards into the river every day.[8]

The city’s tanneries, located primarily on the Milwaukee and Menomonee rivers, needed the rivers as a source of water and as a shipping line for their finished products, but also used them as a means of disposal for the chemical mixture used in the tanning process. This run-off, while it was treated with lime water and antiseptic bark juice, further contributed to river pollution.[9] River water was also used to rinse tanned hides, washing a significant amount of hair and animal flesh into the water.[10]

The huge amount of coal being consumed by factories and steam-powered trains and ships also put immense amounts of impurities in the air. According to historian John Gurda, coal-burning had by the 1880s created a “permanent pall of smoke” over the city’s freight yards and factory districts.[11] The ground was also being polluted with chemical and manure run-off and contamination. In some cases, ground was literally being made entirely from pollutants and garbage. “Free dumps” were used in the Menomonee Valley to fill marshy land, encouraging the contribution of rotten food, animal entrails, and all matters of filth and trash by residents. This “fill” would then be covered with dirt and treated as natural ground.[12]

In 1888, the city completed its most intensive effort to date to combat river pollution. The world’s largest pump (a coffee shop took over the flushing station built over the pump in the early twenty-first century) drew water from Lake Michigan and forced it through underground pipes to a point on the Milwaukee River just north of downtown. A similar pump was later installed on the Kinnickinnic River. These plumes of fresh lake water helped to flush stagnant pollution from the rivers but also caused most of the filth to end up in Lake Michigan, the source of Milwaukee’s drinking water. The result was a series of outbreaks of “intestinal flu” and other ailments from people drinking contaminated lake water.[13]

In addition to estimated 55 million gallons of sewage being pumped into the lake every day by 1896,[14] and the filth washed out from the rivers, Lake Michigan was also being used as a garbage dump. Before the completion of the city trash incineration plant in 1902 (which would have still contributed to air pollution), much of the city’s trash was either burned, buried, or dumped into the lake.[15]

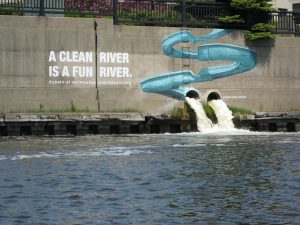

In 1909, the state finally forced the city to take its first steps toward solving water contamination. A special commission appointed by the city recommended that a system be developed to thoroughly treat sewage and a filtration method for all lake water drawn into the city water works.[16] Because of the immense cost of each of these ventures, the city was slow in adopting the commission’s recommendations. The Sewerage Commission of the city of Milwaukee was established in 1913 to modernize the sewage treatment process, but it was not until 1926 that the treatment facility they designed went into service.[17] This facility, located on the north end of Jones Island, is still used today. The water filtration system did not go online until 1939. Despite these reforms, damage done to the river ways caused serious water quality issues into the 1970s.[18]

Despite the relatively early awareness of waterway and lake pollution, it was not until the 1950s that Milwaukee County began to monitor and regulate air pollution. By the early 1960s, the county reported that solid air pollutants—such as fly ash and soot—had dropped to their lowest levels since monitoring began. The drop was credited to the installation of filtration systems on many factory smokestacks as well as a reduced dependence on coal, a long-time contributor to air pollution. Through the 1960s, heating and electrical generation from coal burning had decreased, as had the number of steam-powered trains passing through the city.[19]

Federal regulations in the 1960s and 1970s mandated that the city take even greater action against water and air pollution. The 1967 Clean Air Act forced the city to begin addressing ground-level ozone air pollution as well as large-particle solid pollutants. Over the course of several years, the city began switching its power plants away from pulverized coal, and the state offered tax credits to factories that took action to reduce smoke output.[20] Federal laws in 1972 and 1977 compelled the city to improve its sewage district and address river water quality.[21]

The true legacy of Milwaukee’s industrial ground pollution has only come to light in recent years, as the land once occupied by factories and plants is now assessed for redevelopment. There are presently two partially remediated “Superfund” sites in Milwaukee County, each with land and water badly contaminated by industrial runoff and improper disposal of waste, that, according to the Environmental Protection Agency, pose a danger to public health and safety. One is the former burial site of hundreds of drums of industrial chemicals (6800 S. 27th Street); the other is the site of the former Moss-American Oil Company (8716 Granville Road).[22] Ozaukee and Washington counties each have one superfund site and Waukesha County is home to four, each of which are former landfill sites that now have dangerous levels of ground and surface water pollution.[23]

Although improvements have been made in the regulation and tracking of pollution in the region, problems still persist. Although water quality in the river is higher than it has been in a century, contamination from road salt wash-off has been increasing, as are nitrites from fertilizer and leaking septic systems.[24] As recently as 2012, the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources issued a total of 20 particle and ozone pollution warnings, meaning air quality in the area could potentially be harmful to older adults and children.[25] Milwaukee area residents are required to use reformulated gasoline as a means of reducing ground-level ozone pollution, a mandate that was written into the 1990 Clean Air Act and cannot be undone unless by an act of Congress.[26] The number of superfund sites in the area, as well as the number of brownfield remediation sites that need to be cleaned up before the land can be developed, also show that, while the area has made great strides in fighting pollution, the legacy of industrial abuse of the land, water, and air in the Milwaukee area is far from over.

Footnotes [+]

- ^ Milwaukee River Revitalization Council, An Historical Overview of the Milwaukee River Basin (Milwaukee: Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, 1989), 5. This entry was originally posted on April 23, 2019 and was updated on September 15, 2021.

- ^ Milwaukee Health Department, Annual Report of the Commission of Health of Milwaukee for the Year of 1879, 244.

- ^ John Gurda, The Making of Milwaukee (Milwaukee: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 1999), 144-146.

- ^ Bayrd Still, Milwaukee: The History of a City (Madison, WI: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1965), 241.

- ^ Gurda, Making of Milwaukee, 144-146.

- ^ Paul Geib, “‘Everything but the Squeal’: The Milwaukee Stockyards and Meat-packing Industry, 1840-1930,” Wisconsin Magazine of History 78 no. 1 (Autumn, 1994), 5.

- ^ Milwaukee Health Department, Annual Report of the Commission of Health of Milwaukee for the Year of 1878, 162, 167.

- ^ Milwaukee Health Department, Annual Report of the Commission of Health of Milwaukee for the Year of 1878, 94-95.

- ^ Milwaukee Health Department, Annual Report of the Commission of Health of Milwaukee for the Year of 1878, 156.

- ^ H.M. Heisig and James Brower, “Practices of Industrial Waste Disposition at Milwaukee,” Sewage Works Journal 4, no 4. (July 1932), 682.

- ^ Gurda, Making of Milwaukee, 88.

- ^ JJohn Gurda, “The Menomonee Valley: A Historical Overview,” Renew the Valley website, accessed February 20, 2015, http://www.renewthevalley.org/media/mediafile_attachments/04/4-gurdavalleyhistory.pdf; now available at https://web.archive.org/web/20151001215044/http://www.renewthevalley.org/media/mediafile_attachments/04/4-gurdavalleyhistory.pdf, accessed September 15, 2021.

- ^ Gurda, Making of Milwaukee, 144-146.

- ^ Milwaukee Health Department, Annual Report of the Commission of Health of Milwaukee for the Year of 1897, 29.

- ^ Gurda, Making of Milwaukee, 202.

- ^ T. Chalkley Hatton, “Milwaukee Sewage Disposal Problem,” Proceedings of the Eighteenth Annual Convention of the League of American Municipalities (1915): 39.

- ^ “History,” Milwaukee Metro Sewage District website, accessed May 23, 2015.

- ^ Milwaukee River Revitalization Council, Historical Overview of the Milwaukee River Basin, 11.

- ^ “Tests Show County Has Cleaner Air,” Milwaukee Journal, January 22, 1961, part 2, p. 1.

- ^ “State Gets Organized for War on Pollution,” Milwaukee Journal, February 19, 1969, p. 1; “First Year Record on Air Pollution Control ‘Fair,’” Milwaukee Journal, July 25, 1969, p. 1.

- ^ “History,” Milwaukee Metro Sewage District website, accessed May 23, 2015.

- ^ “Milwaukee Toxic Sites and Pollution Sources,” Milwaukee Green Map website, http://www.wisconline.com/greenmap/milwaukee/sites/toxic.html, accessed June 1, 2015; now available at https://web.archive.org/web/20150906161145/http://www.wisconline.com/greenmap/milwaukee/sites/toxic.html, accessed September 15, 2021.

- ^ “Rank Superfund Sites, Wisconsin,” Scorecard: The Pollution Information website, http://scorecard.goodguide.com/env-releases/land/rank-sites.tcl?fips_state_code=55, accessed June 3, 2015, now available at https://web.archive.org/web/20150930071725/http://scorecard.goodguide.com/env-releases/land/rank-sites.tcl?fips_state_code=55, accessed September 15, 2021.

- ^ Lee Berquist and Kevin Crowe, “Urban, Rural Runoff Remains Pollution Problem for Rivers Today,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, June 9, 2014.

- ^ “Milwaukee Air Quality Notice History,” Wisconsin DNR website, updated and accessed June 13, 2015.

- ^ Lee Berquist and Joe Taschler, “Reformulated Gasoline Is Adding to Pump Price Woes,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, March 31, 2012.

For Further Reading

Geib, Paul. “‘Everything but the Squeal’: The Milwaukee Stockyards and Meat-packing Industry, 1840-1930.” Wisconsin Magazine of History 78 no. 1 (Autumn 1994): 2-23.

Hatton, T. Chalkley. “Milwaukee Sewage Disposal Problem.” Proceedings of the Eighteenth Annual Convention of the League of American Municipalities (1915): 33-45.

Heisig, H.M., and James Brower. “Practices of Industrial Waste Disposition at Milwaukee.” Sewage Works Journal 4, no 4. (July 1932): 680-685.

Milwaukee River Revitalization Council. An Historical Overview of the Milwaukee River Basin. Milwaukee: Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, 1989.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.