“Wi-saka” does not adorn the gate of any park, or the entrance to a school. However, the Potawatomi people who inhabited Waukesha and surrounding areas before European arrival know the name well. Potawatomi oral tradition calls Wi-saka “the Great Spirit” and credits him with the creation of the world. The naming of modern-day Waukesha, though, belonged to Europeans. “Blair,” “Randall,” “Bethesda,” “Barstow,” “Dunbar”—the names of schools, parks, and streets—are also the last names of the first white settlers, who developed the first businesses in the city (iron works, mills) or were firsts in other ways. But Waukesha’s history has deeper roots, other firsts whose names may not inhabit any street but who made up the heritage of Prairieville, now the City of Waukesha.

Native Settlement

The name that appears most often in Native American history of Waukesha is Potawatomi.[1] The Potawatomi, part of the Anishinaabe, are the Keepers of the Sacred Fire. They grew corn, beans, squash and other crops in the summer months and migrated to warmer climates during the harsh Wisconsin winters. They were also fishers and hunters who settled close to rivers and streams, including the Pishtaka (the Fox River) and many other waterways. White settlers described them as peaceful and friendly, while pointing out that when white men arrived, southern Wisconsin “had lately been cleared of hostile Indians.”[2]

Arrival of White Americans

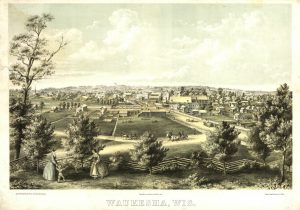

Four Euro-American men from New England arrived by horseback to settle the banks of the Pishtaka in 1834: brothers Morris D. and Alonzo Cutler, John Mandeville, and William Luther.[3] They cleared land between what later became Waukesha High School (currently Les Paul Middle School) and the Fox River.[4] The first white family group to move to Waukesha was that of B.S. McMillan; the McMillans built a cabin where St. Joseph’s Catholic Church and the Waukesha County Museum now stand. Travel between Milwaukee and Prairieville turned McMillan’s cabin into the future city’s first hotel. By 1836, a settlement of more than two dozen cabins stretched out along the Fox River, a road was built to Milwaukee, and a private school had opened in the house of Nathaniel Walton. A permanent schoolhouse was built soon after. By 1838, the settlement had 150 inhabitants, as well as its first church (First Congregational Society) in the house of Robert Love.

The area that became Waukesha County was originally included within Milwaukee County. What is now the city of Waukesha was identified in the late 1830s as Prairie Village[5]; the settlement soon was renamed Prairieville. The surrounding Town of Prairieville was created in 1842, with the first town meeting held on April 5. Among those in the meeting were two future Wisconsin governors, William A. Barstow and A.W. Randall.[6] In 1846, the Village of Prairieville was incorporated from a portion of the land in the Town, changing its name to Waukesha in 1847.[7] Also in 1846, the village became the seat of Waukesha County, edging out Delafield, Genesee, Pewaukee, and Muskego for the position.[8] The village became the City of Waukesha in 1896. By 1900, the municipality had 7,419 residents.[9]

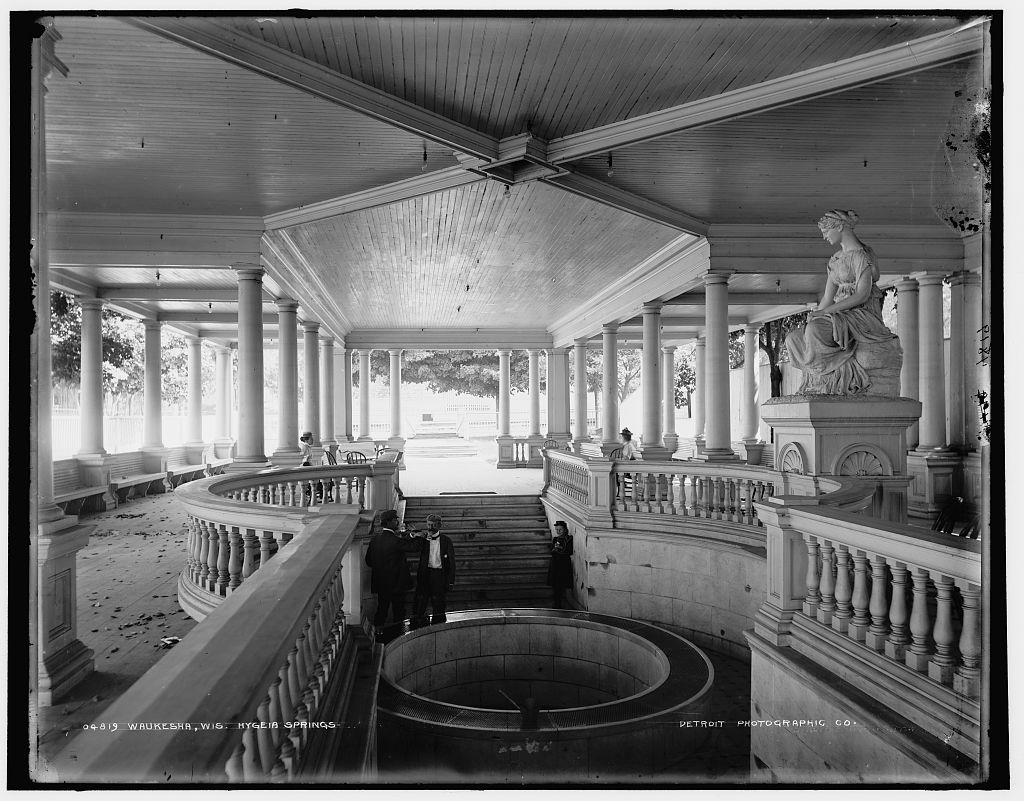

Waukesha Water

Waukesha’s springs gained the municipality a national reputation in the nineteenth century. A newspaper article from 1869[10] pinned the discovery of the medicinal properties of the spring on Colonel Richard Dunbar, a dying and diabetic New Yorker who visited Waukesha in August 1868.[11] The news of his miracle cure after drinking “a half dozen dipper fulls” attracted legions of tourists to Waukesha.[12]

The spring city era lasted until 1918, but the city continued boasting of its rich water history, even after thirsty foundries moved into the area and the water supply became a problem. Factories needed water, and to meet the demand the city drilled new wells—some nearly 2,000 feet deep—into the sandstone aquifer.[13] Farmers sold their land just outside city borders and developers built new subdivisions. The city annexed and grew. City officials were not worried about water; in fact, waste was encouraged, as the more water customers used, the lower the rate they would pay.[14] Then came 1987, when Waukesha’s water became a problem. High levels of radium alarmed the public as years of overpumping had lowered the water table hundreds of feet.[15] Radium-contaminated aquifers provided about 85 percent of the drinking water for the city. Waukesha resisted the State of Wisconsin’s order to fix its radium problem and even sued the Environmental Protection Agency for overreaching.[16] Eventually, the city turned to Lake Michigan as a potential source of clean water. After years of complex international negotiations, in 2017 Waukesha secured a forty-year agreement to buy Lake Michigan water from Milwaukee and return water through Racine.[17]

Demographics

The Joseph Melendes and Antonia Don Diego Melendes family arrived in Waukesha in 1919 and built their home on The Strand, an area European immigrants had first settled. Like the McMillan home in the nineteenth century, the Melendes home became a sort of hotel for Mexican immigrants arriving in the city. A strong tradition of seasonal migration between Texas and Waukesha supported the Waukesha area’s agricultural enterprises. United Migrant Opportunity Services located its original headquarters in Waukesha but moved to Milwaukee in 1968.[18] Since then, attracted by a strong manufacturing industry, thousands of other families with Latinx surnames have continued to make Waukesha their home. As of 2016, the US Census Bureau estimated that 12.5 percent of the city’s 72,489 inhabitants were Hispanic or Latino.[19]

A hotbed of Republicanism since the nineteenth century, the city was home to The Waukesha American Freeman, an abolitionist newspaper that in 1848 denounced the state new constitution because it denied voting rights to blacks. The Waukesha Freeman, its successor newspaper founded in 1859, continues to serve the city in the twenty-first century. In the twenty-first century, the city still has less than 4 percent African American residents. The Native American population is .1 percent, despite the city’s history as the home of Native tribes. Asian Americans make up 3.7 percent of the population.[20]

Economy

Waukesha cites its parks and schools as economic strengths, and the diversity of its population as both a strength and a challenge. Since its foundation, Waukesha has been one of the most prosperous communities in Wisconsin, boasting a complex system of mills and iron work factories in the nineteenth century.

More than half of the City of Waukesha houses, 58.6 percent, are owner occupied.[21] Median household income for 2013-2017 was $61,380, with 10.6 percent of the population living in poverty.[22]

Footnotes [+]

- ^ Spelled “Pottawomie” in early Waukesha documents.

- ^ Theron W. Haight, ed., Memoirs of Waukesha County (Madison, WI: Western Historical Association, 1907), 21-22.

- ^ Haight, Memoirs of Waukesha County, 22.

- ^ Haight, Memoirs of Waukesha County, 21 and 25.

- ^ Haight, Memoirs of Waukesha County, 26, gives the founding date as either 1835 or 1836; Western Historical Co., History of Waukesha County [Bicentennial ed.] ([Waukesha, WI: Waukesha County Historical Society], 1976; originally published, 1880), accessed through Hathitrust Digital Library, 793, gives the founding year as 1839.

- ^ Western Historical Co., History of Waukesha County [Bicentennial ed. ([Waukesha, WI: Waukesha County Historical Society], 1976; originally published, 1880), accessed through Hathitrust Digital Library, 36.

- ^ An Act to Amend an Act Entitled “An Act to Incorporate the Village of Prairieville, and for other purposes,” February 1847, Internet Archive.

- ^ Haight, Memoirs of Waukesha County, 83.

- ^ Wisconsin [1940 US Decennial Census, Population, Volume 1], 1163, last accessed March 8, 2019.

- ^ “Medical Springs in Wisconsin” Evening Wisconsin, April 1869, p. 2, Box 22, Folder 13, Increase A. Lapham Papers, 1825-1930, Wisconsin Historical Society.

- ^ The Dunbar Oak, Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, https://dnr.wi.gov/topic/ForestManagement/…/documents/012-DunbarOak.pdf, now available at https://dnr.wi.gov/topic/forestmanagement/everyrootananchor/documents/012-DunbarOak.pdf, last accessed March 19, 2019.

- ^ “Medical Springs in Wisconsin.”

- ^ Sarah Gardner, “Waukesha: A Spa Town That Took Its Water for Granted,” Marketplace, February 3, 2015, last accessed March 13, 2019.

- ^ Gardner, “Waukesha,” last accessed March 13, 2019.

- ^ Gardner, “Waukesha,” last accessed March 13, 2019.

- ^ Gardner, “Waukesha,” last accessed March 13, 2019.

- ^ Jim Riccioli, “How We Got Here. Waukesha’s Journey to Get Water from Milwaukee Almost Over,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, October 31, 2017; Don Behm, “Waukesha Common Council Approves 40-Year Agreement to Buy Lake Michigan Water from Milwaukee,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, December 5, 2017, last accessed March 13, 2019.

- ^ Marc Simon Rodriguez, The Tejano Diaspora: Mexican Americanism and Ethnic Politics in Texas and Wisconsin (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2011), 112.

- ^ QuickFacts, Waukesha City, Wisconsin, United States Census Bureau website, last accessed March 8, 2019.

- ^ Waukesha Population Statistics, Neighborhood Scout website, last accessed March 13, 2019.

- ^ QuickFacts, Waukesha City, Wisconsin, United States Census Bureau website, last accessed March 8, 2019.

- ^ QuickFacts, Waukesha City, Wisconsin, United States Census Bureau website, last accessed March 8, 2019.

For Further Reading

Education for a Lifetime: A History of the First 75 Years of Waukesha County Technical College, 1923-1998. Pewaukee, WI: Waukesha County Technical College, 1998.

Haight, Theron W., ed. Memoirs of Waukesha County. Madison, WI: Western Historical Association, 1907.

Langill, Ellen. Carroll College, The First Century 1846-1946. Waukesha, WI: Carroll College Press, 1980.

Langill, Ellen D. “History of Education in Waukesha County.” In From Farmlands to Freeways, A History of Waukesha County, Wisconsin, edited by Ellen Langill and Jean Penn Loerke, 275-327. Waukesha, WI: Waukesha County Historical Society, 1984.

The History of Waukesha County, Wisconsin. Chicago, IL: Western Historical Company, 1880.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.