Italian immigrants began to come to Milwaukee, especially from Sicily, in significant numbers in the 1890s. They settled primarily in the Third Ward after the 1892 fire that devastated the ward. The community grew over the next generation, building a close-knit neighborhood and vibrant cultural presence in the city. By 1920, a few years before the United States ended its open immigration policies and thus stopped significant further immigration, some 12,000 Milwaukeeans claimed their fathers were born in Italy.

Italians had a presence in Milwaukee as early as the Civil War era, when Michael Biagi settled in the city.[1] The major growth of Italian immigration coincided with the period of severe economic difficulties in Italy, especially for the people of Southern Italy. By 1910, eight out of every ten Italian immigrants in Milwaukee had come from the southern regions of Italy, with smaller numbers of central and northern Italians, who became a presence in Bay View.[2]

The majority of Italian immigrants had worked in the fields as farmers before coming to the United States, and even those who had performed skilled labor back home found themselves taking up the unskilled laboring jobs that were available in the Third Ward and throughout Milwaukee. The majority of these jobs where in the manufacturing industry or railroads that came from the proximity to Chicago and Lake Michigan. Other Italians found work in municipal jobs for the city, many of the streets and walkways of Milwaukee were first laid by these immigrants. In 1915, 75% of Italian immigrants worked manual labor jobs like these; another 15% worked as tradesmen throughout the city, with the remaining 10% working service jobs such as barkeepers or in small businesses like peddlers or grocers.[3]

Life in Milwaukee presented new challenges for these early immigrants. Working manual labor jobs could usually earn these men around $600 a year (around $14,300 in 2017 dollars) if they were able to work year-round.[4] The harsh Wisconsin winters caused work to grind to a halt for four to five months a year so they would often end up only bringing home around $300-$400 a year, or return to Italy for the winter. To supplement this income, Italian women immigrants usually performed light work of managing grocers or shopkeeping in addition to keeping house.[5]

The difficulties of adjusting to life in Milwaukee did not prevent the Italian community from growing and prospering. This growing community put down roots in the Third Ward where they stayed from the 1890s until the 1960s, while also expanding north into what was then the First Ward, around Brady Street. The center of community life in the Third Ward was the Blessed Virgin of Pompeii Catholic Church. Called the “little pink church,” the Blessed Virgin became a focal point for the neighborhood. It hosted religious services, weddings and funerals, and the many “festas” that characterized community life. Italian children almost always attended Milwaukee Public Schools rather than in the Catholic schools in the area.[6]

These communal bonds were forged in the hardship that the early Italians endured while carving out a life for themselves in the Third Ward. Families from Southern Italy were used to a far warmer climate than the frigid winters of Wisconsin and took some time to adapt their domestic habits to local weather. A 1915 survey of Milwaukee noticed that “in the majority of cases of the Italian workmen in Milwaukee; a wood or coal stove in the kitchen is the only source of warmth.”[7] Observers at the time believed that lack of familiarity with the cold climate combined with the cultural predilection of Italians for not staying indoors to socialize led to a wealth of illness such as tuberculosis and pneumonia within the Third Ward.[8]

Housing conditions in the Third Ward proved another challenge as landlords sought to take advantage of the immigrants by overcharging rent and often placing several families into spaces meant for much smaller households. Mario Carini, author of Milwaukee’s Italians, described the difficulties: “The housing was a big issue….We used to move around a lot. But it used to always be within the Third Ward. We’d go from corner to corner or block to block.”[9]

Despite the difficulties that came with life in the Third Ward, the Italian community concentrated in the area and formed Milwaukee’s little Italy in the neighborhood, until much of it, including the Blessed Virgin of Pompeii Church, was razed in the 1960s to make way for the construction of Interstate 794. This sent the Italian community into its final diaspora around Milwaukee and its suburbs. The East Side and Brady Street became the new main Italian neighborhood site within the city. Glorioso’s Italian Market still provides an anchor for Italian food and groceries, and St. Rita’s Catholic Church, originally a “mission” outpost of Blessed Virgin of Pompeii, continues as a locus for Italian Catholicism.[10]

Milwaukee’s Italian immigrants have played a significant part in shaping the history of the city and region and remembering their heritage. Famed Milwaukee civil rights leader Father James Groppi, for example, hailed from the Bay View branch of the Italian community.[11] The Balistreri family started as fruit and vegetable peddlers in the 1920s and built the Sendik’s grocery chain.[12]

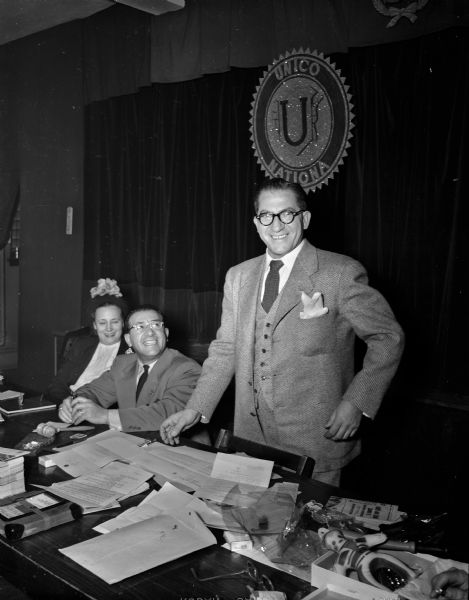

The community also has reaffirmed and maintained its cultural presence into the twenty-first century, as some 70,000 people in the Milwaukee metropolitan area report Italian ancestry in the American Community Survey.[13] The frequent “festas” that marked the commemorations of the early community have been reimagined as the annual Festa Italiana on the Summerfest grounds. In the 1970s, the Pompeii Men’s Club, founded in 1968 to maintain the memory of the “little pink church,” plus local chapters of the Italian-American service organization UNICO, organized to establish Festa Italiana and the Italian Community Center. The first Festa was held in 1978. The Italian Community Center opened that same year on Brady Street, moved to the upper East Side for a decade, and by 1990 opened its restaurant and meeting facility on East Chicago Street, in the heart of the Third Ward.[14]

Footnotes [+]

- ^ Italian Community Center, “Milwaukee Italians,” http://iccmilwaukee.com/milwaukee-italians.html, accessed November 1, 2017.

- ^ George La Piana, The Italians in Milwaukee, Wisconsin: General Survey (Milwaukee: Associated Charities, 1915).

- ^ La Piana, The Italians in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, 8.

- ^ La Piana, The Italians in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, 11.

- ^ Anthony Zignego, “Transatlantic Experience: Italian Migration and Immigrant Life in Milwaukee, 1890-1950” (Master’s thesis, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2009), 39ff; 82ff.

- ^ Alberto Meloni, “Italy Invades the Bloody Third: The Early History of Milwaukee’s Italians,” Milwaukee History (Summer 1987): 47-60.

- ^ La Piana, The Italians in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, 27.

- ^ La Piana, The Italians in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, 28.

- ^ Dominic Tortorice, “The Italian Story in Milwaukee,” Marquette Wire, accessed July 6, 2018.

- ^ Zignego, “Transatlantic Experience,” passim; Pompeii Men’s Club, “History,” accessed November 1, 2017; “About,” Three Holy Women parish website, accessed November 1, 2017.

- ^ Wisconsin Historical Society, “Marching for Civil Rights: A Brief Biography of Father James Groppi,” accessed November 9, 2017.

- ^ Sendik’s, “Our Story,” accessed November 1, 2017.

- ^ U.S. Census Bureau, American FactFinder, B04003, “Total Ancestry Reported, 2009-2013 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates.”

- ^ Italian Community Center of Milwaukee, “History: The Italian Community Center and Festa Italiana,” http://iccmilwaukee.com/history.html, accessed November 1, 2017, information now available at http://iccmilwaukee.com/history/.

For Further Reading

Andreozzi, John Anthony. Contadini and Pescatori in Milwaukee: Assimilation and Voluntary Associations. Milwaukee: s.n., 1974.

Carini, Mario A. Milwaukee’s Italians: The Early Years. Milwaukee: Italian Cultural Center, 1999.

Gordon, Michael A. “To Make a Clean Sweep’: Milwaukee Confronts an Anarchist Scare in 1917.” Wisconsin Magazine of History 93 no. 2 (2010): 16-27.

Hintz, Martin. Italian Milwaukee. Mount Pleasant, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2004.

La Piana, George. The Italians in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Milwaukee: Associated Charities, 1915.

Meloni, Alberto C. “Italy Invades the Bloody Third: Milwaukee Italians, 1900-1910.” Historical Messenger of the Milwaukee County Historical Society 25 (March 1969): 34-45.

Meloni, Albert Cosimo. “Milwaukee’s ‘Little Italy,’ 1900-1910: A Study in the Struggles of an Italian Immigrant Colony.” Master’s thesis, Marquette University, 1969.

Vecchio, Diane C. “Connecting Spheres: Women’s Work and Women’s Lives in Milwaukee’s Italian Third Ward.” Italian Americana 13, no. 2 (1995): 217-26.

Vecchio, Diane. “Gender, Domestic Values, and Italian Working Women in Milwaukee: Immigrant Midwives and Businesswomen.” In Women, Gender, and Transnational Lives: Italian Workers of the World, edited by Donna R. Gabaccia and Franca Iacovetta, 160-85. Toronto: Toronto Press, 2002.

Vecchio, Diane C. Merchants, Midwives, and Laboring Women: Italian Migrants in Urban America. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2006.

Zampogna, Ashley. “Canoli in the Cream City.” e.polis 3 (2009). http://www4.uwm.edu/letsci/urbanstudies/epolis/archive/2009/upload/canolicity.pdf.

Zignego, Anthony M. Milwaukee’s Italian Heritage: Mediterranean Roots in Midwestern Soil. Charleston, SC: History Press, 2009.

Zignego, Anthony M. “Transatlantic Experience: Italian Migration and Immigrant Life in Milwaukee, 1890-1950.” Master’s thesis, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2009.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.