Flour milling became Milwaukee’s first manufacturing industry of note during the middle and late nineteenth century. The city’s first flour mill opened in 1844, and the rate of production increased steadily throughout the 1840s and 1850s as additional mills began operation.[1] Despite steady growth, however, Milwaukee’s flour industry experienced its largest boom after 1870. Prior to that, most milling in Wisconsin was done in small facilities that served local markets and were scattered around the state. After the Civil War, the volume of grain production in Wisconsin, Minnesota, and northern Iowa increased; in addition, technological advances led to a rapid centralization of milling in urban centers such as Milwaukee. The Cream City was ideally suited to that purpose. Early milling required water power, and the Milwaukee River, having been dammed as part of the failed Rock River Canal Project in the 1840s, provided ample hydraulic energy. Milwaukee was also perfectly situated to receive large shipments of wheat pouring in from the north and west, process it, and shuttle the resulting flour to the eastern seaboard via Great Lakes shipping routes or rail lines. (A barrel of flour required around five bushels of wheat.)[2]

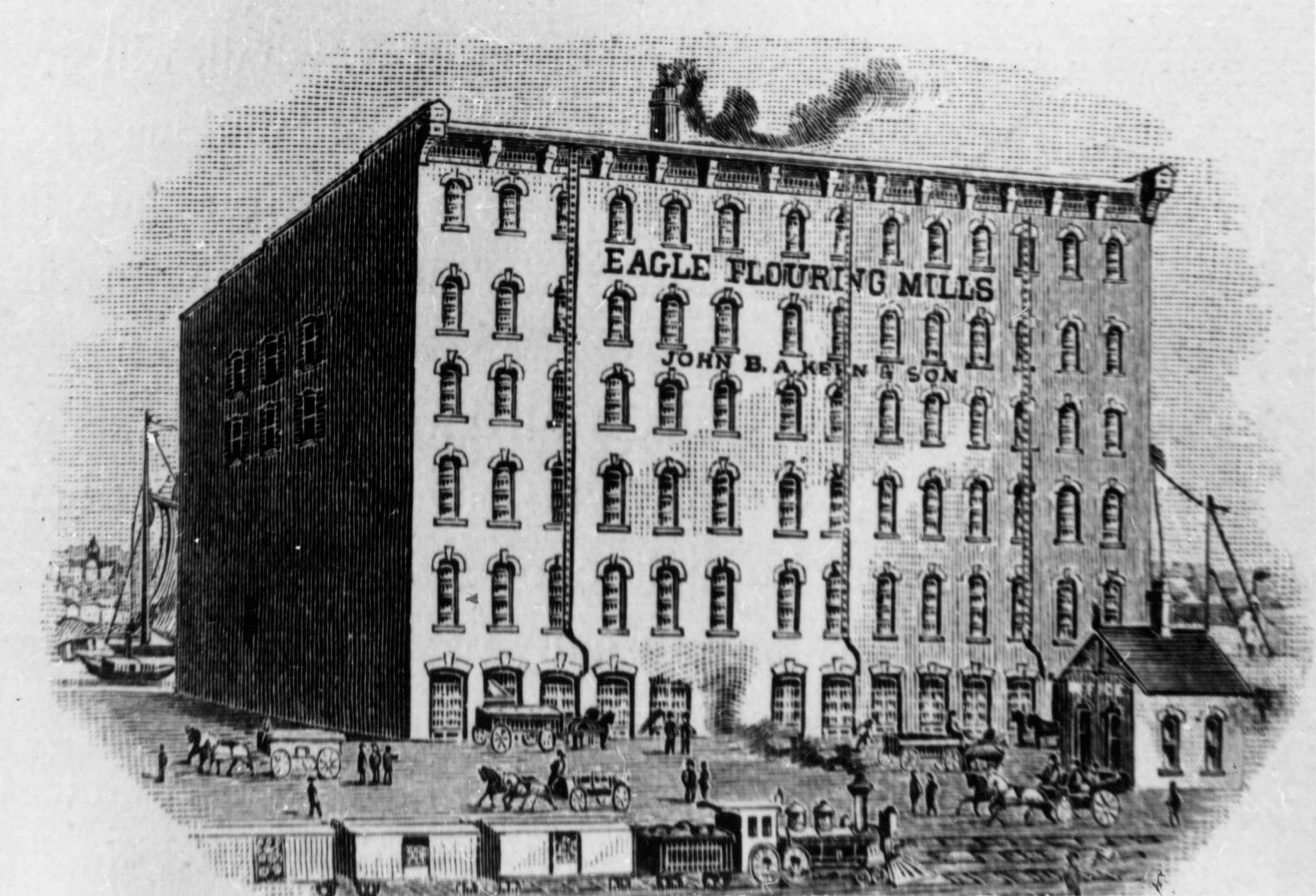

Flour milling was considered a reputable occupation and the largely German milling community was esteemed among the city’s businessmen. Milwaukee’s central flour milling district was located along the Milwaukee River, just below the North Avenue dam, with the two largest mills situated along the west bank of the river near present-day Vliet Street. By the early 1890s, there were seven major mills operating in the city: Eagle, Phoenix, Daisy, Reliance, Jupiter, Duluth, and Gem.[3] Other flour production centers in the state included Neenah-Menasha, Watertown, Janesville, Appleton, Oshkosh, Fond du Lac, and LaCrosse; however, none of these towns could offer access to national and international markets at competitive rates or produce on a scale that rivaled Milwaukee.[4]

Although milling could be an unpredictable business, subject to weather and market fluctuations, Milwaukee’s flour industry grew in importance throughout the late nineteenth century. Annual output in 1854 stood at just 130,000 barrels, but by 1868 that number had risen to 625,000 barrels. A more efficient refining process introduced in the early 1870s, called “high milling,” led to a boom in Milwaukee production. Well-suited to the varieties of spring wheat grown in the Upper Midwest, high milling, coupled with the regional railroad network, gave Minneapolis and Milwaukee advantages over rivals such as St. Louis.[5] By 1892 Milwaukee millers were putting out 2,117,009 barrels of flour per year, more than a fifty percent increase from 1889. Despite these gains, Milwaukee could never truly compete with the Twin Cities, especially as wheat farming moved farther west. Between 1910 and 1919, the centrality of milling in Milwaukee’s economy waned, with production declining from 1,318,565 barrels to 584,883 barrels per year. By 1919, the city was not even producing enough flour for local consumption, and within a year’s time, flour milling was no longer listed as one of Milwaukee’s top ten industries.[6]

Footnotes [+]

- ^ Bayrd Still, Milwaukee: History of a City (Madison, WI: The State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1948), 63-64.

- ^ Frederick Merk, Economic History of Wisconsin during the Civil War Decade, Wisconsin Historical Studies, vol. 1 (Madison, WI: The State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1916), 131-132; L. R. Hurd, “Milwaukee’s Flouring Industries,” in Milwaukee’s Great Industries: A Compilation of Facts Concerning Milwaukee’s Commercial and Manufacturing Enterprises, Its Trade and Commerce, and the Advantages It Offers to Manufacturers Seeking Desirable Locations for New or Established Industries, ed. W. J. Anderson and Julius Bleyer (Milwaukee: Association for the Advancement of Milwaukee, 1892), 149.

- ^ John Gurda, The Making of Milwaukee (Milwaukee: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 1999), 118, 125; Hurd, “Milwaukee’s Flouring Industries,” 151.

- ^ Charles N. Glaab and Lawrence H. Larsen, “Neenah-Menasha in the 1870s: The Development of Flour Milling and Papermaking,” Wisconsin Magazine of History 52, no. 1 (Autumn 1968): 22-25, accessed May 6, 2013.

- ^ Gurda, Making of Milwaukee, 118; Still, Milwaukee, 189; Robert C. Nesbit, The History of Wisconsin, Volume III: Urbanization & Industrialization, 1873-1893 (Madison, WI: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1985), 153-154.

- ^ Still, Milwaukee, 189, 328-329, 495.

For Further Reading

Gurda, John. The Making of Milwaukee. Milwaukee: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 1999.

Hurd, L. R. “Milwaukee’s Flouring Industries.” In Milwaukee’s Great Industries: A Compilation of Facts Concerning Milwaukee’s Commercial and Manufacturing Enterprises, Its Trade and Commerce, and the Advantages It Offers to Manufacturers Seeking Desirable Locations for New or Established Industries, edited by W. J. Anderson and Julius Bleyer, 149-151. Milwaukee: Association for the Advancement of Milwaukee, 1892.

Merk, Frederick. Economic History of Wisconsin during the Civil War Decade. Wisconsin Historical Studies, vol. 1. Madison, WI: The State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1916.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.