Throughout the twentieth century, the A.O. Smith manufacturing plant was a site of intense activity. Housed on a sprawling multi-acre, multi-block site on the city’s North Side, A.O. Smith mass-produced automobile frames, turning out 100 million by 1982. Such industrial activity transformed the neighborhood surrounding the plant, as the company, which at its peak employed close to 10,000 workers, had its own power plant, hospital, and fire station. On the plant’s periphery stood streets upon streets of working-class bungalow homes and restaurants that cropped up to serve the workers who found steady, well-paying work at A.O. Smith.[1]

The modesty of these workers’ homes contrasted starkly with both the sheer size of A.O. Smith’s production plant as well as to the architecture of the buildings that housed the company’s management and research teams. An ornate, two-story red brick building, completed in 1910, served as the company’s headquarters. The seven-story Research & Engineering building, completed in 1930 by the Chicago-based architectural firm Holabird and Root, was even more impressive. Featuring full curtain walls of windows, the structure was one of the first multi-story buildings constructed in the United States in the modernist International Style. Here was a true monument to the importance of manufacturing to Milwaukee’s economic health.[2]

By the early twenty-first century both of these buildings sat empty, their windows boarded up. In 1997, A.O. Smith sold its U.S. business to Michigan-based Tower Automotive. Just eight years later, Tower filed for bankruptcy and began phasing out production at the plant. The final Tower employee clocked out in November 2009. The site quickly fell into disrepair, as did the homes and businesses that surrounded the once bustling landscape. In December 2009, the City of Milwaukee took ownership of the troubled property and began the demolition process.[3]

Yet less than one year later it appeared as if some of the site was to be salvaged. In March 2010, Wisconsin Governor Jim Doyle announced that the Spanish firm Talgo planned to set up shop in one of the remaining Tower buildings. Talgo planned to use the site’s industrial infrastructure to manufacture high-speed rail cars. A change in political leadership, however, led to Talgo’s exit from the city: incoming Republican Governor Scott Walker, elected in late 2010, voided the contract put forward by the outgoing Democratic Doyle administration. The site, rebranded “Century City” by the City of Milwaukee in 2013, struggled to find new tenants. But city officials still hoped that developers would come to embrace this malleable urban canvas.[4]

This example of the A.O. Smith/Tower Automotive site highlights the complicated legacies of Milwaukee’s industrial past. Once known as the “Machine Shop of the World,” the city has seen the manufacturing companies that used to turn out countless products shutter their doors forever. This story of deindustrialization—and the global economic forces that informed this process—has undoubtedly exacted a profound human toll. By the early twenty-first century, Milwaukee had lost more than two out every three factory jobs it had in 1970; more than 80,000 jobs disappeared. This recent history informs the high rates of poverty and joblessness that continue to plague the city.[5]

As this troubled environment defines contemporary Milwaukee, buildings like those that remain on the A.O. Smith/Tower Automotive site take on a charged significance. These industrial landscapes embody the troubled histories that mark Milwaukee’s rise and fall as a manufacturing center. In many cases, the buildings that drove this growth still stand—often in various states of usage and physical condition—while the jobs they once provided left years ago. These structures, in other words, serve as physical reminders of a past marked by economic trauma. And, as seen in the A.O. Smith/Tower Automotive example, efforts to address this address this painful history and “rebrand” the city for the twenty-first century often come down to one question: what to ultimately do with such an unsettled built environment?

This entry documents how Milwaukee has dealt with this question. It offers a visual history of the city’s industrial landscapes and the buildings that defined such spaces. On the one hand, Milwaukee’s status as a “post-industrial” city is greatly exaggerated; industry still plays a decisive role in shaping Milwaukee’s built environment. Yet much of this environment remains in flux. Milwaukee’s industrial landscapes, and their meanings, have changed over time. The structures that define Milwaukee’s industrial landscape transformed from symbols of industrial prowess to sad reminders of a past that will never return, and, finally, to spaces of potential economic redevelopment. The industrial landscapes of Milwaukee do more than physically retell the city’s volatile history. These constantly evolving environments also provide glimpses of Milwaukee’s future.

A quick drive through Menomonee Valley , the historical epicenter of industrial activity in Milwaukee, makes it clear that, despite the devastation wrought by deindustrialization, the city remains a site of industrial production. This is particularly apparent when one views the massive Falk Corporation compound, which, by the early twenty-first century, sprawled out over 1.1 million square feet of space. At the heart of this site is a 70,000 square foot factory, completed in 1900, that produces industrial gears. The facility’s smokestack—emblazoned with the company name—remains a landmark that can be seen by drivers on nearby I-94.[6]

Although Falk began as a brewery in 1856, by 1892 the company had shifted its focus to become a general-purpose machine shop. By 1900, the firm’s Menomonee Valley site was operational. Here, an office building designed by the esteemed architectural firm Eschweiler & Eschweiler shared space with a machine shop, a pattern shop, and a 20,000-square-foot steel foundry.[7]

By the early twentieth century, Falk was one of the largest manufacturers of precision industrial gears in the United States. As gear-driven machines continued to drive Milwaukee’s economy, the company expanded its footprint within the Menomonee Valley. Work provided by two World Wars added more buildings to the Falk compound, as did the post-World War II economic boom. The company even expanded during the 1970s: between 1970 and 1974, for example, the plant’s main production facility grew by 100,000 square feet. By the late twentieth century the compound was the epitome of a large-scale industrial landscape, replete with massive, utilitarian buildings and hundreds of working-class employees.[8]

A similar story of industrial growth unfolded in nearby Miller Valley. Here, since 1855, Miller Brewing Company has been a global leader in beer production. On a campus consisting of 82 acres of land and 76 buildings, Miller produces up to 8.5 million barrels of beer each year. In very real ways, the construction of these buildings mirrored moments of economic growth in Milwaukee. In 1887, as the city’s industrial activity was reaching a fever pitch, Miller installed a new brewhouse, new icehouses, and a new milling house. A series of stockhouses designed to ferment and age beer were constructed in 1892, 1894, and 1904, while a new condenser building meant to house refrigeration equipment went up in 1897. A bottling house soon followed in 1901, and a rebuilt wash house opened in 1902. These multi-story buildings, done in brick and often featuring elaborate detailing and ornamental archways, made it clear just how important beer had become for the city of Milwaukee.[9]

A similar pattern of physical growth occurred following the end of World War II. As a sense of postwar affluence settled over the city, Miller—beginning in 1948—constructed a series of updated buildings, including a new three-kettle brewhouse (1949), a new administration building (1951), and the “I” House, a 200-foot tall stockhouse that towered over the rest of the compound. Unlike their predecessors, these buildings embraced what historian John Gurda has termed a “modestly stated modernism.” Stripped of any trace of adornment, these machines-for-working redefined the aesthetic of the brewery while highlighting the company’s desire to brew more and more beer. And brew it did: between 1946 and 1952, Miller’s sales increased by 379 percent.[10]

Despite the impact of Miller on Milwaukee’s built environment, it is the Allen-Bradley clock tower that remains the most iconic physical symbol of the city’s industrial heritage. The octagon-shaped clock, designed by architect Fitzhugh Scott, was unveiled on Halloween night in 1962. Until 2010, the “Polish Moon”—for much of its history, the clock has looked down on a predominantly Polish south-side neighborhood—was the largest four-sided clock in the world, standing at 218 feet, with clock faces measuring approximately 40 feet in diameter.[11]

In 1903, Lynde Bradley and Dr. Stanton Allen formed the Compression Rheostat Company. Six years later they renamed their endeavor the Allen-Bradley Company. Producing industrial controls, the fledgling company came from modest beginnings: in 1914 the firm was renting space in someone else’s machine shop in the Walker’s Point neighborhood. But World War I brought about a surge in orders. In 1918 the pair bought out the property owner and started work on a three-story addition to the space. By 1920, the Allen-Bradley plant featured 41,725 square feet of space and employed 218 people.[12]

The company continued to physically grow during the booming 1920s. In 1928, the company dedicated a seven-story addition that included a reading room, marble bathrooms, and a rooftop deck featuring space for dancing, badminton courts, and nets to catch the practice shots of those within the company who played golf. A similar building boom followed the end of World War II: by 1950, 2,959 people labored within a plant that was now 675,847 square feet. By 1964, these numbers had grown to 6,774 employees and 2,886,275 square feet of factory space. As of 2016, the building—with such features as an elevated walkway that spans the entirety of Second Street—remains an imposing presence in the Walker’s Point neighborhood.[13]

Yet during the 1970s, Allen-Bradley shifted over 1,200 production jobs from Milwaukee to El Paso, Texas, and Greensboro, North Carolina. As the global economy continued to expand, in 1985 the firm was bought by Rockwell International, which shifted production of its electronics components line to Juarez, Mexico. By the early twenty-first century the company was known as Rockwell Automation. Rockwell Automation quickly used the factory space provided by previous downsizing campaigns to become a global leader in the production of factory automation equipment, making products with fewer and fewer workers. Even the famed Allen-Bradley clock tower had to face the realities of increased global competition: in 2010 it lost its status as the world’s tallest four-faced clock. As of 2016, the Mecca Royal Clock Hotel Tower in Saudi Arabia holds the world record. This clock, which overlooks Mecca’s Grand Mosque, stands at 1,970 feet. Its clock faces are 140 feet in diameter.[14]

Allis-Chalmers Company

Allen-Bradley is not the only firm that has had to adapt to meet the imperatives of an evolving global economy. In 2005, the Falk Corporation was acquired by Rexnord Corporation, which had been bought by the Washington, DC-based Carlyle Group in 2002 and then reorganized under their parent company, RBS Global, Inc. Since its postwar peak in sales, Miller Brewing Company has faced stiff competition from a changing food and beverage market. In 1966, the brewery was sold to Maryland-based W.R. Grace and Company, which, just three years later, sold the Miller brand to Philip Morris. In 2002, the company was bought by London-based South African Breweries (SAB), becoming SABMiller. SABMiller merged with rival Coors Brewing Company in 2007, and the new firm made the decision to locate their headquarters not in Milwaukee, but in Chicago.

Despite efforts to adapt to the realities of a truly global economy, many Milwaukee area firms struggled to find a place within this new economic order. For these companies, plant closure—followed by demolition—often became the only way to deal with such developments. Illustrative of this strategy is Allis-Chalmers, a firm that throughout its history made a variety of heavy machinery, with an emphasis on agricultural equipment. The company, though founded in 1901 as the Allis-Chalmers Company, did not really come into its own until a 1913 reorganization rebranded the firm as Allis-Chalmers Manufacturing Company. Under the leadership of Otto Falk, the company quickly made the production of farm tractors a crucial piece of its business strategy.[15]

Under Falk, the company also made their West Allis plant the center of activity. Located just west of Milwaukee, this facility opened in 1902 and quickly expanded from 110 acres to over 160 acres. The complex featured a workspace of over 4,100,000 feet where, by 1920, over 5,500 workers toiled. At its peak, the plant employed close to 15,000 people. A massive foundry allowed for 80,000 tons of metal to be melted and cast into parts that could weigh as much as 135 tons. To get such products out to customers, the firm relied on a network of twenty-one miles of railroad tracks and five miles of roads. From the vantage point of the twenty first century—with some of this facility now gone—it is difficult to comprehend just how sprawling the Allis-Chalmers plant truly was.[16]

Changes to the global agricultural market led to hard times for the tractor maker. The company lost $28.8 million in 1981, $207 million in 1982, and $261 million in 1984. The firm razed part of their West Allis complex in 1985 to make room for a shopping center; further demolition work followed in 1986. The company ultimately declared bankruptcy in 1987, two years after the last tractor left the plant assembly line.[17]

Selective Demolition and Adaptive Re-Use

Yet demolition did not erase the entire Allis-Chalmers industrial landscape, as a handful of the abandoned buildings were repurposed for office use. Other former industrial sites, including the Pabst Brewery complex, followed a similar strategy of “selective demolition.” Production at Pabst ceased in 1996; it was not until 2006 that an investment group headed by local entrepreneur and philanthropist Joseph Zilber began to actively redevelop the site. And what a site it was: the Pabst complex covered over twenty acres on six and one-half city blocks; when fully functioning, the site was a city-within-a-city. Structures included a German Methodist church (1872), a Brew House (1877), a Malt House (1891) and a 250,000 square foot bottling building (1900)—many done in the Cream City brick that came to define the prevailing aesthetic of industrial-era Milwaukee. A number of these structures also featured rounded-arch windows, corbelling, castellated parapets, and other forms of architectural ornamentation. As at Miller, such embellishments suggested the almost divine place of beer within the city’s late nineteenth-century economy.[18]

By 2007, however, this past was largely forgotten, subordinated to new uses. That year the demolition firm Brandenburg Industrial Service Company began tearing down selected pieces of the Pabst complex. By 2015, the renovated site looked like a monument to the drivers of the post-industrial economy. Apartments, academic institutions, restaurants, and other service industry-related firms employed adaptive re-use to redefine the brewery for the twenty-first century. The former keg house became the residential Blue Ribbon Brewery Lofts, while the plant’s brewing facility became Brewhouse Inn and Suites, with the complex’s stunning copper brew kettles integrated into the hotel’s interior design. Jackson’s Blue Ribbon Pub & Grill opened in the building next to the inn. The complex also houses facilities for the Cardinal Stritch University College of Education and Leadership and the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Zilber School of Public Health.[19]

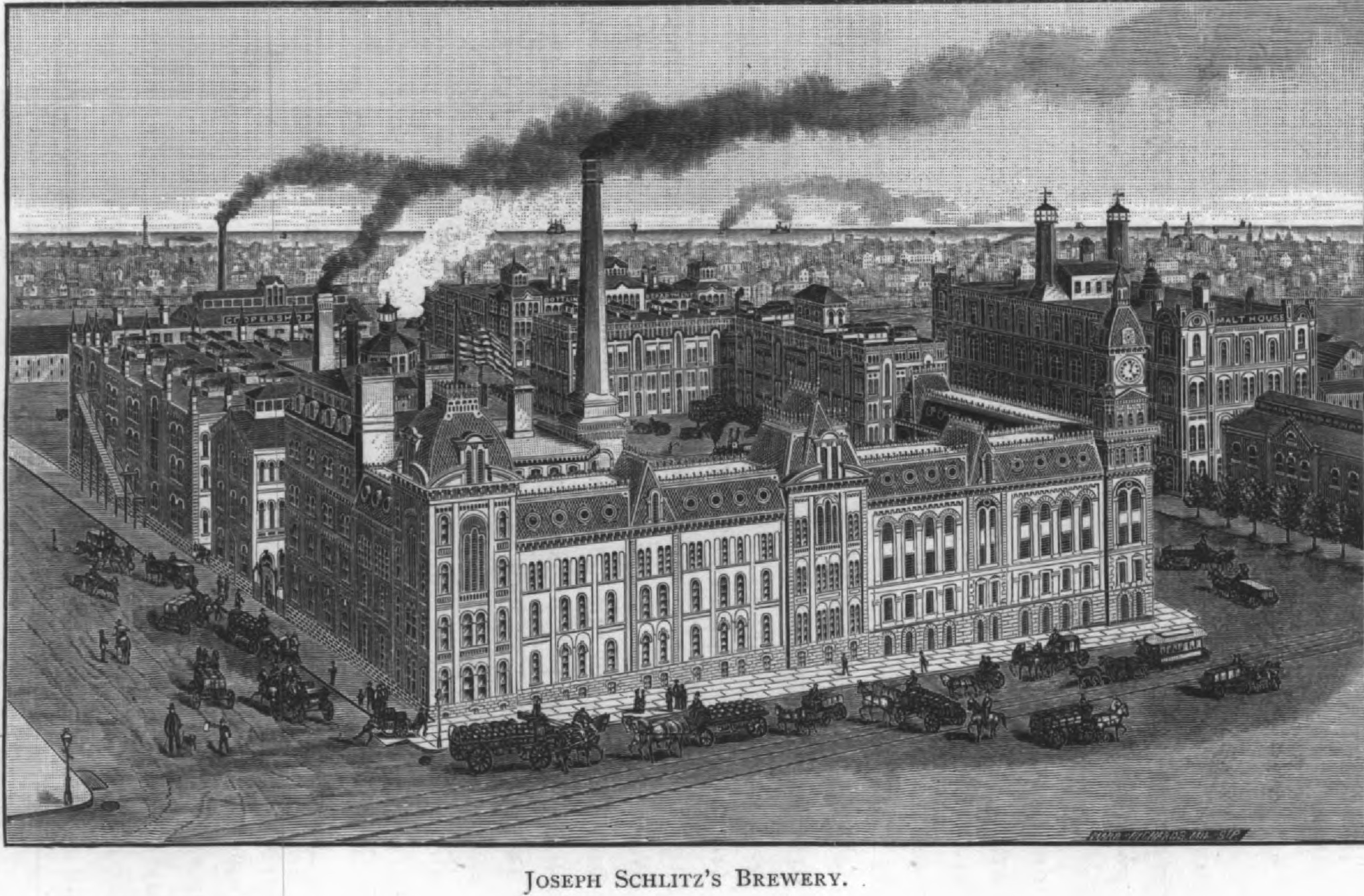

Following similar acts of selective demolition, the campuses of other historic Milwaukee breweries became sites known for adaptive re-use. During the late twentieth century, the nearby Schlitz brewery (founded in 1849) was recast as “Schlitz Park,” a mixed-used office park. By the early twenty-first century, the buildings once associated with Blatz Beer (founded in 1846) also took on a variety of functions. Blatz’s main brewhouse, constructed in 1901, now houses condominiums, while the company’s art deco-inspired bottling plant is now the Milwaukee School of Engineering’s Campus Center. Within the latter structure, there is no information provided as to the former use of the building.[20]

In 2009, A.O. Smith, now far removed from producing automobile frames, entered the water purification industry with the creation of A.O. Smith (Shanghai) Water Treatment Products Co. Ltd. This new company provides reverse osmosis water treatment and water filtration products to the China residential and commercial markets. That same year, along with a number of Milwaukee-area businesses, education, and governmental leaders, A.O. Smith Executive Chairman Paul Jones co-founded the Water Council, a non-profit organization. With a stated mission of “aligning the regional freshwater research community with water-related industries,” the Council has attempted to bring these global opportunities to local entrepreneurs.[21]

In their efforts to recast Milwaukee as an international water research center, the Council has called for the creation of physical spaces dedicated to water technologies. The most prominent example of this trend is the Global Water Center, located in the Walker’s Point neighborhood at the eastern end of the Menomonee Valley. In 2013, A.O. Smith’s Paul Jones took part in the grand opening of the facility, showcasing the water treatment laboratory that his company built within the Center. Within this laboratory A.O. Smith engineers carry out controlled testing on water purification systems set to be exported to such global markets as Turkey, India, and China. Other tenants inside the Center include such companies as Badger Meter (which creates equipment addressing water flow measurement and control technology) and the Veolia Group (which specializes in waste and energy management) and such academic institutions as Marquette University and the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee (UWM). Nearby, the “Port Building” of UWM’s School of Freshwater Sciences, housed in a former Allen-Bradley-affiliated tile factory, offers the only graduate-level training dedicated to the study of freshwater sciences in the United States.[22]

Like the School of Freshwater Sciences, the Global Water Center has both repurposed and reimagined a remnant of Milwaukee’s industrial heritage. The Center resides in a building completed in 1904 and originally used by Molitor Box Company for the production of boxes. The structure was later repurposed for the storage of straps and seatbelts by Allied Canvas Products Corporation. All of this transformation is part of large vision for redevelopment within the area: the Global Water Center serves as the entry point for the Reed Street Yards, a series of remediated brownfields that now offer space for new construction for water-related endeavors.[23]

In May 2015, construction began on Water Tech One, a four-story building that received pre-certification as LEED Platinum office space. Water Tech One will be the first of a projected nine office and research buildings to be erected in the Reed Street Yards—all with an eye on attracting companies working on various water technology issues. Such efforts are helping city leaders recast Milwaukee as a global water hub, one that is on the cutting edge of freshwater research and development. Within the Reed Street Yards, then, the old industrial landscape is quickly blending with new construction. As water becomes a focal point of industry within Milwaukee, the city’s built environment will adapt to accommodate such developments. Through this process of transformation a new industrial landscape is beginning to come to life.[24]

Footnotes [+]

- ^ John Schmid, “Down to One: Last Employee to Work Final Shift in November,” Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel, September 26, 2009.

- ^ Bobby Tanzilo, “Urban Spelunking: Tower Automotive Site,” OnMilwaukee.com, January 4, 2013, last accessed January 1, 2019.

- ^ “Tower to Close Milwaukee Stamping Plants,” Milwaukee Business Journal, December 11, 2001; Tanzilo, “Urban Spelunking,” last accessed January 1, 2019.

- ^ “Governor Doyle Welcomes Talgo Assembly Facility to Milwaukee,” State of Wisconsin Press Release, March 2, 2010; Bruce Murphy, “The Twisted Tale of Talgo,” Urban Milwaukee, August 25, 2015; Arthur Thomas, “Tenants Sought for Century City Development,” Milwaukee Business News, April 15, 2016, last accessed January 1, 2019.

- ^ John Schmid, “Still Separate and Unequal: A Dream Derailed,” Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel, December 5, 2004.

- ^ Joseph L. Hazelton, “A Winding Path into the Gear Industry: Falk Corp.,” Gear Technology (July/August 2004), last accessed January 1, 2019.

- ^ John Gurda, The Making of “A Good Name in Industry”: A History of the Falk Corporation, 1892-1992 (Milwaukee: The Falk Corporation, 1991), 36, 42.

- ^ Gurda, The Making of “A Good Name in Industry,” 57-61, 101-105, 153.

- ^ John Gurda, Miller Time: A History of Miller Brewing Company, 1855-2005 (Milwaukee: Miller Brewing Company, 2005), 49, 61.

- ^ Gurda, Miller Time, 127, 134.

- ^ Jim Stingl, “Time Passes Allen-Bradley Clock Tower,” Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel, August 24, 2010.

- ^ The Allen-Bradley Story (Milwaukee: The Allen-Bradley Company, 1965), 45.

- ^ John Gurda, The Making of Milwaukee (Milwaukee: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 1999), 244; The Allen-Bradley Story, 45.

- ^ John M. McCarthy, Making Milwaukee Mightier: Planning and the Politics of Growth, 1910-1960 (DeKalb, IL: Northern Illinois University Press, 2009), 220; Gurda, The Making of Milwaukee, 422; Stingl, “Time Passes by Allen-Bradley Clock Tower.”

- ^ Charles H. Wendel, The Allis-Chalmers Story (Sarasota, FL: Crestline Publishing Co., 1988), 13-16.

- ^ Austin Frederick, “Austin-Chalmers Factory Complexes,” https://austinfrederick.wordpress.com/2012/05/31/allis-chalmers-factory-complexes/, last accessed 2016.

- ^ Gurda, The Making of Milwaukee, 417; McCarthy, Making Milwaukee Mightier, 69.

- ^ Tara Deering, “Demolition of Historic Pabst Brewery in Milwaukee,” Construction Equipment website, May 7, 2007, last accessed January 1, 2019; City of Milwaukee Historic Designation Study Report: Pabst Brewing Company, City of Milwaukee website, July 24, 2003,, last accessed January 1, 2019

- ^ Deering, “Demolition of Historic Pabst Brewery in Milwaukee”; Tom Daykin, “Pabst Brewery Transformation in Next Phase,” Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel, October 16, 2011.

- ^ Tom Daykin, “Grunau Plans $20 Million in Additions to Downtown’s Schlitz Park,” Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel, August 6, 2015; “Property Details,” Ogden.com website, last accessed January 1, 2019.

- ^ “Celebrating 140 Years,” A.O. Smith website, last accessed January 1, 2019; “About Us,” The Water Council website, last accessed January 1, 2019.

- ^ “Global Water Center Is Open,” Milwaukee Business News, September 12, 2013, last accessed January 1, 2019; “Facilities, Equipment & Labs,” University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee School of Freshwater Sciences, UWM website, last accessed January 1, 2019.

- ^ Author interview with Kristen Leffelman, May 13, 2016.

- ^ Sean Ryan, “Reed Street Yards Puts the ‘Why’ into Where Water Tech Companies Are Moving,” Milwaukee Business Journal, August 6, 2015, last accessed January 1, 2019.

For Further Reading

Cochran, Thomas C. The Pabst Brewing Company: The History of an American Business. Cleveland, OH: BeerBooks.com, 2006, originally published in 1948.

Gurda, John. Miller Time: A History of Miller Brewing Company, 1855-2005. Milwaukee: Miller Brewing Company, 2005.

Gurda, John. The Making of “A Good Name in Industry”: A History of the Falk Corporation, 1892-1992. Milwaukee: The Falk Corporation, 1991.

Gurda, John. The Making of Milwaukee. Milwaukee: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 1999.

McCarthy, John M. Making Milwaukee Mightier: Planning and the Politics of Growth, 1910-1960. DeKalb, IL: Northern Illinois University Press, 2009.

The Allen-Bradley Story. Milwaukee, WI: The Allen-Bradley Company, 1965.

Wendel, Charles H. The Allis-Chalmers Story. Sarasota, FL: Crestline Publishing Co., 1988.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.