Milwaukee has hosted many visitors for organizational meetings, major conventions, and personal or business travel throughout its history. The city’s tourism industry grew along with the city, as an array of businesses, organizations, and civic leaders worked both independently and together to attract, accommodate, and ultimately profit from these guests.

Milwaukee’s earliest visitors were often new settlers of the frontier community or pioneers continuing on their way to other destinations in the region. The city’s first guest accommodations emerged in the mid-1830s to meet the needs of these travelers. Jacques Vieau established Milwaukee’s first hotel, the Cottage Inn, on East Water Street in 1835, and a host of other pioneer hostelries soon followed.[1] Seeing the potential of such lodging in the growth of their communities, both Solomon Juneau and Byron Kilbourn offered aspiring hotel entrepreneurs land and other incentives to encourage them to build in their respective settlements.[2]

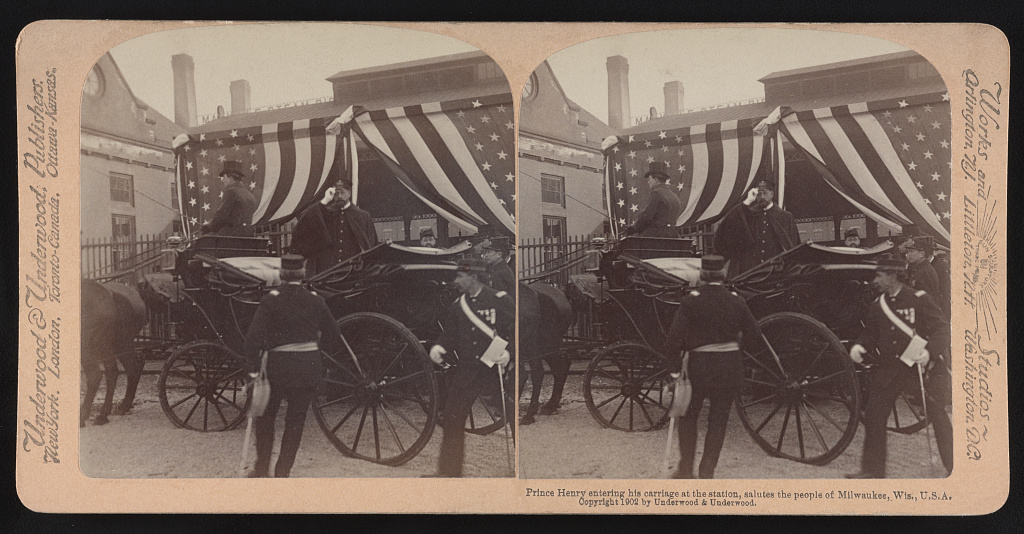

As the city grew into a major economic and cultural center in the mid-nineteenth to early twentieth century, Milwaukee hosted several major organizational and industrial conventions. The city’s significant German population particularly supported meetings of German cultural organizations, such as Sängerfests and Turnfests, which drew visitors to Milwaukee from throughout the state, nation, and even abroad.[3] From 1881 to 1902, the Merchants Association and Chamber of Commerce hosted an annual Industrial Exposition in Milwaukee that showcased the city’s manufacturers to visitors from around the region.[4] In 1892, West Allis (then called North Greenfield) became the permanent home of the Wisconsin State Fair, which brought both farmers and tourists to the Milwaukee area.[5] The city also accommodated national encampments and conventions of veterans’ organizations, including the Grand Army of the Republic and the American Legion.

Milwaukee’s business interests helped finance early visitor accommodations and infrastructure and sponsored major events. For instance, pioneer grain trader Daniel Newhall, local meatpacker John Plankinton, and Charles Pfister, son of local tanning magnate Guido Pfister, established notable hotels in downtown Milwaukee in the mid-to-late nineteenth century. Plankinton, Frederick Pabst, and other Milwaukee business leaders guided construction of an exposition building that hosted the city’s annual Industrial Exposition and other major events from 1881 until it was destroyed by fire in 1905.[6] Major brewers Pabst, Schlitz, Blatz, and Miller were especially significant players in the city’s developing tourist industry, opening lavish beer gardens, amusement parks, beer halls, theaters, restaurants, and hotels that served as major attractions in the late-nineteenth and early twentieth century.[7]

Coming to understand the benefit of convention traffic to the city’s economy, local business interests increasingly organized their efforts to attract these events to Milwaukee. In addition to the Merchants Association and the Chamber of Commerce, the Milwaukee Advancement Association and Citizens’ Business League, organized in 1888 and 1897 respectively, promoted the city as a convention site.[8] These groups and other independent companies published guidebooks, postcards, and souvenir items highlighting significant Milwaukee landmarks for visitors.[9] Claiming Milwaukee as “the ‘Bright Spot’ convention city of all America,” a 1902 Citizens’ Business League souvenir book boasted that “conventions—National and State, great and small—follow in close succession in Milwaukee” every year.[10] In 1938, the Milwaukee Association of Commerce reported that the previous year’s 365 conventions, amidst the Great Depression, drew 114,000 people and $6.5 million in additional revenue to the city.[11]

City officials also played an increasingly significant role in developing and coordinating resources for the tourist industry in the early twentieth century. Mayor David S. Rose famously helped make Milwaukee “wide-open” to gambling, prostitution, and other vice businesses that served convention-goers.[12] Subsequent Socialist administrations worked to clean up such operations while supporting large public projects to help bolster the city’s national appeal.[13] In 1909, city officials collaborated with business interests to build the Milwaukee Auditorium on the site of the former Exposition Building. The new structure accommodated numerous local and national conventions, exhibitions, political rallies, concerts, circuses, and other major attractions until it was redeveloped into a theater in the early 2000s.[14]

As commercial activity moved into the suburbs and Milwaukee’s infrastructure deteriorated in the mid-twentieth century, major businesses within the city focused efforts to modernize downtown. The 1948 Corporation (later the Greater Milwaukee Committee), for instance, lobbied for the construction of a new professional baseball stadium, sports arena, museum, zoo, and civic center as well as expanded highways and parking facilities.[15]

From 1960 to 1988, Mayor Henry Maier’s administration fostered public-private partnerships that made tourism a key player in Milwaukee’s economy. After a trip to West Germany in 1961, Maier envisioned the creation of a “world-class festival” in Milwaukee on par with Munich’s Oktoberfest that would draw tourists from throughout the world. In 1967, Maier organized Milwaukee World Festival, Inc., a non-profit organization of business, civic, and labor leaders that launched the city’s annual Summerfest in 1968.[16] Renting the festival’s current lakefront site from the city, Summerfest and its associated events claimed to attract 1.5 million people and $180 million in revenue to the Milwaukee area every year by the early 2010s.[17] The Maier administration also helped coordinate the construction of a modern downtown convention center, which opened as part of the Milwaukee Exposition and Convention Center and Arena (MECCA) complex in 1974.[18] In the 1980s, the Maier administration collaborated with business interests and developers to redevelop several historic downtown buildings into the Grand Avenue Mall and construct a Riverwalk along the Milwaukee River—projects similar to tourist attractions in other cities.[19]

In 1967, the Greater Milwaukee Conventions and Visitors Bureau (now VISIT Milwaukee) split off from the Milwaukee Association of Commerce as a non-profit organization to market the city as a tourist destination with funding from local hotel tax revenue.[20] In 1984, the bureau introduced an official slogan, “Milwaukee: A Great Place on a Great Lake,” and accompanying logo of an “M” in the shape of waves.[21] The organization’s more recent logo includes a likeness of the Milwaukee Art Museum’s Calatrava addition.[22]

Some neighborhoods also saw tourism as a potential boon to their commercial districts in the late twentieth century. Water Street, Brady Street, Bay View, and other areas worked to become major “nightlife hotspots” that might draw visitors.[23] Historic Walker’s Point, Inc. (later Historic Milwaukee, Inc.) organized in 1973 to turn the near south side neighborhood into a historic district and tourist destination akin to Philadelphia’s Society Hill, the New Orleans French Quarter, and Georgetown in Washington, DC.[24]

Major businesses also continued to work independently to draw visitors to Milwaukee in the late-twentieth and early twenty-first century. The Schlitz Brewing Company sponsored the annual Great Circus Parade in conjunction with the Circus World Museum in Baraboo from 1963 to 1973, a venture that returned sporadically in the 1980s through 2000s.[25] Harley-Davidson hosted a major rally in Milwaukee in honor of its centennial anniversary in 2003, drawing over 200,000 motorcycle riders from around the world.[26] The company repeated these celebrations for its 105th and 110th anniversaries and opened a museum in the Menomonee River Valley in 2008.[27] The annual meeting of Northwestern Mutual Life Insurance Company draws thousands of company representatives to Milwaukee from throughout the United States every summer, bringing in nearly $13 million to the local economy by 2015.[28]

A more modern Midwest Airlines Center (now the Wisconsin Center) replaced the MECCA Convention Center in 1998.[29] Miller Park and the Milwaukee Art Museum’s Calatrava addition, both constructed with public and private funding, quickly became iconic destinations after they opened three years later.[30] In 1991, the Forest County Potawatomi opened a bingo and casino facility in the Menomonee River Valley. Major expansions in the 2000s and 2010s added a theater, event center, and hotel, drawing an estimated 6 million visitors to the complex every year—revenue shared with the city and county.[31]

The attraction of visitors and conventions has certainly been a key focus of the city’s civic and business leaders throughout nineteenth and twentieth century. This growing and evolving tourist industry is proving to be a progressively important part of the city’s economy as Milwaukee has gained new and increasing attention as a national and international destination in the twenty-first century.[32]

Footnotes [+]

- ^ There is some confusion over Milwaukee’s first hotel. Bayrd Still credits John and Luther Childs with establishing the Cottage Inn as the city’s first hotel but does not provide a date. James S. Buck, William George Bruce, and John G. Gregory agree that Jacques Vieau formed the city’s first hotel in 1835 and that the Childs’ establishment followed in 1836. Bruce refers to Vieau’s hotel as “The Triangle.” However, both Buck and Gregory explain that this was a local nickname for the establishment due to the triangle bell on its roof, and Vieau’s establishment was in fact the Cottage Inn, taken over by the Childs brothers in 1836. James S. Buck, Pioneer History of Milwaukee: From the First American Settlement in 1833 to 1841 (Milwaukee: Swain & Tate, 1890), 65-67; William George Bruce, History of Milwaukee, City and County, vol. 1 (S. J. Clarke Publishing Company, 1922), 195; John G. Gregory, History of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, vols. 1 and 2 (Chicago and Milwaukee: S.J. Clarke Publishing, 1931), 1: 68, 2: 679-688; Bayrd Still, Milwaukee: The History of a City (Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1948), 65-66.

- ^ Gregory, History of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, 2: 687-688; Still, Milwaukee, 65.

- ^ Bruce, History of Milwaukee, 677; Heike Bungert, “Demonstrating the Values of ‘Gemütlichkeit’ and ‘Cultur’: The Festivals of German Americans in Milwaukee, 1870-1910,” in Celebrating Ethnicity and Nation: American Festive Culture from the Revolution to the Early Twentieth Century, ed. Jürgen Heideking, Geneviève Fabre, and Kai Dreisbach (New York: Berghahn Books, 2001), 180-181; “Turnfest in Milwaukee: Great Celebration of the North American Turnerbund,” New York Times, July 10, 1893, 2; “The Milwaukee Saengerfest,” New York Times, June 30, 1879, 1; “National Saengerfest: Great Crowds Assembling at Milwaukee for the Festival,” New York Times, July 21, 1886, 1.

- ^ Still, Milwaukee, 347; Gregory, History of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, 1:495-506.

- ^ John Gurda, Cream City Chronicles: Stories of Milwaukee’s Past (Madison: Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 2014), 265-267.

- ^ Still, Milwaukee, 347; Gregory, History of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, 1:500; Jeff Beutner, “Yesterday’s Milwaukee: Milwaukee Industrial Exposition Building, 1880s,” Urban Milwaukee, August 18, 2015.

- ^ Still, Milwaukee, 403-404; Thomas C. Cochran, The Pabst Brewing Company: The History of an American Business (New York: New York University Press, 1948), 143-146, 210-213, 223, 226-227, 256-258; Harry H. Anderson, “Recreation, Entertainment, and Open Space: Park Traditions in Milwaukee County,” in Trading Post to Metropolis: Milwaukee County’s First 150 Years, ed. Ralph M. Aderman (Milwaukee: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 1987), 260-262; Uwe Spiekermann, “Marketing Milwaukee: Schlitz and the Making of a National Beer Brand, 1880-1940,” Bulletin of the German Historical Institute, no. 53 (Fall 2013): 57.

- ^ Bayrd Still, “Milwaukee, 1870-1900: The Emergence of a Metropolis,” The Wisconsin Magazine of History 23, no. 2 (December 1939): 149-151; Bayrd Still, “The Development of Milwaukee in the Early Metropolitan Period,” The Wisconsin Magazine of History 25, no. 3 (March 1942): 299.

- ^ Examples include: S. H. Knox & Co., Souvenir of Milwaukee, Wis. (New York: W. J. MacFarlane, 1890); R.B. Watrous, Milwaukee: A Bright Spot (Milwaukee: Citizens’ Business League, 1902); “Greetings From Milwaukee: Selections from the Thomas and Jean Ross Bliffert Postcard Collection,” University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Libraries, Digital Collections, accessed August 24, 2015.

- ^ Watrous, Milwaukee, 3.

- ^ Milwaukee Association of Commerce, “Seventy-Seventh Annual Meeting and Dinner” February 8, 1938, Mss 0777, Folder 3, Milwaukee County Historical Society; Still reported similar numbers for 1940 in Milwaukee, 509.

- ^ Gurda, Cream City Chronicles, 205.

- ^ Gurda, Cream City Chronicles, 201, 206-207.

- ^ Still, Milwaukee, 347; Bruce, History of Milwaukee, 421-432; Gurda, Cream City Chronicles, 157-159.

- ^ Eric Fure-Slocum, Contesting the Postwar City: Working-Class and Growth Politics in 1940s Milwaukee (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 221-229, 261; John M. McCarthy, Making Milwaukee Mightier: Planning and the Politics of Growth, 1910-1960 (DeKalb, IL: Northern Illinois University Press, 2009), 125-126, 138; Joseph A. Rodriguez, Bootstrap New Urbanism: Design, Race, and Redevelopment in Milwaukee (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2014), 32-33; Jack Norman, “Congenial Milwaukee: A Segregated City,” in Unequal Partnerships: The Political Economy of Urban Redevelopment in Postwar America, ed. Gregory D. Squires (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1989), 182-183.

- ^ “Maier Studies International Festival Here,” Milwaukee Sentinel, November 3, 1961, 13; Rodriguez, Bootstrap New Urbanism, 74-75; “A General Proposal for a Milwaukee World Festival” (Milwaukee: Prospectus Committee, World Festival Planning Group, April 4, 1964).

- ^ “Milwaukee World Festival, Inc. Fact Sheet,” Urban Milwaukee, May 10, 2013.

- ^ John Gurda, The Making of Milwaukee (Milwaukee: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 1999), 407-408; Joseph J. Korom Jr., Look Up, Milwaukee: Eastside/Westside, All Around Downtown, A Descriptive and Pictorial Display of Selected Architectural Scenery (Milwaukee: Franklin Publishers, 1979), 108.

- ^ Rodriguez, Bootstrap New Urbanism, 63-64; Gurda, Making of Milwaukee, 406, 413.

- ^ “History of Convention & Visitors Bureau of Milwaukee,” Visit Milwaukee, accessed August 22, 2015.

- ^ “A Great Place,” Milwaukee Journal, May 29, 1984, sec. 1, 14.

- ^ “Visit Milwaukee,” VISIT Milwaukee, accessed August 26, 2015.

- ^ Rodriguez, Bootstrap New Urbanism, 112-113.

- ^ “Rebirth of an Historic Community” n.d., box 1, folder 10, and “Notes on Financial Benefits of Preservation Districts” November 16, 1974, box 2, folder 17, both in Historic Milwaukee, Inc., Records, UWM Mss 133, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Libraries, Archives Department.

- ^ Charles Philip Fox, America’s Great Circus Parade: Its Roots, Its Revival, Its Revelry (Greendale, WI: Reiman Publications, 1993), 7; “Great Circus Parade Returns to Milwaukee after Six Years,” USA Today, June 29, 2009.

- ^ Graeme Zielinski, “Ears Ringing, We Wave Goodbye,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, September 2, 2003, sec. B, 1.

- ^ “Photos: Harley-Davidson 105th Anniversary Celebration,” JSOline http://www.jsonline.com/multimedia/photos/28695549.html, last accessed August 26, 2015; “Harley-Davidson Motorcycle 110th Anniversary News, ” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, accessed August 26, 2015; Rodriguez, Bootstrap New Urbanism, 124-126; Gurda, Making of Milwaukee, 414.

- ^ “‘We Are Thrilled:’ Northwestern Mutual’s Annual Meeting to Draw 10,000 to Milwaukee,” FOX6Now.com, July 16, 2015.

- ^ Gurda, Making of Milwaukee, 412-413.

- ^ Gurda, Making of Milwaukee, 413; Bruce Murphy, “Little Things Add up for Art Museum,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, July 28, 2003, sec. 1, 1, 5; Martin J. Greenberg, “The Economics of Miller Park,” JSOnline, April 5, 2012.

- ^ “Our History: Building on Tradition,” Potawatomi Hotel and Casino, accessed August 26, 2015; Cary Spivak, “Potawatomi Casino Sees Modest Increase in Revenue,” JSOnline, August 17, 2015; Gurda, Making of Milwaukee, 414.

- ^ “Articles on Milwaukee,” VISIT Milwaukee, accessed August 26, 2015.

For Further Reading

Rodriguez, Joseph A. Bootstrap New Urbanism: Design, Race, and Redevelopment in Milwaukee. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2014.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.