Even though it is a brutally cold December day in the city, the Milwaukee Public Market—an indoor collection of close to twenty food and drink vendors that opened in 2005—is packed. It is lunchtime, and men and women who work downtown are taking advantage of the market’s proximity to the office towers that they will rush back to after a quick meal. A collection of college students order coffee from Anodyne, a Milwaukee-based coffee roaster serving the city since 1999. A mother tries to soothe her two rambunctious children with sweets from Kehr’s Candies, a candy manufacturer that has been turning out such treats from its small facility on the city’s North West side since 1930. And more and more people are venturing out to the Third Ward neighborhood to enjoy the market: customer visits rose 11.6 percent, to 1.4 million in 2015 from 1.2 million in 2014. Sales by the market’s vendors reached $14.4 million in 2015, up close to 20 percent from the previous year’s total sales.[1]

On the one hand, it is easy to place such growth in the context of the revival of the neighborhood that houses the Milwaukee Public Market. Young professionals have flocked to the Third Ward, as expensive condominium projects come to replace the warehouse spaces that previously called this neighborhood home. Like Pike Place in Seattle and Eastern Market in Washington, D.C., the Milwaukee Public Market features an assortment of products—from artisanal cheeses to high-end liquors—meant to appeal to the upper-class shopper.

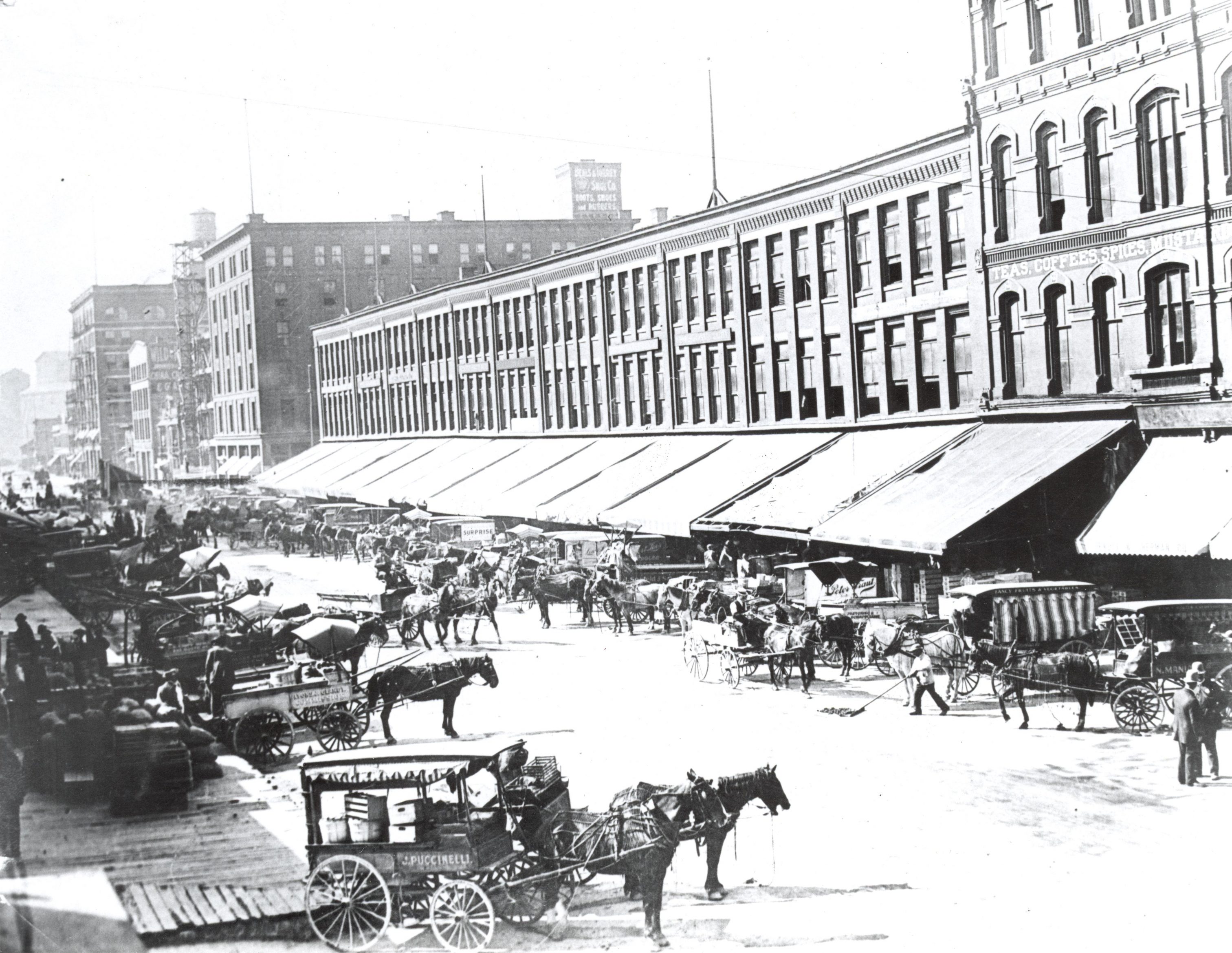

Yet the presence of such small-scale, local producers as Anodyne and Kehr’s Candies suggests that there is more to this story than simple gastronomic gentrification. The Milwaukee Public Market itself sits across the street from historic Commission Row, a site that, at the turn of the twentieth century, served as the focal point for the bustling trade of fresh fruits and vegetables for the growing city. The activity associated with Commission Row stoked further food-related development: by 1915, the predominantly Italian neighborhood featured 29 saloons, 45 groceries, two spaghetti factories, and a myriad of liquor distributors and dry goods businesses. In real ways, the commitment to local businesses on display at the Milwaukee Public Market is just the latest evolutionary stage of the neighborhood’s role as food capital of the city.[2]

The story and setting of the Milwaukee Public Market suggests just how important food has been, and continues to be, to the economic development of the city—a reality often overlooked by historians and laypersons alike. After all, Milwaukee was known as the “Machine Shop of the World” throughout much of its history, as firms such as Allis-Chalmers and Pawling and Harnischfeger turned out large-scale industrial equipment for customers across the globe. And when this era came to a close, city and private-sector leaders alike struggled to embrace a service-oriented economy that would help address the traumas associated with this deindustrialization process. Yes, Milwaukee remained known as a city devoted to its beer throughout such intense economic dislocations, but even this characteristic came to be questioned. By the end of the twentieth century, such celebrated breweries as Pabst and Schlitz had shuttered their Milwaukee plants.

A closer look at the history of food in Milwaukee allows us to see this narrative of declension in a new light and may allow us to even challenge it. If Milwaukee’s growth was centered on industrial manufacturing for much of its history, such growth was also fueled by the production of food and food-related goods and services. On the one hand, there is little doubt that such production led to increased economic development in Milwaukee. Yet, perhaps more importantly, food also led to the development of such non-monetary attributes as community, ethnic solidarity and acculturation, and civic identity. Thankfully, such histories are coming to inform the city as it struggles to redefine itself in the early twenty-first century. From the floor of the Milwaukee Public Market to the tables of the city’s finest farm-to-table restaurants (and the fields and greenhouses of the urban farms that supply such restaurants), Milwaukee and its residents are seeing that food can help fuel a city’s rebirth.

The Beginnings

Because of its closeness to the fertile soil of such nearby counties as Ozaukee, Waukesha, Washington, and Walworth counties—and because of its proximity to Lake Michigan—the city of Milwaukee quickly became a center of exchange for an assortment of food related products. From the 1830s through the Civil War, Milwaukee became, for example, the largest shipper of wheat in the world. In downtown Milwaukee, the opulent Grain Exchange helped set the price for such farm commodities around the world.

Not surprisingly, Milwaukee also soon became a center for the processing of food crops; flour was the first agricultural product to be processed large-scale in the city. By 1870, local output of flour had reached 1.2 million barrels; only St. Louis milled more flour. Barley and hops grown on southeastern Wisconsin farms went to the city’s brewing industry—to be turned into the product that made Milwaukee famous: beer. There were twenty-six breweries scattered throughout the city by 1856. By 1874, Pabst was the nation’s largest brewery.[3]

Towards the end of the nineteenth century the city had also become a national leader in the raising of hogs. By 1872, Milwaukee ranked fourth among American cities in the number of hogs butchered annually, with 310,913. A vast infrastructure of meat-processing plants sprung up across the city, producing a variety of food products. At the same time, the hides of these slaughtered animals went to the tanneries that dotted the city’s landscape. By 1890, the city had become the largest producer of plain tanned leather in the country.[4]

But the city also retained a distinctly agricultural flavor, as farms continued to dot Milwaukee’s increasingly industrial landscape. Recent immigrants to Milwaukee brought with them the experiences of farming in the Old World. Not surprisingly, such individuals took to working the soil in their new home as well. On the South Side, farmers such as Henry Griswold Comstock took advantage of such expertise, and the fact that these immigrants desperately needed jobs. In 1891, Comstock began raising celery on a tract of land bounded by W. Lapham Street, W. Burnham Street, S. Layton Blvd., and S. 31st Street. Comstock’s celery-growing business grew quickly: his crop was worth $50,000 a year by 1900, with half of that being profit. The son of an original Milwaukee European pioneer, Comstock made it a point to hire those who had recently come to the United States. More specifically, in the words of one Milwaukee journalist, Comstock liked to employ “recently arrived Polish immigrants in an agricultural atmosphere reminiscent of their old country.” By the time of his death in 1937, Comstock was growing on 250 acres of land stretching from W. Forest Home Avenue to W. Orchard Street and from S. 32nd to S. 37th Streets.[5]

A Market-Based Economy

Such farmers needed ways to get their products into the hands—and mouths—of consumers. In the early 1880s, a petition was presented to the Milwaukee Common Council requesting that the city organize and operate the space previously known as “Haymarket Square” as a public market. The space, located at 5th Street and Vliet Street, had previously been the center of a vibrant hay trade in Milwaukee. In 1884 the Common Council directed the city attorney to draw up an ordinance legalizing rents for the use of the public market grounds.[6]

Despite such ambitious plans, it was not until 1908 that what came to be known as “Central Market” became a hub for the sale of fresh produce. The market area was expanded in 1912 when the city, through condemnation procedure and direct purchase, acquired adjacent properties. At the same time, the market superintendent, at the request of the mayor, visited nearby farmers to convince them to use the city-owned facilities at Central Market. The next year, city ordinances were enacted for the administration and regulation of the market, and by 1916 the drive was a success—all available space was fully utilized.[7]

By that time another such space, Commission Row, had taken root in the city’s Third Ward neighborhood. Prior to the tragic October 1892 fire, the Third Ward had been the home of the city’s Irish population. Yet the sheer devastation of the fire—close to 450 buildings destroyed and more than 1,900 people left homeless—pushed the Irish community to look for homes elsewhere throughout the city. As the slow redevelopment process began, more and more recent Italian immigrants came to see the value in the urban blank slate the fire created. By 1894, Broadway Street was home to Commission Row, a bustling produce marketplace where buyer and seller met in noisy exchange. And exchange they did. By 1946, about 13,377 carloads of fresh fruits and vegetables, with an estimated value of $24,078,600, were sold in Milwaukee, with the majority of these sales taking place at such marketplaces as Commission Row and Central Market.[8]

By 1940 the city of Milwaukee, in addition to the Central Market, featured four other public markets: the Fond du Lac Avenue market; the Center Street market (N. 30th Street and W. Center Street); the East North Avenue market (E. North Avenue and E. Kenilworth Place); and the National Avenue market (S. 7th Street and W. National Avenue). Stalls at the non-Central markets could be rented for $20 a season. At the Central Market, stalls rented for $15 to $25 a year, depending on the placement of the stall. Such rates were well worth it to the vendors: collectively, these markets moved more than 50,000 tons of vegetables, fruit, poultry, eggs, and flowers each growing season. The vendors helped create a truly local economy of food products, one that stressed regional crops that grew well in both Wisconsin soil and weather.[9]

Individual consumers as well as wholesale buyers appreciated these sites for their selection of fresh goods and the convenience of being able to purchase them at one central site. But there was more to their appeal than mere economics. “These markets are pleasant places,” observed one 1940 customer, “retaining even in the midst of the city’s bustle an atmosphere of a more quiet and leisurely way of life.” In fact, these markets helped to contribute to Milwaukee’s identity as a city where green space was to be valued, an identity initially cultivated by the city’s early Socialist politicians and planners. Here one could see “a bit of the great outdoors in all of its green profusion transplanted to gray concrete.”[10]

These markets had become hubs for the sale of produce, both wholesale and individual, by the mid-twentieth century. But as farming practices, as well as the city’s population base, continued to change these markets came to face significant problems. Moreover, large chain supermarkets soon came to influence the buying habits of city shoppers. In post-World War II Milwaukee, more and more consumers came to favor the convenience of the mega-store over the intimacy of the small city markets. By 1967, the city boasted forty A&P supermarkets, twenty-nine Kohl’s, ten Red Owls, twenty-three National Food supermarkets, and twenty-one Sentry’s supermarkets. Throughout the next decade the majority of the city’s green markets would close, bookended by the closure of the Central Market in 1971 and the closure of the Center Street market in 1980. [11]

For many observers, the shuttering of the Center Street market reflected the city’s changing population base. The Center Street market had been a crucial part of the European immigrant existence throughout its long history. Now that such individuals were fleeing to the suburbs or dying off, there were no longer any customers to sustain such time-honored traditions. Upon the announcement of its impending closure, The Milwaukee Journal ran a piece with the title “The Center St. Crowd,” cataloging recollections of old-timers—all white—on the market. The article captured the sense of the city’s remarkable changes through testimony by those such as Margaret Palmer, who told the paper that “I’ve been coming here since I was a child.” Watching the vendors close up for the last time, Palmer admitted that “I’m upset. My parents grew up near here and when my daughters come to visit, we all come to the market.” Palmer liked the products offered at the market, but there was something else she would miss more than fresh produce. “It’s not that it’s a place of beauty,” concluded Palmer, “it’s a habit. And I just think that in this town with its traditions, its Polish and German culture, that this is something we should maintain.”[12]

Yet in June 1981 the city opened the Fondy Market, located near the intersection of 21st Street and Fond du Lac and North Avenues—approximately three-quarters of a mile from the recently deceased Center Street Market. This municipal-run space attempted to modernize the market for the late twentieth century. A Milwaukee Journal piece on the overall plan for the site stressed the design’s “covered stalls, on-site parking, colorful banners, and pedestrian amenities.” Milwaukee Mayor Henry Maier, at the ribbon-cutting ceremony for the new facility, noted that “We are taking a giant step toward restoring the Fondy business area to its place of prominence.”[13]

As Maier’s comments suggest, there was the hope that the market would help catalyze urban redevelopment and lead to a sort of economic rebirth in a neighborhood affected by population change and economic disinvestment. The Polish and German immigrants that Margaret Palmer remembered had been replaced by African Americans, as more and more of these migrants made the move from the rural South to the urban North during the second half of the twentieth century. At the same time, there was a genuine push to have this new market, and what it sold, speak to those that now called this community home. An October 1988 advertisement for the market, for example, highlighted the fact that they carried sweet corn, sweet potatoes, and okra, or food products that historically played significant roles in the cooking and eating habits of African Americans—and were not easily found in a northern city like Milwaukee. Based upon its willingness to speaking to a changing Milwaukee, the Fondy Market remains an important city asset in the twenty-first century.[14]

Come Together: Milwaukee and the Sociability of Food

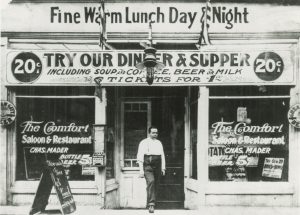

Such markets suggest the importance of food to both the economic and spatial development of Milwaukee. They also highlight how food often worked to speak to and strengthen the cultural identities of the city’s diverse residents. Such important work was also done in Milwaukee’s ethnic taverns, beer gardens, and restaurants, which, by the mid-nineteenth century, worked to create a sense of palpable community within the city’s growing German population. However, taverns such as Trayer’s inn—established in 1841—became more than just sites of sociability; they also helped recent immigrants find jobs and learn about the political parties that held sway in Milwaukee. Such establishments quickly showcased the growing economic might of the city’s burgeoning German population. In 1902, Charles Mader purchased an entire building on Plankinton Avenue and opened the Comfort, a German restaurant meant to cater to newcomers to the city. Mader soon renamed his restaurant (to “Mader’s”) and moved it to Third Street—where it still stands today.[15]

More recent waves of immigrants have also used food to acclimate to the city. On the city’s south side, post-World War II Latino immigrants transformed National Avenue, Mitchell Street, and Cesar E. Chavez Drive into sites of food production and distribution. Businesses such as the restaurant Conejito’s Place (established in 1972), Lopez Bakery (which opened its first site in 1978), and Super Mercado El Rey (1978) all provided both employment and beloved culinary products to those arriving in Milwaukee from south of the border. Other businesses provided much-needed social outlets. The Juana Diaz Tavern, for example, sponsored community softball and baseball tournaments, a dominoes league, and billiard tournaments. Such spaces have remade the physical environment of Milwaukee’s South Side community while providing the primary source of cultural identity for the city’s fastest-growing demographic.[16]

Despite such changes to the city’s population base, the twenty-first century has seen other vendors and restaurateurs returning to the regional produce—and the smaller-scale farmers that provide such products—that played such prominent roles in the city’s early markets as they attempt to speak to the contemporary climate of Milwaukee. Cooperatively-run grocery stores such as Outpost Natural Foods (which opened its first store in 1970) and the Riverwest Co-Op Grocery and Café (which opened in 2001) have led the way here, stocking their shelves with locally-grown produce. Larger, high-end grocery stores such as Whole Foods—which came to Milwaukee’s East Side neighborhood in 2006—quickly followed suit. Moreover, “farm-to-table” restaurants as Braise (which opened in 2006) feature a constantly evolving menu that highlights seasonal Wisconsin produce. Braise head chef Dave Swanson makes it a point to buy from such local farms as Growing Power, a Milwaukee-based urban farm founded by former professional basketball player Will Allen in 1993. Growing Power, like other urban farms such as Walnut Way and Alice’s Garden, sells its fresh fruits and vegetables to a myriad of restaurants, supermarkets, and specialty stores—all with the end goal of providing employment for the city’s African-American population.[17]

The work being done at Growing Power takes place miles away from the urbane setting of the Milwaukee Public Market. Yet both sites suggest that food remains a vital component of how the city continues to develop, both physically and economically. Yet perhaps most importantly, these sites highlight how food continues to inform the evolving identity of Milwaukee: urban agriculture and the locally-owned food businesses with the Milwaukee Public Market are components of marketing efforts conducted by city leaders to present a new face of the city to outside observers—and potential investors. As Milwaukee attempts to “green” its “Rust-Belt,” such stores, farms, and restaurants, and the histories that inform these efforts, have become potent symbols of a city re-imagining itself.

Footnotes [+]

- ^ Rick Romell, “Public Market Sets Record for Sales, Visits,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, January 20, 2016.

- ^ “About the Historic Third Ward,” Historic Third Ward, accessed December 10, 2015, http://www.historicthirdward.org/about/aboutthethirdward.php.

- ^ John Gurda, “Eat, Drink, and Be Prosperous: A Short History of the Food and Beverage Industry in the Milwaukee Region—The Seven Counties of Southeastern Wisconsin,” Report Commissioned by the Milwaukee 7, December 7, 2010, accessed November 20, 2015, 3.

- ^ Gurda, “Eat, Drink, and Be Prosperous,” 3.

- ^ Edward S. Kerstein, My South Side (Milwaukee, WI: Milwaukee Journal, 1976), 2; City of Milwaukee, Historic Designation Study Report, South Layton Boulevard Historic District, 900 Block through 2200 Block, S. Layton Boulevard, September 2004, accessed September 15, 2015.

- ^ Marketing and Facilities Research Branch, U.S. Department of Agriculture, in cooperation with the Department of Agricultural Economics, University of Wisconsin, “The Wholesale Produce Market at Milwaukee, Wis.,” January 1950, 4, Legislative Reference Bureau, Milwaukee City Hall, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, 1, 2, 3, 6, and 7.

- ^ U.S Department of Agriculture, “The Wholesale Produce Market at Milwaukee, Wis.,” 7.

- ^ Agricultural Experiment Station, University of Wisconsin, Madison, “Milwaukee Wholesale Fruit & Vegetable Market,” February 1948, Legislative Reference Bureau, Milwaukee City Hall, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, 1.

- ^ “Market Stalls Open for 1940,” The Milwaukee Journal, June 16, 1940.

- ^ “Market Stalls Open for 1940,” The Milwaukee Journal, June 16, 1940.

- ^ Christopher Chan, “Mass Consumption in Milwaukee: 1920-1970” (Ph.D. dissertation, Marquette University, 2013), 235 and 251.

- ^ Marilyn Gardner, “The Center St. Crowd,” The Milwaukee Journal, June 25, 1980.

- ^ “Farm Mart to Feature Amenities,” The Milwaukee Journal, December 4, 1979; “Fondy Farm Market Heralds Area Rebirth,” The Milwaukee Sentinel, June 23, 1981.

- ^ “Fondy Farmers Market,” advertisement, The Milwaukee Sentinel, October 8, 1988.

- ^ Kathleen Neils Conzen, Immigrant Milwaukee, 1836-1860: Accommodation and Community in a Frontier City (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1976), 156; Lori Fredrich, Milwaukee Food: A History of Cream City Cuisine (Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2015), 22.

- ^ Joseph A. Rodriguez and Walter Sava, Latinos in Milwaukee (Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2006), 31-35.

- ^ Fredrich, Milwaukee Food, 48-51; Will Allen with Charles Wilson, The Good Food Revolution: Growing Healthy Food, People, and Communities (New York: Penguin Group, 2012).

For Further Reading

Allen, Will, with Charles Wilson. The Good Food Revolution: Growing Healthy Food, People, and Communities. New York: Penguin Group, 2012.

Conzen, Kathleen Neils. Immigrant Milwaukee, 1836-1860: Accommodation and Community in a Frontier City. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1976.

Fredrich, Lori. Milwaukee Food: A History of Cream City Cuisine. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2015.

Rodriguez, Joseph A., and Walter Sava. Latinos in Milwaukee. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2006.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.