The Historic Third Ward, often known simply as the “Third Ward,” is a neighborhood within the City of Milwaukee. It lies mostly south of Interstate 794, between the Milwaukee River and Lake Michigan.[1] In 1984, seventy-one buildings, spanning more than a dozen city blocks, were accepted by the National Register of Historic Places as “The Historic Third Ward District.”[2]

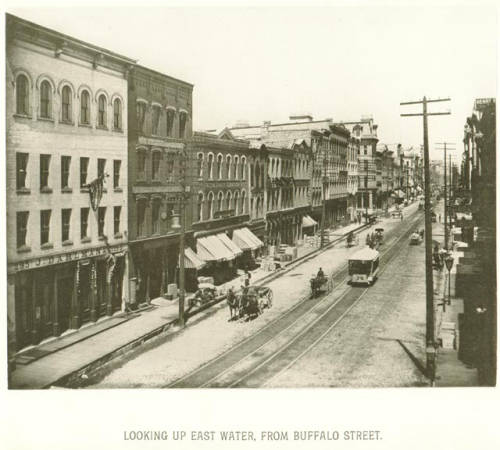

After Native Americans ceded the land in 1833, Solomon Juneau and Morgan Martin purchased the property. It was marshy, but the convenient location on the river and lake suited it for warehouses and businesses. As Juneau and Martin resold commercial land and residential lots, the Third Ward quickly became an Irish neighborhood. The immigrants came either directly from Ireland during the potato famine or by way of Massachusetts following a slump in the economy that closed many cotton mills. Area businesses were eager to hire inexpensive immigrant labor. The neighborhood’s reputation for rowdy behavior gave it the nickname “the Bloody Third.”[3]

The neighborhood’s ethnic makeup changed dramatically after the fire of 1892. At least twenty blocks and more than 440 buildings burned. Almost 2,500 people were left homeless. The Irish largely relocated to other parts of the city. The Third Ward was rebuilt in time for a large wave of Italian settlement. The Blessed Virgin of Pompeii church was the hub of the community until it was razed in 1967 to make room for a freeway.[4] The Italian Community Center opened on Chicago Street in 1990.[5]

The Summerfest grounds, renamed Henry Maier Festival Park in 1986, opened at the neighborhood’s eastern edge in 1970. It consists of seventy-five acres of land and is the home of what is billed as “the world’s largest music festival.” The park also hosts several ethnic festivals including Festa Italiana, Indian Summer, Irish Fest, German Fest, Mexican Fiesta, and Polish Fest.[6] The annual PrideFest claims to be the largest volunteer-run celebration of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender culture and community taking place on a permanent site in the United States.[7] Lakeshore State Park, Wisconsin’s only urban state park, opened in 2007 and connects Maier Festival Park to the Discovery World science and technology museum.[8]

The Historic Third Ward’s gentrification began in the late 1970s. Dozens of factories and warehouses were converted to condominiums, loft apartments, restaurants, bars, art galleries, and specialty shops. North Broadway is the center of the Third Ward’s shopping, dining, and fine arts options. [9] The Milwaukee Institute of Art and Design anchors the southern end of the street at Catalono Square.[10] The Milwaukee Public Market, opened in 2005, marks the northern end of the Third Ward’s segment of Broadway.[11]

Like other gentrified urban neighborhoods, the Third Ward attracts affluent people without children. Census tract 1874 covers the entire populated portion of the Third Ward and part of the nearby Harborview/Walker’s Point neighborhood. Recent census estimates of median household income for the tract are almost twice that of the city of Milwaukee (almost $80,000 compared to almost $41,000 for the city).[12] While almost 34% of Milwaukee households had someone aged 18 or younger, in tract 1874, only 4% of households had a member aged 18 or younger.[13] 73% of the population in tract 1874 aged 25 or more had bachelor’s or higher degrees, compared to 23% for the city.[14]

Footnotes [+]

- ^ City of Milwaukee, “Milwaukee Neighborhoods,” May 2000, http://milwaukee.gov/ImageLibrary/Public/ map4.pdf, last accessed June 27, 2015, now available at http://www.ci.mil.wi.us/ImageLibrary/Public/map4.pdf, last accessed August 28, 2017.

- ^ “Take a Tour,” Historic Third Ward website, last accessed June 27, 2015.

- ^ John Gurda, The Making of Milwaukee, 3rd ed. (Milwaukee: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 2008), 175; Spaces and Traces: Third Ward Classics & Urban Chic (Milwaukee: Historic Milwaukee, Inc., 2009), 8-9.

- ^ Gurda, The Making of Milwaukee, 175-176, 335; Spaces and Traces: Third Ward Classics & Urban Chic, 10-11.

- ^ Gurda, The Making of Milwaukee, 404; “The Italian Community Center and Festa Italiana,” The Italian Community Center website, last accessed June 27, 2015.

- ^ Gurda, The Making of Milwaukee, 403-404; “History of Summerfest,” last accessed June 27, 2015; and Milwaukee World Festival, Inc. website, last accessed June 27, 2015.

- ^ “About,” Milwaukee Pride, Inc. website, last accessed June 27, 2015.

- ^ Friends of Lakeshore State Park website, last accessed June 27, 2015.

- ^ Gurda, The Making of Milwaukee, 366-367, 393; Historic Third Ward website, last accessed June 27, 2015; Spaces and Traces: Third Ward Classics & Urban Chic, 11.

- ^ Milwaukee Institute of Art and Design website, last accessed June 27, 2015.

- ^ Gurda, The Making of Milwaukee, 413.

- ^ U.S. Census Bureau, Income in the Past 12 Months (In 2014 Inflation-Adjusted Dollars), S1901, 2010-2014 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates.

- ^ U.S. Census Bureau, Households and Families, S1101, 2010-2014 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates.

- ^ U.S. Census Bureau, Educational Attainment, S1501, 2010-2014 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates.

For Further Reading

Gurda, John. The Making of Milwaukee. 3rd ed. Milwaukee: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 2008.

Klancnik, Fred, and William Brose. “Lakefront Renaissance.” Civil Engineering (June 2010): 63-73, 93.

Spaces and Traces: Historic Third Ward. Milwaukee: Historic Milwaukee, Inc., 1998.

Spaces and Traces: Third Ward Classics & Urban Chic. Milwaukee: Historic Milwaukee, Inc., 2009.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.