Now dominated by the Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra, Milwaukee’s music performance scene grew out of a diverse array of amateur programs rooted in the city’s immigrant heritage. In the mid-twentieth century, some musical groups professionalized, with leading musicians shaping the artistic direction and making Milwaukee home to nationally important music. But space remains for amateur performers as well as a wide range of genres.

The Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra

The Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra (MSO) has stood at the center of Milwaukee’s concert music scene since 1969. That year, the orchestra became fully professional, expanded to 84 players, and moved into the new Uihlein Hall of the Milwaukee County Performing Arts Center (now the Marcus Center for the Performing Arts). At last, it appeared as a viable local alternative to the long-standing Chicago Symphony series in Milwaukee, which finally ended in 1986.[1]

MSO[2] was conceived amid the frustration of competing efforts, going back to 1890, among Milwaukee’s German, Italian, and Polish communities to establish an orchestra. The Milwaukee Pops Orchestra, which was organized in 1949, became the Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra a decade later.[3] In 1960, the MSO board brushed aside the locals’ favorite-son conductors and hired an outsider, Harry John Brown, as music director.

The orchestra bobbed through artistic crests and troughs over the years, as it rose from a semi-professional pops outfit to a professional ensemble devoted to the high-art Western tradition. The budget has grown from $210,000 in 1961 to nearly $18 million in 2013, but financial distress has been nearly constant.[4] Beginning in 2003, the players made salary concessions on nearly every contract, and the MSO ran severe deficits. The 2013 contract reduced the number of permanent authorized positions and was touted as a long-term, live-within-means fix to chronic problems.

Despite the chronic financial distress, music directors Brown and Kenneth Schermerhorn (1968-1980) focused on building the orchestra in the 1960s and 1970s. Schermerhorn led the MSO’s wildly successful first trip to Carnegie Hall. Composer-conductor Lukas Foss (1981-86), a big name who never lived in Milwaukee, could be brilliant and disappointing on the same program. Zdenek Macal (1986-1993), a blazing success in his early years in Milwaukee, appeared to lose interest in the orchestra and alienated himself from his musicians and management as he focused on finding his next position.

The orchestra drifted during Macal’s last years. It hit its low point, artistically, following Macal’s departure. With no leader on site, concerts sagged under a parade of guest conductors. Low morale, due partly to lack of podium leadership and partly to ongoing contract disputes between the players and management, took a toll. Performances were never terrible but often fell into dull routine in those years.

In 1994, the appointment of Frank Almond, an accomplished and dedicated young violinist just out of Juilliard, marked the beginning of the MSO’s artistic turnaround. He led by example as he brought a new level of skill and sonic beauty to the orchestra’s first chair and played with total commitment regardless of the occasion. After Almond, generational turnover among the orchestra’s first-chair players brought a new era of energy and attitude to the orchestra: Principal clarinetist Todd Levy, principal trumpeter Mark Niehaus, principal horn player William Barnewitz, principal bassist Zachary Cohen, and others played important roles in making the Milwaukee Symphony a cohesive, spirited unit.

Steven Ovitsky’s entrance as executive director, in 1995, also helped to change attitudes of the rank and file. Ovitsky brought orchestra players to sit on every important board committee—a radical practice at the time. Musicians now were in on all management and board business, contributing to financial decisions and analysis and marketing practices. Management and musicians became allies in the preservation of the orchestra.

Andreas Delfs, a young German conductor and former Juilliard classmate of Almond, became music director in 1997. He largely oversaw the generational turnover in the orchestra and eagerly became the public face of the orchestra.[5] Delfs took an interest in board matters and fundraising even as he guided the orchestra to higher and higher artistic levels during his 12-year tenure.

Edo de Waart succeeded Delf in 2009. An internationally known, A-list conductor, de Waart was living in Middleton, Wisconsin, for personal family reasons and commuting to Hong Kong when MSO management successfully approached him about the position. Under de Waart’s leadership, the Milwaukee Symphony came to be the center of Western art music in Milwaukee. But classical music—or even orchestral music—does not begin and end with the MSO.

The Wisconsin Philharmonic is also worthy of note.[6] The orchestra began as the Waukesha Symphony in 1947, on the campus of Carroll College. It was truly a community orchestra, open to amateur players. A community of music teachers sprang up around the participants’ enthusiasm for their orchestra. But its mission blurred over the years, as the orchestra became independent of the college and sought donors and an audience. By the 1990s, it had become a sleepy institution with both amateur and professional musicians and with no clear reason for existing. The board hired Alexander Platt as music director in 1997. He began to professionalize the orchestra, which now enjoys a mix of amateur and professional players who perform energetically and attentively for Platt, whom critics generally applauded.

Classical Music in Nineteenth and Early Twentieth-Century Milwaukee

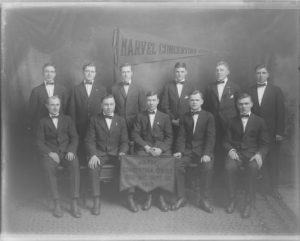

The large numbers of Germans arriving in Milwaukee in the 1840s brought German high culture, notably music, with them.[7] For a time, the town’s nickname was “Deutsche Athen”—German Athens. They formed groups such as the Milwaukee Musical Society (MMS), which organized in 1849 as the Musikverein and staged all manner of concerts, recitals, and even operas. By 1899 MMS had presented 386 concerts,[8] some by locals and some by big-name guests artists. Many of these events took place in the Pabst Theater,[9] built in 1895 after the Das Neue Deutsche Stadt-Theater (New German City Theater) burned down.[10]

Milwaukee’s German musicians networked extensively with similar musical communities around the country. In 1886, MMS hosted a national Saengerfest (Singers Festival) that drew eighty-five singing groups from St. Louis, New York, Chicago, Louisville, Cincinnati, and other cities.[11]

Milwaukee-born Eugen Luening (1852-1944), a Milwaukee native who had studied conducting in Germany with Richard Wagner, led the MMS and later became head of the University of Wisconsin-Madison music department. Luening also founded one of the several musical colleges that eventually merged into the current Wisconsin Conservatory of Music, today the home of several chamber groups and an important center of private, pre-college music education.

Milwaukee’s 19th-century musical life centered largely on participatory amateur groups, bands, and especially choruses. Many existed in the German community; five German-language choruses, including the Milwaukee Liedertafel,[12] persisted into the 21st century, though with much-diminished influence and audience.

The choral tradition remains strong in Milwaukee. The superb Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra Chorus,[13] led by professional choir masters, graces many MSO concerts and puts on its own well-attended concerts. Margaret Hawkins founded the MSO Chorus in 1976, to supplant the then-faltering Bel Canto Chorus. The Bel Canto, founded in 1931,[14] has since rebounded under the sustained creative leadership of Richard Hynson.

Milwaukee’s Germans and Italians for decades vied for musical supremacy. Through the middle of the 20th century, conductor and musical entrepreneur John-David Anello (1907-1990) was the Italians’ champion. He founded the Italian Opera Chorus in 1933, led the Italians’ effort to get a symphony orchestra off the ground, and was the first leader of the Milwaukee Pops, which eventually evolved into the MSO. Anello became Milwaukee’s Kapellmeister. He won Milwaukee County contracts to run the enormously popular Music Under the Stars[15] programs at the Washington Park Pavilion for 40 years, and he presided over music at the massive Milwaukee Centennial Celebration in 1946.

The Italian Opera Chorus was renamed the Florentine Opera Chorus in 1942. This highly successful 100-voice chorus staged its first full opera production in 1950. It soon evolved into the Florentine Opera Company, which after 2005, under leadership of William Florescu,[16] became an important presenter of new works and innovative stagings of old ones.

Though Anello is undeniably a key figure in Milwaukee’s musical history, his influence faded as he aged. The Milwaukee Symphony chose Harry John Brown over Anello as music director. A rapidly professionalizing music scene generally restricted his opportunities through the 1960s and 1970s. Even the Florentine moved on from Anello as it grew into a typical American regional production company, with the Milwaukee Symphony in the pit, its stage at Uihlein Hall and guest stars fronting a local chorus.

A number of modest opera efforts popped up in the mid-century, among them Clair Richardson’s Skylight Opera. Richardson, a public relations man by trade and a tireless fund-raiser for cultural causes, was the Milwaukee Pops’ business manager for three years.[17] Richardson and a circle of friends conceived the Skylight as an intimate musical-theatrical experience and resolved to present all their operas and operettas in English.[18] The first Skylight performance venue was a ninety-seat affair on Jackson Street. When wrecking balls threatened that building in 1962, he moved on to a converted garage on Jefferson Street facing Cathedral Square. Over the years there, the Skylight established itself as a quirky but essential piece of Milwaukee culture.

After Richardson died in 1980, Colin Cabot, scion of a wealthy Eastern family and in Milwaukee via marriage, took over. Cabot took on the task of modernizing and professionalizing the company, first by bringing in Francesca Zambello[19] and Stephen Wadsworth[20] as co-artistic directors. Both have become major figures in the opera world. In their few years in Milwaukee, they transformed the Skylight.

Cabot immediately began scouting for new locations for the company. He spotted an old warehouse in the Third Ward, partly occupied by the shoestring Theater X company. Cabot envisioned taking over the six-story building and the lot next door and combining them in a theater complex. Generous donations from Cabot, his family, and local supporters of the Skylight made the Broadway Theatre Center a reality in 1993. Its 358-seat main stage, modeled after French court theaters and whimsically decorated with theatrical trompe-l’oiel, is the most charming and intimate theatrical space in Milwaukee.

Now known as the Skylight Music Theatre, the company, like every other Milwaukee musical institution, has suffered through crisis and controversy. The most bitter and notorious came in the summer of 2009,[21] with an attempt to fire beloved artistic director Bill Theisen. But it has put on consistently good shows and has a daring artistic director, Viswa Subbaraman,[22] to take it in new directions.

We must note one other opera company, the Milwaukee Opera Theatre (MOT) run by Jill Anna Ponasik.[23] A singer trained at Rice University and the University of Minnesota, Ponasik returned to her hometown Milwaukee in 2008 when her husband, a research physician, joined the Medical College of Wisconsin. Her former voice teacher, Pat Crump, was the nominal head of Milwaukee Opera Theatre, a legal entity that had been dormant for many years. She wondered whether Ponasik might do something with it.

Ponasik promptly made MOT the hippest highbrow thing in town, with wildly daring and vastly entertaining new shows and sly recasting of old ones. The most pleasantly notorious is Fortuna the Time-Bender vs. The Schoolgirls of Doom, a hilarious comic-book opera by Jason Powell.[24]

Chamber Music

The Fine Arts Quartet dominated chamber music in Milwaukee for decades. The group, established in Chicago in 1946, built a national following by playing on ABC Radio’s Sunday morning broadcasts from 1946 to 1954. The quartet, led by first violinist Leonard Sorkin, appeared on the Ed Sullivan Show and the Today show, toured Europe annually, and recorded extensively.

In 1963, after several seasons of summer concerts at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee (UWM), the Fine Arts accepted the school’s invitation to become quartet in residence and full professors of music. Sorkin retired from the quartet in 1982; cellist George Sopkin retired in 1979 and violist Bernard Zaslav retired in 1980; and second violinist Abram Loft in 1979. By 1983, violinists Ralph Evans and Efim Boico, violist Jerry Horner, and cellist Wolfgang Laufer formed a new Fine Arts partnership that persisted for decades. UWM ended its relationship with the Fine Arts Quartet in 2018.[25]

Todd Levy, the MSO’s principal clarinetist, also taught as an adjunct faculty member at UWM. He further engaged with the school through the Chamber Music Milwaukee series. Levy and faculty members Gregory Flint, Elena Abend, and Jonathan Monhardt oversee the series, which brings together music department and MSO personnel in mixed chamber music, much of it intriguing and rarely heard. In addition to the series, the university presents dozens of faculty and guest recitals each year. The very strong guitar program, led by Rene Izqueirdo (classical) and John Stropes (American finger-style), is especially active. Faculty programs and recitals by top-notch touring professionals abound.

Frank Almond, the MSO’s concertmaster, started his Frankly Music Series in 2003. Almond, a charming and witty speaker, typically opens with a little talk about the music on the evening’s program. He usually blends players from the MSO with friends and colleagues through his New York and international connections. Pianists William Wolfram, Adam Golka, and Christopher Taylor are frequent guests. Cellist Lynn Harrell has also graced his series, along with violists Nicholas Cords and Toby Appel. Almond split his first nine seasons between the intimate hall at the Wisconsin Conservatory of Music and the larger Schwann Hall at Wisconsin Lutheran College. Starting in 2014-2015, the smaller events took place at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church.

The Wisconsin Conservatory also remains an important chamber music venue. The Conservatory is the home of the Prometheus Trio and the Philomusica Quartet. Pianist Stefanie Jacob and cellist Scott Tisdel, husband and wife, are the core of the Prometheus; Timothy Klabunde, a Milwaukee Symphony colleague of Tisdel, has been their violinist since 2005. Another husband and wife team, Alexander Mandl and Jeanyi Kim, take turns in the first violin chair of the Philomusica Quartet; they play with violist Nathan Hackett and cellist Adrien Zitoun.

Zitoun, Hackett, and Kim are members of the MSO. Several young players in the orchestra have been ambitious with chamber music. Cellist Peter Thomas has played the full Beethoven cycle with pianist Matthew Bergey. He is also a member of the Arcas Quartet[26] with the MSO’s Ilana Setapen and Margot Schwartz (violins) and Wei-Ting Kuo.

New Music

Although much music performance in Milwaukee focuses on the past, some venues also present more recent compositions. The UWM music department, a full-service unit on the conservatory model, puts on many student composer concerts. Yehuda Yannay’s Music from Almost Yesterday has for decades brought new music from living composers around the world to Milwaukee. Christopher Burns’ Unruly Music series, given twice a year in festival format, live out on the edge of the cutting edge.

But New Music in Milwaukee means Present Music. Kevin Stalheim, a trumpet player by trade, had just finished a graduate conducting degree at UWM in 1982 when he decided to start a new group in Milwaukee. He started putting on concerts financed by his personal credit cards. He soon narrowed the focus to new music in general and to commissioning composers in particular.

Stalheim’s business model turned on maintaining a flexible ensemble, from three to forty players as needed, who embraced the idea of new music (which not all classically trained players do). Within a few years, he had a core group that could quickly make sense out of graphic notations and handle extended techniques, offering not just technical accuracy but skilled interpretation.

Unlike most new-music directors, Stalheim made concerts into shows. Many of Present Music’s programs are like happenings. Ping-pong balls rain down from balconies through black light. Dozens of belly dancers emerge from nowhere. That sort of thing, the brilliant musicianship and Stalheim’s utterly unpredictable programming, won over a substantial and adventurous audience. They do not come to re-enjoy the familiar. They come to find out what Stalheim has cooked up this time.

Stalheim has cultivated relationships with established and emerging composers alike. Present Music has commissioned John Adams, Michael Torke, Michael Daugherty, Jerome Kitzke and premiered dozens of works by Kamran Ince. Stalheim has introduced many remarkable composer-performers to Milwaukee, notably Amy X Neuburg and Caroline Shaw. The annual Present Music Thanksgiving Concert at the Cathedral of St. John the Evangelist—almost always sold out—has become a holiday staple in Milwaukee.

Footnotes [+]

- ^ “Chicago Symphony’s Faithful Look Back on a Golden Age,” Milwaukee Sentinel, May 30, 1986, https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1368&dat=19860530&id=XQckAAAAIBAJ&sjid=hhIEAAAAIBAJ&pg=2529,325755&hl=en, last accessed 2015.

- ^ “Many Fits and Starts for Early Symphonies,” Milwaukee Journal, September 4, 1983, https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1499&dat=19830904&id=hm8aAAAAIBAJ&sjid=_CkEAAAAIBAJ&pg=6307,1991037&hl=en, last accessed 2015.

- ^ “A Brief History of the MSO,” last accessed September 1, 2017.

- ^ Tom Strini, “Milwaukee Symphony in Crisis—Again,” Tom Strini Writes blog, October 16, 2013, last accessed September 1, 2017.

- ^ Jim Higgins, “Trumpeter Niehaus Named Milwaukee Symphony’s President,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel September 12, 2012, last accessed September 1, 2017.

- ^ “About the Wisconsin Philharmonic,” Wisconsin Philharmonic website, last accessed September 9, 2015.

- ^ “A Brief History of…Music in Wisconsin,” The Wisconsin Mosaic, last accessed September 1, 2017.

- ^ Jon Teaford, Cities of the Heartland: The Rise and Fall of the Industrial Midwest (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1994), 88, last accessed September 1, 2017.

- ^ Jim Rankin, “The Pabst Theater—A Paragon of Playhouses,” Astor Theater website, last accessed September 1, 2017.

- ^ “History of the Pabst Theater,” The Pabst Theater Group website, accessed September 2015.

- ^ “Singing Societies and the 1886 Saengerfest,” German American Music: Wisconsin’s Tradition, Center for the Study of Upper Midwestern Cultures website, last accessed September 1, 2017.

- ^ Erin Richards, “Voice of German Choruses Lingers,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, November 28, 2010. http://www.jsonline.com/news/milwaukee/110950234.html, accessed September 2015.

- ^ “Chorus,” Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra website, last accessed September 1, 2017.

- ^ “Bel Canto Chorus,” Wikipedia, last accessed September 10, 2015.

- ^ Historic Milwaukee, Pictures from Milwaukee’s Past, http://historicmke.tumblr.com/post/41627513411/the-milwaukee-county-park-commissions-music, accessed September 2015.

- ^ Tom Strini, “Those Florentine Opera ‘Elmer Gantry’ Grammy Awards,” Urban Milwaukee, February 21, 2012, last accessed September 1, 2017.

- ^ “Clair Richardson Dies during Surgery; Founded Skylight Theater,” Milwaukee Sentinel, September 13, 1980. https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1368&dat=19800913&id=TYBQAAAAIBAJ&sjid=ABIEAAAAIBAJ&pg=2940,2324952&hl=en

- ^ Colin Cabot, “The Thirty Years War? A Brief and Subjective History of the Skylight,” Skylight Music Theatre website, last accessed September 1, 2017

- ^ Francesca Zambello website, last accessed September 1, 2017.

- ^ “Faculty Profile: Stephen Wadsworth,” The Julliard Journal, http://www.juilliard.edu/journal/stephen-wadsworth?destination=node/13216, last accessed September 2015.

- ^ Tom Strini, “Skylight’s Future Might Depend on the Guy It Dumped,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, June 29, 2009, last accessed September 1, 2017.

- ^ Tom Strini, “The Skylight’s New Artistic Director,” Urban Milwaukee, September 6, 2012, last accessed September 1, 2017.

- ^ Jill Anna Ponaski website, last accessed September 1, 2017.

- ^ Tom Strini, “Milwaukee Opera Theatre: Comic (Book) Opera,” Tom Strini Writes, May 9, 2014, last accessed September 1, 2017.

- ^ Bill Glauber, “Fine Arts Quartet Marks 55th and Final Season at UWM and Vows to Play On,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, January 22, 2018, accessed January 26, 2018.

- ^ Arcas Quartet Facebook page, https://www.facebook.com/Arcas-Quartet-139328242787339/timeline/, accessed September 2015.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.