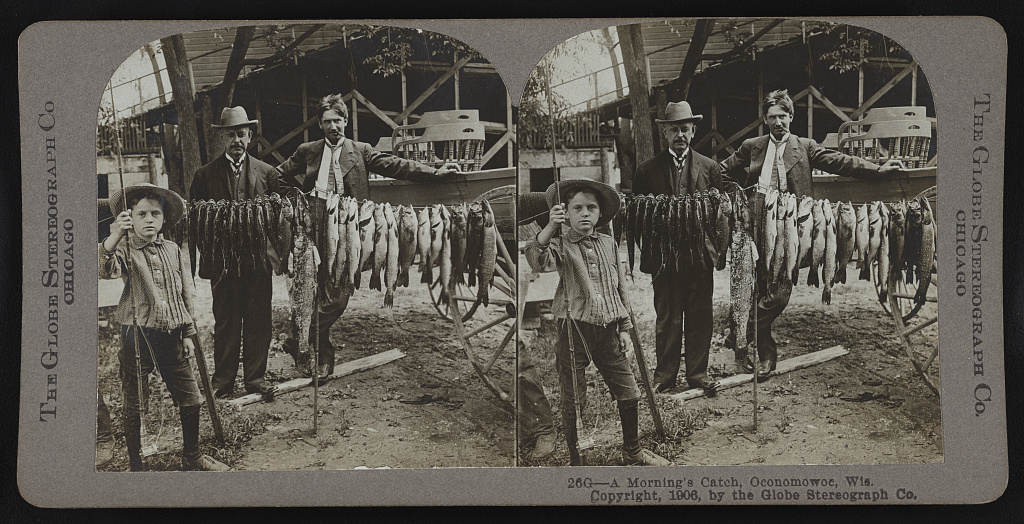

Humans have fished Milwaukee area lakes and rivers for centuries. Natives, fur traders, and early settlers subsisted in part on the fish they caught in these waters. While the commercial fishing industry reduced the need for Milwaukeeans to fish for their survival by the 1860s, many residents continued the practice to maintain a connection to nature, hone new and traditional techniques, and relax.[1] Like other such outdoor pursuits, fishing developed into a popular recreational activity through the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries as leisure time became increasingly separated from work time. Increased industrial wages and vacation benefits also allowed workers to buy gear and take time off for fishing trips.

Recreational (sport) fishing took many forms. Milwaukee men and women fished on area lakes and rivers for pleasure (hobby) or competition; with artificial lures, live bait, flies, or spears; alone or in teams. They fished in boats, or from shore, bridges, and piers, or even while wading in the water. Some anglers braved cold weather to fish through holes they drilled in the ice. Native Americans have spear-fished through the ice of Wisconsin lakes and rivers in winter seasons since well before European settlement. Early pioneers picked up the practice to supplement their winter diet. Ice fishing largely followed the recreational development of warm-weather fishing—gaining popularity with increased leisure time and money. It has particularly boomed since the mid-twentieth century with improvements in heating technology, cold weather clothing, automotive and snowmobile transportation, and other amenities. Ice fishing shanties remain a common sight on the Milwaukee area’s inland lakes in the winter.[2]

Sport anglers also maintained various levels of commitment. Avid anglers spent considerable time and money on mastering fishing techniques, studying fish habits and area aquatic ecosystems, and acquiring the latest gear to catch trophy fish. The less devout used fishing as a means to enjoy nature, socialize, and drink beer on a nice day—perhaps not catching anything at all.[3]

The old wooden piers that extended into Lake Michigan near downtown were popular fishing spots for early Milwaukeeans. “Anglers found rare sport at these landings,” historian John G. Gregory recounts. Noting the large numbers of perch, trout, sturgeon, and catfish fishermen pulled from Lake Michigan, Gregory continues, “Those who came with hook and line and spear rarely missed their share of lake food.”[4] Milwaukee, Port Washington, and other lakeside communities established new fishing piers and fish-cleaning stations as they developed harbor facilities, marinas, and lakeshore parklands through the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Built in the mid-to-late twentieth century, Milwaukee’s McKinley Marina and South Shore Yacht Club also offered sport anglers access to Lake Michigan fisheries by boat, pier, or on the ice, as well as well-equipped fish-cleaning facilities.[5]

Area rivers and connecting waterways were popular fishing spots, as well. One pioneer recalled that Horace Chase and other early Milwaukeeans caught “great numbers” of fish from a brook that flowed from the current intersection of Second and Mineral Streets to a meadow west of Muskego Road.[6] Gregory notes, “There was excellent fishing in the Milwaukee River till [sic] the pollution of the water following the construction of sewers and the introduction of plumbing into the houses of the city [in the 1870s],” after which anglers moved to cleaner waters north of the North Avenue dam.[7]

Urban and agricultural development, pollution, overfishing, and invasive species depleted Milwaukee area fisheries.[8] A growing statewide conservation movement sought to preserve and restore fish populations and their natural habitats. The Milwaukee County Park Commission and state conservationists launched major land acquisition campaigns in the 1920s, preserving areas along the Milwaukee and Menomonee Rivers and portions of the Kettle Moraine—a large band of rolling hills, lakes, and marshes north and west of Milwaukee. New Deal Civilian Conservation Corps and Works Progress Administration workers improved public access to these areas, and state conservation agents increasingly regulated fishing activities to manage fish populations.[9] State, county, and municipal officials also worked to stock local waterways with fish species that would increase recreational fishing traffic. Perhaps most notably, the Michigan Department of Conservation began releasing hatchery-raised salmon into Lake Michigan as a way to boost the sport fishing economy of declining commercial fishing communities in the mid-1960s. Such efforts generated new environmental and regulatory challenges by the 1980s as Lake Michigan gained a reputation as the “world’s greatest fishing hole.”[10]

A growing recreational fishing industry accompanied these conservation efforts in the mid-to-late twentieth century. Rural communities cultivated tourist and entertainment economies as new infrastructure drew more leisure seekers into Milwaukee’s hinterlands. Resorts and bait shops popped up around Pewaukee Lake in Waukesha County, Cedar Lake in Washington County, and other Milwaukee area lakes. North Woods resorts promised visiting anglers “a real sportsman’s paradise, in the uncrowded country filled with myriads of clear, cool lakes and rivers as nature made them.” Both Up North and in the Milwaukee area, local guides offered fishing charters to tourists unfamiliar with the waterways.[11]

The increased popularity of recreational fishing inspired new venues for sharing a passion for fishing through the twentieth century. “Rod and gun” clubs have long been part of Milwaukee’s social history. Once such club, the Minne Ha Ha Fishing Club—presumably named after the character in Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s The Song of Hiawatha—registered as a corporation in Milwaukee in 1904.[12] Many other Milwaukee area clubs have emerged since the boom in Great Lakes sport fishing in the 1960s. These groups offered members a community to share their passion for the sport, exchange knowledge, organize fishing excursions and tournaments, and promote conservation and safety.[13] Anglers also found fishing information through a variety of media outlets. In the 1910s, the Milwaukee Sentinel published the nationally syndicated “Rod and Reel” column featuring fishing tips, fish stories, and answers to reader-submitted questions.[14] Since the 1940s, the Journal Sentinel Sports Show has exhibited the latest in gear, techniques, and excursions for local outdoor enthusiasts, including anglers.[15] Since the 1960s, local and national fishing television programs, like The Fishing Hole, Bill Dance Outdoors, and Due North Outdoors, showed off effective fishing equipment and practices, as well as promising regional locations. In the twenty-first century, the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources and other fishing websites offered area anglers live updates on weather and water conditions, as well as information on how many and what kinds of fish have been recently caught.[16]

Although the Milwaukee area’s commercial fishing industry has long since dwindled, Milwaukeeans remain well connected to the fishing traditions of their forebears—not for survival, but for fun.

Footnotes [+]

- ^ Margaret Beattie Bogue, Fishing the Great Lakes: An Environmental History, 1783-1933 (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 2001), 5-9; John Gurda, The Making of Milwaukee (Milwaukee: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 1999), 6-9, 135; Ruth Kriehn, The Fisherfolk of Jones Island (Milwaukee: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 1988), 1-27; William George Bruce, History of Milwaukee, City and County, vol. 1 (Milwaukee: S.J. Clarke, 1922), p. 63-72, 116.

- ^ David R. M. Beck, “Return to Namä’o Uskíwämît: The Importance of Sturgeon in Menominee Indian History,” Wisconsin Magazine of History 79, no. 1 (Autumn 1995): 43; Kathleen Schmitt Kline, Ronald M. Bruch, and Frederick P. Binkowski, People of the Sturgeon: Wisconsin’s Love Affair with an Ancient Fish (Madison, WI: Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 2009) 65-72, 108-131.

- ^ Fred Whoriskey, “Fishing as Sport,” in Encyclopedia of Animal Rights and Animal Welfare, 2nd ed., ed. Marc Bekoff, vol. 1 (Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood, 2009), 277-280; Richard L. Hummel, “Fishing,” in The American Midwest: An Interpretive Encyclopedia, Richard Sisson, Christian Zacher, and Ander Cayton, eds. (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2007), 922-923; Robert C. Willging, History Afield: Stories from the Golden Age of Wisconsin Sporting Life (Madison, WI: Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 2011).

- ^ John G. Gregory, History of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, vol. 1 (Milwaukee: S.J. Clarke, 1931), 319.

- ^ Harry H. Anderson, “Recreation, Entertainment, and Open Space: Park Traditions in Milwaukee County,” in Trading Post to Metropolis: Milwaukee County’s First 150 Years, ed. Ralph M. Aderman (Milwaukee: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 1987), 311; “Our Origins,” South Shore Yacht Club, accessed July 22, 2019; Paul A. Smith, “Ice off McKinley Marina Yields Rainbow, Brown Trout,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, January 15, 2011, last accessed August 30, 2019; Carl Baehr, “Lincoln Memorial Dr. Was under Water,” Urban Milwaukee, May 20, 2016; “Club History,” South Milwaukee Yacht Club, accessed August 6, 2019; Paul A. Smith, “Program to Provide Fish to the Needy,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, July 20, 2016, last accessed August 30, 2019.

- ^ James S. Buck, Pioneer History of Milwaukee: From the First American Settlement in 1833 to 1841 (Milwaukee: Swain & Tate, 1890), 111

- ^ Gregory, History of Milwaukee, 2: 1058.

- ^ Bogue, Fishing the Great Lakes, 141; Robert C. Nesbit, The History of Wisconsin, vol. 3, Urbanization and Industrialization, 1873-1893 (Madison, WI: The State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1985), 258; Kriehn, The Fisherfolk of Jones Island, 37, 45-46; “Governor Goes Fishing,” Milwaukee Journal, February 10, 1940, sec. 1, p. 1; “Outlook for Revived Lakes Fishing Improved,” Milwaukee Journal, January 12, 1965, sec. 1, p. 1.

- ^ C.L. Harrington, “The Story of the Kettle Moraine State Forest,” Wisconsin Magazine of History 37, no. 3 (Spring 1954): 143-145; Sarah Mittelfehldt, “The Origins of Wisconsin’s Ice Age Trail: Ray Zillmer’s Path to Protect the Past,” Wisconsin Magazine of History 90, no. 3 (Spring 2007): 4; Kriehn, The Fisherfolk of Jones Island, 34-35.

- ^ Dan Egan, The Death and Life of the Great Lakes (New York, NY: W.W. Norton, 2017), 75-107; Kristin M. Szylvian, “Transforming Lake Michigan into the ‘World’s Greatest Fishing Hole’: The Environmental Politics of Michigan’s Great Lakes Sport Fishing, 1965-1985,” Environmental History 9, no. 1 (January 2004): 102-127.

- ^ Aaron Shapiro, The Lure of the North Woods: Cultivating Tourism in the Upper Midwest (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2013), 121-152, quote from p. 145.

- ^ R.H. Odell, Official Directory of Corporations of Milwaukee, Wisconsin (Milwaukee: Odell & Owen, 1904), 142.

- ^ “Wisconsin Fishing Clubs/Associations,” Great Lakes Sport Fishing Council, accessed July 22, 2019; Dave Marcouiller, Patrick Schmalz, and Will Sierzchula, “Tournament Angling in Wisconsin: Estimating Economic Impacts for Host Communities,” Department of Urban and Regional Planning, University of Wisconsin-Madison/Extension (February 2007), last accessed August 30, 2019.

- ^ For an example of this column, see Dixie Carroll, “Rod and Reel,” Milwaukee Sentinel, August 16, 1917, p. 7.

- ^ “History,” Journal Sentinel Sports Show, accessed July 22, 2019.

- ^ “Lake Michigan Outdoor Fishing Report,” Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, July 15, 2019, last accessed August 30, 2019; Pewaukee Lake, Lake Link, accessed July 22, 2019.

For Further Reading

Bogue, Margaret Beattie. Fishing the Great Lakes: An Environmental History, 1783-1933. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 2001.

Egan, Dan. The Death and Life of the Great Lakes. New York, NY: W.W. Norton, 2017.

Kline, Kathleen Schmitt, Ronald M. Bruch, and Frederick P. Binkowski. People of the Sturgeon: Wisconsin’s Love Affair with an Ancient Fish. Madison, WI: Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 2009.

Shapiro, Aaron. The Lure of the North Woods: Cultivating Tourism in the Upper Midwest. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2013.

Szylvian, Kristin M. “Transforming Lake Michigan into the ‘World’s Greatest Fishing Hole’: The Environmental Politics of Michigan’s Great Lakes Sport Fishing, 1965-1985.” Environmental History 9, no. 1 (January 2004): 102-127.

Willging, Robert C. History Afield: Stories from the Golden Age of Wisconsin Sporting Life. Madison, WI: Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 2011.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.