The modern movement toward environmental protection in Milwaukee was rooted in the frontier settlement’s first efforts to control water pollution to protect public health. From this beginning, the dynamic interplay of time, technology, science, commerce, and population growth resulted in a gradual expansion of this narrow focus to the conservation of natural resources, starting with forests and eventually evolving into an all-encompassing campaign to protect Earth’s biosphere, of which Milwaukee was a tiny piece.

Milwaukee scientist Increase Lapham (1811-1875) spoke of the pure air, abundant fresh water, rich soils, and gentle beauty he found upon arriving at the Lake Michigan village in 1836. “Wisconsin is, and will continue to be, one of the most healthy places in the world,” Lapham wrote.[1] Time proved him mostly correct, but like all frontier boom towns, Milwaukee soon faced problems that accompanied nineteenth century Americans wherever they settled. By the late 1840s the city prohibited “garbage or filth” on city streets as a strategy to control infectious diseases.[2]

Pioneer Milwaukee drew its drinking water from springs, wells, and the Milwaukee, Kinnickinnic, and Menomonee Rivers, which join in central Milwaukee before emptying into Lake Michigan. Human waste disposal began with outhouses. Swine, cattle, and fowl ran loose in the streets. Street gutters carried sewage directly into the rivers. Waterborne cholera and typhoid fever were seasonal plagues.[3] In 1874, the city finished the North Point Pumping Station on Lake Michigan at North Avenue. The waterworks brought fresh water from an intake offshore and pumped it west to a reservoir, from which it flowed by gravity through pipes to Milwaukee homes, businesses, and industries. Eventually polluted river discharges reached the intake. Disinfectants were added to the incoming water.[4]

Starting in the 1880s, Milwaukee built combined sanitary and storm sewers under the central city. These diverted diluted sewage from street gutters directly into rivers and the lake. Rivers became so putrid that two flushing tunnels were built to move clear Lake Michigan water into the Milwaukee River north of downtown and before it entered the lake at Milwaukee Harbor. The Milwaukee Sewerage Commission, organized in 1913, supervised the 1920 construction of intercepting sewers that directed the combined sewage into a centralized sewage treatment plant on Jones Island in Milwaukee Harbor. The plant employed “activated sludge,” a European technology in which microorganisms feed on sewage, breaking it down into carbon dioxide, water and nitrogen-rich inorganic compounds, or sludge. The sludge was dried, bagged and sold as Milorganite (Milwaukee Organic Nitrogen), a trademarked lawn and garden fertilizer. The clarified water was discharged into the lake. South Shore, a second sewage treatment plant, opened on Lake Michigan at Fifth Avenue and East Puetz Road in 1968.[5]

The combined storm and sanitary sewers continued to pollute the lake during rainstorms, when overflow diluted sewage was diverted to the lake to avoid flooding the sewage treatment plants and basements. In response to lawsuits filed by both the states of Illinois and Wisconsin in the 1970s, a newly organized Metropolitan Milwaukee Sewerage District started construction in 1985 of more than 26 miles of tunnels up to 32 feet in diameter in limestone bedrock 275 to 325 feet beneath the city. In times of rain, sewage overflow is diverted into the tunnels to be pumped up later for treatment. The tunnels, completed in 2010, capture and treat more than 98 percent of the overflow.[6]

Because private wells became contaminated or depleted and because untreated lake water occasionally was tainted with sewage, construction began in 1933 on the Linnwood Water Treatment Plant on the lake east of Lake Park, which filtered and chlorinated lake water. In 1962, a second waterworks was built on Howard Avenue. In 1993, cryptosporidium, a parasite, infiltrated the city’s water supply, afflicting 400,000 people with diarrhea and other symptoms and causing 69 deaths of persons with compromised immune systems. In response, another stage of treatment was installed at the two filtration plants in which ozone is percolated through the water, killing organisms such as cryptosporidium.[7]

Early air pollution took the form of street-level smoke and soot, first from wood stoves and fireplaces in homes and later from coal-burning home furnaces. Home coal furnaces were phased out in Milwaukee after World War II in favor of more convenient, cleaner natural gas, fuel oil or propane. Early factories burned coal and coke and emitted smoke that blackened the distinctive “Cream City” brick buildings, named for the color of the local bricks. At first, smoke pollution was mitigated when industries built taller stacks, sending smoke farther from population centers. In the late twentieth century, coal was burned only in large factories and electrical generating plants. These emitted nitrogen dioxide, a component of smog, and sulfur dioxide, which in the atmosphere became sulfuric acid that precipitated as acid rain, often hundreds of miles from its source.[8]

After World War II, automobiles caused most of Milwaukee’s street-level air pollution.

The highest concentrations routinely were detected near the downtown intersection of Sixth Street and Kilbourn Avenue and later the nearby interchange of Interstate Highways 94 and 43. The internal combustion engine emits volatile organic compounds (VOCs) that in conditions of sunlight and temperature inversions form smog, which is irritating to most people but endangers asthmatics and others who suffer impaired breathing. Smog alerts urging sensitive persons to remain indoors are frequent in summer from Chicago through Sheboygan. Regulating air pollution began with a smoke control officer at Milwaukee County but was moved to the US Environmental Protection Agency and the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources in the 1970s. Milwaukee’s air benefited from federally-imposed automotive emission standards. In the late twentieth century the effects of “greenhouse gases” led to international concern about human-caused climate change, resulting in intense debate between scientists and free market economists and business leaders about the benefits and costs of regulation. Federal limits imposed upon coal-burning power plants were opposed by states, including Wisconsin under Governor Scott Walker.[9]

To Wisconsin pioneers, the abundance of natural resources including water, fertile soils, timber, fuels, and minerals seemed limitless. Lapham recognized the folly of this belief as principal author of a state commission report in 1867, called Report on the Disastrous Effects of the Destruction of Forest Trees Now Going on So Rapidly in the State of Wisconsin.[10] He was the first of a number of Wisconsin citizens who influenced national conservation and environmental policy for the next 150 years, including John Muir (1838-1914), Charles Van Hise (1857-1918), Aldo Leopold (1887-1948), Henry S. Reuss (1912-2002), and Gaylord Nelson (1916-2005).

Lapham’s report explained the importance of forests to climate, soil, recreation, aesthetics, water, fuel, and lumber. His insight that petroleum was a finite source of fuel, destined for depletion, was articulated only eight years after the world’s first successful oil well was drilled in Pennsylvania. His thinking about forests foreshadowed that of Gifford Pinchot (1865-1946), who organized the May 1908 Conference of the Governors, hosted by President Theodore Roosevelt at the White House, an event cited by many as the beginning of the national Conservation Movement.[11]

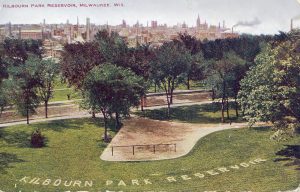

Although the devastation of pine forests from Maine through Minnesota in the last half of the nineteenth century was its impetus, the movement quickly expanded to include minerals, fossil fuels, water, land, soil, fish, wildlife, and songbirds. As a result of the 1908 conference, many states organized conservation departments. The Wisconsin Conservation Commission, predecessor of today’s Department of Natural Resources (DNR), was formed in 1927.[12] The writings of John Muir and others spread awareness that development in the American west threatened wilderness in general and specific natural wonders such as Yosemite and the Grand Canyon. The National Park System originated at Yellowstone in 1872 but grew rapidly, especially after the 1908 conference. Similar efforts arose in states to preserve natural areas, habitat, waterways, and beauty, and to provide recreation. Cities were early to establish public parks. Landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted (1822-1903) was invited to Milwaukee in 1893 to lay out Washington, Riverside, and Lake Parks. Milwaukee County created a Parks Commission in 1907. In the 1920s its longtime director, Charles B. Whitnall (1859-1949), oversaw construction of parkways along urban streams to soften the social impact of a congested, industrializing city; to protect floodplains, and to mitigate runoff pollution.[13]

Whitnall’s concept of linear parks was expanded in a 1967 land use plan prepared for seven counties by the Southeastern Wisconsin Regional Planning Commission (SEWRPC), which identified “primary environmental corridors” and advocated for their permanent preservation. The corridors contain the best remaining natural assets including lakes, streams, forests, glacial moraines, wetlands, native prairie, and wildlife habitats in the seven county southeastern Wisconsin region that includes Milwaukee County. Prominent among the regional corridors was the Kettle Moraine interlobate glacial moraine in Washington and Waukesha Counties west of Milwaukee, a series of northeast-trending ridges and hills composed of glacial drift (clay, sand, gravel, and boulders), carried southward and dropped as two lobes of the Wisconsin glacier thawed 10,000 years ago.[14]

Influenced by two Milwaukee attorneys and outdoorsmen, Haskell Noyes (1886-1948), a leader of the Izaak Walton League of Wisconsin, and Raymond Zillmer (1887-1960), the state of Wisconsin began to acquire the Kettle Moraine in 1936 as two units to be managed as state forests, a northern unit in Sheboygan and Washington Counties and a southern unit in Waukesha and Walworth Counties. Zillmer’s lobbying and the work in Congress by U. S. Representative Henry S. Reuss, from Milwaukee, were instrumental in the creation of the Ice Age National Scenic Trail, a 1000-mile-long footpath that follows the serpentine terminal moraine from the Mississippi River to Janesville and then the interlobate Kettle Moraine to Door County. The Kettle Moraine State Forest is among the most-visited outdoor recreational sites in Wisconsin, used in all seasons by hikers, hunters, skiers, snowmobilers, anglers, picnickers, and birdwatchers, many from Milwaukee, an hour’s drive away.[15]

The Environmental Movement arose in the 1960s from a coincidence of events including the coming of age of the Baby Boomers, the war in Vietnam, an unprecedented prosperity marked by automobile usage and urban sprawl, and the Cold War dominated by an international nuclear arms race. The use of atomic bombs in World War II and the photograph of the Earth from space taken by the Apollo 8 space mission dramatically communicated the realization that Earth’s capacity to support life was limited and vulnerable to human activity. This was reinforced by a growing body of environmental literature that included Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (1962), an indictment of the pesticide DDT for its effects on birds; Paul Ehrlich’s The Population Bomb (1968), a call to slow exponential human population growth; and Barry Commoner’s The Closing Circle (1971), a popular treatise on ecology. In A Sand County Almanac (1948), Wisconsin’s Aldo Leopold argued for “a land ethic” of protection. Reissued in 1968, it was translated into twelve languages and has sold millions of copies. Wisconsin’s US Senator Gaylord Nelson recognized the urgent nature of surging environmentalism on the nation’s campuses. Some radical environmentalists were adopting the tactics of the anti-Vietnam War protesters, who were especially violent at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Nelson sought to channel the student movement in a positive way in what became “Earth Day,” an event that brought young activists together with frontline scientists who were documenting the issues. The first Earth Day was held April 22, 1970. Rallies and river cleanups were held in Milwaukee and across the country. An estimated 22 million participated nationally. On April 21, Nelson delivered an antiwar speech to thousands in Madison, then drove to Milwaukee to appear before 1,700 persons at the Milwaukee Area Technical College with Jane Jacobs, author and urbanologist, where they disagreed about the consequences of human population growth.[16]

Earth Day was followed by quick passage in Washington of a body of environmental law, including an act creating the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act, and the Endangered Species Act. In Milwaukee the cause reinvigorated local chapters of established organizations such as the Audubon Society, the Sierra Club, the Nature Conservancy, and the League of Women Voters and prompted the creation of new ones including Citizens Coalition for Clean Air, Wisconsin’s Environmental Decade (now Clean Wisconsin), and Citizens for a Better Environment. Daily newspapers assigned reporters fulltime to environmental coverage. A popular movement demanded public recycling of household paper, glass, plastic, and metal. Home gardeners practiced composting of kitchen and yard waste for use on vegetable gardens. The Clean Water Act provided federal financial support for improving or replacing obsolete local sewage treatment plants, urgently needed in southeastern Wisconsin, where a 1967 SEWRPC study found that most regional streams had become unfit for partial human body contact such as wading or fishing, to say nothing of swimming.[17]

A decade of sewage treatment improvement restored the upper Milwaukee and other rural rivers to recreational uses such as fishing and canoeing. Preservation of native plant and animal species and eradication of disruptive invasive species emerged as important ecological issues. Dutch Elm Disease, caused by a beetle from Europe, spread to Milwaukee in the 1950s, devastating thousands of mature American elms. Desperate to save the majestic elms, Milwaukee and its suburbs sprayed tons of DDT from trucks and helicopters. Some efforts to control invasive species were futile and others came with unwanted, harmful side effects. Spraying DDT proved lethal to songbirds, interfered with raptor reproduction, and concentrated DDT in the fat cells of fish in Lake Michigan. Lorrie Otto (1920-2010) of suburban Bayside carried carcasses of robins to public meetings in an attempt to stop the spraying of DDT. Failing locally, she and Frederick L. Ott (1921-2008) of Milwaukee, a fellow member of the Citizens Natural Resource Association of Wisconsin, began in 1968 to raise funds and provide logistical support for the national Environmental Defense Fund to demand state hearings on DDT. Wisconsin banned DDT in 1970, a year before a national ban was enacted.[18]

Milwaukee Public Museum scientists identified habitats of endangered or threatened species and engaged in efforts to protect them, including Butler’s Garter Snake, the Karner Blue Butterfly, and the Peregrine Falcon. Annual Earth Days attracted volunteers who cleaned up trash along rivers and highways, dug out garlic mustard, honeysuckle, purple loosestrife, and other invasive species. Zebra and Quagga Mussels in Lake Michigan proved to be intractable problems. In 1969 the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee established its interdisciplinary Center for Great Lakes Studies to study the physical, biological, and institutional aspects of the Great Lakes. Its founding director until 1976 was the eminent zoologist Dr. Clifford H. Mortimer. Shortly later, a government surplus ship was acquired, refitted for research and christened the Neeskay. It was still in service on Lake Michigan in 2016. The Center was incorporated into the new UWM Great Lakes Water Institute in 1998 and became a component of the new UWM graduate School of Freshwater Sciences in 2009, with Dr. J. Val Klump as its senior scientist. The school was the first of its kind the U. S. and reflected the realization that clean, fresh water had become an urgent global resource concern. In 2008 the Milwaukee Water Council was formed by a collaboration of the academic water research community and local water-related industries. In 2015, Marquette University’s Law School announced a Water Law and Policy Initiative. Both events positioned Milwaukee as an internationally important center of freshwater research and protection.[19]

Footnotes [+]

- ^ I. A. Lapham, A Geographical and Topographical Description of Wisconsin (Milwaukee: P. C. Hale, 1844), 92.

- ^ Bayard Still, Milwaukee: The History of a City (Madison, WI: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1948), 239-250.

- ^ “Typhoid Fever in Milwaukee and the Water Supply,” Journal of the American Medical Association 50 (July 16, 1910): 211.

- ^ “History of the Milwaukee Water Works,” City of Milwaukee website, last accessed July 13, 2017.

- ^ “Waste Water Treatment, Sewers,” MMSD website, last accessed July 13, 2017.

- ^ “Waste Water Treatment, Deep Tunnel,” MMSD website, last accessed July 13, 2017.

- ^ Don Behm, “Milwaukee Marks 20 Years since Cryptosporidium Outbreak,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, April 6, 2013, 1.

- ^ Paul G. Hayes, “Coal Furnace Leniency Favored,” The Milwaukee Journal, October 10, 1972, part 2, pp. 1-3.

- ^ Paul G. Hayes, “Air Quality: An Enduring Problem,” Master Planners: Fifty Years of Regional Planning in Southeastern Wisconsin: 1960-2010 (Milwaukee, WI: Marquette University Press, 2010), 130-135.

- ^ I.A. Lapham, J.G. Knapp, H. Crocker, “Report on the Disastrous Effects of the Disastrous Effects of the Destruction of Forest Trees Now Going on So Rapidly in the State of Wisconsin” (1867; facsimile edition published by Madison WI: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1967).

- ^ W.J. McGee, Conference of the Governors of the United States (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1908), vvi.

- ^ Charles R. Van Hise, The Conservation of Natural Resources in the United States (New York: The MacMillan Co., 1910), 114.

- ^ “History of the Parks,” Milwaukee County website, last accessed July 13, 2017.

- ^ Southeastern Wisconsin Regional Planning Commission, “Fifty-fourth Annual Report” (Waukesha, WI: Southeastern Wisconsin Regional Planning Commission, 2015), 9.

- ^ Sarah Mittlefehldt, “Discovering Nature in the Neighborhood: Raymond Zillmer and the Origins of the Ice Age Trail,” in Along Wisconsin’s Ice Age Trail, eds. Eric Sherman and Andrew Hanson III (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 2008), 55-71.

- ^ Bill Christofferson, The Man from Clear Lake: Earth Day Founder Senator Gaylord Nelson (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 2004), 302-312.

- ^ Roy W. Ryling, Water Quality and Stream Flow in Southeastern Wisconsin (Waukesha, WI: Southeastern Wisconsin Regional Planning Commission, 1967).

- ^ Paul G. Hayes, “The Blooming of Lorrie Otto,” Wisconsin: The Milwaukee Journal Magazine (June 28, 1992), 14-16.

- ^ J. Val. Klump, email to author, March 6, 2016, in possession of author.

For Further Reading

Christofferson, Bill. The Man from Clear Lake, Earth Day Founder Senator Gaylord Nelson. Madison, WI: The University of Wisconsin Press, 2004.

Fox, Stephen. The American Conservation Movement, John Muir and His Legacy. Madison, WI: The University of Wisconsin Press, 1981.

Hayes, Paul G. Master Planners, Fifty Years of Regional Planning in Southeastern Wisconsin: 1960-2010. Milwaukee: Marquette University Press, 2010.

Lapham, I. A., J. G. Knapp, and H. Crocker, Report of the Disastrous Effects of the Destruction of Forest Trees Now Going on So Rapidly in the State of Wisconsin. Madison, WI: Atwood and Rublee, State Printers, 1867.

Leopold, Aldo. A Sand County Almanac. New York: Oxford University Press, 1949.

McGee, W. J. Proceedings of a Conference of Governors in the White House, May 13-15, 1908. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1909.

Still, Bayrd. Milwaukee, The History of a City. Madison, WI: The State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1948.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.