Since Milwaukee’s earliest days, organized indoor recreation has promoted fitness, hygiene, entertainment, and civic betterment. While a wide variety of Milwaukeeans participated in these activities, there were noticeable class, gender, and age distinctions that often reflected the deeper social goals at work.

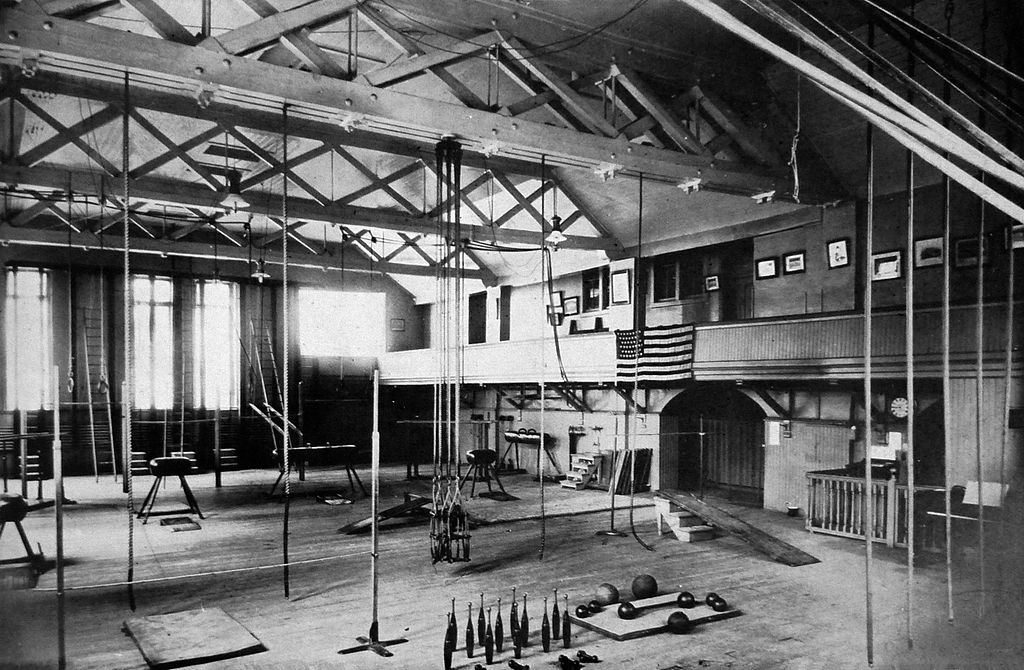

The earliest references to indoor recreation in Milwaukee date to the 1850s and involve the Turnverein, or Turners, as they are known today. Their roots stretch back to early nineteenth century Germany, where gymnastics training prepared the bodies of young Germans to resist Napoleonic domination. The movement inspired by the Turners played a major role in the German revolution of 1848. While the revolution was ultimately defeated, many of those exiled in its aftermath brought the Turner tradition to the United States.[1]

In April 1850, the Milwaukee Sentinel reported that a Mr. Schultz would soon be opening a Turner-inspired gymnasium, located in the rear of Mozart Hall on Spring Street (today West Wisconsin Avenue). Schultz had been a soldier during the German revolution and hoped that Turners’ exercise programs might also boost the bodies and minds of Milwaukee’s boys.[2] The first true Turner Hall was constructed in 1855 on North Fourth Street.[3] This building was replaced in 1882 with the West Side Turner Hall, which still stands today at 1034 North Fourth Street. This building’s beer hall, lecture and meeting rooms, and grand ballroom indicated the group’s social significance and highlighted the Turners’ activism in political and social justice issues.[4]

Indoor roller skating debuted in Milwaukee around the same time the first Turner Hall was opened. The city’s first roller rink was standing on the site of what it today the Milwaukee Theatre by 1855.[5] This building was replaced in 1868 by the West Side Market Hall, which housed a music hall, a farmer’s market, and one of the largest skating rinks in the country. The rink covered over 20,000 square feet and could accommodate 1,000 skaters.[6] In the winter months, the hall hosted ice skating and curling.[7] Despite its innovations, the hall had a fairly short lifespan. As the popularity of roller skating waned—and with plenty of space for ice skating on the city’s rivers and Lake Michigan—the hall closed in 1872 and was razed in 1880.[8]

Replacing the Market Hall in 1881 was the $300,000 Exposition Building. Used primarily for concerts and conventions, the building also had a section dedicated to roller and ice skating.[9] Privately-funded, the building was erected with the civic-minded backing of a group that would later be called the Merchants and Manufacturers’ Association of Milwaukee and the Chamber of Commerce.[10] The inclusion of space for public recreation within this building foreshadowed a larger movement to come that promoted physical activity as a means of community betterment.

In 1887, the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA), founded locally in 1858 by Protestant church leaders, opened a facility on North Fourth Street. The new building allowed the group to offer indoor physical activities and featured a bowling alley, pool, and gymnasium.[11] In 1892, the local Young Women’s Christian Association was founded, although the group did not open its own facility until 1930.[12]

Another prominent example of city leaders promoting indoor recreation emerged in the late 1880s as the city announced plans for the construction of several public natatoriums. The pools provided a place for swimming during the winter months and an alternative to swimming in the often-polluted rivers and Lake Michigan in the summer. They also provided a facility for indoor bathing to the large portion of Milwaukee residents without access to clean water.[13] People without skin diseases were free to clean themselves in the pool, but the use of soap was limited to the locker room showers.[14] The first public natatorium opened in 1890 at Prairie (now West Highland) and North Seventh streets.[15] Nearly 130,000 people visited the facility during its first year of operation.[16] By 1903, the city had opened two more natatoriums and was, at the time, second only to Philadelphia in the number of public indoor pools enjoyed by city residents.[17]

Milwaukee’s early natatorium patrons were segregated by gender. At the Prairie Street pool, women and girls were only allowed to use the facilities on Wednesdays and Fridays.[18] Men and boys swam naked while girls and women wore heavy cotton or flannel suits.[19] Despite the intentions of those who promoted natatoriums as a supporter of good public hygiene, most of the boys in attendance were more interested in horseplay than bathing.[20]

By 1914, there were five public natatoriums in various wards of the city that accommodated about 1.2 million bathers per year. Attendance was still segregated by gender and, in certain circumstances, by age and employment status. To avoid the still-rambunctious crowds of boys who were the natatorium’s most regular patrons, one day per week in the summer months was reserved exclusively for the use of employed men. The attendance of girls and women at the pools, still limited to two days per week, lagged far behind that of boys and men. A 1914 City Club report on recreation in the city said that women made up between 5 and 12 percent of the attendees at the various city natatoriums. Few commentators at the time promoted physical activity for females.[21]

Indeed, as the City Club reported on recreation programs and facilities as a potential means of social betterment, they focused almost entirely on Milwaukee’s boys. “One of the best ways to reform an unruly gang,” the Club concluded, “is to get them to become devoted to [being] a vigorous, manly man.”[22] Aside from the natatoriums, the indoor facilities of eight youth social clubs operated in city schools were touted as a way of keeping Milwaukee’s sometimes troublesome boys in line. Activities at these clubs were strictly divided along gender lines, with girls learning cooking while boys competed in athletic contests. Medicine balls exercises and indoor baseball games were held. Each club even had a designated “roughhouse room” which was “set aside for the expression and exhaustion of animal spirits.” As many as 60,000 young people, mostly boys, visited these centers annually, where “the exuberance which might otherwise go into disturbance, is expended in body-building sport.”[23]

Despite the prejudices of the time, girls were not entirely shut out from indoor athletic competition. In 1897, Stella Burnham opened a gymnasium for girls and women in the McGeoch Building at 322 East Michigan, relocating it from a temporary site in the old Union Baptist Church building on North Jefferson Street.[24] Burnham was also the city’s first women’s swimming instructor—one of the few women’s instructors in the nation at the time—teaching classes at the south side natatorium. But even Burnham seemed resigned to the thinking of the day, telling the Milwaukee Journal that only “exceptionally strong” women were capable of swimming and that a woman who spends too much time in the water ran the risk of it having a “debilitating effect” on her.[25]

Burnham also coached and organized some of the first women’s basketball games in the city, first held at the old Baptist church in 1896.[26] But Burnham quickly dropped the game from her teachings, feeling that such competition was beyond the bounds of good taste. After a 1901 exhibition between the East Division High School girls and a high school team from Waukesha at her Michigan Street gymnasium, she joined the chorus of those condemning the idea of girls’ athletics as a public spectacle. “I base my objections to the game on the ground of the over-exertion entailed,” she told the Milwaukee Sentinel, “the mental effect such exertion has on girls who are at school and the demoralizing results that come when the game is carried too far. We don’t want all the bloom rubbed off the peach, you know.”[27]

At the time, the only females allowed to use the facilities of the Milwaukee Athletic Club (MAC) were the wives and daughters of its male members.[28] Founded in 1882 for the purpose of “developing of the bodily powers through gymnastic[s] and exercises,” the MAC operated in a number of downtown facilities in the decades that followed, each consisting of a gymnasium and little else. In 1917, the MAC opened its present-day twelve-story building at Broadway and Mason Street. One year later, club policy was finally amended to allow women to become members. However, the new facility also saw a change in the club’s focus from training elite athletes to a providing an exclusive social club where the city’s business elite could exercise or make use of the club’s dining rooms, bar, barber shop, or meeting halls.[29]

If the city’s elite had the MAC building for socializing through indoor recreation, the working classes had the dozens of bowling alleys that began to appear in the city in the early 1900s. By the turn of the century, the Langry-McBride Alleys and Saloon boasted 24 lanes in the basement of a building at 307 S. Second St. In 1917, the Plankinton Arcade was opened just across the street, featuring 41 lanes, as well as 60 billiard tables and a rifle range, in what was promoted as “the world’s largest indoor amusement and recreation parlor.” By the 1920s, alleys were featured in many social clubs (including the MAC), hotels, and theaters.[30]

But the heart of bowling in Milwaukee was always the numerous bars and taverns that featured lanes. By 1927, the city was home to nearly 50 bowling alleys.[31] League bowling attracted thousands of participants, including a number of women. The first women’s league formed in 1916, at a time when taverns and barrooms were not considered to be appropriate places for women to congregate.[32] Women’s bowling leagues were a staple of many alleys by the 1920s, becoming one of the earliest instances of women’s indoor recreation entering the city’s mainstream.[33]

Indoor ice skating briefly had a palatial home in Milwaukee in the 1920s at the Castle Ice Gardens at 35th and Wells. Opening in 1922, it was promoted as “one of the finest ice rinks” in America and featured competitive ice hockey as well as recreational skating. Unlike previous indoor rinks, the Castle Ice Gardens was open year-round, using a refrigeration system to keep the ice frozen in the summer months.[34] The enterprise proved costly, however, and the place was shuttered in 1924 for financial reasons.[35]

Indoor roller skating proved to be a less risky venture than ice skating and prospered at a number of locations in the pre-war years. The Riverside Roller Rink operated out of a tent when it opened in 1900. By 1909, the rink had a permanent home at 305 E. North Ave. After this building was destroyed by a fire in 1929, it was rebuilt and remained in operation until 1961.[36] The Palomar Roller Rink opened on South Twenty-Seventh Street in 1939 and was soon averaging between 700-900 skaters per day.[37]

After the Second World War, a renewed effort to use recreation as a means of combating juvenile crime was seen in the expansion of County Park programs to include indoor activities in their programming. The Parks Department started organized athletics programs in 1935 but did not offer indoor recreational activities until 1946.[38] That year, community centers were opened in pavilions or buildings at Brown Deer, Sherman, Smith, and South Shore parks. These centers were open to young people one to two days per week and offered dancing, checkers, card playing, and other light activities.[39] Most popular at the parks, however, was table tennis. By 1951, similar centers were added in Garfield, Jackson, and Sheridan parks, with most operating five or more days per week in the winter months.[40] The following year, a winter table tennis tournament was held at the Lake Park Pavilion. 32,000 Milwaukee youths played Parks Department table tennis that year, and the game had become so popular that exclusive hours were set aside every evening at the Lake Park Pavilion for matches.[41]

Also serving Milwaukee’s young people was the Milwaukee Boys’ Club. Founded in 1887, the club initially focused on outdoor recreation, but began to open facilities for indoor activities in the 1950s. By 1984—when it was renamed the Milwaukee Boys & Girls’ Club—it had five facilities located in the central city, offering an alternative to the streets for some of Milwaukee’s most disadvantaged areas, with basketball programs, dances, ping-pong, pool, and computer classes. [42]

While indoor recreation at County Parks and the Boys’ Club flourished, attendance at the old city-run natatoriums was declining. By 1948, all seven of the city’s natatoriums remained in use, but overall use of the facilities had fallen by 50 percent since 1933.[43] The Jackson Street Natatorium was closed in 1958. The Highland Natatorium, the first in the city, followed in 1964. With rising costs and declining revenues, the city sought to modernize the old buildings or replace them with modern indoor pools.[44] In 1977, the year the South Fourth Street natatorium closed, the county opened an indoor pool at Pulaski Park and soon after added similar facilities at Moody and Noyes parks.[45] Each of the five remaining public natatoriums closed in the 1980s.[46]

Post-war Milwaukee saw shifts in population that changed the way the city’s recreation facilities were used, and indoor games both familiar and new prospered during this era. Summertime indoor ice skating reappeared in 1954 after a twenty-year absence, with a rink installed in the Milwaukee Arena, which had otherwise been mostly idle in the warmer months.[47] In 1970, the first County-operated indoor rink opened at Wilson Park on South Twentieth Street for skating and ice hockey. The rink was the same size as a professional hockey rink and was housed in a small arena that also featured seating for 2,500 and a swimming pool.[48]

Perhaps no building represented the changes of Milwaukee’s post-war era as much as Wauwatosa’s Mayfair Mall, opened in 1958. The mall signaled the beginning of the shift of the area’s commercial center from the city to the suburbs and, with the addition of an indoor skating rink during a massive 1973 expansion of the facility, the shift of major recreational centers as well.[49] The Mayfair Ice Chalet, as it was dubbed, proved to so popular that some mall tenants felt it was a revenue-reducing distraction. Despite being the busiest mall rink in the nation from 1984 to 1985, the Chalet was removed in 1986.[50]

Roller skating also made a return in the postwar years, peaking as a fad in the late 1970s and early 1980s. By 1979, there were a half-dozen rinks in the Milwaukee metro area. While outdoor skating was popular with college-aged people and adults, one rink operator estimated that 80 percent of indoor skaters were between the ages of six and 15. The spike in popularity of skating among the younger set helped to offset the bad reputation roller rinks had developed in the mid-1970s as a spot for underage drinking and smoking and a hangout for young criminals.[51] In 1980, Wisconsin Skate University, a skating social and instructional club, opened the Palace Roller Rink at Port Washington Road and Capital Drive in Milwaukee. The rink was the area’s finest, with an arcade, dance floor, and room for 2,000 skaters.[52]

Appealing to a much different demographic was the Milwaukee River Hills Tennis Club, one of several indoor tennis clubs in the area by the mid-1960s. The River Hills club dated back to 1937, when a local tennis enthusiast built an indoor court for his wife. The novelty of indoor tennis proved so popular among the couple’s friends that in 1952, the facility was converted into a private club. In the mid-1960s, the Milwaukee Indoor Tennis club opened in Glendale and the Brook Club opened in Brookfield.[53]

Milwaukee area bowling also followed the trend to the suburbs with the opening of the Bowlero in Wauwatosa in 1958. Originally housing 48 lanes, Bowlero grew to 72 lanes in 1960 and was the largest bowling center in the area for many years. As late as 1980, it was estimated that nearly ten percent of Milwaukee County’s 965,000 population were regular bowlers.[54]

Recent years have seen Milwaukeeans enjoy indoor recreation in ways both new and old. At Turner Hall, the concept of betterment through physical exercise is still encouraged with gymnastics classes, as well as fencing, rock climbing, and yoga.[55] Bowling remains a popular activity, with part-time and league bowlers competing at newer complexes, as well as century-old lanes like those at Riverwest’s Falcon Bowl and Lincoln Avenue’s Holler House, home to the oldest certified lanes in the country.[56]

Recreational indoor ice skating is still held year-round at Wilson Park. At the Pettit National Ice Center, opened in 1992, both recreational and competitive skaters take the ice, as do numerous youth and adult hockey teams.[57] County facilities, including pools at Noyes and Pulaski parks, host multiple indoor sports, including basketball, boxing, and volleyball.[58] Table tennis made a comeback when Spin Milwaukee (now known as Evolution Milwaukee) opened in the Third Ward in 2010 as a ping-pong gastropub.[59]

The spike in popularity of soccer, both youth and adult, led to the opening of a number of indoor fields, including the massive Brookfield Indoor Soccer Complex, which covers 80,000 square feet and three artificial surface fields.[60] Laser tag and paintball also made gains in recent decades as indoor recreations. Paintball Dave’s, located on Broadway in the Third Ward, opened in 1988 and bills itself as the oldest indoor paintball field in the world.[61]

As the bulk of Milwaukee’s indoor recreation shifted away from being city-sponsored and managed by not-for-profit entities, both the age and gender restrictions, as well as the deeper social goals promoted by their creation, have mostly fallen by the wayside. Class restrictions remain in play, however, even as free and subsidized activities ensure access to indoor recreation for Milwaukeeans of all means. Still, indoor recreation remains a visible and vital part of the city’s social fabric.

Footnotes [+]

- ^ “History of the Milwaukee Turners,” Milwaukee Turners website, accessed October 23, 2014.

- ^ “Gymnasium,” Milwaukee Sentinel, April 27, 1850, p. 2.

- ^ “Turners to Celebrate 85th Year Saturday,” Milwaukee Journal, June 16, 1938, p. 16.

- ^ “History of the Milwaukee Turners.”

- ^ “Exposition Building, 1881-1905,” Manuscript Collections page, Milwaukee County Historical Society website, accessed October 12, 2014.

- ^ “The Skating Rink,” Milwaukee Sentinel, October 17, 1867, p. 1.

- ^ “The Skating Rink,” Milwaukee Sentinel, December 25, 1867, p. 1.

- ^ Charles House, “City Burghers Razed Market Hall, Replaced It with Exposition Building,” Milwaukee Sentinel, April 8, 1950, p. 18.

- ^ “State News,” Wisconsin State Journal, February 1, 1884, p. 2; “Roller Rink to Open,” Wisconsin Weekly Advocate, October 30, 1902, p. 3.

- ^ John Hoving, “Father of Auditorium Was 1881 Exposition,” Milwaukee Journal, April 19, 1950, part 3, p. 12.

- ^ James I. Clark, 100 Years of Service to Youth: A History of the Young Men’s Christian Association of Milwaukee, Wisconsin (Milwaukee: The Association, 1958), p. 6-7.

- ^ “Biography/History,” Young Women’s Christian Association Records, 1892-1961, University of Wisconsin Digital Collections, accessed November 1, 2014.

- ^ “Remember When the Public Natatorium Was a Bath House,” Milwaukee Journal Green Sheet, September 5, 1984, p. 1.

- ^ “City Brevities,” Milwaukee Sentinel, February 9, 1890, p. 3.

- ^ “Highland Avenue Natatorium,” Old Milwaukee website, accessed November 4, 2014.

- ^ George A. Dundon, “Health Chronology of Milwaukee,” Milwaukee Health Department, 1941, Children in Urban America Project website, accessed October 21, 2014.

- ^ Jeff Wiltse, Contested Waters: A Social History of Swimming Pools in America (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2007), p. 26-29.

- ^ “City Brevities,” Milwaukee Sentinel, February 9, 1890, p. 3.

- ^ “Milwaukee Women Take to the Water,” Milwaukee Journal, June 27, 1902, p. 7.

- ^ Wiltse, Contested Waters, p. 26-29.

- ^ Marion G. Ogden, “Amusement and Recreation in Milwaukee: Municipal Recreation, A Bulletin of the City Club, 1914,” Children in Urban America Project website, accessed October 16, 2014.

- ^ Marion G. Ogden, “Amusement and Recreation in Milwaukee: Municipal Recreation, A Bulletin of the City Club, 1914,” Children in Urban America Project website, accessed October 16, 2014.

- ^ Marion G. Ogden, “Amusement and Recreation in Milwaukee: Municipal Recreation, A Bulletin of the City Club, 1914,” Children in Urban America Project website, accessed October 16, 2014.

- ^ “Social and Personal,” Milwaukee Journal, October 4, 1897, p. 2; “A Building with Nine Lives,” Milwaukee Journal, January 13, 1955, p. 24.

- ^ “Milwaukee Women Take to the Water,” Milwaukee Journal, June 27, 1902, p. 7.

- ^ “A Building with Nine Lives,” Milwaukee Journal, January 13, 1955, p. 24.

- ^ “Basketball Not for Girls,” Milwaukee Sentinel, March 17, 1901, Children in Urban America Project website, accessed October 26, 2014.

- ^ “Women as Members of Athletic Club,” Milwaukee Journal, July 26, 1918, p. 11.

- ^ Oliver Kuechle, “Milwaukee Athletic Club’s Early History Filled with Triumphs Which Won It National Renown,” Milwaukee Journal, February 18, 1940, section 3, p. 3.

- ^ Doug Schmidt, They Came to Bowl: How Milwaukee Became American’s Tenpin Capital (Madison, WI: Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 2007), 8-9.

- ^ Wright’s Milwaukee City Directory (Milwaukee: Wright’s Directory Company, 1927), 2691.

- ^ Schmidt, They Came to Bowl, 9.

- ^ Schmidt, They Came to Bowl, 114.

- ^ Castle Ice Gardens advertisement, Milwaukee Journal, June 18th 1922. https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1499&dat=19220618&id=Z6xRAAAAIBAJ&sjid=WSEEAAAAIBAJ&pg=4376,2967323&hl=en.

- ^ “What About Indoor Rink?” Milwaukee Journal, March 6, 1927, Sports, p. 2.

- ^ “Fire Wrecks Roller Rink,” Milwaukee Sentinel, October 29, 1929, p. 1.

- ^ Charlie House, “Closing of Local Rink Recalls the Heyday of Roller Skating,” Milwaukee Journal Green Sheet, May 6, 1966, p. 1.

- ^ “1979 Annual Activities Report, Recreation Division,” Milwaukee County Parks Commission, 1979, p. 21.

- ^ “Annual Report of Recreation Department,” Milwaukee County Parks Commission, 1946, p. 18.

- ^ “Annual Report of Recreation Department,” Milwaukee County Parks Commission, 1951, p. 6.

- ^ “Annual Report of Recreation Department,” Milwaukee County Parks Commission, 1952, p. 18, 24.

- ^ “Boys and Girls Club of Greater Milwaukee,” Milwaukee County Historical Society website, accessed April 10, 2015; “Boys & Girls Club Provides Haven from Boredom, Streets,” Milwaukee Sentinel, July 20, 1993, p. 1.

- ^ “Milwaukee,” Milwaukee Journal, April 17, 1948, p. 1.

- ^ “Another City Bathtub to Go,” Milwaukee Journal, January 10, 1963, p. 1.

- ^ “Public Natatorium Restaurant,” Old Milwaukee website, posted September 20, 2011, accessed October 30, 2014; Larry Sandler, “Panel Backs Keeping 3 Pools,” Milwaukee Sentinel, October 24, 1989, Local News, p. 1.

- ^ “Panel Backs Keeping 3 Pools.”

- ^ “Milwaukee,” Milwaukee Journal, July 20, 1954, p. 1.

- ^ “Indoor Skating Rink Opens New Ice Age,” Milwaukee Journal, January 25, 1970, p. 18.

- ^ “Mayfair Project Announced,” Milwaukee Sentinel, November 18, 1977, Business News, p. 1.

- ^ Mike Nichols, “Beloved Ice Rink Was Frozen Out of Mayfair,” Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel, October 18, 2005, Waukesha Section, p. 1.

- ^ Bill Milkowski, “Skating Fever Spreading across US,” Milwaukee Journal Accent, April 20, 1979, p. 1.

- ^ Thomas Collins, “Skate Kings, Queens Frolic at the Palace,” Milwaukee Sentinel, December 20, 1982, p. 5.

- ^ Patricia Roberts, “Club Serves Up Indoor Tennis in Brookfield,” Milwaukee Journal, December 16, 1965, p. 14.

- ^ Schmidt, They Came to Bowl, 30, 32.

- ^ “Sound Body,” Milwaukee Turners webpage, accessed November 2, 2014.

- ^ “Oldest Bowling Alley in America Turns 100,” Fox News website, posted September 15, 2008, accessed November 7, 2014.

- ^ “About Us,” Pettit National Ice Center webpage, accessed November 2, 2014.

- ^ “Sports Facilities,” Milwaukee County Parks webpage, accessed October 21, 2014.

- ^ Stacy Vogel Davis, “No More Susan Sarandon?” Milwaukee Business Journal website, posted February 5, 2014, accessed November 2, 2014.

- ^ “Main Page,” Brookfield Indoor Soccer Complex website, http://www.brookfieldindoor.com/index.aspx, accessed November 1, 2014.

- ^ “Main Page,” Paintball Dave’s Website, http://www.paintballdaves.com/newhomepage125.htm, updated October 3, 2013, accessed November 6, 2014.

For Further Reading

Clark, James I. 100 Years of Service to Youth: A History of the Young Men’s Christian Association of Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Milwaukee: The Association, 1958.

Ogden, Marion G, “Amusement and Recreation in Milwaukee: Municipal Recreation, A Bulletin of the City Club, 1914.” Milwaukee: City Club of Milwaukee, 1914.Schmidt, Doug, They Came to Bowl: How Milwaukee Became American’s Tenpin Capital, Madison: Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 2007.

Wiltse, Jeff, Contested Waters: A Social History of Swimming Pools in America, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.