Native Americans, as the first inhabitants of the Greater Milwaukee area, were the first to use the lakes, rivers, and streams that dominate the landscape as a means of transportation. In Milwaukee in particular, they used the three connecting rivers and lakeshore as major thoroughfares for canoe travel and harvesting water-based food. Native peoples of the Great Lakes region used both birchbark and dugout canoes for water travel. Dugout canoes, made from hollowed-out logs, were heavier than their birchbark counterparts and were generally preferred for travel in large bodies of water where they would not need to be portaged. Birchbark canoes, made of ribbed wood frames and covered in pitch-sealed tree bark, were favored for their light weight and maneuverability. Birchbark canoes, powered by a rower with cedar paddles, could readily transport small groups of individuals to favored fishing spots on the Milwaukee River, through the miles of wild rice in the Menomonee Valley, and south to villages along the Kinnickinnic.[1]

In the late seventeenth century, French explorers arrived in the region on a new type of water vessel, the sailing ship. The first European vessel to sail Lake Michigan was the French ship Le Griffon. Although it sank at an unknown location within a few months of its launch from the east end of Lake Erie, its presence was an early indication of the coming dominance of sailing ships on the Great Lakes. Despite the presence of sailing vessels in the region in the seventeenth century, canoes continued to be the preferred method for water travel around the Milwaukee area into the nineteenth century. In the 1670s, when Father Jacques Marquette and Louis Joliet embarked on their circle route from St. Ignace down the Mississippi River and back up Lake Michigan with a pit stop at what is now Milwaukee, they did so in canoes. The waterway circuit they travelled served as the chief highway for international commerce over the next two centuries of fur trading.[2]

In the early nineteenth century, developments in water transportation in the eastern United States spurred migration into the western Great Lakes and facilitated the growth of the Milwaukee area. Solomon Juneau was just moving into his trading post at Water Street and Wisconsin Avenue when the Erie Canal was completed in 1825. In the following decades, horse-drawn canal boats filled with Yankee-Yorkers packed the 363-mile waterway headed westward. At the entrance to Lake Michigan at the Straits of Mackinac, passengers boarded three-masted schooners and side-wheel steamers headed south toward the ports dotting the coast in a quest for regional dominance. Milwaukee was one of those emerging ports. Despite Milwaukee’s natural harbor, landing a ship proved to be a dangerous task. The first ship to succeed was the steamer Michigan, which arrived in 1835, before Milwaukee had a permanent pier for docking.

The lack of maritime infrastructure needed for a port city did not dissuade Byron Kilbourn, who joined the period’s “canal mania.” Inspired by the success of the Erie Canal and his experience in canal construction in Ohio, Kilbourn secured a charter for the Milwaukee and Rock River Canal in 1838. With grandiose plans to construct a direct waterway connection from Kilbourntown to the Rock River in Fort Atkinson via the lakes of Waukesha County, Kilbourn moved forward quickly by hiring a young surveyor and engineer from New York named Increase Lapham. After completing only just over a mile of canal ditch and a crude dam at North Avenue, Kilbourn abandoned the project by 1842.[3]

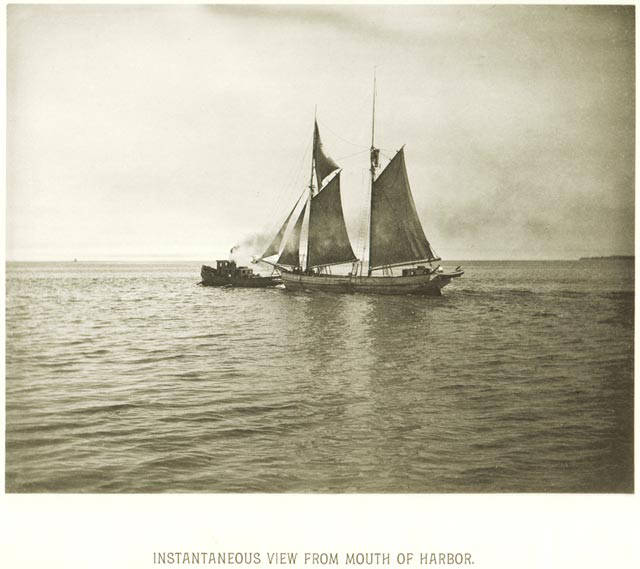

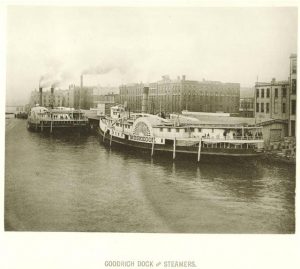

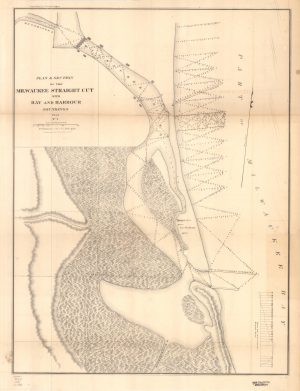

Despite the failed canal project, Milwaukee was still poised to profit from water commerce. The first improvements to Milwaukee’s harbor came in the early 1840s when cargo and passenger docks were built into the lake at the edge of what is now Clybourn Street. With the completion of the “straight-cut” through the Jones Island peninsula in 1857, Milwaukee had infrastructure to consider itself a port city. Schooners and steamers could now dock in the harbor or access the newly constructed warehouses on the edges of the Milwaukee River. While steamers became favored for passenger travel, schooners remained the preferred method for cargo transport. Improved maritime infrastructure facilitated an economy based significantly on water transportation. On the expanding frontier of southeastern Wisconsin in the nineteenth century, wheat had quickly become the chief crop. Milwaukee produced a significant amount of grain, but more money could be made shipping wheat from points west than from growing it locally. This lucrative business made fortunes for some Milwaukeeans, and it also significantly altered the city’s visual appearance. Alexander Mitchell, one Milwaukee’s first banking barons, turned the near-defunct Milwaukee and St. Paul Railway company into a railroad empire thanks to the profitability of grain distribution. The lucrative market for shipping grain by schooner was also a major motivation in the funding of the “straight-cut” and the construction of grain elevators along the Milwaukee River.[4]

The island that was created by the dredging of the “straight-cut” also became home to a short-lived ship construction yard operated by James M. Jones. The financial panic of 1857 followed by a destructive storm destroyed his operation, but ship construction continued in Milwaukee. The Wolf & Davidson shipyards were the largest in the city in the latter half of the nineteenth century, contributing significantly to the more than 2,500 vessels that plied the Great Lakes. In his environmental history of Milwaukee, John Gurda explained that Milwaukee’s harbor saw a considerable amount of that lake traffic, “averaging more ships per day in the 1870s than average daily aircrafts were recorded passing through Milwaukee Mitchell International Airport in 2016.” Given the number of vessels traversing the lake at the time, it is no surprise that disasters occurred. The Lady Elgin, a side-wheel steamer that sank off the coast of Illinois in 1860 carrying approximately four hundred passengers, is perhaps the most notorious. Despite the dangers inherent in the Great Lakes shipping business, water transportation transformed Milwaukee from a fur trading post into a bustling port city. However, as the epicenter of American wheat distribution shifted north toward the Twin Cities and railroads absorbed a considerable amount of the cargo transportation market, lake traffic around Milwaukee changed.[5]

Cargo and passenger transport on the lakes continued into the twentieth century, but in new capacities. As a result of the increased use of railroads in the United States, water vessels specializing in the transportation of railroad cars became common visitors to the Port of Milwaukee. Car ferries appeared on the Great Lakes during the mid-nineteenth century, but their use expanded considerably in the early twentieth century, including added accommodations for cross-lake passengers. The most significant shift in water transportation during the twentieth century occurred with the opening of the St. Lawrence Seaway. Mayor Daniel Hoan and others around the Great Lakes promoted the creation of a large scale lock system to bring international ocean commerce into Milwaukee’s lap as a potential economic windfall. The Seaway’s most significant impact, however, would not be economic, but ecological. When the St. Lawrence Seaway opened in 1959, ocean freighters—larger than any ships that had previously travelled the Great Lakes—struggled to maneuver through the constricted lock system. In the following decades, hopes for Milwaukee to become an international port diminished. Smaller cargo freighters continued to utilize the Seaway, but the most significant impact they had was introducing invasive species into the Great Lakes through their ballast water.[6]

Looking out into Milwaukee’s harbor, one can still glimpse the occasional cargo freighter, but fishing charters, sailboats, and novelty schooners like the S/V Denis Sullivan are much more common. On the rivers, leisure crafts like pontoons, kayaks, and paddle-taverns have replaced cargo ships as the dominant vessels. Water transportation continues to play a significant role in the Greater Milwaukee area, but that role has shifted to be more recreational than economic.[7]

Footnotes [+]

- ^ John Gurda, Making of Milwaukee (Menomonee Falls, WI: Burton & Mayer, 2008), 8; John Gurda, Milwaukee: A City Built On Water (Madison, WI: Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 2018), 7. “Transportation,” Milwaukee Public Museum website, accessed August 14, 2019.

- ^ “European Exploration in Wisconsin,” Wisconsin Historical Society website, accessed August 14, 2019; “The Search for Le Griffon,” The Digital Archaeological Record, accessed August 14, 2019; Gurda, Making of Milwaukee, 5.

- ^ Gurda, Making of Milwaukee, 16, 24, 44, 51; Gurda, Milwaukee: A City Built on Water, 19, 27, 39-46; Leah Dobkin, Soul of a Port (Charleston, SC: History Press, 2010), 29: Increase Lapham, A Documentary History of the Milwaukee and Rock River Canal (Milwaukee: Office of the Advertiser, 1840), accessed August 13, 2019.

- ^ “Mitchell, Alexander 1817-1887,” Wisconsin Historical Society, accessed August 13, 2019.

- ^ Gurda, Milwaukee: A City Built on Water, 21, 29; Carl Baher, “Clybourn Was Once the City’s Main Street,” Urban Milwaukee, October 2, 2015, accessed August 15, 2019; Gurda, Making of Milwaukee, 72, 75-76, 78; Bethany Harding, “Lady Elgin,” Encyclopedia of Milwaukee, edited by Margo Anderson and Amanda I. Seligman, accessed August 16, 2019.

- ^ George W. Hilton, The Great Lakes Car Ferries (Berkeley, CA: Howell-North Books, 1962), 1-5.; Dan Egan, The Death and Life of the Great Lakes (New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company, 2017), 23, 29; Floyd J. Stachowski, “The Political Career of Daniel Webster Hoan” (Ph.D. diss., Northwestern University, 1966), 215.

- ^ “Sailing Vessel: Denis Sullivan,” Discovery World website, accessed August 17, 2019; “The Best of the Best Party Boat Route,” Milwaukee Paddle Tavern, accessed August 17, 2019.

For Further Reading

Dobkin, Leah. Soul of a Port: The History and Evolution of the Port of Milwaukee. Charleston, S.C.: The History Press, 2010.

Egan, Dan. The Death and Life of the Great Lakes. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company, 2017.

Gurda, John. Making of Milwaukee. Menomonee Falls, WI: Burton & Mayer, 2008.

Gurda, John. Milwaukee: A City Built on Water. Madison, WI: Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 2018.

Johnson, Jean Lindsay. When Midwest Millionaires Lived like Kings. Milwaukee: Jean Lindsay Johnson, 1981.

Wisconsin Marine Historical Society. Maritime Milwaukee. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing Co., 2011.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.