Cities supply water for domestic, industrial, and agricultural uses in response to concerns about quality and quantity. Milwaukee first implemented water supply for both domestic and industrial reasons; since then, quality and quantity demands have alternately dominated changes in the water system’s infrastructure.

Water in Milwaukee was available from a private vendor as early as 1840. An 1845 Milwaukie Sentinel (sic) editorial called for a municipally-owned works, along with, public wharves and docks, street improvements, sewers, and the cleaning of small water courses.[1] Agitation on a larger scale began in the 1850s, as city boosters were sure that they were necessary in order to compete with Chicago. Beginning in 1852, a series of larger-scale, privately funded waterworks were proposed. Although the city approved them, vendors failed to begin construction. The intervention of the financial panic of 1857 and the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861 prevented any of these schemes from coming to fruition.

In 1866, the Milwaukee Sentinel noted that it was necessary to walk more than half a mile from the business district to find a pump to supply water that was “pure and wholesome to the taste and smell.”[2] High rates of diarrheal diseases were endemic in Milwaukee. While the link between water supply and disease had not yet been clearly demonstrated, many health practitioners recognized the general relationship between pure water and health.[3] High levels of filth, particularly human and animal wastes, were allowed to remain on the streets, where they were eventually washed into the water table. Most houses had unlined privies, further contributing to the pollution of the supply. Many Milwaukeeans obtained water from a neighborhood pump, even when it was located in the midst of domestic and industrial wastes.[4]

Other pressing reasons for implementing a water supply included fire protection, washing and cleaning streets, metal finishing and other industrial uses,[5] and the aesthetic use of water for fountains in parks. City ordinances requiring house and business owners to maintain rainwater cisterns on the roofs of buildings to aid firefighting were largely unsuccessful. The cisterns rusted and broke, or residents used the water for drinking and bathing purposes in hot weather or periods of drought.[6] For all these reasons, Milwaukee’s boosters, businessmen, and the city hall hierarchy deplored the lack of a city-wide water supply and encouraged the adoption of some system that would improve the city’s image among potential immigrants.

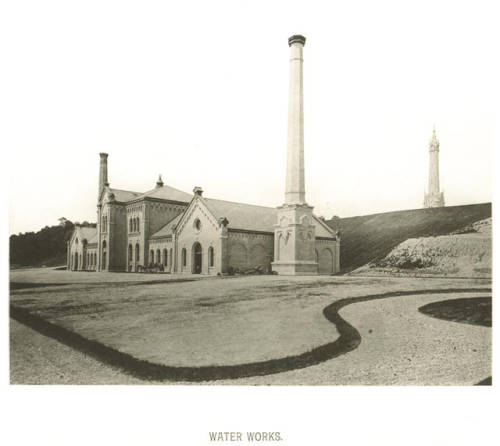

The Common Council in 1868 petitioned the Wisconsin legislature for permission to raise taxes to provide $5,000 for a survey and estimate of possible solutions to their water problems.[7] A pump station at North Avenue, a 700-foot intake into Lake Michigan, a high-service pumping station, a reservoir, and a 135-foot tall standpipe were recommended. All of these required high construction and operation costs. Wards on the east side and downtown could be assured of a plentiful supply, being downhill from the reservoir; the west side required additional booster pumps to ensure sufficient pressure to lift the water to its greater heights.[8] The capacity of the system was to be sixteen million gallons per day (MGD), an amount that would be insufficient by 1888.

To ensure an unbiased decision, the city established a Board of Water Commissioners consisting of private citizens. The commissioners could draft plans, award contracts, condemn property, and authorize expenditures, but the Common Council had the power to amend any of these actions, subject to the approval of the Board. The works were to be funded by the sale of water bonds, taxes levied for construction, water rates, and any other revenues that might derive from the system.[9]

In 1871, the Board hired an engineer, decided how to finance construction and operation, set water rates, issued bonds, and determined a site for the pumping station, intake, and reservoir. In 1872 they reviewed bids and in 1873 surveyed all the city streets to determine the order in which water mains would be laid. Construction proceeded slowly, but water began to flow to the downtown business district and east side wards in 1875. The Board disbanded and turned operations of the water system over to the City.[10] As with most other Midwestern cities, a business model was used; rates were set at a higher level than necessary to cover expenses, and revenue was distributed to the City’s General Fund to allay cost overruns.[11] This model often perpetuated inequality in city services; uninhabited lands and suburbs received priority in distribution, as they had the potential for development and revenue greater than receipts gained from watering poor neighborhoods already within the city. Initially Milwaukee supplied water to the County facilities in Wauwatosa, which allowed wholesale distribution to Wauwatosa and other villages and cities, to the benefit of the city coffers. Milwaukee charged these extra-mural customers a premium of 25% for water; without the capital expenditure of distribution mains and hydrants, the profits from such sales were 40% greater than for watering new areas within the city.[12]

This higher revenue potential, combined with an almost unanimous Democratic vote in the working class Polish neighborhoods, delayed water supply to the South Side for almost three decades.[13] Not until the election of a Socialist city government in 1910 did the Polish wards receive water.

The Socialist administrations were also responsible for reducing the amount of water wasted in the city. They installed water meters for all customers, oversaw quality by creating the positions of water engineer and water chemist, and authorized the appointment of a Water Superintendent to consolidate the previously dispersed functions of the waterworks.[14] Additionally, they argued for a filtration plant in order to improve water quality.

Beginning in 1892, Milwaukeeans began to question the wisdom of disposing of waste into the same body of water from which they drew potable water.[15] In 1905, the city Health Department informed the Common Council that the drinking water was contaminated. Under the Socialists, solutions to the problems were suggested. Possibilities included extending the intake, relocating the pumping station, or building a filtration plant; the City Engineer suggested the water be treated with a chlorine product. The Socialists on the Council independently hired a consultant who recommended the construction of a filtration plant; however, the City Engineer recommended a longer intake, which lowered cost and increased quantity.[16]

The filtration plant plan had many opponents: the Non-Partisans, who preferred to finance a sewage treatment plant; businesses that opposed the higher water rates generated by construction of a filtration plant, and the Republican-dominated state legislature that wanted to control Milwaukee’s debt.[17]

By 1931 the effects of the Great Depression on Milwaukee’s workers were severe enough that constructing a filtration plant won approval as a way to increase employment. A loan from the federal Reconstruction Finance Corporation underwrote costs. It took nearly four years, and a months-long episode of foul-smelling water resulting from the combination of chlorine and industrial waste to overcome the Non-Partisans’ objections to a filtration plant. Construction began in late 1934; the plant went on-line in 1939, with a capacity of 290 million gallons per day.[18]

After WWII, the major political focus in Milwaukee County was annexation. Milwaukee used access to water supply as a carrot-and-stick to encourage residents in postwar developments to vote for annexation with the city. However, the wholesale distribution of water outside the city that had begun in the late nineteenth century was used against Milwaukee’s attempts to annex. A 28-year court case concluded that Milwaukee’s Water Works were operating as a public utility and therefore had both the right to a monopoly in the proposed service areas and the obligation to provide sufficient supply to meet those areas’ needs.[19] Accordingly, the city constructed a second intake and filtration plant on the South Side that opened in 1962. It allowed for an additional 120 MGD of water but was unfortunately located within the outflow plume for the sewage plant.[20]

In late March of 1993 thousands of Milwaukeeans became ill with what appeared to be an intestinal virus. The city Health Department and the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention identified the cause as cryptosporidium, an oocyte that could survive the chlorination and filtration process upon which Milwaukee had relied for purity for over half a century. During a series of public hearings, blame was assigned to city administrators, the water department, and private businesses. Cryptosporidium, a biologic contaminant most often found in animal feces, can cause severe diarrhea, and even death in humans with a weakened immune system. The city’s solution was to redesign the system to both prevent the passage of the oocytes through the filter bed media and monitor water turbidity (cloudiness) that signaled the need for more aggressive chemical treatment. Additionally, both plants were retrofitted to use ozone as a disinfectant, replacing chlorine.[21] This redesign was a Milwaukee innovation; other systems wishing to update their own purification plants use the Milwaukee plants as a model.

The main water issue for Milwaukee in the twenty-first century was whether to supply inland Waukesha County with water from Lake Michigan. The Great Lakes Compact prohibits diverting water from the Great Lakes basin outside the drainage area. Because most of Waukesha County drains to the Mississippi River, using Milwaukee’s water would require the approval of the two local governments and also from the governors of all the states and provinces abutting the Great Lakes basin. The obvious supplier was the city of Milwaukee. However, the city objected to Waukesha’s proposals for a service area to support suburban growth and tried to tie the negotiations to other metropolitan issues, including regional transit. In response, Waukesha partnered with the city of Oak Creek agreed to make the provision; in June 2016, the diversion won approval from the necessary governors.[22]

Milwaukee is currently marketing itself as a “water center,” a place of ready supply and water research. The Water Council, a collaboration between business, government, NGOs, and academia (as represented by the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee School of Freshwater Sciences and Marquette University), opened its Global Water Center in 2013.[23] The Water Council links research, entrepreneurs, and government agencies to find solutions to local, national, and global water issues.

Footnotes [+]

- ^ Milwaukie Daily Sentinel, August 22, 1845.

- ^ Milwaukee Sentinel, January 6, 1866.

- ^ Judith W. Leavitt, The Healthiest City (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1975), 27.

- ^ Leavitt, The Healthiest City, 24; Charles E. Beveridge, A History of Water Supply in the Milwaukee Area (Milwaukee: Metropolitan Study Commission, 1958), 21.

- ^ Bayrd Still, Milwaukee: The History of a City (Madison, WI: Wisconsin State Historical Society, 1975), 199-201. Manufacturers that had previously relied on river water to fulfill their needs were increasingly wary of the polluted water in all three rivers. Besides, these rivers were often frozen during the winter, making it difficult to keep some operations going.

- ^ Still, Milwaukee, 109-11.

- ^ Beveridge, A History of Water Supply in the Milwaukee Area, 2.

- ^ Milwaukee Sentinel, January 1, 4, 7, 10, and 11, 1869. As water does not naturally flow uphill, artificial means are necessary to provide water in districts above the supply (or in this case, the reservoir), requiring fuel and maintenance on these auxiliary pumps.

- ^ Lawrence M. Larson, A Financial and Administrative History of Milwaukee (Madison, WI: n.p., 1908), 109.

- ^ “Minutes of the Board of Water Commissioners of the City of Milwaukee, 1871-1875,” passim.

- ^ Proceedings of the Common Council’s Aldermanic Committees, April 4, 1875.

- ^ Beveridge, A History of Water Supply in the Milwaukee Area, 36.

- ^ Kate Foss-Mollan, Hard Water: Politics and Water Supply in Milwaukee, 1870-1995 (West Lafayette, IN, Purdue University Press, 2001), 63-71.

- ^ Beveridge, A History of Water Supply in the Milwaukee Area, 6.

- ^ Leavitt, The Healthiest City, 122-3.

- ^ John Alvord, Harrison P. Eddy, and George C. Whipple, Summary of the Report of the Sewerage Commission (1911), 13.

- ^ Milwaukee Water Works Annual Report 1914, p. 9; Annual Report 1915, p. 7.

- ^ Joseph P. Schwada, “Milwaukee’s Water Purification Problem,” Journal of the American Water Works Association (October 1934): 1481.

- ^ PSC Docket #2-U-4719, April 2, 1958.

- ^ Black and Veatch, Consulting Engineers, “Report on Water Works System for Metropolitan Area, Milwaukee, Wisconsin,” (Kansas City, MO: n.p., 1959), 103.

- ^ Foss-Mollan, Hard Water, 209.

- ^ Don Behm, “Great Lakes Governors Approve Waukesha Water Request,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, June 20, 2016, last accessed September 3, 2017.

- ^ “Our History,” The Water Council website, last accessed September 8, 2016, http://thewatercouncil.com/wp-content/uploads/Our_History_Web_7-26-2016.pdf, information now available at https://thewatercouncil.com/wp-content/uploads/Our_History_Web_3-1-17.pdf, last accessed September 7, 2017.

For Further Reading

Foss-Mollan, Kate. Hard Water: Politics and Water Supply in Milwaukee, 1870-1995. West Lafayette, IN, Purdue University Press, 2001.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.