Like all urban areas, early Milwaukee faced many issues when it came to burying the dead. There were concerns with sanitation and the threat of disease, the competition for space with businesses and housing, and the need to properly memorialize those who died.[1]

Milwaukee’s early cemeteries had neither the permanence nor the grandeur of its later cemeteries. Native American burial grounds were often plowed over or built on as European Americans settled the area. Milwaukee’s new residents established six cemeteries in the late 1830s and 1840s, but by the end of the 1850s most were either displaced or threatened by development. Among the early cemeteries were Milwaukee Cemetery at Sixteenth and Elizabeth Street (National Avenue); Gruenhagen’s cemetery at Thirteenth and Chestnut (Juneau Avenue) for German Protestants; the Catholic cemetery at Twenty-Second and Spring (Wisconsin Avenue); the Jewish cemetery at Fifteenth and Teutonia; a cemetery on the East Side at Lyon and Cass; and another on the West Side at Ninth and Spring (Wisconsin Avenue).[2]

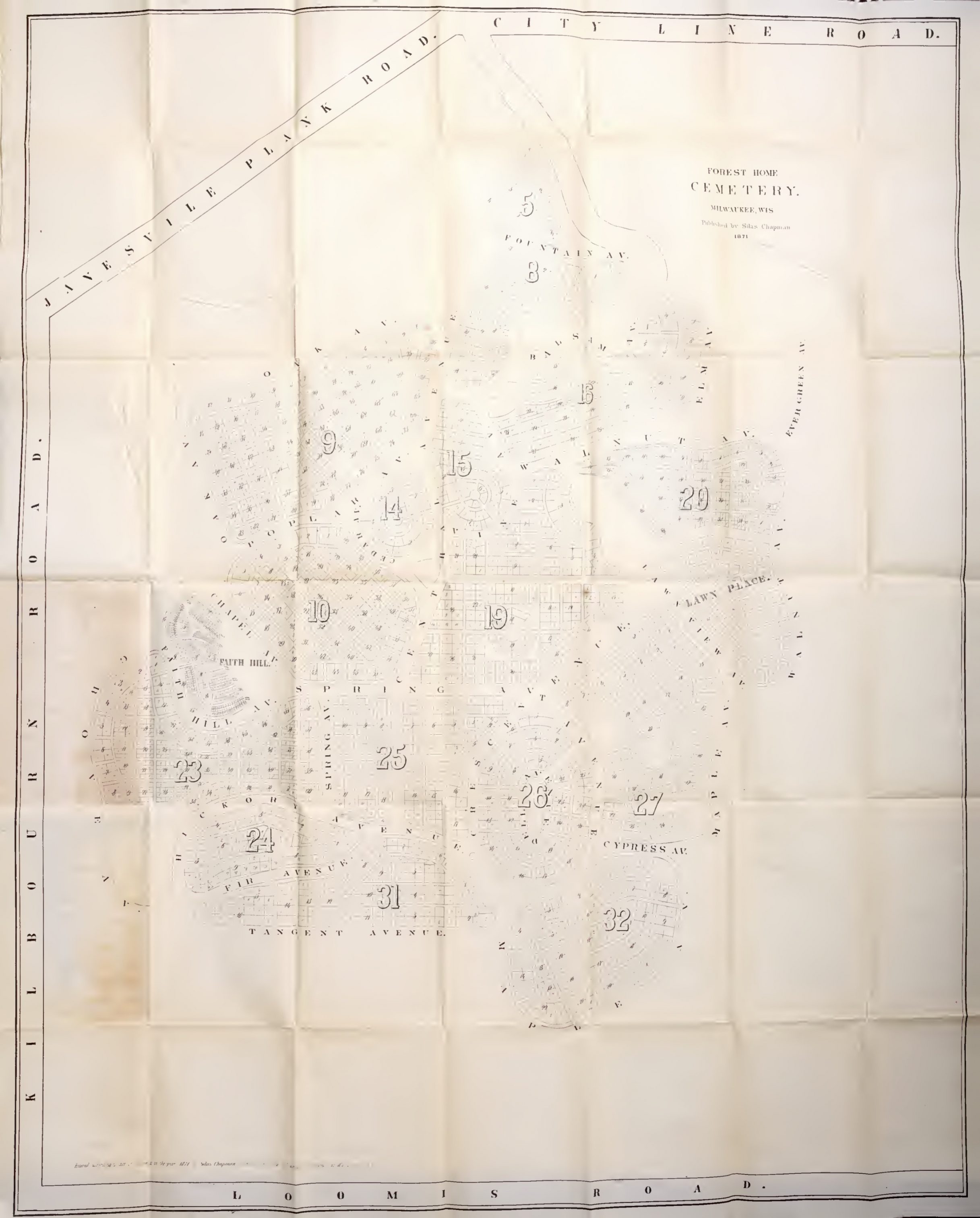

Recognizing a need for a more permanent resting spot, members of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church established Forest Home Cemetery in 1850. Based on Boston’s Mount Auburn, the first of the “garden” cemeteries, Forest Home quickly became Milwaukee’s largest, best maintained, and most prestigious cemetery.[3] Garden, or rural, cemeteries used elaborate landscaping to create a park-like setting. Cemeteries also often acted as outdoor gathering spots, especially before cities developed systems of parks. Increase Lapham, a Wisconsin scholar and scientist, designed the grounds for Forest Home with curved pathways, copious trees, and picturesque landscaping.[4] Many of the bodies in the earliest cemeteries were moved to Forest Home as they became threatened by decay and urban development. Other large, garden-style cemeteries were developed in the greater Milwaukee area in the ensuing years.

Conflict over the use of space was a consistent theme with Milwaukee’s early cemeteries, as many people wanted to see the land used for businesses or housing. Often the bodies in small cemeteries were relocated to areas further from the city center so that the former burial ground could be put to other purposes. Despite these changes, a number of early cemeteries still exist; many are barely recognizable, but some are still maintained or even in use. Examples of early cemeteries still in use include St. Michael’s Catholic Cemetery (in Brown Deer),[5] which dates to the late 1840s[6]; West Granville Cemetery (in the City of Milwaukee’s Granville neighborhood), where the oldest burial dates to the early 1840s; and St. Catherine of Alexandria (at 76th and Good Hope Road), which dates to the 1850s.[7]

In addition to Forest Home, there are number of other notable cemeteries in the greater Milwaukee area, including Wood National Cemetery, which was established in 1871 as Soldiers’ Home Cemetery for soldiers who died while under care at the National Soldiers’ Home.[8] Cavalry Cemetery is the oldest Catholic cemetery in Milwaukee and was designated a Milwaukee landmark in 1981.[9] Wisconsin Memorial Park was established in 1929 and is the largest cemetery in Waukesha County, both in size and number of burials.[10] Some early Ozaukee County cemeteries like St. Mary’s in Port Washington (established 1854) and St. Joseph’s in Grafton (established 1855) are still in use today. The cemetery is owned and operated by the West Bend Cemetery Association, which organized in 1857 and soon after established Union Cemetery, which still exists.[11]

It is also important to note that not all burials are in large cemeteries. Throughout the generations there have been hundreds of small and medium cemeteries in the greater Milwaukee area, some of which exist today. However, many of these smaller cemeteries face an uncertain future as the age-old conflict over land use continues. These conflicts are exacerbated as the population continues to increase, putting pressure on urban areas to determine how to accommodate the need for burial places. In addition there is a robust dialogue as to the environmental propriety of burying the dead. Organizations such as the Green Burial Council argue that the old methods for embalming and burial damage the environment and that above-ground internment is a wasteful use of materials. Advocates for green burial make the case that new methods should be used; many cemeteries are offering green burial options today.[12] For example, within Forest Home Cemetery, the Prairie Rest area is reserved for green burial.[13] In addition to conservation burial, there is a movement to incorporate cemeteries into a community’s green infrastructure by balancing the need for burial spaces with their potential for ecological diversity and engagement with the outdoors.[14] All of these pressures and changing approaches suggest that a new phase in how Milwaukeeans bury the dead could be on the horizon.

Footnotes [+]

- ^ For more on mid-nineteenth century concerns with urban graveyards, as well as how burial sites have changed in the United States, see David Charles Sloane’s The Last Great Necessity: Cemeteries in American History (Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991).

- ^ Former Burial Places, Milwaukee Sentinel, July 4, 1894, Cemeteries Collection, Mss 1744, Milwaukee County Historical Society.

- ^ For more on Forest Home Cemetery see John Gurda’s Silent City: A History of Forest Home Cemetery (Milwaukee: Forest Home Cemetery, 2000).

- ^ Landscape Research, City of Milwaukee, Dept. of City Development, Built in Milwaukee: An Architectural View of the City (Milwaukee, WI: City of Milwaukee, 1983), 115, 117.

- ^ “St. Michael’s Cemetery,” Milwaukee County Online Genealogy and Family History Library, last accessed September 14, 2016.

- ^ Elizabeth Herzfeld, Old Cemetery Burials of Milwaukee County, Wisconsin, vol. I (Bowie, MD: Heritage Books, 1997), vii.

- ^ Elizabeth Herzfeld, Old Cemetery Burials of Milwaukee County, Wisconsin, vol. II (Bowie, MD: Heritage Books, 2001), ix; St. Catherine of Alexandria Catholic Church, http://www.saintcatherinealexandria.org/generalinfo/history.htm, accessed April 12, 2016.

- ^ National Cemetery Administration, accessed April 12, 2016.

- ^ Milwaukee Historic Preservation Commission, Historic Designation Study Report, accessed April 10,2016.

- ^ Waukesha County Cemeteries, Ellen M. Rohr, accessed April 10, 2016.

- ^ Washington County Memorial Park, http://www.washingtoncountymemorialpark.com/History.htm, accessed April 12, 2016.

- ^ Alexandra Harker, “Landscapes of the Dead: An Argument for Conservation Burial,” accessed August 17, 2016http://ced.berkeley.edu/bpj/2012/09/landscapes-of-the-dead-an-argument-for-conservation-burial/.

- ^ Rachael Glaszcz and Courtny Gerrish, “Prairie Rest Cemetery Offers Green Burials,” Today’s TMJ4, last accessed February 9, 2018.

- ^ Carlton Basmajian and Christopher Coutts, “Planning for the Disposal of the Dead,” Journal of the American Planning Association, 76, no. 3: 305-317. Accessed August 17, 2016.

For Further Reading

Grafelman, Katherine. “Green Burial: Insights from Industry Practitioners and Popular Media.” MS thesis, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2010.

Gurda, John. Silent City: A History of Forest Home Cemetery. Milwaukee: Forest Home Cemetery, 2000.

Herzfeld, Elizabeth. Old Cemetery Burials of Milwaukee County, Wisconsin. 2 vols. Bowie, MD: Heritage Books, 1997 and 2001.

Sloane, David Charles. The Last Great Necessity: Cemeteries in American History. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.