A neighborhood is a small section of a larger municipality that residents understand as a connected territory near their homes. Sometimes neighborhoods have names and generally recognized boundaries; other times their definition is more diffuse.[1] Because modern cities vary so much internally, urban planners and scholars use bounded neighborhoods to understand local differences in population and social indicators to compare places within a municipality.

Milwaukee has many residential neighborhoods. But being a “city of neighborhoods” does not mean that all Milwaukeeans agree on what the neighborhoods within the city are—or even where they are. Nor does it mean that the neighborhoods that are recognized today would have been familiar to Milwaukeeans in the past. Milwaukee’s changing boundaries, which expanded repeatedly for more than a century after its incorporation, exacerbated the problem of identifying neighborhoods. For example, Mayor Frank Zeidler’s (1948-1960) annexation campaign brought 42 square miles of new land into the city. Most of that property was not yet built up, much less subdivided into distinctive neighborhoods.

Early Milwaukeeans recognized three different kinds of geographical categories describing the city’s sections: divisions, sides, and wards. Neighborhoods followed quickly. These terms are still all in use in the twenty-first century. Historian John Gurda, whose research has been instrumental in defining Milwaukee’s contemporary neighborhoods, observes that they are “quicksilver creations, constantly changing residents, borders, and even names.”[2] Milwaukeeans live, play, and work in neighborhoods, but the city lacks a system for identifying and presenting information about them as distinct entities and how they change over time.

The Milwaukee, Menomonee, and Kinnickinnic rivers carved Milwaukee into geographic “divisions” designated by their polar directions. The importance of this spatial alignment was signified in the names of the Milwaukee Public Schools’ North, South, East, and West Division High Schools. These four schools were constructed in each division in the late 1880s, 1890s, and 1906 to serve students who pursued secondary education.[3]

Riverine geography also translated the rivalries among Milwaukee’s earliest prominent landowners—Solomon Juneau, Byron Kilbourn, and George Walker—into the “Sides” that shaped early municipal politics. While Walker’s land claim languished,[4] Juneau and Kilbourn competed ferociously for residents and commerce on opposite banks of the Milwaukee River. As historian Bayrd Still noted, the legal plat for Juneau’s holdings issued in 1835 was called “Milwaukee East Side River,”[5] while Kilbourn’s settlement incorporated in 1837 under the awkward name of “The Town of Milwaukee on the West Side of the River.”[6] At the time, as dramatically evidenced by the 1845 Bridge War, Juneau and Kilbourn seemed to be cultivating adjacent, competing municipalities instead of laying the foundation for a unified city. As Milwaukee coalesced into a three-district village after its 1838 incorporation, Juneau’s, Kilbourn’s, and Walker’s holdings gave their names to the city’s first neighborhoods: Juneautown, Kilbourntown, and Walker’s Point.

The distinctions among these first three neighborhoods were legitimized as they were designated the first three wards, each enjoying great political autonomy.[7] When Milwaukee became a city in 1846, it was further divided into five wards. As Milwaukee’s boundaries expanded through the mid-twentieth century, the number of wards grew as well, reaching a high of twenty-seven in 1934.[8] The boundaries of the wards shifted with each redistricting. The changing boundaries of wards, as well as their designation by numbers, meant that while they were necessarily political units, they did not function as socially cohesive or stable neighborhoods.[9] Nor were wards suitable for presenting data about local change over time. In 1972, legal changes in Wisconsin required the abolition of Milwaukee’s political wards and their transformation into aldermanic districts.[10]

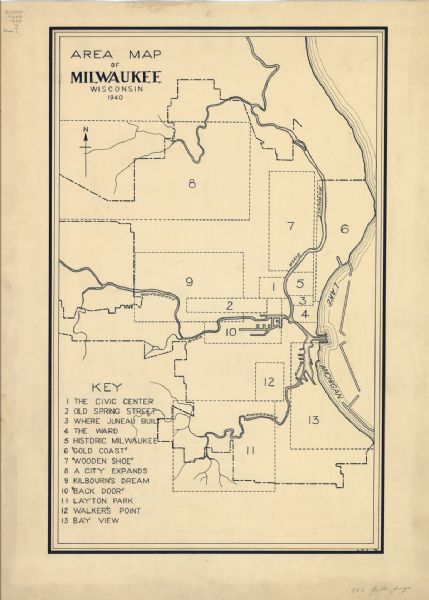

In 1940, the Federal Writers Project produced a map dividing the city into thirteen distinct areas for their Guide to Milwaukee. Modern Milwaukeeans would recognize some of the names assigned to these Milwaukee neighborhoods, such as Layton Park, Walker’s Point, and Bay View. But other, more colorful designations have disappeared from more recent neighborhood names. The “Wooden Shoe” roughly corresponded to contemporary Riverwest, and “Back Door” was the label given to the Menomonee Valley.[11]

After the 1940 census, for the first time the US Census Bureau divided Milwaukee into 153 tracts. This new category made it possible to examine how subareas of the city varied demographically. In 1945, optimistic about the prospects for stable census tracts boundaries, the Citizens’ Bureau of Milwaukee compiled Census Tract Facts: A Handbook of Basic Social Data of Milwaukee County, Wis. To facilitate the work of social service agencies and government, it reported federal census data, city public health statistics, and a list of local amenities for municipalities within Milwaukee County and each of the census tracts.[12]

Social scientists at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee (UWM) attempted to extend this work by codifying Milwaukee’s neighborhoods in the decades after World War II. They followed the model of the stable “community areas” and the Local Community Fact Book series that documented demographic and housing data about Chicago during the twentieth century.[13] The UWM scholars aspired to make similar longitudinal information available for Milwaukee. Their unit of analysis was the neighborhood, which assembled several census tracts together into a larger unit that residents might have recognized.

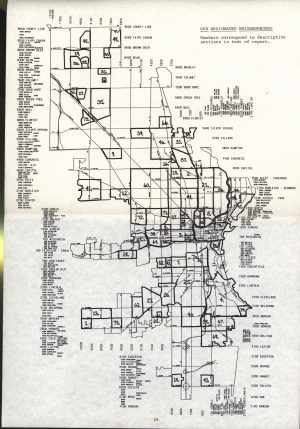

Sociology professor H. Yuan Tien published the first Milwaukee Metropolitan Area Fact Book in 1962, presenting data from the 1940, 1950, and 1960 U.S. censuses as well as the Milwaukee Health Department.[14] Tien drew on a set of thirty-four “economic and community areas” used by the Milwaukee Journal’s Market Research Division and work conducted by the Milwaukee Metropolitan Study Commission in 1958. Tien divided the city into fifty-eight numbered “community statistical areas.” The book also provided data for the other cities, towns, and villages within Milwaukee County, reflecting awareness that cities are best understood in their larger geographical contexts.[15]

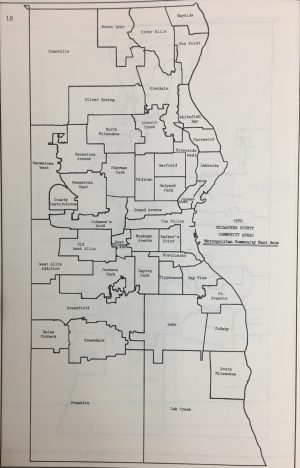

In 1972, UWM followed up with a second volume, using the 1970 federal census and funded by the U.S. government’s Department of Health, Education and Welfare.[16] The new project was formally directed by faculty members J. John Palen and then Robert P. Stuckert under the aegis of UWM’s Milwaukee Urban Observatory. But in practice it was spearheaded by graduate research assistant Frances Beverstock, who also wrote a separate lengthy explanation of the project’s production.[17] In delineating the “community areas” for the 1970 Metropolitan Milwaukee Fact Book, Beverstock and Stuckert redivided Milwaukee into twenty-three named (but not numbered) areas. They also broke Wauwatosa into three subdivisions and West Allis into two. They broadened the project’s scope by providing data for the other municipalities within Milwaukee County as well as several municipalities in Ozaukee, Washington, and Waukesha counties. In the process, they accounted for recent changes to Milwaukee’s boundaries, including the settlement of the controversial annexation of Granville. In order to encourage analysis across time, the new volume retrofitted the new community area boundaries to obsolete census tracts and included data for 1950 and 1960 as well as 1970. UWM gave less support to the effort to repeat the project after the 1980 census. Miriam G. Palay compiled data for 1980 but distribution of her research was limited.[18]

Milwaukee’s Department of City Development (DCD) picked up defining Milwaukee’s neighborhoods where UWM left off. During the 1980s, Milwaukee historian John Gurda and DCD’s Janice Kotowicz collaborated to create a series of posters about the city’s neighborhoods as part of the Discover Milwaukee Program. The front side of the posters illustrated the selected neighborhoods, and the back narrated each area’s history.[19] Gurda elaborated on this system in his 2015 book Milwaukee: City of Neighborhoods, which was published by Historic Milwaukee, Inc. Lavishly illustrated with historical images and new photographs and maps, the book tweaked Gurda’s original list of twenty-nine neighborhoods by changing the names of four, subtracting another four, and adding twelve new ones to the list. Even so, it left large expanses of Milwaukee uncovered. Gurda confined his work to the city as it had been before the annexations of the Zeidler and Henry Maier administrations on the grounds that “the postwar city tends to be largely one piece.”[20]

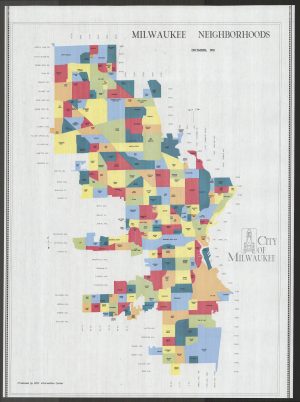

While the poster series was popular with city residents, who framed and displayed the front sides as artwork, DCD also needed systematic data about the city’s subdivisions for planning purposes. In 1989 a student team from the Future Milwaukee organization[21] collaborated with DCD to find out what neighborhood names Milwaukeeans actually used for the places they lived. A survey process that accounted for physical landmarks and resident input resulted in a map that named seventy-five “neighborhood areas” within Milwaukee, although it did not identify a neighborhood for every square inch of the city.[22] In 1992, DCD’s Information Center published a new map identifying 177 distinct Milwaukee neighborhoods and covering the city’s entire area.[23]

The DCD map (republished in 2000) provided the foundation for much subsequent work, although sometimes the number of neighborhoods and their boundaries vary from the city’s official preferences. The Big Stick Company publishes a poster-sized map of Milwaukee neighborhoods for sale as wall art in its series of American city neighborhood maps; it appears to be based on the 2000 DCD map.[24] In the 2010s, Urban Anthropology Inc. used the city’s list as the foundation for their own Milwaukee neighborhoods digital project, including census data, historical narratives, photographs, primary sources, and oral history interviews for each of the 191 neighborhoods on their website.[25] An interactive online map of unclear provenance showed the boundaries for 202 Milwaukee neighborhoods.[26] Real estate dealers, cultural brokers, Wikipedia, and other interested urbanites all work with their own definitions for Milwaukee neighborhoods and neighborhood boundaries.[27]

In the twenty-first century, Milwaukeeans, scholars, and public officials use several different systems to identify the city’s neighborhoods. Across Milwaukee’s history, approaches to mapping residents’ mental maps of the city have proliferated, but no permanent consensus has been established.

Footnotes [+]

- ^ For an overview of the some of the definitions of neighborhood used in American culture, see Benjamin Looker, A Nation of Neighborhoods: Imagining Cities, Communities, and Democracy in Postwar America (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2015), 2-3.

- ^ John Gurda, Milwaukee: City of Neighborhoods (Milwaukee: Historic Milwaukee Incorporated, 2015), xi.

- ^ Bayrd Still, Milwaukee: The History of a City (Madison, WI: The State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1965; originally published 1948), 415.

- ^ Gurda, Making of Milwaukee, 37-38, 49.

- ^ Still, Milwaukee, 19.

- ^ Still, Milwaukee, 34.

- ^ Still, Milwaukee, 36.

- ^ Map, City of Milwaukee Showing Ward Boundaries (Milwaukee: Milwaukee City Engineer’s Department, 1934), last accessed May 27, 2019; 1940 US Census, Wisconsin, p. 1175, last accessed May 27, 2019. In the 21st century, election wards are now subunits of Milwaukee’s 15 aldermanic districts. See Map of City of Milwaukee Aldermanic Districts: 2012, City of Milwaukee website, last accessed August 18, 2017, and City of Milwaukee Redistricting, Final Aldermanic and Voting Wards, June 2012, City of Milwaukee website, last accessed August 18, 2017.

- ^ To see how the city grew and the ward boundaries changed, see Still, Milwaukee, 596-599.

- ^ For an overview of how the wards became aldermanic districts, see Angelina Mosher Salazar, “Race, Representation & Redistricting: Why Milwaukee’s Wards Became Districts,” WUWM, January 11, 2019, last accessed February 12, 2019.

- ^ John D. Buenker, ed., Milwaukee in the 1930s: A Federal Writers Project City Guide (Madison, WI: Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 2016), 13-162.

- ^ Census Tract Facts: A Handbook of Basic Social Data of Milwaukee County, Wis. (Milwaukee: Statistical-Research Dept. of the Milwaukee Community Fund and Council of Social Agencies, 1945).

- ^ Louis Wirth, Local Community Fact Book, 1938 (Chicago, IL: Chicago Recreation Commission, 1938); Louis Wirth, Eleanor Sheldon, Harriet Bernert, and Chicago Community Inventory, Local Community Fact Book of Chicago ([Chicago, IL]: University of Chicago Press, 1949); Philip M. Hauser, Evelyn Mae Kitagawa, Louis Wirth, and Chicago Community Inventory, Local Community Fact Book for Chicago, 1950 ([Chicago, IL]: Chicago Community Inventory, University of Chicago, 1953); Evelyn Mae Kitagawa and Karl E. Taeuber, Local Community Fact Book: Chicago Metropolitan Area, 1960 (Chicago, IL: Chicago Community Inventory, University of Chicago, 1963); Chicago Fact Book Consortium, Local Community Fact Book: Chicago Metropolitan Area: Based on the 1970 and 1980 Censuses (Chicago, IL: Chicago Review Press, 1984); Chicago Fact Book Consortium, Local Community Fact Book: Chicago Metropolitan Area: Based on the 1990 Census (Chicago, IL: University of Illinois at Chicago, 1995).

- ^ H. Yuan Tien, ed., Milwaukee Metropolitan Area Fact Book: 1940, 1950, 1960 (Madison, WI: The University of Wisconsin Press, 1962), 3.

- ^ Tien, Milwaukee Metropolitan Area Fact Book, 4.

- ^ Frances B. Beverstock, Getting It All Together in Milwaukee: From Census Data to Fact Book in Thirteen Steps or More (Milwaukee: University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 1972), 3.

- ^ Frances Beverstock and Robert P. Stuckert, Metropolitan Milwaukee Fact Book: 1970 (Milwaukee: Milwaukee Urban Observatory, 1972); Beverstock, Getting It All Together in Milwaukee (1972) and Frances B. Beverstock, Getting It All Together in Milwaukee: From Census Data to Fact Book in Thirteen Steps or More, 2nd edition (Milwaukee: University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 1973).

- ^ Miriam Palay, “Greater Milwaukee 1970-1980 Census Data, by Race and Spanish Origin” (Milwaukee: Milwaukee Urban Observatory, 1981); Miriam G. Palay and Milwaukee Urban Observatory, “Full Count 1980 Census Information, Greater Milwaukee Area and 1970-1980 Percentages” (Milwaukee: Milwaukee Urban Observatory, 1982); Miriam Palay and University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, Division of Urban Outreach, “Census Facts: Milwaukee Areas and Neighborhoods, 1970-1980 Statistics Compared” (Milwaukee: Division of Urban Outreach, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, University of Wisconsin-Extension, 1984). The 1982 volume, “Full Count 1980 Census Information, Greater Milwaukee Area and 1970-1980 Percentages,” most closely paralleled the previous fact books but lacked narratives about the neighborhoods. A WorldCat search reveals that it is held in six libraries. According to WorldCat, “Census Facts” is held in three libraries.

- ^ Gurda, Milwaukee, xii.

- ^ Gurda, Milwaukee, xiii.

- ^ Future Milwaukee is a leadership program for young professionals now based at Marquette University. About Future Milwaukee, Marquette University website, last accessed July 27, 2017.

- ^ Karen Hendrickson et al., “The Neighborhood Identity Project” (Milwaukee: [Future Milwaukee], 1989).

- ^ The earliest version of this map is available in the City of Milwaukee’s Municipal Research Center. The 2000 version is available online, Milwaukee Neighborhoods map (2000), last accessed July 27, 2017. Another version of this map from around the same time, with slightly different annotations, is available in the American Geographical Society Library in the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Libraries.

- ^ Neighborhoods of Milwaukee collection finding aid, Milwaukee County Historical Society website; Milwaukee, WI, Neighborhoods, Area Vibes website; 2018 Best Neighborhoods to Live in the Milwaukee Area, Niche website; Explore Our Neighborhoods, Visit Milwaukee website; Milwaukee Neighborhood Map, Neighborhood Ties Inc. website, accessed July 27, 2017.

- ^ 191 Milwaukee Neighborhoods website, last accessed July 27, 2017.

- ^ Milwaukee Neighborhoods, Google maps, last accessed July 27, 2017.

- ^ Discover Milwaukee Relocation Guide (2018), p. 36, Discover Milwaukee website; List of Neighborhoods of Milwaukee, Wikipedia, both last accessed February 12, 2019.

For Further Reading

Beverstock, Frances, and Robert P. Stuckert. Metropolitan Milwaukee Fact Book: 1970. Milwaukee: Milwaukee Urban Observatory, 1972.

Buenker, John D., ed. Milwaukee in the 1930s: A Federal Writers Project City Guide. Madison, WI: Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 2016.

Gurda, John. Milwaukee: City of Neighborhoods. Milwaukee: Historic Milwaukee Incorporated, 2015.

Looker, Benjamin. A Nation of Neighborhoods: Imagining Cities, Communities, and Democracy in Postwar America. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2015.

Palay, Miriam G., and Milwaukee Urban Observatory. “Full Count 1980 Census Information, Greater Milwaukee Area and 1970-1980 Percentages.” Milwaukee: Milwaukee Urban Observatory, 1982.

Tien, H. Yuan. Milwaukee Metropolitan Area Fact Book, 1940, 1950, and 1960. Madison, WI: The University of Wisconsin Press, 1962.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.