Who is a Jew? The difficulties of definition were apparent in two recent publications. In 2011, the Milwaukee Jewish Federation commissioned a study which concluded that there were approximately 25,600 Jews in the Milwaukee metropolitan area.[1] A 2013 Milwaukee Magazine article, using a measure of synagogue membership, said there were fewer than 9,000.[2] Defining Jews and Judaism goes beyond religious observance and encompasses a shared history, ethnicity, and most importantly, self-identification. This essay will define Jews broadly and look at the history and current status of the Jewish experience in the Milwaukee metropolitan area from the 1840s to 2015.

The authoritative Encyclopedia Judaica distinguishes between “Judaism,” as the “religion, philosophy and way of life of the Jews,” and “Torah,” as classical sources of “doctrine,” and “teaching,” which call attention to “divine, revelatory aspects.”[3] Shared beliefs and common history include: monotheism; shared peoplehood and common ancestry from the Biblical figures of Abraham, Isaac, Jacob (and their wives Sarah, Rebecca, and Rachel); the Exodus from slavery in Egypt; the giving of the Torah at Mount Sinai; entry into the land of Israel; the codification of Torah commandments into halachah (Jewish law) through the rabbinical discourses of the Mishnah, Gemarah, and later writings; and a subsequent shared history of a scattered people throughout the world to the present day. Judaism follows a lunar calendar to determine its holiday dates. Jews are tied not only to their historical origins but also to their seasons.[4]

In the mid-nineteenth century and into modern times, reinterpretations of Jewish law led to four distinct movements within Judaism. These include Orthodox, Conservative, Reform, and Reconstructionism, all represented in Milwaukee today.

Immigration Patterns to Milwaukee

When Europeans began to settle Southeastern Wisconsin in the 1830s, Jewish pioneers were not far behind. Unlike other Midwestern communities (notably Cleveland), they did not come as an organized religious group, but rather as individuals or in small family units. Arriving from German-speaking states and the Austro-Hungarian Empire, with surnames like Shoyer, Neustadtl, Mack, Adler, Weil, and Heller, in the early 1840s they established businesses and professions in the growing city of Milwaukee. The first known Rosh Hashanah (Jewish New Year) service was held in 1847, and in 1850, Congregation Imanu-El was established, serving some seventy Jewish families.

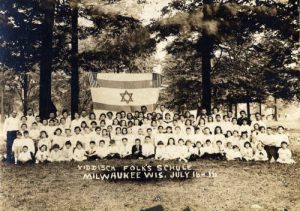

The first settlers were part of the nineteenth century wave of immigrants from Central Europe, most speaking German, who found the Milwaukee area welcoming in language, offering economic opportunities, and lacking the prejudice and legal hindrances they experienced in their former homelands. By the 1880s they and their children had established a comfortable existence, maintaining their Jewish identity, yet mingling easily with the larger community. The Jewish population was a little over 2,000 in a city whose population in 1880 topped 115,000. Pogroms (legal, government-sponsored riots), intense poverty, discrimination, and the lack of opportunity in Eastern Europe led to the next wave of immigration to the United States and also to Milwaukee. From 1880 until restrictive immigration laws were enacted in the 1920s, more than 2.5 million Jews entered the United States. Milwaukee’s Jewish population grew to 20,000, the eleventh largest concentration of Jews in the United States. Adding to independent immigration was a Jewish organization called the Industrial Removal Office (IRO), headquartered in New York with agents throughout the Midwest and sparsely populated West, which found employment for immigrants living in crowded East Coast tenements. The IRO also provided train fare for these workers and their families and settled over 2,000 in Milwaukee.

The next wave of immigrants arrived in Milwaukee when the Nazi party came to power in Germany in the 1930s. Smaller in size, but important in their later influence, these initially impoverished families drew upon familial connections to obtain affidavits to come to Southeast Wisconsin. After the close of World War II, several hundred more, this time survivors of the Holocaust, were able to settle in the area. In the last part of the twentieth century, the most notable group has been a large cohort from the former Soviet Union, arriving from the late 1970s through the 1990s.

As the Jewish community added to its numbers, it also changed its settlement patterns. Beginning with other early settlers, German-speaking Jews in the nineteenth century settled downtown and on the East Side. The larger wave of Eastern European Jews were crowded into the area mostly west of the Milwaukee River known as the Haymarket, until many moved, beginning in the 1920s, to the Sherman Park neighborhood. By the end of the twentieth and into the twenty-first century, much of the Jewish community was concentrated in the Upper East Side, Shorewood, and the northern suburbs as far as Mequon in Ozaukee County. A pocket of congregants remains on Milwaukee’s West Side, led by Rabbi Michel Twerski, of a nationally known family of Orthodox rabbis.

Community

A group of Jewish settlers typically becomes a community when it buys land for a cemetery—by religious tenet one must be buried separately from one’s non-Jewish neighbors—and the early Milwaukee settlers were no exception: a plot on Hopkins St. was purchased in 1848. Synagogues came a bit later, as did charitable organizations, fraternal groups, and educational structures. As new waves of immigrants came to Milwaukee, their needs were met through these groups. At the same time, growing nativism encouraged the creation of social and fraternal organizations when the existing clubs, associations, and neighborhoods restricted Jewish admission. By the twentieth century, the proliferation of synagogues reflected the earlier, German speaking but now fully assimilated and American-born “East Siders” and the West Side Eastern Europeans, whose smaller, more Orthodox synagogues tended to fall along the lines of their places of origin in the “old country.” In the most recent edition of A Guide to Jewish Wisconsin[5] there are nineteen synagogues listed in the metropolitan area, which includes Mequon and Waukesha (two are at senior living facilities). In addition, there is one in Sheboygan, one in Racine, and three in Kenosha. Represented are all the branches of Judaism mentioned above, including several Orthodox congregations affiliated with the Chabad movement.

The Abraham Lincoln House, built in 1911 to replace an older structure and funded by the sales of Lizzie Black Kander’s Settlement Cookbook, was a meeting place for scores of community organizations, ranging from cooking classes for girls, English language classes for new immigrants, drama and sports for youth, communal baths, and political groups, including the growing Zionist movement and the Milwaukee brand of socialism.[6] Later proceeds of the cookbook led to modernized buildings on Prospect Avenue and to its present Karl Jewish Community Campus in Whitefish Bay, where it continues to provide social, athletic, and cultural programming. Community newspapers in German and Yiddish were short-lived. In 1921, the Wisconsin Jewish Chronicle was established as a weekly; it remains the community’s voice to this day as a monthly publication and online.

At the turn of the twentieth century, to counter non-productive and competitive fundraising, the Federated Jewish Charities was established. Today known as the Milwaukee Jewish Federation (MJF), it oversees coordinated fundraising and programming for social welfare agencies, educational institutions, outreach to all age groups, community relations within and outside the Jewish community and provides a voice both explaining and promoting the State of Israel in the metropolitan area. The MJF today has a general fundraising drive which serves local community needs (described below), the Jewish Agency for Israel, and the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, which aids Jews in need throughout the world. It also maintains the Jewish Community Foundation for charitable and estate planning activities, which in 2013-2014 distributed over $16 million.[7]

The MJF is part of a North American consortium of Jewish federations and has been highly regarded for its leadership. Of note was Melvin Zaret (1918-2010), who served as executive director for nearly thirty years and is credited with creating a Milwaukee model for professional and lay partnership.[8] In 2012, Hannah Rosenthal became Milwaukee’s first woman chief executive officer of the MJF, although several women had been lay presidents before her, including Esther Leah Ritz and Betsy Green. Rosenthal had previously served in President Barack Obama’s administration in the State Department.

As each wave of immigration had different social, educational, and welfare needs, the MJF adapted to changing circumstances. For example, it supported the growth of Mount Sinai Hospital in the twentieth century, when Jewish doctors had difficulty finding positions, although the hospital treated the whole community. When employment opportunities, changes in neighborhood, and the “business” of hospitals evolved, Mount Sinai merged with other hospital systems and is no longer a beneficiary agency. The Hebrew Relief Society (founded in 1867) is currently known as the Jewish Family Services. It has assisted every generation of Jewish immigrants, and today it helps a wide clientele, Jewish and non-Jewish, with social services for families in need.

During the last half of the twentieth century and into the twenty-first, Jewish day school education grew significantly, from the first all-day school with a double curriculum in 1960 to three elementary schools, two high schools, and two pre-schools. The MJF has a special department, the Coalition for Jewish Learning (formerly the Bureau of Jewish Education, founded 1944), which provides materials and workshops to support educational programming in Milwaukee, not only to the day schools, but also to the supplementary schools at the synagogues which provide after-school education to their congregants’ children. The MJF also supports Hillel Milwaukee (opened 1972), which provides Jewish programming to university students on the various campuses in the metropolitan area.

Attention to the aged began in 1905 with a small home for indigent seniors and continues today on several campuses for all income levels, reflecting a population that is aging relative to the general population. The Jewish Home and Care Center in Milwaukee and the Sarah Chudnow Campus in Mequon allows its residents to live independently or to receive high levels of assistance, depending on their physical and emotional needs, all within a Jewish setting.[9]

Founded in 1938 as an independent agency to combat anti-Semitism, the Milwaukee Jewish Council for Community Relations is an integral part of the MJF. It responds not only to anti-Semitism but also reaches out to ethnic and religious groups throughout the metropolitan area to promote social justice and to foster cooperative programming and interfaith activities.

The Nathan and Esther Pelz Holocaust Education and Resource Center serves the Jewish and non-Jewish community with programming, speakers, and a print and media library for educators and students throughout the state. A recent addition to Jewish institutions in the area is the Jewish Museum Milwaukee, which opened in 2008. It presents Judaism and Jewish history through the lens of the Milwaukee Jewish experience to students and adults, Jewish and non-Jewish alike.

Making a Living

In central and eastern Europe, Jews were forbidden to own land, marry when they chose to, receive educations at secular institutions, and enter business or craft guilds. For that reason, certain areas of employment, often portable from one location to another, have long been associated with Jews, including anything to do with the making and selling of clothing; food and its associated businesses; and arts and entertainment, including writing, theater, and music. In the New World, including Milwaukee, Jewish immigrants and their families began and maintained the same ways of making a living. Early settlers, after plying their wares via pushcarts, set up stores along Grand (later Wisconsin) Avenue and 3rd Street, North Avenue, and later along Burleigh Avenue. Some of these grew into Gimbels, the Boston Store, Goldmann’s, and Schuster’s, all department stores. Of these, only the Boston Store remains, although no longer owned by its original founders. David Adler & Sons manufactured clothing and employed many Jewish workers in the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century, while Florence Eiseman designed children’s clothes sold by high-end department stores throughout the United States. The Kohl’s department store chain grew from one small grocery store (which opened in 1927) in a neighborhood where there were once over one hundred small food shops, bakeries, butchers, and delicatessens. There was also a thriving junk and recycling industry.

Major innovative businesses were conceived by Milwaukee Jews, including Aldrich Chemical Company by Alfred Bader; Harry Soref and his family, who created Master Lock; George Bursak, whose Bursa-Fill company devised a way of making one-use packages, leading to more sanitary methods in hospitals (as well as ketchup and mustard packets); and aeronautic innovation from Nathaniel Zelazo’s Astronautics. Manpower, a local employment agency which became a world-wide leader in temporary hiring, was a post-World War II brainchild of Elmer Winter and Aaron Scheinfeld. Max Karl created MGIC, a mortgage-financing company in the 1950s. Joseph Zilber established a real estate empire and the Peck family thrived in the meatpacking industry. Today, many of these names are seen in the world of philanthropy, arts, and sports: the Marcus Center for the Performing Arts; the Peck School of the Arts, the Lubar School of Business, and the Zelazo Center, all at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee; the Zilber and Helfaer buildings on the Marquette University campus; and the Karl Jewish Community Center. In 1970, Allan “Bud” Selig was instrumental in bringing baseball back to Milwaukee; he later became Commissioner of Major League Baseball. Herb Kohl owned the Milwaukee Bucks basketball team for many years. The Zucker brothers and Jim Abrahams, Shorewood High School graduates, created successful comedies in Hollywood, and Dick Chudnow created the Comedy Sportz franchise, now with improvisational venues all over the world.

Beyond business, Jews entered the world of medicine, politics, and law. The Harry Waisman test and diet for phenylketonuria is used worldwide in the field of developmental disabilities. The community is also noted for many well-known attorneys. Joseph Padway, an attorney, legislator, and labor advocate, was critical in the passage of key labor legislation in the 1920s and 1930s. James Shellow, a constitutional lawyer, defended, among others, Father James Groppi during the Civil Rights era in the 1960s. In the new century, Ann Jacobs was honored as the 2010 Wisconsin Woman in the Law, and federal judge Lynn Adelman has presided over important constitutional issues. In politics, for many years Wisconsin was represented by two Jewish senators: Herb Kohl (a Milwaukee native) and Russ Feingold (born in Janesville, but a Marquette University law professor for a time and whose sister, Dena Feingold, was Wisconsin’s first female rabbi). Both Sandy Pasch and Jonathan Brostoff, who are Jewish, have served in the state assembly.

Zionism and the Milwaukee Ties to the State of Israel

Although exiled after the Roman destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE, small numbers of Jews remained in the land of Israel in four cities: Tiberias, Tzfat, Jerusalem, and Hebron.[10] In daily prayers, poetry, and literature, Jews in the diaspora spoke of their yearning to return to their homeland. In the nineteenth century, reflecting European nationalism and the work of Theodor Herzl and others, Jews throughout the world embraced political Zionism, that is, the hope of establishing a legitimate state in what was now called Palestine. Milwaukee Jews were no different. The first known group was founded in 1899, the Judah Halevi Gate of the Knights of Zion. In the early part of the twentieth century, when Goldie Mabowehz (later Golda Meir, prime minister of Israel from 1969-1974) was a young Milwaukeean, there were no fewer than twenty organizations that embraced different approaches to how that potential state would operate, from communist to capitalist and from secular to religious. (Such diversity of opinion about the state of Israel persists among Milwaukee Jews to this day.)

Men’s and women’s groups, youth groups, singing societies, and Hebrew classes—all were active by the time the United Nations voted for a partition approving a Jewish state in Palestine in 1947. Subsequent to the founding of the Jewish state, Milwaukee has been acknowledged as a leading contributor, for its size, to overseas campaigns to support Israel. Every year, sponsored by the MJF and other organizations, the Jewish community commemorates the “Yamim” or days: Yom Hashoah, remembering the Holocaust; Yom Hazikaron, remembering lost Israeli lives in wars; and Yom Ha’atzma’ut, Israeli Independence Day. The MJF Israel Center programming had 2,700 participants in 2014.

Individuals from Milwaukee played prominent roles nationally and internationally. For example, the late Martin Stein was important in the immigration of Ethiopian Jews to Israel. Bruce Arbit serves on the Executive Committee of the Jewish Agency for Israel. Many Milwaukee community members, from students to senior citizens, have visited Israel, while others have children who immigrated to Israel. The MJF, along with the Jewish communities of Madison, St. Paul, and Tulsa, participate in the Partnership Together program, which links these cities with the Tiberias region of Israel. This exchange program, along with the Community Shlichut [Emissary] program, in which an Israeli professional programmer and his or her family lives in Milwaukee and initiates local programming, has allowed Milwaukeeans to get to know Israelis on a personal level. These friendships have persisted over decades, linking Milwaukee’s Jewish community to a larger world.

Footnotes [+]

- ^ Stephen Percy, The Jewish Community Study of Greater Milwaukee 2011 (Milwaukee: Milwaukee Jewish Federation, 2011, revised 2015), last accessed May 14, 2017.

- ^ Matt Hrodey, “The New Faith,” Milwaukee Magazine (August 2013): 48, http://www.milwaukeemag.com/article/412013-TheNewFaith, accessed August 2015.

- ^ Louis Jacobs, “Judaism,” Encyclopaedia Judaica, ed. Michael Berenbaum and Fred Skolnik. 2nd ed., vol. 11 (Detroit: Macmillan Reference USA, 2007), 511-520, last accessed May 14, 2017.

- ^ Judaism 101, last accessed May 14, 2017.

- ^ A Guide to Jewish Wisconsin (Milwaukee: Milwaukee Jewish Federation, 2014), last accessed May 14, 2017.

- ^ An extensive list of early Jewish communal organizations can be found in the appendices of Louis J. Switchkow and Lloyd P. Gartner, The History of the Jews of Milwaukee (Philadelphia, PA: Jewish Publication Society of America, 1963), 493-519.

- ^ Milwaukee Jewish Federation, 2013-2014 Annual Report to the Community (Milwaukee: Milwaukee Jewish Federation, June 2014), last accessed May 14, 2017.

- ^ Leon Cohen , “Zaret, Lover of History, Made History in Jewish Milwaukee,” Wisconsin Jewish Chronicle, June 28, 2010, http://www.jewishchronicle.org/article.php?article_id=12227, accessed August 2015, now available at http://www.jewishchronicle.org/2010/06/28/zaret-lover-of-history-made-history-in-jewish-milwaukee/, last accessed September 12, 2017.

- ^ In 2016, these two facilities, along with Chai Point Senior Living, were rebranded as “Ovation Communities.” See Ron Golub, “Communities Become Ovation,” Wisconsin Jewish Chronicle, November 30, 2016, last accessed May 14, 2017.

- ^ Martin Gilbert, Routledge Atlas of the Arab-Israeli Conflict, 10th edition (New York: Routledge, 2012), 23 and 24, last accessed May 14, 2017.

For Further Reading

Gurda, John. One People, Many Paths: A History of Jewish Milwaukee. Milwaukee: Jewish Museum Milwaukee, 2009.

Switchkow, Louis J., and Lloyd P. Gartner. The History of the Jews of Milwaukee. Philadelphia, PA: Jewish Publication Society of America, 1963.

Zaret, Melvin S. “Milwaukee.” In Encyclopaedia Judaica, 2nd ed., vol. 14, edited by Michael Berenbaum and Fred Skolnik. Detroit, MI: Macmillan Reference USA, 2007. 261-263. Gale Virtual Reference Library. April 15, 2015.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.