Beer gardens and beer halls were key early institutions in the vibrant beer culture that accompanied the development of Milwaukee’s iconic brewing industry. Milwaukeeans and visitors from various ethnic and class backgrounds frequented these establishments located throughout the city to drink beer, listen to music, play games, socialize with friends, neighbors, and family, and partake in the city’s famed gemütlichkeit. Beer gardens and halls were also significant retail outlets for the city’s major breweries, who developed these institutions into extravagant commercial entertainment spaces to help market their brands.

Beer gardens and halls were important cultural institutions in the German kingdoms. Local breweries developed these spaces in or near their facilities, where many Germans socialized, celebrated traditions and holidays, shared political ideas, and enjoyed beer and food. As they migrated to Milwaukee, Germans established these familiar spaces to fulfill similar cultural roles in their new communities.

Beer Gardens

Milwaukee was home to at least eleven dedicated beer gardens established between 1840 and 1880. Often bearing the names of their German immigrant proprietors, Milwaukee’s early beer gardens were neighborhood-supported institutions, located in or around large German communities. Opened in 1844, Ludwig’s Garden was located at the foot of the present day Pleasant Street bridge, near early German neighborhoods on Milwaukee’s East Side.[1] Lachner’s Garden, another garden developed in the mid 1840s, was located at the edge of large German communities on Milwaukee’s west side—the present site of Trinity Lutheran Church.[2] As one Milwaukee historian recounts, these gardens were important ethnic institutions “where the German citizenry danced at night, listened to open air concerts, and bought cakes, coffee, and beer.”[3]

Prior to the development of Milwaukee’s municipal park system in the late-nineteenth century, beer gardens fulfilled a growing need for open, public green areas as the city rapidly industrialized and grew denser. Proprietors augmented the city’s natural landscape with ornamental plantings, arbors, nurseries, terraces, animal menageries, and other cultivated elements common to German beer gardens.[4] Beer gardens were also important places for Milwaukeeans to play in warmer weather, with features like shooting galleries, indoor and outdoor bowling alleys, and large open spaces for playing a variety of team sports and field games.[5] Some gardens, like Bielefeld Garden on Ogden Avenue between Astor and Franklin streets, featured an ice skating rink and fire pit for cold weather socializing.[6]

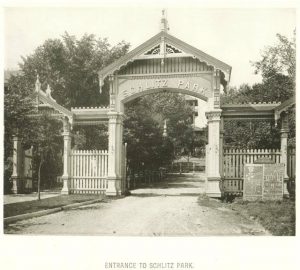

As the expanding city absorbed and redeveloped these early spots, beer gardens followed upwardly mobile Germans to new, larger spaces on the city’s periphery—especially on the north and west sides. By the late 1870s, Milwaukee’s brewing giants recognized the potential of these spaces to improve their brands. In 1879, the Schlitz Brewing Company purchased Quentin’s Park at Eighth and Walnut Streets on the North Side and redeveloped it into what the Milwaukee Sentinel described as a “park whose richness embodies all the hand of art can do in enhancing the beauty of nature.”[7] The renamed Schlitz Park featured refreshment pavilions, bowling alleys, rustic fountains, an open tower that overlooked the city, and a large concert hall that hosted band, choir, and opera performances, as well as balls and dances.[8] The Pabst, Blatz, and Miller brewing companies developed similar lavish pleasure spots in and around the city, including the Pabst Whitefish Bay Resort on the northern lakeshore, Blatz Pleasant Valley Park along the western bank of the Milwaukee River, and Miller’s Garden on the nearby bluffs overlooking the Menomonee River, among others. By the turn of the twentieth century the breweries also installed popular rides and games to accommodate growing demands for the new forms of mass amusement found at Chicago’s 1893 World’s Columbian Exhibition and New York’s Coney Island. In 1885, the Falk Brewing Company installed the city’s first roller coaster in its National Park on the city’s South Side.[9] On the North Side, at the corner of present-day Martin Luther King, Jr. Drive and Burleigh Street, Pabst Park installed roller coasters, a “Katzenjammer castle” funhouse, a scenic miniature railway, an “underground” river boat ride, and various popular midway games in the 1890s.[10]

As the city grew more diverse, beer gardens became popular weekend and holiday picnic sites for Milwaukee families of various backgrounds. They also became key venues for civic, labor, and other community organizations, which regularly organized fundraisers, holiday celebrations, and social gatherings in the city’s major gardens. However, the popularity of the city’s beer gardens gradually faded in the early twentieth century as new amusement parks and an expanding county park system better accommodated changing leisure practices of Milwaukee residents and organizations. National Prohibition put the final nail in the coffin of these once-grand institutions. Pabst Park, the city’s last remaining major beer garden, closed in 1920.[11]

Beer Halls

Whereas the city’s brewers gradually entered the beer garden business in the late nineteenth century, beer halls emerged as significant retail outlets for Milwaukee brewers as they built and expanded their enterprises from the industry’s outset. Jacob Best (founder of Pabst), August Krug (founder of Schlitz), and Frederick Miller, for instance, opened beer halls connected to their pioneer breweries in the 1840s and 1850s, in which they served food alongside their beer.[12] This tradition continued throughout the industry’s development, as the city’s major brewers operated beer halls alongside their breweries as retail outlets and visitor centers into the late twentieth century.

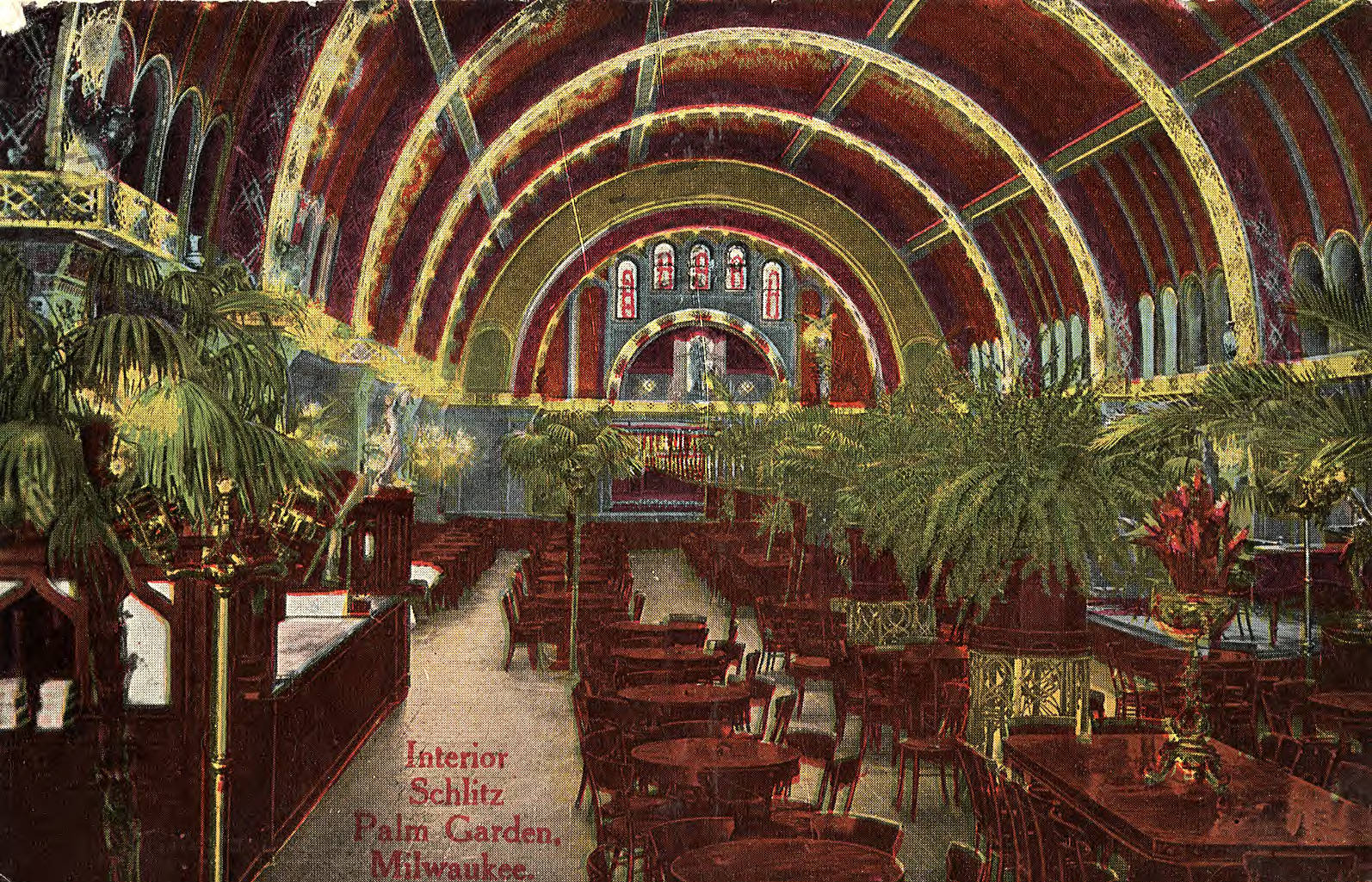

While brewers sought more spacious locations on the city’s periphery for extravagant new beer gardens, they turned to more high-traffic spots downtown for grand new beer halls. In 1851, Charles and Lorenz Best opened a beer hall in the Market Square area, near the present corner of Water and Mason streets, as a downtown outlet for their Plank Road Brewery, later operated by their successor, the Miller Brewery.[13] Their father, Jacob Best, opened a competing beer hall nearby for his Best Brewery shortly thereafter.[14] Brewers invested heavily in the opulence of these spaces through the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries to improve their brands and draw in larger crowds. Among the most famous of Milwaukee’s downtown beer halls was the Schlitz Palm Garden (1896), which featured a large, ornamental vaulted ceiling, and numerous potted palm trees.

Like beer gardens, beer halls hosted an array of band, choir, and opera performances, as well as balls, dances, and other folk celebrations, held year-round.[15] The Schlitz Palm Garden was a popular spot for leisure seekers and family groups to “listen to Arthur Pryor’s or Bohumir Kryl’s bands” in their leisure time.[16] According to one Milwaukee historian, “After-theater audiences from the German theater gathered at the Forst Keller, remodeled from church to rathskeller, to hear Viennese airs played by a string orchestra and listen to the songs of visiting German opera stars.”[17] Milwaukee’s grand downtown beer halls closed in the wake of national Prohibition, and the tradition failed to reemerge with the same vigor after its repeal in 1933.

Recent Revival

Milwaukee’s beer garden and beer hall traditions have recently enjoyed a renaissance in the resurgence of craft brewing, the gradual relaxing of post-Prohibition regulations on brewery relationships with beer vendors, and civic redevelopment efforts of the late twentieth and early twenty-first century. Much like their pioneer predecessors, several of the city’s new craft breweries have established beer halls alongside their brewing operations as retail outlets for their products and venues to promote their brands. Perhaps most notably, Lakefront Brewery’s Beer Hall on North Commerce Street serves as both a visitor center for the brewery and popular spot for many Milwaukeeans to enjoy a traditional Friday night fish fry while listening to polka music. Since 2013, the Milwaukee County Parks Department has also opened popular beer gardens in a number of county parks in partnership with local breweries and restaurants as a means to spruce up deteriorating facilities, boost revenues, and attract more people to the parks system.[18]

Footnotes [+]

- ^ Harry H. Anderson, “Recreation, Entertainment, and Open Space: Park Traditions in Milwaukee County,” in Trading Post to Metropolis: Milwaukee County’s First 150 Years, ed. Ralph M. Aderman (Milwaukee: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 1987), 258; Milwaukee Sentinel, February 21, 1932; William George Bruce, History of Milwaukee, City and County, vol. 1 (Milwaukee: S.J. Clarke, 1922), 768.

- ^ Anderson, “Recreation, Entertainment, and Open Space,” 258; “Famous Gardens and Wein Stuben Gave City Its Charm in the Early Days,” Milwaukee Sentinel, February 21, 1932, Wisconsin Historical Society, Wisconsin Local History & Biography Articles, last accessed December 14, 2018.

- ^ Bayrd Still, Milwaukee: The History of a City (Madison, WI: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1948), 79.

- ^ Anderson, “Recreation, Entertainment, and Open Space,” 258.

- ^ Joseph B. Walzer, “Suds and Solidarity: Outdoor Leisure Spaces and Working Class Identities in Milwaukee, 1880-1925” (master’s thesis, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2009), 16-21; Illustrated Historical Atlas of Milwaukee County, Wisconsin (Chicago, IL: H. Belden, 1876), 43, 89.

- ^ Milwaukee Sentinel, May 2, 1884, p. 3; Charles B. Whitnall, “Milwaukee Parks,” Planning and Development, 1899-1920, Charles B. Whitnall Records, Archives, Milwaukee County Historical Society, Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

- ^ Milwaukee Sentinel, June 26, 1887, p. 6; “Famous Gardens and Wein Stuben Gave City its Charm in the Early Days,” Milwaukee Sentinel, February 21, 1932, Wisconsin Historical Society, Wisconsin Local History & Biography Articles.

- ^ Milwaukee Sentinel, June 26, 1887, 6; Performances were regularly advertised in the Sentinel, e.g. Milwaukee Sentinel, July 5, 1885, p. 8.

- ^ John Gurda, “National Park: Where Milwaukee Went for Thrills 100 Years Ago,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, August 9, 2014, last accessed December 14, 2018.

- ^ Milwaukee Sentinel, June 11, 1885, 3; Anderson, “Recreation, Entertainment, and Open Space,” 261.

- ^ Walzer, “Suds and Solidarity,” 135.

- ^ Kathleen Neils Conzen, Immigrant Milwaukee: Accommodation and Community in a Frontier City (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1976), 104-105; Thomas C. Cochran, The Pabst Brewing Company: The History of an American Business (New York, NY: New York University Press, 1948), 31; Jerry Apps, Breweries of Wisconsin (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1992), 102; Susan K. Appel, “Building Milwaukee’s Breweries: Pre-Prohibition Brewery Architecture in the Cream City,” Wisconsin Magazine of History 78, no. 3 (Spring 1995): 168-169; Wilhelm Otto Keller, “From Miltenberg to Milwaukee: Beer Magnates from the Lower Main Area in the United States in the Nineteenth Century,” trans. Michael R. Reilly, accessed December 19, 2018, http://www.slahs.org/history/brewery/schlitz/miltenberg.htm

- ^ Cochran, The Pabst Brewing Company, 31; John Gurda, Miller Time: A History of Miller Brewing Company, 1855-2005 (Milwaukee: Miller Brewing Company, 2005), 23-26.

- ^ Cochran, The Pabst Brewing Company, 28, 31-32.

- ^ Cochran, The Pabst Brewing Company, 41.

- ^ Still, The Pabst Brewing Company, 403.

- ^ Still, The Pabst Brewing Company, 403.

- ^ Steve Schultze, “Milwaukee County to Solicit Bids for Beer Gardens in Some Parks,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, January 11, 2012. The Milwaukee County Parks System offers a schedule of beer gardens each summer. See https://county.milwaukee.gov/EN/Parks/Explore/Beer-Gardens, accessed October 27, 2018.

For Further Reading

Anderson, Harry H. “Recreation, Entertainment, and Open Space: Park Traditions in Milwaukee County.” In Trading Post to Metropolis: Milwaukee County’s First 150 Years, edited by Ralph M. Aderman, 255-323. Milwaukee: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 1987.

Conzen, Kathleen Neils. Immigrant Milwaukee: Accommodation and Community in a Frontier City. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1976.

Walzer, Joseph B. “Suds and Solidarity: Outdoor Leisure Spaces and Working Class Identities in Milwaukee, 1880-1925.” Master’s thesis, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2009.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.