An eight-hour day movement flourished for several decades after the Civil War and united thousands of Milwaukee and other American workers who otherwise differed by skill, occupation, race, gender, and ethnicity. Often working ten or twelve hours a day, workers said they needed more time for rest and to be with their families, and insisted they should receive ten hours pay for eight hours of work. Many Milwaukee workers joined nationwide strikes for an eight-hour day in 1886 and supported eight-hour efforts afterwards. But few achieved eight-hour days, and no sweeping wage and hour laws appeared until the 1930s.

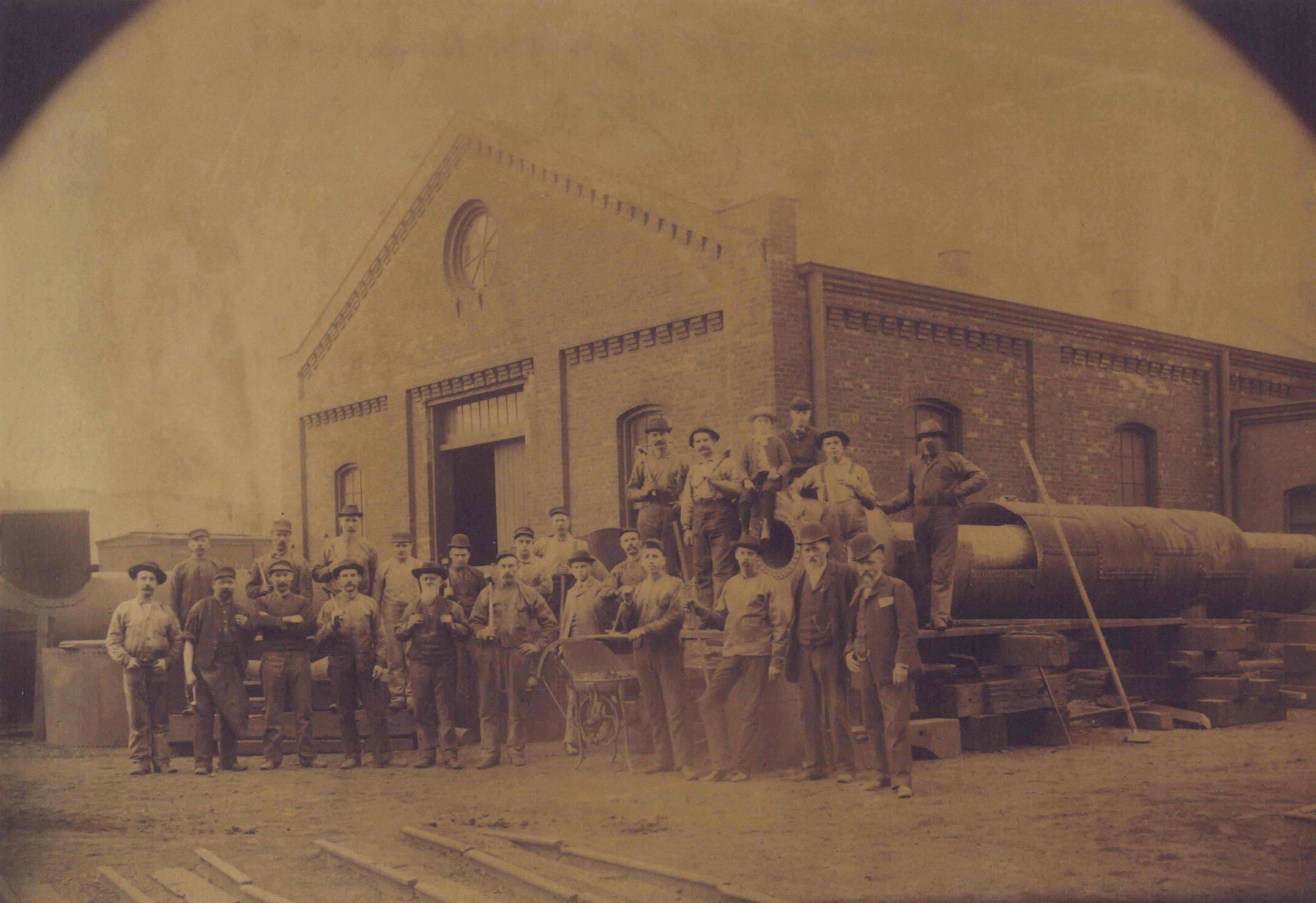

Milwaukee workers formed an Eight-Hour League in 1865.[1] The League dissolved in the 1870s depression. But the national movement revived in 1884 when the Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions (FOOTLU), which became the American Federation of Labor (AFL) in 1886, called on its affiliated unions of skilled workers to seek an eight-hour day by May 1, 1886, and implied they should strike if employers resisted.[2] Terence V. Powderly, leader of the popular and more inclusive Knights of Labor, told local Knights assemblies not to join the eight-hour movement, but Robert Schilling, a Milwaukee Knights leader, and most of the twelve thousand Knights members in the city, disregarded his order, including many Polish laborers who worked at the North Chicago Rolling Mills in Bay View. Schilling even collaborated in a revived Eight-Hour League with socialist Paul Grottkau, editor of the Arbeiter-Zeitung and head of the new Central Labor Union, which rivaled the Knights and had ties to FOOTLU.[3]

By late April, city government employees and workers at some twenty private firms had won an eight-hour day.[4] Other employers claimed that shorter work days would increase their costs and make competition more difficult.[5] By Saturday, May 1, an estimated ten thousand workers were on strike. Worried about possible violence, Governor Jeremiah Rusk readied state troops for duty in Milwaukee. On Monday, roving bands of workers swarmed throughout the city urging workers to join the strike. On Tuesday, Polish members of the Knights marched from St. Stanislaus Church to the nearby rolling mills where state troops turned them back. When some one thousand workers marched again to the rolling mills the next morning, acting on Rusk’s orders Major George R. Traeumer ordered his troops to fire on the crowd. Seven died, including a boy and a man tending his garden.[6]

The eight-hour movement unraveled quickly but sparked new political activity. Schilling launched the People’s Party of Wisconsin, whose candidates in the fall elections won many Milwaukee city and county government positions and state assembly seats. Henry Smith, a millwright, was elected to Congress.[7]

Local unions endorsed the AFL’s new target date for an eight-hour day of May 1, 1890, but the depression of the 1890s stymied the eight-hour movement.[8] Most Milwaukee area workers had no gains in hours and wages until the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 established minimum wages and a forty-four hour work week for workers covered by the law.[9]

Footnotes [+]

- ^ For history of the national eight-hour movement and eight-hour laws in some states, see Philip S. Foner, History of the Labor Movement in the United States. Vol. II, From the Founding of the American Federation of Labor to the Emergence of American Imperialism (New York: International Publishers, 1975), 98; Joseph G. Rayback, A History of American Labor (New York: Macmillan,1959), 116-118; David Roediger, “Ira Steward and the Anti-Slavery Origins of the American Eight-Hour Theory,” Labor History 27 (Summer 1986): 410-426; Hyman Kuritz, “Ira Steward and the Eight Hour Day,” Science & Society 20 (Spring 1956): 118-134; Stanley Nadel, “Those Who Would Be Free: The Eight-Hour Strikes of 1872,” Labor’s Heritage 2 (June 1990): 70-77; Sidney Fine, “The Eight-Hour Movement in the United States, 1888-1891,” Mississippi Valley Historical Review 40 (December 1953): 441-462; and Marion Cotter Cahill, Shorter Hours: A Study of the Movement since the Civil War (New York: Columbia University Press, 1932), 63-91, 262, 267. On Wisconsin’s background and the state’s weak 1867 law, which covered only women and children in manufacturing and provided other exemptions, see Frederick Merk, Economic History of Wisconsin during the Civil War Decade (Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1916), 175, n.2, 179, n. 3, and 181; Robert W. Ozanne, The Labor Movement in Wisconsin: A History (Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1984), 6-7.

- ^ Foner, History of the Labor Movement, 99; Philip Taft, The A.F.L. in the Time of Gompers (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1957), 14-16; Fine, “The Eight-Hour Movement in the United States,” 441-442.

- ^ Thomas W. Gavett, Development of the Labor Movement in Milwaukee (Madison and Milwaukee: University of Wisconsin Press, 1965), 41-58; Foner, History of the Labor Movement, 99-101; Leon Fink, Workingmen’s Democracy: The Knights of Labor and American Politics (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1983), 184-189; Rayback, A History of American Labor, 164-165; Craig Phelan, Grand Master Workman: Terrence Powderly and the Knights of Labor (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2000), 187-189.

- ^ Gavett, Development of the Labor Movement in Milwaukee, 58; Fink, Workingman’s Democracy, 189-192.

- ^ Editorial, “Suggestions for Working Men,” Milwaukee Sentinel, May 2, 1886; and articles by various local employers in the section, “As Seen by Them,” Milwaukee Sentinel, May 2, 1886.

- ^ Gavett, Development of the Labor Movement in Milwaukee, 59-70; Fink, Workingmen’s Democracy, 192-195; John Gurda, The Making of Milwaukee (Milwaukee: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 1999), 150-156; Ozanne, The Labor Movement in Wisconsin, 6-13. See also coverage in the Milwaukee Sentinel and Milwaukee Journal, April 30-May 6, 1886. Nationally, an estimated 185,000 of the 350,000 workers struck for eight hours in May 1886 achieved their goal, if only temporarily. Foner, History of the Labor Movement, 103-104; Fine, “The Eight-Hour Movement in the United States,” 442.

- ^ Gavett, Development of the Labor Movement in Milwaukee, 69; Gurda, The Making of Milwaukee, 159-160.

- ^ For endorsements and coverage of eight-hour activities but also evidence of eight-hour apathy, see Milwaukee Journal, February 23, May 2, and July 5, 1889; Milwaukee Sentinel, February 23 and September 3, 1889, and May 3, 5, and 10, 1890. See also Ozanne, The Labor Movement in Wisconsin, 26-27, 31-33, and chapter 11 (on Wisconsin paper workers’ eight-hour crusade after 1904); and Fine, “The Eight-Hour Movement in the United States,” 442-462.

- ^ See George E. Paulson, A Living Wage for the Forgotten Man: The Quest for Fair Labor Standards, 1933-1941 (Selinsgrove, PA: Susquehanna University Press, 1996), and Jonathan Grossman, “Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938: Maximum Struggle for a Minimum Wage,” Monthly Labor Review 101 (June 1978), 22-30.

For Further Reading

Fink, Leon. Workingmen’s Democracy: The Knights of Labor and American Politics. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1983.

Gavett, Thomas W. Development of the Labor Movement in Milwaukee. Madison and Milwaukee: University of Wisconsin Press, 1965.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.