The Milwaukee Journal Sentinel is Wisconsin’s largest and most influential newspaper. It is published daily in print and continuously in digital format (www.jsonline.com). The current publication is itself a result of the 1995 merger of two separate newspapers, the Milwaukee Sentinel, a morning paper, and the Milwaukee Journal, an afternoon paper. Both predecessor publications date from the nineteenth century. The long history of their political rivalry, different approaches to journalism, and eventual joint ownership and merger, has shaped Milwaukee print media for 150 years.

The Milwaukee Sentinel

The Sentinel is the older newspaper. It was founded on June 27, 1837 with financial backing of Solomon Juneau, the founder of Milwaukee who would become its first mayor. Its owner of record was John O’Rourke, who became its first editor. Within six months, he died of tuberculosis, setting the stage for a tumultuous first 50 years that saw 37 different editors, 27 changes of ownership, and 11 different names, all of which included the word “Sentinel.” O’Rourke was replaced by another strong editor, Harrison Reed, who is credited with strong leadership both editorially and financially, keeping the Sentinel going through tough early years, including a panic that almost took the paper under.[1]

Former Sentinel staffer Robert Witas, in his 1991 biography of the Sentinel, said its record “provides a profile of a fighting newspaper which, with rare exceptions, has lived up to the publication’s name.” From its start, the Sentinel was openly partisan, reflecting its times; openly Democrat the first year, then switching to Whig, then shifting its allegiance to the new Republican Party. Rufus King, editor from 1845 through 1861, promoted its Whig ties then led it to the Republican camp. The newspaper had been anti-slavery since its founding, with King’s editorials supporting the effort to free fugitive slave Joshua Glover in 1854. The Sentinel editorialized its opposition to the Fugitive Slave Act and the Kansas-Nebraska Act and its support for reversal of pro-slavery legislation, especially the Missouri Compromise. Its fervor on the anti-slavery issue was summed up in its announcing Abraham Lincoln’s election in 1860, saying “thanks to God, we are enabled to announce that ABRAHAM LINCOLN, of Illinois is the elect of the people.” King left the Sentinel, appointed by Lincoln as minister to the Papal States, a post he delayed since the Civil War broke out. King was appointed a brigadier general. Poor health eventually doomed his Army career, and King took up his ministerial post, later retiring to New York State. He would be replaced as Sentinel editor by another strong individual, Christopher Latham Sholes, who later invented the typewriter.[2]

For the remainder of the 19th century, the Sentinel struggled financially but held its own as one of Wisconsin’s leading newspapers, maintaining its politically activist role. At one point during this time, Lucius Nieman, who later became the dominant journalist at The Journal, served as Sentinel managing editor. In 1901, the newspaper was purchased by Milwaukee businessman Charles F. Pfister to oppose Robert La Follette’s Progressive movement. It openly battled controversial Milwaukee Mayor David S. Rose and opposed the rise of the Socialist Party in Milwaukee. The Sentinel was isolationist and antiwar. Even after the 1915 sinking of the liner Lusitania, it editorialized that Americans traveling on a British ship known to be carrying war materiel were “foolhardy.” The Sentinel supported Milwaukee’s German population, opposed The Journal’s anti-German campaign, and supported Charles Evans Hughes against Woodrow W. Wilson for the presidency. The Sentinel under Pfister’s ownership was a staunch opponent of women’s suffrage.[3]

After losing money for years, the Sentinel lost its local control in 1924, when it became part of the national Hearst chain. Hearst already owned another Milwaukee newspaper, the Evening Wisconsin. Under Hearst, it continued to oppose La Follette and Milwaukee’s Socialists. It continued to support Republicans. The Sentinel endorsed each of the opposing candidates during Franklin D. Roosevelt’s presidency, saying in 1940 that his re-election would be “the end of democracy.” The Sentinel editorially supported Wisconsin Senator Joseph McCarthy until his death. It called the Army-McCarthy hearings six weeks of distracting “irreverences” and editorialized at his death that McCarthy’s only motive was to “smash the Communist conspiracy” and that he had served the country well as a champion of liberty. It also ran a strong series under the byline of “John Sentinel,” accusing the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) unions of being under Communist control.[4]

A strike called by the American Newspaper Guild in 1962 was the pretext used by Hearst Corporation to shut down the Sentinel, by then Wisconsin’s oldest daily newspaper. Former Sentinel publisher Robert C. Bassett said the newspaper had lost money since before World War II. Later, Irwin Maier said the Journal Company “reluctantly” purchased the Sentinel “only to keep it from closing since we believed Milwaukee needed two newspapers.”[5]

The Milwaukee Journal

The Journal began humbly in 1882 as a four-page publication called The Daily Journal. It was founded by a Democratic congressman, Peter V. Deuster, who was editor of the Seebote, one of the city’s three German-language publications, and minority owner, Michael Kraus, the Seebote’s publisher. Deuster believed an English-language newspaper was needed to offset the Republican leanings of the city’s other English newspapers, the Sentinel and the Evening Wisconsin. However, within a month, Deuster decided the new newspaper was losing too much money. He opted to withdraw, opening the door to a young editor and majority owner, Lucius W. Nieman (1857-1935), who became Wisconsin’s most prominent journalist and who laid the foundation for the future dominance of The Milwaukee Journal and the Journal Sentinel.[6]

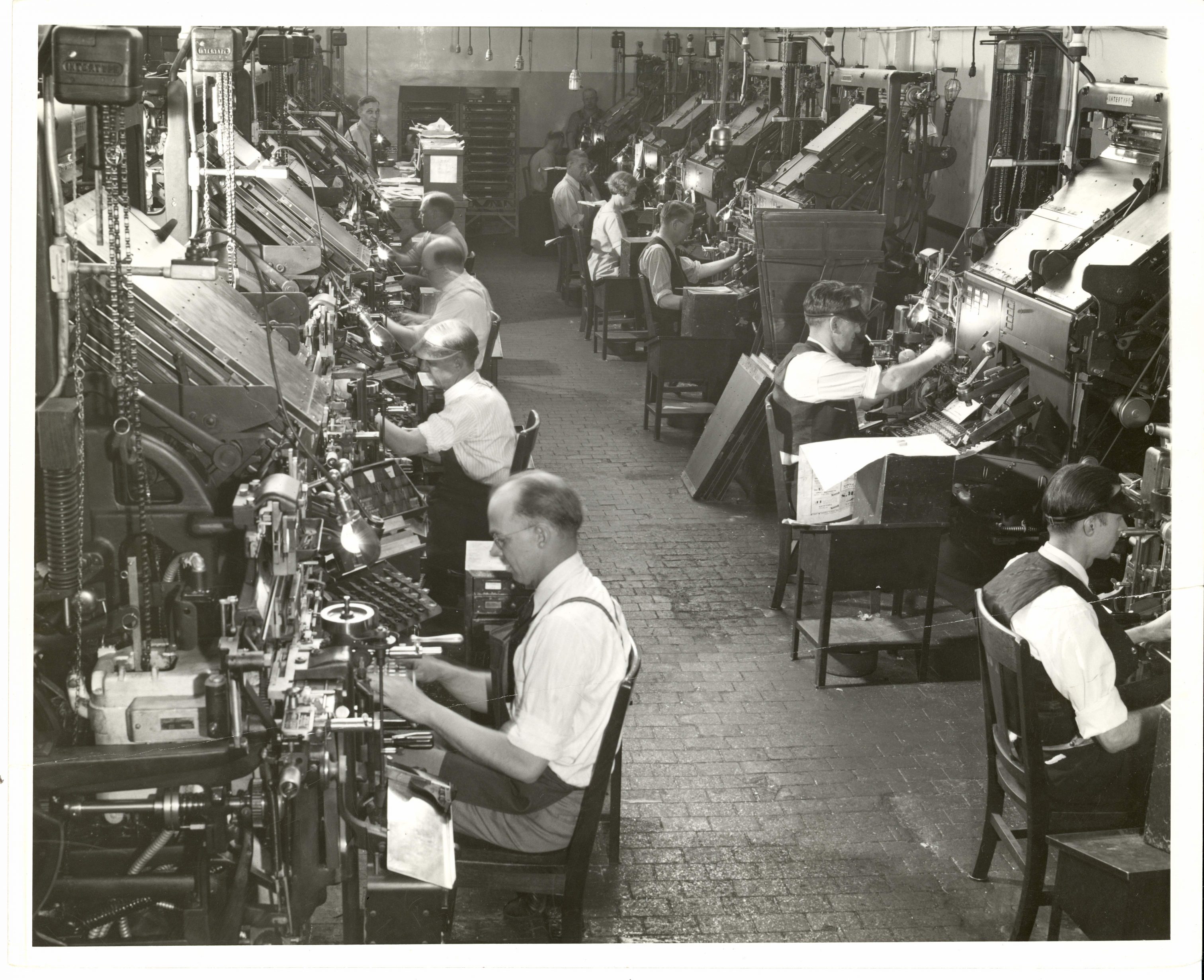

Nieman began working at age 12 as a typesetter for the Waukesha Freeman. While attending Carroll College, Nieman began writing and reporting local news for the Milwaukee Sentinel, quitting college after a year and a half to accept a reporting job for the Sentinel. He soon became city editor. He shortly moved to Minneapolis-St Paul to become editor of the St. Paul Dispatch, only to return to the Sentinel as managing editor after a year and a half. After the Sentinel was sold to a group and given a strong political slant, in 1882, Nieman purchased Deuster’s half interest in The Daily Journal, two days before his twenty-fifth birthday.[7]

In his first edition after taking control, Nieman set out a philosophy of political independence: “The Journal will be independent and aggressive….It will be the people’s paper.” Despite an early flirtation with becoming a partisan Democratic newspaper, The Journal hewed to a political stand of an independent, progressive newspaper. The Journal soon became noted for its strong local reporting, often with an activist agenda. Early examples included exhaustive coverage of a deadly fire with more than 75 casualties at the city’s most noted hotel, the Newhall House, with The Journal decrying a lack of anyone’s accountability in the fire; and statewide campaigns for improvements in mental health, prisons, and the state’s turn of the 20th century economic powerhouse, the lumber industry.[8]

Ironically, it was the newspaper’s aggressive reporting and activist agenda that led to its first Pulitzer prize—and some strong criticism. By 1914, Milwaukee’s German heritage was deeply embedded in its culture, although its numerous German-language newspapers had been consolidated over time to a single daily and 10 weeklies.[9]

Milwaukee’s German culture came face to face with world and national affairs when World War I broke out in Europe that year. The city was split as never before. Much of its ethnic German population supported Germany. The Journal took an opposing position, endorsing a beefing up of the U.S. military forces. Nieman, although of partial German heritage himself, began to suspect, as historian-journalist Robert Wells writes, “that a substantial number of Milwaukee German-Americans were guilty of…putting Germany’s interest ahead of loyalty to the United States.” Nieman reacted to his suspicions, hiring F. Perry Olds, a recent graduate of Harvard College, to translate articles and editorials from Milwaukee’s German press. After uncovering a number of “suspect” articles and editorials, The Journal published an article nine columns long citing the Germania-Herold’s bias under the headline “Disloyalty Flaunted in the Face of Milwaukee.” The article said the German newspaper preached division, worked to build support of the German positions, and opposed the United States “in every step that President Wilson has taken to protect American sovereignty and the rights of American citizens against the aggressions of Germany.” Other stories continued outlining bias in German newspapers, followed by a frontal attack on the German-American National Alliance, claiming the organization was conducting a campaign to bring the state’s German community into support of the German cause.[10]

Milwaukee’s German community was outraged. The response was almost immediate. Hundreds of subscribers cancelled their subscriptions to The Journal. Advertising salesmen were thrown out of offices. The paper received bomb threats serious enough that it installed floodlights and armed guards. Circulation slumped initially, but rebounded strongly, rising to over 116,000 in 1918. Despite the controversy over its coverage, The Journal was a unanimous winner of the Pulitzer Prize for “meritorious public service” in 1918 for its “campaign for Americanism in a constituency where foreign elements made such a policy hazardous from a business point of view.”[11]

The Journal and editor Nieman (a personal friend of President Woodrow Wilson) strongly supported the president’s wartime stance. He broke with progressive Robert La Follette after the Wisconsin senator had taken a strong antiwar position in a speech; attacked Milwaukee Socialist Congressman Victor Berger, who edited the Socialist newspaper, the Milwaukee Leader; and ramped up attacks on Socialist Milwaukee Mayor Daniel Hoan. Despite Wisconsin’s isolationist sentiments and its unpopularity, The Journal strongly supported the League of Nations. The anti-German campaign and crusade for Wilson’s policies “first attracted national attention” to the Journal and “developed an international outlook,” according to journalism historian Edwin Emery.[12]

Nieman had been the driving force at The Journal for three decades, but a new figure forged to the fore as World War I came to an end. Harry J. Grant had been hired earlier as advertising manager and proved to be a formidable businessman known for playing hardball with reluctant advertisers and starting a Sunday edition. In 1919, he took over control of the newspaper from an ailing Nieman. Grant was credited with successfully expanding the newspaper’s circulation and financial position and strengthening its editorial staff both in numbers and in quality. He hired future editors Marvin Creager and Donald Ferguson. The Journal of the 1920s to 1940s concentrated on strengthening itself economically and editorially, building its reputation with a strong, local editorial page and a stable of featured columnists such as Walter Monfried, Leslie Cross, Gerald Kloss, Richard S. Davis, Lewis C. French, and Ione Quinby Griggs. It became known for not only its “hard news” coverage, but strong features including a daily woman’s page, its daily feature section called “The Green Sheet” (it was printed on green paper and increased in 1934 to four pages including new, local features, names and photos of Milwaukeeans celebrating landmarks such as golden anniversaries, comics, and Griggs’ advice column); a beefed-up sports staff including noted sportswriters such as golf writer Billy Sixty, Oliver Kuechle, who was credited with bringing Green Bay Packers’ games to Milwaukee, and Russell Lynch, instrumental in bringing the Boston Braves baseball team to Milwaukee; and strong outdoor writers such as Gordon MacQuarrie, Mel Ellis, and Jay Reed.[13]

The Journal was also noted for two important photographic innovations; it was selected in the 1940s as the national’s outstanding newspaper in “quality of photos” by the Photographers’ Association of America, and was the first newspaper to offer full color photos. It had been experimenting with color printing since 1921 but did not perfect the process until 1937. It led the nation in color use until the 1960s.[14]

The newspaper was also a pioneer in radio and television, with writers going on radio to report news and features—even to offering a program with advice columnist Griggs in the 1930s. It founded WTMJ radio and later, WTMJ television, both of which quickly separated themselves from their close association with the newspaper.[15]

In 1935, the newspaper faced its biggest challenge with the death of Lucius Nieman and ended in a unique state among American newspapers. After a long illness, Nieman died 53 years after taking over leadership of The Journal. He also owned 55 percent of the company’s stock, with Harry Grant owning 20 percent and the heirs of his longtime partner L.T. Boyd the remaining 25 percent. His will left one-half of his holdings to his widow, Agnes Wahl Nieman, and the rest to a niece, Faye McBeath. Almost immediately, outside offers came for the newspaper, especially after Mrs. Nieman died within six months. Grant came up with another idea. He had long talked about employee-ownership as a way of keeping local control. Turning down higher offers from outsiders, a plan to preserve local control was agreed upon by creating The Journal Company. Stock was owned by a trust, with employees able to purchase units of interest in the trust, holding them until they died, retired, or quit, when they had to be sold to the trust, which would then resell them to eligible employees.[16]

The Journal Company also became the vehicle for acquiring the Sentinel in 1962. It replaced much of the newsroom’s managers. Harvey Schwander, assistant managing editor of The Journal, took over as Sentinel editor; Harry Sonneborn, Journal city editor, became Sentinel managing editor; and Robert Wills, Journal assistant city editor, became Sentinel city editor. Wills later became Sentinel editor and, still later, publisher of The Journal.[17]

Following World War II, The Journal and the Journal Company became very involved in civic affairs and joined with the city’s business community to support local economic development. They championed urban renewal, freeway construction, housing renovation, the promotion of professional sports and the arts, and investments in the Downtown area. With the business community uniting behind leaders in the Greater Milwaukee Committee and the strong support of The Journal and the Sentinel, city development went on a four-decade long seesaw of economic boom and bust that built on Milwaukee’s industrial base in the late 1940s but slowed with the manufacturing decline in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s.[18]

Milwaukee’s black population also grew dramatically after World War II. African Americans faced segregated housing markets, crowded schools, and employment discrimination, even as white city residents migrated to newer housing and opportunities in the suburbs. Belatedly, The Journal began to cover the growing racial divide in the city. Of immediate concern was a strong need for improved public housing. The Journal had editorially opposed Socialist Mayor Frank Zeidler, who pushed urban renewal projects. In 1960, Zeidler was replaced by Mayor Henry Maier, who became a target of the black community. Maier responded to criticism by blaming Milwaukee’s growing civil rights protests on lack of spending by state and federal officials and The Journal’s encouragement of “outside agitators.”[19]

It all came to a head in the summer of 1967 when Milwaukee became one of several cities to experience racial violence.[20] In the disturbance’s aftermath, the mayor was among those blaming coverage of civil rights protest by The Journal. On the other hand, many in the black community had long felt The Journal news coverage was racist. At that time, it had only one black reporter and a black student intern. (The Sentinel had no black staffers.) As the newspaper began trying to rebuild bridges to the black community, the city’s civil rights movement took up public housing with a vengeance, sponsoring open housing marches for 200 straight nights, which solidified Mayor Maier’s criticism of the newspaper. He felt the newspaper coverage fed racial division. The feud was so intense that Journal reporter Joel McNally was removed from a city meeting. The newspaper promptly sued and won an injunction permitting Journal reporters to attend all city meetings.[21]

Race remained a sore point, with lawsuits over both open housing and segregation in schools. The Journal quickly hired more black reporters and set up dedicated space for coverage of minority communities, including the city’s small but growing Latino population. Ironically perhaps, and little covered at the time, while the city’s economy entered a downward spiral as deindustrialization swept the Midwest, the 1970s were a glory time for The Journal’s news coverage. With strong newsroom leadership from editor Richard H. Leonard and managing editor Joseph Shoquist and the backing of the Journal Company’s leading executives Irwin Maier and Donald Abert, it solidified its reputation of one of the leading local newspapers in America. Its ambitions were supported by the highest advertising lineage in its history, which meant funding for reporting. In 1974, as it had four times previously, The Journal was named one of America’s ten best newspapers by both industry organizations and Time magazine. It covered major national and international stories as local, reporting on local connections to national and international developments. Time concluded that: “Although it does send reporters and editorial writers on international fact-finding tours, the paper’s thrust is unabashedly local.”[22]

Nevertheless, national and local weakness in the economy hit The Journal in the 1970s and 1980s, leading to a circulation retrenchment.[23] Meanwhile, the Journal Company continued to diversify during the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, acquiring several printing companies, cable television systems, an educational film company, and several radio and television companies. One winning acquisition was a microwave transmission company that captured signals from satellites and transmitted them to news organizations in Wisconsin and California. In 1977, Maier retired, with Donald B. Abert becoming company chairman and Thomas J. McCollow taking control. With the company purchasing more stock owned by Grant’s heirs, employee ownership hit 90 percent of outstanding stock in 1979.[24] Richard Leonard retired in 1985. His replacement was editorial page editor Sig Gissler, who began aggressively updating the newspaper’s editorial structure. Nicola Pring reviewed Gissler’s tenure as he retired. “As editor of The Milwaukee Journal from 1985 to 1993,” she reported, “he focused much of his energy on increasing newsroom diversity and improving coverage of racial issues.”[25]

Gissler resigned in 1993. He was replaced by the newspaper’s first editor from outside its ranks in more than a half-century. Mary Jo Meisner had been managing editor of the Fort Worth Star-Telegram after stints on other newspapers, including the Washington Post. She came to Milwaukee to design a new newspaper. Two years later, The Milwaukee Journal merged with the Sentinel.[26]

The Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

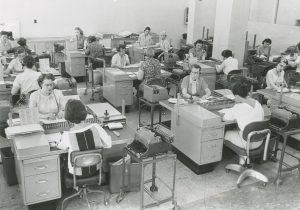

At the time of merger, the employee-owned corporation controlled both newspapers. The staffs of both papers were consolidated, with many employees retiring, leaving, or being laid off. The merged Milwaukee Journal Sentinel began producing its digital edition, with its uncertain financial funding model. Like other metropolitan newspapers, after the turn of the 21st century the combined Journal and Sentinel faced further declines in both readership and advertising, especially in the very profitable classified advertising. This was reflected in an almost-yearly set of staff reductions, resulting in a decline in reporters and editors from more than 300 at The Journal and about 180 at the Sentinel at the time of merger, to a much lower number today. In 2003, The Journal Company was renamed Journal Communications, Inc. (JCI).[27]

Nevertheless, the newspaper did some of its finest work ever; its work was awarded national honors virtually every year, including Pulitzer prizes won by reporters David Umhoefer (local reporting, 2008), Raquel Rutledge (local reporting, 2010), and the team of Mark Johnson, Kathleen Gallagher, Gary Porter, Lou Saldivar, and Alison Sherwood (explanatory reporting, 2011).[28]

In 2003, the merged newspaper also gave up its prized employee ownership, as Journal Communications, Inc. changed to public ownership, with its stock listed on the New York Stock Exchange. JCI CEO Steven Smith spearheaded the move. Initially public ownership seemed a profitable step, with the stock price stock price increasing from its initial offering price of $15.00 a share on September 29, 2003 to a high of $20.10 on February 13, 2004. However, it soon began a long decline, dropping as low as 49 cents a share on March 6, 2009.[29]

Former CEO Irwin Maier had openly boasted that the company’s stock had increased in value every month since the employee-ownership plan was inaugurated in 1935 “including every month during the Great Depression and World War II.” As the stock continued to slide, the company increased belt-tightening steps, especially cutting staff.[30]

Twenty years after the merger, the public corporation was absorbed in a merger with the E.W. Scripps Co. based in Cincinnati. The combined corporations’ newspapers were separated from their broadcast properties, joining a newly-formed corporation, Journal Media Group, controlled by shareholders dominated by those of the former Scripps newspaper chain. The stock price slowly climbed back up to a price of about $12.00 per share in 2015 as the new corporation agreed to be acquired by Gannett.[31]

Footnotes [+]

- ^ Robert A. Witas, “‘On the Ramparts’: A History of the Milwaukee Sentinel” (Master’s thesis, History, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 1991), 3-7.

- ^ Witas, “‘On the Ramparts,” 7-8, 25-31, 35-36, Sentinel quote on Lincoln’s election from Witas, 30.

- ^ Witas, “‘On the Ramparts,” 54, 59, 62, 66; “Points to Consider,” Milwaukee Sentinel, May 11, 1915.

- ^ Witas, “‘On the Ramparts,” 75, 84, 89-91.

- ^ Witas, “‘On the Ramparts,”. 100, 105; Private conservation, Irwin Maier and Steve Byers (who was chairman of the company’s unitholders’ Council at the time), Maier’s office, 1982.

- ^ Theodore Mueller, The Milwaukee Press (1936?), unpublished manuscript, Archives Department, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Libraries, p. 12. Will C. Conrad, Kathleen F. Wilson, and Dale Wilson, The Milwaukee Journal: The First Eighty Years (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1964), 3-5.

- ^ Conrad, Wilson, and Wilson, The Milwaukee Journal, 5-9.

- ^ Newhall House Hotel Fire, Wisconsin Historical Society website, accessed October 12, 2015; Conrad, Wilson, and Wilson, The Milwaukee Journal, 18-19, 11-16.

- ^ Robert W. Wells, The “Milwaukee Journal”: An Informal Chronicle of its First 100 Years (Milwaukee: Milwaukee Journal, 1981), 93-97. The largest circulating English-language paper, according to the new Audit Bureau of Circulation, was the Evening Wisconsin (89,938 readers), followed by The Journal (76,060), the Sentinel (53,367), then the much-smaller Free Press, Milwaukee Leader (a Socialist newspaper), Germania-Herold (German language), Daily News, and Nowiny Polskie (Polish language).

- ^ Wells, The Milwaukee Journal, 96-97, 102. Conrad, Wilson, and Wilson, The Milwaukee Journal, 86-88.

- ^ Wells, The Milwaukee Journal. 115.

- ^ Edwin Emery, The Press and America, 3rd ed. (New York, NY: Prentice-Hall, 1972), 662. Wells, The Milwaukee Journal, 89-102.

- ^ Wells, The Milwaukee Journal, 113-115.

- ^ Wells, The Milwaukee Journal, 117-124; Conrad, Wilson, and Wilson, The Milwaukee Journal, 124.

- ^ Conrad, Wilson, and Wilson, The Milwaukee Journal, 140-151. Wells, The Milwaukee Journal, 456-458.

- ^ Conrad, Wilson, and Wilson, The Milwaukee Journal, 44-45, 175-181; Wells, The Milwaukee Journal, 283-287. When the plan was originally set up, the company’s stock was divided into four, with the employee-owners, Grant, McBeath and the Boyd heirs owning equal amounts. Over the years, the company bought stock for the employee trust from the private owners until by 1979 they owned 90 percent.

- ^ Conrad, Wilson, and Wilson, The Milwaukee Journal, 206. Chip Rowe, “Bylines,” American Journalism Review, 1993, accessed November 18, 2015. The Sentinel had a number of notable reporters and editors during the 20th century. Louise Fenton Brand became the first woman city editor on a Milwaukee daily newspaper in 1909. She left the Sentinel in 1915. It was 50 years before another woman was promoted to a city editorship. Then Gerry Hinkley took over the Sentinel’s desk. Longtime sports editor Lloyd Larson was a force in Wisconsin sports, especially high school sports (he was a longtime member of the Milwaukee School Board). George Pitrof ran the city’s press room and became a legendary police reporter. Local columnists Bill Janz and Alex Thien were widely read, while business editor D. Raymond Kenney was a force in not only covering Milwaukee business but also in shaping it. Editorial Cartoonist Stuart Carlson won national awards, including recognition as the nation’s best cartoonist in 1991 by the National Press Foundation. Witas, “On the Ramparts,” 66, 82-93. National Press Foundation, 1991, accessed January 3, 2016.

- ^ Jack Norman, “Congenial Milwaukee: A Segregated City,” in Unequal Partnerships: The Political Economy of Urban Redevelopment in Postwar America, ed. Gregory D. Squires (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1989), 178-184. The early period was marked by relocation of the Boston Braves baseball franchise to Milwaukee, construction of two major museums, a civic center, zoo, a major library addition, expressways, and an airport. All were strongly supported by The Journal.

- ^ Paul Geib, “From Mississippi to Milwaukee: A Case Study of the Southern Black Migration to Milwaukee, 1940-1970,” Journal of Negro History 83, no. 4 (Autumn 1998): 178-184. Richard M. Bernard, “Milwaukee: The Death and Life of a Midwestern Metropolis,” in Snowbelt Cities: Metropolitan Politics in the Northeast and Midwest since World War II, ed. Richard. M. Bernard (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1990), 172-177. The community, forced by housing patterns into increasingly dilapidated housing in a four-square-mile central city area, joined with civil rights movement seeking integrated schools and open housing. Maier procrastinated, saying he was waiting for the city’s suburbs to open their housing to minorities.

- ^ Frank Aukofer, City with a Chance: A Case History of Civil Rights Revolution (Milwaukee: Marquette University Press, 2007 [1968]), 7. Bernard, “Milwaukee,” 180.

- ^ Genevieve G. Caspari, “Media Performance at the Inflection Point: Coverage of Racial Conflict in Milwaukee in 1967” (Master’s thesis, Communication, Journalism and Performing Arts, Marquette University, 1982), 51; Joe William Trotter, Jr., Black Milwaukee: The Making of an Industrial Proletariat, 1915-45 (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1985), 116; Wells, The Milwaukee Journal, 439.

- ^ Geib, “From Mississippi to Milwaukee,” 243-244; Norman, “Congenial Milwaukee,” 181-183; Wells, The Milwaukee Journal, 437, 446-453, 462-3; “Ten Best American Dailies,” Time, January 21, 1974, accessed March 24, 2009. The newspaper’s strong reporting was based on a veteran and skilled staff, with many of them winners of national honors. Included were Mildred Freese and Douglas Armstrong on consumer affairs; James Spaulding, Paul G. Hayes and Harry Pease on science and medicine; Steve Byers on the brewing industry and beer; Mike Drew on television; and the strong sports staff built by sports editor Bill Dwyer. One weakness of the staff became apparent in the early 1970s—a lack of women reporters and editors—which was alleviated by a major expansion of the number of women reporters. Their widened responsibilities included overseas trips to Israel by Alicia Armstrong, and reporting on the elderly, which led to a Pulitzer Prize (the paper’s fifth) by Margo Huston in 1977. At the same time, several women moved into leadership positions in the newsroom, including assistant news editor Ruth Wilson, sportswriter Tracy Dodds, and Sandra Cota on the state desk, along with Beth Slocum and Barbara Dembski in features.

- ^ The paper cut coverage in Michigan and outstate in Wisconsin. Journal circulation had been steadily declining since it marked its all-time high in 1963 of 373,326 newspapers daily and 567,042 on Sunday. After the retrenchment, it concentrated on a four-county area around Milwaukee. It went through a major technical change in 1976, switching to an offset-type printing system. Also of significance in this era was a newsroom reorganization strengthening features and suburban coverage at the cost of some traditional city coverage, and a new design including moving the paper’s editorial cartoon from the front page to the industry-norm editorial page placement. The front page editorial and cartoon (which won a Pulitzer Prize in 1934 for cartoonist Ross Lewis) were Journal trademarks. Wells, The Milwaukee Journal, 280, 444-446, 454, 470.

- ^ Wells, The Milwaukee Journal, 438, 456-458.

- ^ Norman, “Congenial Milwaukee,” 192; Nicola Pring, “Exit Interview: The Man Behind the Pulitzer,” Columbia Journalism Review (2014), accessed January 3, 2016.

- ^ Chip Rowe, “A New Leader in Milwaukee,” American Journalism Review (June 1993), accessed January 3, 2016; William Glaberson, “An Editor Mindful of the Bottom Line,” New York Times, June 19, 1995, accessed January 3, 2016.

- ^ Gores, “Gannett to Buy Journal Media Group,” Encyclopedia.com, accessed April 4, 2016.

- ^ “Journal Sentinel Pulitzer Prizes,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, accessed January 3, 2016. Previously, Journal staffers had won Pulitzers in 1919, 1935, 1953, 1967, and 1977.

- ^ Journal Communications, Inc., Google Financials.

- ^ Private conservation, Irwin Maier and Steve Byers (who was chairman of the company’s unitholders’ Council at the time), Maier’s office, 1982.

- ^ Caroline Micheli, “E.W. Scripps Company Completes Merger, Spinoff Transaction with Journal Communications,” Scripps, April 1, 2015, accessed April 27, 2016; Paul Gores, “Gannett to Buy Journal Media Group, Parent of Journal Sentinel, for $280 Million.” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, October 7, 2015.

For Further Reading

Conrad, Will C., Kathleen Wilson, and Dale Wilson. The Milwaukee Journal: The First Eighty Years. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1964.

Milwaukee Sentinel, 150 Years: Our Anniversary Celebration. Milwaukee: Milwaukee Sentinel, 1987.

Wells, Robert W. The “Milwaukee Journal”: An Informal Chronicle of Its First 100 Years. Milwaukee: Milwaukee Journal, 1981.

See Also

Explore More [+]

Understory

Deciphering the Google News URL

The availability of Milwaukee newspaper archives through Google News[1] is a real boon to research for the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee. Writers can delve into their entry research through a precisely targeted search; they no longer have to wade through reels and reels of microfilm[2] in search of a few relevant articles. Fact-checkers can hone in on exactly the articles they needed to see to verify or disconfirm particular pieces of information. Readers who follow the URLs provided in entry footnotes can see articles from the Milwaukee Journal, the Milwaukee Sentinel, and the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel in their original contexts, gaining access not only to information but to the look of old newspapers and to the content that surrounded the material they were interested in.

So you can imagine the dismay in the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee offices when the Google News archive of Milwaukee’s newspapers abruptly disappeared in 2016[3] and stayed missing until December 2017.[4] We experienced several kinds of problems due to the disappearance of the archive. It shifted the kind of research that could go into our entries because of the prohibitive amount of time required for manual search in microtext. Fact-checking became more time-consuming because our staff could not gain instant access to the content they needed; instead of working from their computers they had to trek to the UWM library’s basement microfilm room and scroll through many irrelevant issues to locate the right page. Entries that had already been posted were littered with dead links. And even as we got used to working without the digital archive, we faced a problem we had not initially imagined: incomplete footnote citations.

When we began envisioning the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee as a digital platform, we decided to include footnotes—which do not usually appear in printed encyclopedias (though are very useful on Wikipedia). In our successful grant application to the National Endowment for the Humanities, we wrote:

In other ways the Underbook will innovate. Traditional print encyclopedias—and most online encyclopedias, to date—do not contain footnotes, although many include “for further reading” bibliographies with each entry. The Underbook will provide citations for which there is no room in a print project. The use of footnotes will also mitigate (though not obviate) the necessity for an expensive process to fact-check the veracity of every piece of information included in the project…Including such stories about how the research process works will teach readers about the nature of historical research, the overall reliability of the EMKE, and the ephemeral character of certain “facts,” all ideas crucial for understanding how historical knowledge is built and presented.[5]

We did not want to overwhelm readers with a sea of footnote markers when they landed on any given entry page, so we tucked access to them under the author byline on each page. If you want to see the footnotes for an entry, click on the [+] next to the word Footnotes.

Including footnotes meant encouraging authors to provide citations documenting their research. Not everyone who writes for the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee is a professional historian practiced in adhering to our picky documentation standards, so we often accepted entries with links to online news articles—including Google News Archive links—with the intention of filling out the rest of the citation as we fact-checked and copyedited the article. We were prepared to add an article author’s byline, the title of the article, and the date that it was originally published. With the disappearance of the archive, however, we were sometimes left with dead links and no way of reconstructing the citation to the original newspaper article so that an interested reader could look up the microfilm version.

Thus began the task of trying to decipher what the URL for a Google News archive meant. The available online documentation is written for audiences with a much higher level of technical sophistication than we historians possess and required its own translator,[6] so we decided to figure it out the old-fashioned way.

Our theory was that there must be a pattern to our dead links. Armed with this belief, we chose an entry on which to run an experiment. We noticed that the links in question contained the phrases “nid=1368”[7] or “nid=1499”.[8] The assumption was these phrases differentiated the Milwaukee Journal from the Milwaukee Sentinel, but how? After each nid=1368 or nid=1499 was an eight-digit number; were these numbers dates? We thought probably, but we had to check. There was one way to find out: take our assumptions and delve in UWM’s microtext library, where the microfilms of old newspapers and all sorts of other compact treasures are stored.

The first dead link we decided to verify was nid=1368 followed by the number 19680726. Our search began with the July 26, 1968 issue of the Milwaukee Journal; our topic, ballet and the Milwaukee County Performing Arts Center. After scanning every page of the paper for that date, we found nothing. We then tried our information against the Milwaukee Sentinel[9] issue of the same date. BINGO! We had a winner. We followed this same process for our next test link which was nid=1499 and the eight digits, 19860928. Again, we began with the Milwaukee Journal[10], only this time fairly confident that we would find the article relating to ballet that we were searching for. Scanning the September 28, 1986 issue page by page, we indeed found said article. We next searched the microfilm of the Milwaukee Sentinel for that day; it turns out that September 28 was a Sunday and no paper was included for that day on the microfilm. We therefore concluded that we were on to something; further testing with a larger pool was needed to confirm our results.

For our second experiment, we pulled four entries that contained a total of twenty-two different footnotes which used Google News as a source for Milwaukee papers. The origins of the phrases in question were easier to determine this time, as the footnotes for these entries included full Chicago Manual of Style citations.[11] Still we felt it necessary to research each entry in the microtext library to substantiate our original thinking. Verification of this larger pool offered up the opportunity to verify a new phrase nid=1683,[12] which we believed was probably the signifier used to indicate the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel subsequent to the merger of the papers in 1995. Our research was fruitful; a majority of the citations used matched up beautifully. Of the twenty-two citations listed amongst all four entries, we found only four total anomalies. One citation was given as April 8 when the article appeared in print on April 9. In another case, a cut and paste error included information from the main search bar for an article from July 1998 instead of the Google News search bar for the actual January 1989 article, causing discrepancies between the two portions of the citation. The final anomaly was one in which the cited Google News phrase was inconsistent with the pattern we established, an id= of 6qpRAAAAIBAJ&sjid without date indicator appeared as the citation, a mystery we have yet to explain.

The December 2017 return of the online archives allowed us to do some further interpretation of the strings. The Milwaukee Journal Sentinel article announcing their return differentiated the current newspaper from its two predecessors with strings that looked nothing like the compact four digit codes we had just figured out:[13]

- Milwaukee Journal: https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=jvrRlaHg2sAC

- Milwaukee Sentinel: https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=wZJMF1LD7PcC

- Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=OP2qWFMeUpEC

If you click through those links, they bring you to an opportunity to browse digital facsimiles of the newspapers. If you further click on one of the pages, the URL expands to include what appear to be a date string and further information indicating the section of the newspaper you are looking at. What, then, are our four digital “nid” codes? It appears that they are generated when a user searches through the archive of a particular paper for a particular article, and that the longer combination of letters and numbers supports the browse function.

To summarize, then, we managed to interpret the first portion of the identification code generated in a search of the Google News Digital Archive for a particular article. 1368 is the Milwaukee Sentinel; 1499 is the Milwaukee Journal; and 1683 is the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Each “nid” (newspaper id?) is followed by a date. There is yet more information embedded in each string that we have not tried to unpack systematically, but it seems likely that the URL also has encoded the newspaper’s section and placement on the page. We are glad to have access to the digital archive once again so that we can continue to learn how it works.

Footnotes [+]

- ^ Google News site, accessed September 22, 2017.

- ^ As EMKE fact-checker Jacob Rindfleisch reminds us, microfilm and the internet play nicely together. See Jacob Rindfleisch, “How Microfilm and the Internet Get Along: A Demonstration,” s.v. Borchert Field, Encyclopedia of Milwaukee (follow “Understory” link).

- ^ Henry Grabar, “Why Milwaukee’s Online Newspaper Archive Vanished Overnight,” Slate, August 24, 2016, last accessed September 22, 2017; Michail Takach, “Journal Sentinel Archive Disappears,” Urban Milwaukee, August 19, 2016, last accessed September 22, 2017; Bob Warburton, “Newspaper: Disappearing Archive Only Temporary,” Library Journal, September 1, 2016, last accessed September 22, 2017; Matt Wild, “For What It’s Worth, There’s a Petition to Restore Old Journal Sentinel Issues to Google News Archive,” Milwaukee Record, August 23, 2016, last accessed September 22, 2017; Jay Bullock, “The Missing JS Archives and the Digital Age’s Great Failure,” OnMilwaukee.com, September 6, 2016, last accessed September 22, 2017.

- ^ “Milwaukee Journal and Sentinel Newspaper Archives Are Back on the Web,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, December 20, 2017, last accessed December 29, 2017.

- ^ Encyclopedia of Milwaukee, National Endowment for the Humanities Grant Application, Humanities Collections and Reference Resources, 8-9.

- ^ Google News Search parameters (The Missing Manual), October 19, 2013, last accessed December 29, 2017.

- ^ The full string we were looking for was https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1368&dat=19680726&id=aYdQAAAAIBAJ&sjid=YxEEAAAAIBAJ&pg=6062,5106895&hl=en

- ^ The full string we were looking for was https://news.google.com/newspaper?nid=1499&dat=19860928&id=S2caAAAAIBAJ&sjid=CCsEAAAAIBAJ&pg=4869,3553733&hl=en

- ^ “Ballet Company in City’s Future,” Milwaukee Sentinel, July 26, 1968, Microfilm.

- ^ Tom Strini, “Ballets of Today Will Dance Away,” Milwaukee Journal, September 28, 1986, Microfilm.

- ^ The EMKE entries we selected for further testing were Michael Pulido, “City of Festivals Parade”; Elissa Cahn, “Literary Milwaukee”; Yance Marti, “MECCA”; Catherine Jones, “Milwaukee Exposition Building.”

- ^ Jackie Loohauis, “City’s Great Promoter,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, February 3, 2001, Microfilm. The Google News string is https://news.google.com/newspaper?nid=1683&dat=20010203&id=2bMaAAAAIBAJ&sjid=ojAEAAAAIBAJ&pg=6881.2055343. This information was cited in Michael Pulido, “City of Festivals Parade.”

- ^ Craig Nickels, “Milwaukee Journal and Sentinel Newspaper Archives Are back on the Web,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, December 20, 2017.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.