The exchange of goods is fundamental to city life, and the shape of commercial activity in Milwaukee reflects the geographic expansion of the city and the economic, technological, and social patterns framing the city’s development over time. Modern Milwaukee began as a series of competing settlements on the Milwaukee River and grew into a major metropolitan area encompassing over ninety-six square miles. At the same time, commercial activity spread from the riverfront to growing thoroughfares, neighborhood centers, and, by the mid-twentieth century, outlying retail destinations. The scope of commercial buildings over time included a wide variety of architectural types and functional niches. Large department stores offered fantastical displays of carefully selected merchandise. Neighborhood corner stores catered to local residents and often contributed to density with office space or residences on upper floors. Neighborhood strips and commercial streets lined with mixed-use commercial buildings typified commercial activity until the mid-twentieth century, when increasingly comprehensive centers featuring vast parking lots epitomized modern retailing. As new commercial developments emerged further from the city center, older and more central retail locations often suffered. While many neighborhood shopping areas continue to operate below their historic peak capacities, efforts to revive historic shopping areas and neighborhoods, along with a “return to the city” movement has infused new life to urban retail in the early twenty-first century. Nonetheless, constant competition leaves retailers vulnerable to a fickle market.

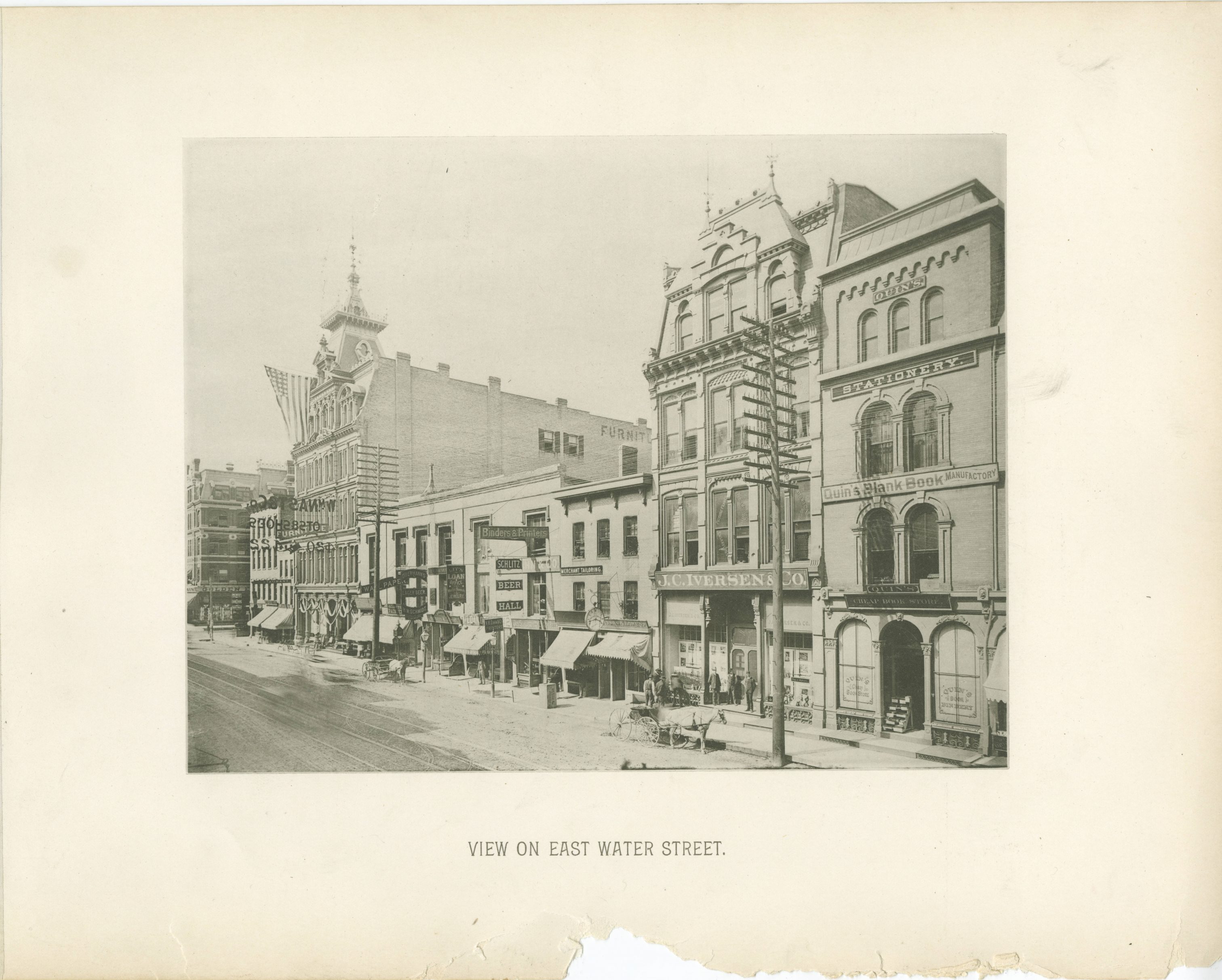

In the early nineteenth century, three competing settlements—Juneautown, Kilbourntown, and Walker’s Point—fostered their own commercial nodes. As the settlements grew, a clear commercial center formed on the east side of the river along East Water Street, with a primary node at its intersection with Wisconsin Avenue. Even in this early phase of commercial activity in the city, the retail landscape consisted primarily of specialized stores that served a limited line of items rather than general stores.[1] By 1840, commercial enterprises lined both sides of the Milwaukee River, and German immigrant entrepreneurs began remaking existing commercial structures on Third Street (west of the river) to serve the growing German community.[2] Within fifteen years, businesses lined Water Street from Juneau to Walker’s Point and passed through the Third Ward, where businesses on Water Street catered to Milwaukee’s growing Irish community.[3]

Over time, commercial activity on Wisconsin Avenue outpaced business along Water Street and the other outfits lining the river. T.A. Chapman, whose dry goods store opened in 1857 and became one of Milwaukee’s first department stores, moved to the southeast corner of N. Milwaukee Street and E. Wisconsin Avenue in 1872. The company rebuilt on site after a fire in 1884 and operated until 1981. The enterprise contributed to the East Side’s reputation for exclusive retail establishments and commercial institutions such as bank and insurance companies. The West Side, with department stores like Gimbels (1887) and the Boston Store (1900), catered to a mass market audience.[4]

Downtown was increasingly specialized as a retail and commercial district, and by the turn of the twentieth century, it was no longer primarily residential.[5] The Iron Block, built on the corner of Wisconsin and Water between 1860 and 1861, represents the larger and more ornate, mixed-use buildings that emerged during this era.[6] The cast iron building featured novel building technology; prefabricated panels offered an economical option for mimicking stone and other detailing, and it boasted a fireproofing element.

New commercial activity accompanied residential development as it pushed outwards from the original core of the city. North Third Street (now Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Drive) became the “North Side’s downtown,” lined with dry goods stores, saloons, butchers, bakeries, and other stores. Schuster’s Department Store, which opened in 1884, became an anchor of the district. For many years, area sales trailed only Wisconsin Avenue’s.[7]

Industrial activity in the Menomonee Valley isolated the neighborhoods south of that area from downtown retail competition, promoting more commercial development and a clearer hierarchy of commercial nodes.[8] For most of the nineteenth century, National Avenue was the main commercial center of Walker’s Point.[9] Victorian storefronts also lined Second and Fifth streets. 16th Street (now Cesar Chavez Drive) and 35th Street were major north-south thoroughfares serving their local communities. By 1890, businesses like Jahr’s Grocery, the Wisconsin State Bank, Patterson’s Pharmacy, and Jensen Jewelers attracted customers from across the South Side to 16th Street in the Clarke Square neighborhood.[10] By 1920, 35th Street and National Avenue was the heart of the commercial district in Silver City, boasting hardware stores, grocers, and butchers among its variety of enterprises.[11]

Mitchell Street was the commercial center of the neighborhood south of Walker’s Point, now termed the Historic South Side. Known as the “Polish Grand Avenue,” it was a counterpart to the German community’s bustling Third Street and featured larger commercial buildings than other streets in the area.[12] Lincoln Avenue developed as an important neighborhood shopping area, and merchants commonly occupied simple Victorian frame stores before upgrading to brick buildings. Some of the most interesting buildings, with shaped gables reflecting the Polish and German heritage of the storeowners, date from 1910-1920.[13] Thirteenth Street, Muskego Avenue, Forest Home Avenue, and Greenfield Avenue also provided significant commercial amenities to the area. Dense commercial streetscapes lined with two- and three-story mixed-use buildings intermixed with theaters, churches, and other facilities. Beyond such identifiable commercial streets, bakeries, butchers, saloons, and other specialty stores scattered throughout the neighborhoods.

Milwaukee’s electric streetcar service commenced in 1890, providing new impetus to residential and commercial growth. On the north side, Teutonia Avenue and Center Street joined Fond du Lac Avenue as major commercial streets. Vliet Avenue cemented its role as the main street of what is now the Midtown neighborhood. Lisbon Avenue and State Street followed as important commercial corridors northwest of downtown. Further west, 27th Street was a dense commercial street and major north-south streetcar route by 1920.[14]

Milwaukee gained new commercial areas not only by fostering new neighborhoods within city lines, but also by annexing existing residential and commercial areas. Milwaukee gained Kinnickinnic Avenue when it annexed Bay View in 1887 and the Green Bay Avenue and Third Street commercial corridors when it absorbed the Williamsburg community (now the Harambee neighborhood) in 1891. Similarly, when the city annexed Piggsville in 1925, it incorporated a variety of stores already serving the local community.[15]

The city’s first zoning regulations in 1920 restricted commercial development to main arterials, formalizing the concentration of commercial activity along major thoroughfares and streetcar routes.[16] Linear commercial corridors became standard and were reinforced by growing automobile use. For instance, the Sherman Park neighborhood developed within the context of new zoning regulations, fostering commercial corridors along North Avenue, Center Street, Burleigh Street, Fond du Lac Avenue, and Lisbon Avenue.

While neighborhood retail initially catered to daily conveniences and served an auxiliary role to the primary retail center downtown, it proved more independent by the late nineteenth century. As people lived and worked further from downtown, neighborhood commercial areas developed a wider range of goods and services. Several areas, like Upper Third Street, North Avenue, and Mitchell Street, developed into regional centers, serving not only the immediate neighborhoods but also attracting shoppers from further distances. Sears constructed a building on the corner of North Avenue, Fond du Lac Avenue, and 21st Street in 1927. The building anchored the area and was built as a sister store to a location on Mitchell Street. Both stores embodied the growing clout of neighborhood shopping districts, as department stores located branches in important commercial districts throughout the city.[17]

The consistent growth of commercial activity outwards from the center city slowed in the 1930s and 1940s, as the Great Depression constricted funds for new investment and World War II forced the rationing of building materials and some retail items. Department stores remained in business by cutting overhead costs and promoting sales and activities. In 1938, Schuster’s introduced a form of credit to assist struggling patrons.[18]

While commercial activity in Milwaukee followed residential patterns into previously undeveloped land prior to World War II, the postwar era ushered in an unprecedented speed and scale of outlying commercial development. Between 1947 and 1970, almost thirty new shopping centers, including plazas, opened in the Milwaukee region.[19] While some shopping centers primarily served new residential areas, others competed directly with historical commercial streets in city neighborhoods. In sharp contrast to commercial streets comprised of individual enterprises pursuing their own wellbeing, shopping centers embodied new, scientific theories of business decision-making. Data and formulas determined ideal locations and tenant combinations, while centralized management and planning provided wholesale control over shopping environments.

Four planned shopping centers opened in the 1950s, surrounding the city with modern retail environments. Southgate Mall, a quintessential postwar shopping center, opened in 1951. Located on Highway 41 between Oklahoma Avenue and Loomis Road, the mall catered to growing suburban development to the south and west and older neighborhoods, as well as city dwellers. Southgate Mall consisted of twenty stores arranged on a central covered walkway and featured ample parking. The novelty of the mall made it an immediate success, attracting shoppers from across the city. As other malls opened through the decade, however, Southgate responded with expansions and well-known tenants, including Gimbels department store, which opened a Southgate branch in 1954. By 1956, the mall boasted 500,000 square feet, more than four and a half times its original 105,000 square feet.[20]

While Southgate proved the potential success of planned shopping malls on the south side, Bayshore Shopping Center opened at the juncture of Port Washington Road and Silver Spring Avenue in Glendale in 1954. After its lackluster opening, analysts identified the lack of an anchor department store as a problem. A Minneapolis-based company purchased the center in 1956, immediately initiating renovations and negotiating terms with the Boston Store, which opened a Bayshore branch in 1958.

Capitol Court opened in 1956 on the northwest side, at Capitol Drive and 60th Street. Learning from Southgate and Bayshore, its developers included three anchor department stores—Schuster’s, T. A. Chapman’s, and J. C. Penney—in the original plan. The shopping center boasted partially covered walkways. Over the next two decades it added enough properties to reach 600,000 square feet by the mid-1970s.[21]

Mayfair, Milwaukee’s first “inverted mall,” opened in 1958 at Highway 100 and North Avenue. Rather than facing the surrounding parking lot, the stores faced inwards.[22] The mall featured 1,275,000 square feet of retail space and parking for 8,000 cars. Marshall Field & Co. and Gimbels represented the higher end retailers in the mall.

In addition to the four largest planned shopping centers that opened during the 1950s, others filled smaller geographic niches. Fifteen community centers—characterized by a unified architectural design—opened during the decade. Some represented increasing retail specialization with names, like Westwood Center, Shoppers Fair, and Packard Plaza, while others were identified by intersection (such as Silver Spring and 60th Street, W. North Ave and N. 89th Street, and 92nd St. and Lisbon Ave).[23] Commercial development carried momentum over the next two decades as new malls opened, older malls were renovated, and shiny commercial places embodied an unrestrained optimism in consumer spending. Point Loomis opened in 1960 at Loomis Road and 27th Street, immediately south of Southgate Mall, and posed direct competition to that shopping center. Brookfield Square, the Milwaukee area’s first fully enclosed mall, opened in 1967.

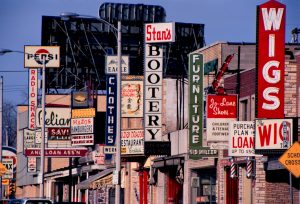

Back in city neighborhoods, local retailers felt the negative impact of unrestrained commercial development in the growing suburbs. As the frontier of new commercial spaces pushed outwards, increasing competition and declining local consumer bases compromised neighborhood retail areas that developed along streetcar lines and pedestrian-oriented communities. Between 1955 and 1960, patronage declined in downtown and on Upper Third Street, 12th and Vliet, 21st and North Avenue, and Mitchell Street, while Southgate, Bayshore, West Allis, Capitol Court, and Mayfair enjoyed gains.[24] Aggressive expressway development further undermined neighborhood commercial areas; the same freeways that provided easy automobile access to outlying commercial centers literally ripped apart the fabric of neighborhood retail streets. For instance, the construction of I-43 included widening Walnut Street, a devastating blow to the primary commercial street in Bronzeville.[25]

By the mid-1960s, city officials recognized the mounting challenges that suburban shopping centers posed to established city neighborhood retail areas. In 1967, several aldermen called for a study focused on four commercial districts across the city.[26] While acknowledging the “interference” of existing and proposed parkways and newer shopping centers on neighborhood shopping areas, the report left the onus on local retailers to entice back customers. It recommended that business owners revamp their storefronts, offer more parking, or even redevelop street sections into shopping complexes or special destinations. The report cast North Green Bay Avenue as obsolete due to its proximity to Bayshore, Capitol Court, and downtown: “This is probably a shopping area that could be eliminated.”[27] While initiated with good intentions, the report did little to help neighborhood commercial centers, which continued to suffer.[28]

Despite a professed concern for city retail, officials equated new development with economic growth and commercial development seemed inevitable. The problems of the city remained out of sight and out of mind to suburban developers. Several new malls opened in the 1970s and 1980s, and changing ownership and large-scale renovations characterized activity in existing shopping centers. Southridge Mall opened in 1970 and Northridge Mall followed two years later. In 1971 owners enclosed Southgate Mall, and Capitol Court underwent the same modernizing transformation in 1977. During this period, malls became major entertainment hubs, offering movie theaters, food courts, skating rinks, and special events. In 1975 alone, Brookfield Square boasted 190 special events.[29]

In addition to these larger malls, the city witnessed a brief trend of construction of small shopping centers. For instance, in 1976, Prospect Mall opened in a former automobile showroom on the East Side. The following year, First City Resources, a real estate firm from Illinois, purchased Prospect Mall and three other small malls in the region: Pilgrim Village, Bradley Village, and River Bend.[30] A subsidiarity of the Chicago-based JMB Realty Corporation purchased Northridge and Southridge Malls in 1988 and renovated them later that year.[31] Indeed, other out-of-town companies purchased Milwaukee malls as part of real estate portfolios stretching across the country. The rise of strip malls also countered the trend of building large enclosed malls. Between 1983 and 1988, developers built over two million square feet of strip mall retail space in Brookfield, Brown Deer, and Greenfield, near existing shopping centers.[32]

Not to be outdone, downtown interests responded to new and renovated suburban centers with Grand Avenue Mall, which opened in 1982. While the enterprise symbolized a victory of investment in the center city, it also represented a defeat in that it replicated suburban malls. The City hired the Rouse Company, known nationally for pioneering the “festival marketplace,” a new brand of commercial development that merged entertainment into the shopping experience.[33] The development refaced several nineteenth-century buildings, including the historic Plankinton Arcade on Grand Avenue as part of broader civic redevelopment plan. Like so many other shopping centers, it met fleeting success. Marshall Field and Company replaced Gimbels as the anchor department store in 1986, but it closed in 1997. In 2002, T.J. Maxx and Linens ‘n Things opened as part of an effort to revive the mall with popular chain stores. After changing ownership several times, including at an auction in 2014, the renovation plans unveiled in April 2016 re-imagined the shopping center as a downtown attraction and community gathering space with retail, collaborative office space, and an urban marketplace.[34]

Many of the same patterns of redevelopment and competition characterize commercial Milwaukee in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. The advent of “big-box” stores and internet shopping comprise new challenges to brick-and-mortar retail stores. As before, there are winners and losers in the constant remaking of commercial places. Southgate, Capitol Court, and Northridge closed between 1999 and 2003. Goldmann’s, a dry goods store turned department store and Mitchell Street institution, closed in 2007 after more than 110 years of operation.[35] By contrast, Kohl’s, which began as a grocery and developed into department store in 1962, remains successfully on the map; the business is based in Menomonee Falls and operates over 1,100 stores in forty-nine states.[36] A major renovation of Bayshore transformed the mall into a “Town Center,” following the newest trend of mall themes. The Milwaukee Public Market opened in 2005, echoing the past of vendors in the Third Ward, and symbolizing the revitalization of the area into high-end condominiums and shops. Other city neighborhoods continue to promote local shopping and highlight retail streets as central to neighborhood identity.

Footnotes [+]

- ^ Michael P. Conzen and Kathleen Neils Conzen, “Geographical Structure in Nineteenth-Century Urban Retailing: Milwaukee, 1836-90,” Journal of Historical Geography 5, no. 1 (1979): 52.

- ^ Conzen and Conzen, “Geographical Structure in Nineteenth-Century Urban Retailing,” 53.

- ^ John Gurda, Milwaukee: City of Neighborhoods (Milwaukee: Historic Milwaukee, Inc., 2015), 20.

- ^ Gurda, Milwaukee, 9.

- ^ Gurda, Milwaukee, 7.

- ^ Richard W.E. Perrin, Milwaukee Landmarks: An Architectural Heritage, 1850-1950 (Milwaukee: Milwaukee Public Museum, 1968), 76; Megan E. Daniels, Milwaukee’s Early Architecture (Charleston: Arcadia Publishing, 2010), 20. Daniels notes some of the unintended consequences and costs of cast iron facades, such as rusting.

- ^ Gurda, Milwaukee, 178-79.

- ^ Conzen and Conzen, “Geographical Structure in Nineteenth-Century Urban Retailing,” 58.

- ^ Gurda, Milwaukee, 347.

- ^ Gurda, Milwaukee, 358.

- ^ Gurda, Milwaukee, 372.

- ^ Gurda, Milwaukee, 381.

- ^ Milwaukee Ethnic Commercial and Public Buildings Tour: The Rich Heritage of Immigrant Architecture (Milwaukee: Department of City Development, 1994), 51. See also Christel T. Maass and Roman B.J. Kwasniewski, Illuminating the Particular (Madison, WI: Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 2003).

- ^ Gurda, Milwaukee, 66.

- ^ Gurda, Milwaukee, 88.

- ^ Gurda, Milwaukee, 154.

- ^ For more on neighborhood department stores generally, see Richard Longstreth, “The Neighborhood Shopping Center in Washington, D. C., 1930-1941,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 51, no.1 (1992): 5-34.

- ^ Christopher Chan, “Mass Consumption in Milwaukee: 1920-1970” (Ph.D. diss., Marquette University, 2013), 280-81.

- ^ Metropolitan Milwaukee Association of Commerce, Milwaukee Shopping Centers, 1973-74, (Milwaukee: Urban Research and Development Division Metropolitan Milwaukee Association of Commerce, 1974).

- ^ “Lost Milwaukee: Southgate,” Milwaukee Murmur, last accessed April 21, 2018; John Gurda, “In 1951, Southgate Changed Shopping,” reprinted from the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, December 5, 1999, last accessed April 21, 2018.

- ^ Bayshore Town Center, ULI Development Case Studies (July-September 2009), https://casestudies.uli.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/98/2015/12/C039011.pdf, p. 3, last accessed April 21, 2018.

- ^ Donald George Leeseberg, “Retail Trade Trends in Metropolitan Milwaukee: 1948-1959” (D.B.A. diss., University of Washington, 1961), 219.

- ^ Leeseberg, “Retail Trade Trends in Metropolitan Milwaukee,”181, 182.

- ^ Ralph E. Brownlee, “Neighborhood Shopping Area Study” (Milwaukee: City of Milwaukee, 1967), 14.

- ^ Gurda, Milwaukee, 201.

- ^ The study defined the following four target areas: 1) West Fond du Lac between 18th and North 29th Street; 2) North Green Bay Avenue between West Burleigh Street and West Keefe Avenue; 3) South Kinnickinnic Avenue between East Becher and East Morgan; 4) South Muskego from West Greenfield to West Lincoln, South 16th Street from West Pierce Street to West Greenfield Ave.

- ^ Brownlee, “Neighborhood Shopping Area Study,” 61.

- ^ For instance, see Leslie Johnson Clevert, “Teutonia Area Dying, Merchants Say,” Milwaukee Journal, July 1, 1976.

- ^ Anthony P. Carideo and Georgia Pabst, “Shopping Centers Remold the Landscape,” Milwaukee Journal January 25, 1976.

- ^ Tom Tolan, “Little Shopping Malls Worried,” Milwaukee Journal, December 30, 1977. Prospect Mall closed in 2006.

- ^ Erik Gunn, “Northridge, Southridge Sold,” Milwaukee Sentinel, January 20, 1988.

- ^ Tina Daniell, “Retailing Gets Makeover: Strip Centers Spring Up, Challenging Malls,” Milwaukee Journal, October 23, 1988.

- ^ For more on James Rouse and the festival marketplace, see Nicholas Dagen Bloom, Merchant of Illusion: James Rouse, America’s Salesman of the Businessman’s Utopia (Columbus, OH: The Ohio State University Press, 2004).

- ^ Sean Ryan, “Grand Avenue Owners Unveil Plans to Transform Downtown Mall,” Milwaukee Business Journal, April 25, 2016.

- ^ Chan, “Mass Consumption in Milwaukee,” 295.

- ^ “Kohl’s Corporation Reports First Quarter Financial Results,” Kohl’s Corporation website, May 12, 2016.

For Further Reading

Chan, Christopher. “Mass Consumption in Milwaukee: 1920-1970.” Ph.D. diss., Marquette University, 2013.

Conzen, Michael P., and Kathleen Neils Conzen. “Geographical Structure in Nineteenth-Century Urban Retailing: Milwaukee, 1836-90.” Journal of Historical Geography 5, no. 1 (1979): 45-66.

Gurda, John. Milwaukee: City of Neighborhoods. Milwaukee: Historic Milwaukee, Inc., 2015.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.