Milwaukee’s past includes an inestimable number of nonhuman animals: germs; animals raised in or transported to the city for slaughter; working and service animals; wild, zoo, and laboratory animals; pets; and stray and abandoned domestic animals. The city’s earliest ordinances, passed by 1856, regulated horses, livestock, and dogs as well as soap factories, tanneries, stables, and other potentially “unwholesome, nauseous” businesses that serviced animals or rendered their parts into products for human consumption.[1]

Animals for Food and Other Products

Many early industries depended on animal slaughter and the processing of pelts, meat, and hides. The city was founded around the fur industry; later, fishing was an economic mainstay, especially for the residents of Jones Island; and by the end of the nineteenth century Milwaukee had become one of the leading producers of pork in the country as well as a global center of the tanning industry. Cattle and hogs were shipped by train and later by motor-transport to the eleven-acre Milwaukee Stockyards, opened in the Menomonee Valley in 1869. During the early decades of the twentieth century over a million hogs and around 500,000 calves passed through the stockyards each year, the majority being turned into meat in the huge slaughterhouses that from the late nineteenth century into the 1950s stood among the city’s landmarks.[2] Despite the move of the Milwaukee Stockyards to Dodge County in 2004 and the decline of the local meatpacking industry, the region maintains a close cultural association with animal slaughter as each summer farm animals are brought to West Allis for exhibition and competition at the Wisconsin State Fair. At the fair’s end, restauranteurs, butchers, and other bidders compete in the Governor’s Blue Ribbon Livestock Auction to purchase champion steers, barrows (castrated pigs), and lambs.

Working, Service, and Show Animals

Milwaukeeans have also long benefitted from animal service, ranging from the provision of power to entertainment and sport. In the past horses pulled wagons for the beer and other industries, fire engines (through 1927), streetcars (from 1860 to roughly 1890), and trash wagons (through 1952).[3] The area’s current working animals include horses serving with the Milwaukee Police Mounted Patrol and the Sheriff’s Mounted Unit, police dogs, and service and therapy animals.

For decades people rode and drove horses across the Milwaukee countryside for transportation and pleasure; some raced with them as well. As Solomon Juneau observed in the early 1800s, the Potawatomi staged equestrian exhibitions, including pony races.[4] Later settlers organized recreational parties of horse-driven sleighs, while others raced in sleighs over a stretch of the Milwaukee River near Cherry Street.[5] Although by 1856 Milwaukee’s charter gave the Common Council authority to “prevent horse racing, immoderate riding or driving in the streets,”[6] private and public parks helped meet the post-Civil War demand for equine-related sports. Until its closing in 1891 Cold Spring Park, a private park on the west side that hosted the Wisconsin State Fair on and off between 1852 and 1890, was a major venue for harness training and racing.[7] Other popular racing sites included: National Park, a private park with a half-mile track that lured “thrill seekers” to Milwaukee’s south side from 1883 to 1899;[8] Washington Park, which opened in 1891 as “West Park” and offered a one-mile track and (from 1892) Milwaukee’s early zoo;[9] and Wisconsin State Fair Park. With its purchase of the site that became State Fair Park in 1891, the Agricultural Society of the State of Wisconsin acquired a one-mile track. Harness racing continued on the track (which came to be known as the “Milwaukee Mile”) until its full conversion to auto racing in 1954, after which horses raced on a smaller interior track. The State Fair eliminated harness racing from its annual program in 1958 but since the 1980s pigs have raced around a small track for fairgoers’ entertainment.[10]

Another segment of the region’s horse community focused on the breeding and showing of horses. Here Captain Frederick Pabst, who bred Percherons in addition to employing them to pull Pabst Brewery wagons, was a leader. His family participated in (and for many years Pabst Farms hosted) the Oconomowoc Horse Show, which began in the 1920s and continued (with a four-year interruption during the Depression) until 1948.[11] In 1903 Gustave Pabst and other horse fanciers gathered at the Exposition Building for the first of the grand horse shows staged in the City of Milwaukee.[12] Coming to be known as the Milwaukee Spring Horse Show, the event moved to State Fair Park, its setting for many years until organizers relocated the event to Madison in 2007.[13] Held in Milwaukee thirty summers between 1963 and 2009, the Great Circus Parade was an animal-related extravaganza that in some years showcased seven or so hundred horses and helped keep Milwaukee on the summer tourism map. A nostalgic celebration of the circus and its associated draft and performing animals, the parade featured large equestrian clubs and spectacular hitches of draft horses (including Belgians, Clydesdales, and Percherons) pulling circus wagons while lions, tigers, camels, and elephants either rode in the wagons or marched through the streets as if on their way to one of the many circus performances of old Milwaukee.[14]

Celebrity Animals

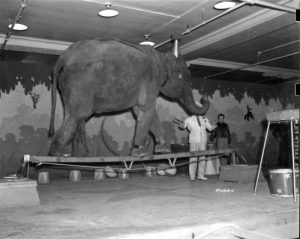

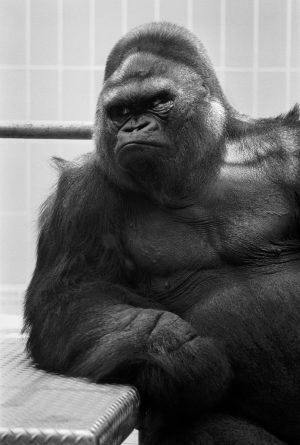

Individual animals have enjoyed celebrity standing and close, if sometimes fleeting, relationships with the people of Milwaukee. In a period when an elephant was thought to “make a zoo,” the acquisition of the Asian elephant Countess Heine in 1907 symbolized the coming-of-age of the Washington Park Zoo. The “pet” of Milwaukeeans for many years, she was, however, replaced by Venice, a younger and also celebrated elephant, in 1926.[15] Sultana, a polar bear who lived at the zoo from the 1910s until her death in 1947, enjoyed international fame when in 1919 she gave birth to Zero, the first polar bear born in captivity to survive.[16] The massive size and personality of Samson, a lowland gorilla brought to the zoo in 1951 (a decade prior to its relocation and reopening as the Milwaukee County Zoo[17]), so captivated Milwaukeeans that the zoo temporarily lowered its American flag to half-staff upon his death in 1981, a gesture of respectful mourning that some Milwaukeeans questioned.[18] Lota, an elephant who resided at the zoo from 1954 to 1990, inspired local and national outrage when the zoo sold her to a company engaged in animal entertainment. Although she died at the Hohenwald Elephant Sanctuary in 2005, Lota remains an international symbol of elephant exploitation.[19] Perhaps the most famous of the locally celebrated wild animals was Gertie, who during World War II inspired Milwaukeeans as she struggled to raise ducklings in downtown Milwaukee.[20]

Animals in Public Art

Milwaukee’s public art has embraced animals, in a tradition that perhaps extends to American Indian effigy mounds, which have been interpreted as depicting a variety of animals including birds, turtles, and snakes.[21] Milwaukee is home to equestrian sculptures of Thaddeus Kosciuszko and Frederick Wilhelm von Steuben. Incorporating an animal motif and displayed so as to serve the needs of real animals, the Henry Bergh bronze catches the founder of the American humane movement as he leans over to pet an injured dog. It originally sat atop a thirty-foot wide watering trough for dogs and horses. Dedicated in 1891, the statue enjoyed a place of prominence on Market Square, just south of City Hall, but, after a series of relocations, the statue (minus the trough) became a permanent fixture at the no-kill animal shelter run by the Wisconsin Humane Society (WHS) on Wisconsin Avenue. Although livestock animals are largely absent from Milwaukee’s public sculpture, the first segment of “Milwaukee, 1989” (a sculpture on the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee campus) depicts a pastoral scene of a farm couple with a cow.[22]

Some area monuments witness to the memory of individual animals. Commissioned by Richard Whitehead (first superintendent of the WHS), a remarkable monument on South 16th Street features a bronze bas-relief of Whitehead’s horse George and dog Dandy, set in a granite base that functioned as an animal watering trough when first erected in 1910. In Lake Park an equestrian monument of 1920 memorializes Erastus Wolcott and Gunpowder, a nineteenth-century physician and his equine partner known for their long medical rounds through Milwaukee and its environs.[23] Samson, like Gertie, earned an individual sculpture, for which the taxidermist Wendy Christensen-Senk used some of Samson’s own hair and his death mask. This life-size sculpture now sits in the Milwaukee Public Museum with thousands of Milwaukee animals whose bodies or parts the science and art of taxidermy transformed into museum specimens.[24] These include Sambo (Samson’s zoo mate),[25] the Milwaukee-area muskrats captured by Carl Akeley for his ground-breaking diorama of 1891, and companion dogs and cats inhabiting houses within the museum’s European Village.

Pets and Animal Control

The museum’s dog and cat specimens speak to the legacy of pet keeping that early immigrants brought to the city. Already by 1856 Milwaukee was issuing dog licenses, then mandated only for dogs allowed to run at large; by 1875 licenses were required for all dogs.[26] In 1977 the state granted Milwaukee County authority to enact an ordinance obliging cat owners to purchase licenses.[27]

Against a background of ever tightening animal control measures, combined with concern for pet owners’ rights and humane animal treatment, Milwaukee struggled to maintain a pound for the rounding up, care, and disposition of the thousands of domestic animals who from the late nineteenth century to the present have strayed or been abandoned each year. From 1906 to 1930 the reformer Lenore Cawker used her family inheritance and small amounts of city and county support to run the first Milwaukee pound committed to humane euthanasia.[28] When in 1939 the county decided to fund a pound, the WHS accepted the contract. In 1996 the WHS decided to abandon service as a pound and the next year these responsibilities were delegated to a new inter-governmental body, the Milwaukee Area Domestic Animal Control Commission.[29] Since the 1960s concerned area residents have set up many additional animal welfare groups, some with shelters, including the Human Animal Welfare Society of Waukesha County.[30]

Pet Necessities and Amenities

Over the last century Milwaukee has added a wide array of businesses catering to necessities and amenities for companion animals and their keepers, ranging from small-veterinary clinics to animal cemeteries. By 1908 E. M. Sullivan, a local veterinarian, had established an animal cemetery on Swan Farm, near Wauwatosa.[31] Current area options for pet burial or internment of cremains include Pet Lawn, dating back to 1943;[32] Companion’s Rest, the animal section of Forest Hill Memorial Park; and the WHS’s Lorraine’s Garden, featuring a chapel and columbarium built in 2007.[33] During the last few decades emergency veterinary clinics, pet day care centers, and off-leash dog parks have claimed places in Milwaukee’s animal-human landscape. The pioneering, privately run Granville Dog Park opened in 1998 and, under pressure from groups such as Residents for Off-Leash Milwaukee Parks (ROMP), Milwaukee County established dog exercise areas in another half-dozen of its parks.[34]

Laboratory Animals

Like other American cities, Milwaukee has at times been a focal point for advocacy for dogs, rats, and other nonhuman animals whose lives end in medical and scientific laboratories. Near the end of World War II—during which as many as three hundred of Milwaukee’s canines served with Dogs for Defense[35]—Marie Graves Thompson, president of the local Animal Protective League, spearheaded a drive for a statewide ban on dog vivisection. Proposed in early 1945 by Assemblyman Roman Blenski of Milwaukee, the anti-vivisection bill failed to clear the State Assembly.[36] More recently, Wisconsin’s Act 32 (2011) removed any protection that laboratory animals at educational or research institutions may have enjoyed under the state’s anti-cruelty laws.[37] On the other hand, following local and national pressure, the Medical College of Wisconsin announced in 2013 that it was ending the use of animals in its instructional program.[38]

As national attitudes toward circuses and zoos as well as laboratory animals have changed and the horse community has shrunken, Milwaukee of the 2010s has riveted its attention on stray and abandoned domestic animals. The WHS has launched a major campaign to cut euthanasia rates for strays, the face of which is Hank the dog. A bichon frise mixed-breed who strayed into the spring training camp of the Milwaukee Brewers in 2014, became the team’s unofficial mascot, and won the Dog of the Year award at the 2014 World Dog Awards, Hank is indeed the region’s newest animal celebrity.[39]

Footnotes [+]

- ^ Charter and Ordinances of the City of Milwaukee, with the Constitution of the State, and Acts of the Legislature Relating to the City (Milwaukee: Daily News Book, 1857), 66-67, 418-421.

- ^ Paul E. Geib, “‘Everything But the Squeal’: The Milwaukee Stockyards and Meat-Packing Industry, 1840-1930,” Wisconsin Magazine of History 78, no. 1 (Autumn 1994): 2-23, esp. 9-10, 19, 23. On the tanning industry, see John Gurda, The Making of Milwaukee (Milwaukee: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 1999), 119-120, 160.

- ^ Kirk Bates, “Milwaukee in the Horse and Buggy Days,” Milwaukee Journal, July 19, 1951; “At Last Milwaukee’s a None Horse Town,” Milwaukee Journal, April 18, 1952.

- ^ Frank A. Flower, History of Milwaukee, Wisconsin: From Prehistoric Times to the Present Date (Chicago: Western Historical Company, 1881), 219.

- ^ Lillian Krueger, “Social Life in Wisconsin: Pre-Territorial through the Mid-Sixties,” The Wisconsin Magazine of History 22, no. 3 (March 1939), 312-328, esp. 321-322; John G. Gregory, History of Milwaukee Wisconsin, vol. 2 (Chicago-Milwaukee: S. J. Clarke Publishing Company, 1931), 1059. See also Erika Janik, “Dashing through the Snow: Sleigh Rides in Wisconsin,” The Wisconsin Magazine of History 92, no. 2 (Winter 2008/2009), 42-49.

- ^ Charter and Ordinances of the City of Milwaukee (1857), 67.

- ^ Gregory, History of Milwaukee, 1059-1061; “Historic Designation Study Report: Cold Spring Park Historic District,” 3-4, accessed June 9, 2015.

- ^ John Gurda, “National Park: Where Milwaukee Went for Thrills 100 Years Ago,” August 9, 2014, Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.

- ^ Sarah Biondich, “Spiritual Uplift at Washington Park,” Washington Park Zoo History, accessed June 9, 2015; Vernon N. Kisling, Jr., “Zoological Gardens of the United States,” in Zoo and Aquarium History: Ancient Animal Collections to Zoological Gardens, ed. Vernon N. Kisling (Boca Raton: CRC Press, 2001), 147-180, esp. 162; Darlene Winter, Elizabeth Frank, and Mary Kazmierczak, Milwaukee County Zoo (Charleston, S.C.: Arcadia Publishing, 2014), 11.

- ^ 150 Years of the Wisconsin State Fair: An Illustrated History, 1851-2001 (West Allis, WI: Wisconsin State Fair Park, 2001), 17, 39, 42, 62; James B. Nelson, “Racing Porkers Give State Fair a Running Start,” Milwaukee Sentinel, July 31, 1987.

- ^ John C. Eastberg, Pabst Farms: The History of a Model Farm (Milwaukee: Pabst Farms, Inc., 2014), 228, 249.

- ^ “Big Horse Show: Milwaukee to Have One Next Year,” Milwaukee Journal, October 11, 1902; “What Horse Show Has Done for Milwaukee, Milwaukee Journal, July 25, 1903.

- ^ Bob Funkhouser, “MGM Spring-Milwaukee Goes to Madison,” The Saddle Horse Report, June 1, 2007, accessed June 9, 2015.

- ^ Jackie Loohauis-Bennett, “Circus Parade Secures Funding, Will Return July 12,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, March 17, 2009. On the parade’s horses, see Herbert Clement and Dominique Jando, The Great Circus Parade (Milwaukee: Gareth Stevens Publishing, 1989), 36-37, 88. For a general history, see C. P. Fox, America’s Great Circus Parade: Its Roots, Its Revival, Its Revelry (Greendale, WI.: Reiman Publications, 1993).

- ^ “Countess Heine, Elephant, Now at Milwaukee’s Zoo,” Milwaukee Journal, August 1, 1907; C. F. Butcher, “Running a ‘Hotel’ for One Thousand Animals and Birds: Milwaukee’s Zoo in Washington Park Started with Elephant 30 Years Ago,” Milwaukee Journal, February 9, 1936; and Cyrus F. Rice, “Potent Potion Fails, Venice Rolls Over and Dies,” Milwaukee Sentinel, June 4, 1953. For Heine’s early years at the zoo, see Winter, Frank, and Kazmierczak, Milwaukee County Zoo, 18-19.

- ^ “Sultana, First Polar Bear to Raise Young in Captivity, Dies at Zoo of Old Age—35,” Milwaukee Journal, April 14, 1947; Winter, Frank, and Kazmierczak, Milwaukee County Zoo, 27, 43.

- ^ Winter, Frank, and Kazmierczak, Milwaukee County Zoo, 10.

- ^ Alicia Armstrong, “Samson Leaves Memories, More,” Milwaukee Journal, November 28, 1981; “Samson Memorial Planned,” Milwaukee Sentinel, November 30, 1981; and “A Giant of a Beast Had His Impact on Humans,” Milwaukee Journal, December 3, 1981. See also Winter, Frank, and Kazmierczak, Milwaukee County Zoo, 50-51, 81.

- ^ Jackie Loohauis, “Lota Had Finally Found Peace: Hard-luck Elephant Dies at Sanctuary,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, February 11, 2005; Joanne Weintraub, “Barker Still a Prize,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, May 9, 2007. See also “In Memory of Lota, 1951-February 9, 2005,” The Elephant Sanctuary, accessed June 9, 2015, https://www.elephants.com/lota/lotaBio.php. Information about Lota has been moved to https://www.elephants.com/elephants/lota, last accessed March 21, 2017.

- ^ John Gurda, Making of Milwaukee, 316.

- ^ Stephen P. Servais, “At the Trail’s Edge: American Indian Occupation of Milwaukee to 1950” (Master’s thesis, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 1998), 10-12, 83.

- ^ Diane M. Buck and Virginia A. Palmer, Outdoor Sculpture in Milwaukee: A Cultural and Historical Guidebook (Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1995), 95-97 (Kosciuszko), 154-156 (von Steuben), 144-146 (Bergh), and 138-139 (“Milwaukee, 1989”). On the Bergh statue, see also Virginia A. Palmer, One Hundred Years of Caring: The Wisconsin Humane Society, 1878-1979 (Milwaukee: Wisconsin Humane Society, 1979), 21-22; “Money, Flexibility Can Provide Suitable Home for Statue,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, September 6, 1999; Jackie Loohauis, “Local Shelter Goes from Dead End to High End,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, December 2, 1999; and “History,” Wisconsin Humane Society, accessed June 9, 2015.

- ^ Buck and Palmer, Outdoor Sculpture, 90-91 (“Animal Friends Memorial Fountain”) and 127-129 (Wolcott).

- ^ Crocker Stephenson, “Taxidermist Goes Ape over Samson’s Image,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, July 11, 2006; “Samson,” Milwaukee Public Museum, accessed June 21, 2015.

- ^ “Lifelike Figure of Gorilla Sambo Will Have a Home in Museum,” Milwaukee Journal, February 6, 1961.

- ^ Charter and Ordinances of the City of Milwaukee (1857), 419; Charter and Ordinances of the City of Milwaukee (Milwaukee: Daily News Book, 1875), 151.

- ^ Palmer, One Hundred Years of Caring, 11; WI Session Laws 1977, 59.877 published July 15, 1977, Assembly Bill 202, accessed June 9, 2015.

- ^ Palmer, One Hundred Years of Caring, 9, 19-20; Virginia A. Palmer, “Lenore H. Cawker, “The Animals’ Friend,” Milwaukee History 2, no. 2 (1979): 43-48.

- ^ Jesse Garza, “Officials Consider Animal Control: Humane Society Will No Longer Shelter Strays,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, February 13, 1996; “Plan for Stray Animal Service Set,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, September 30, 1997; and “Who Is MADACC?,” MADACC, accessed June 9, 2015.

- ^ For a list of Wisconsin’s animal welfare groups, see “Search for Welfare Groups by State: Wisconsin,” Petfinder, accessed June 22, 2015.

- ^ Nan Blake, “In Milwaukee’s Dog Cemetery: Tributes to Animal Friends Who Loved, and So Were Loved,” Milwaukee Sentinel, July 23, 1922; “Told by Sentinel Files,” Milwaukee Sentinel, May 10, 1933.

- ^ Lawrence Sussman, “So Long, and Thanks: Cemetery Here Gives Grief for a Pet the Honor of a Home,” Milwaukee Journal, December 17, 1987. See Pet Lawn Inc., accessed June 9, 2015.

- ^ “Humane Society Dedicates New Pet Cemetery,” MB News 65, no. 1 (January 2008), 18-20, accessed June 23, 2015.

- ^ “Dog Park Could Be on 1 of 22 Proposed County Sites,” Milwaukee Journal, July 20, 1995; Corissa Jansen, “Dog Owners Search for Room to Roam Free from Leash Laws,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, May 31, 2003; “Thefts at Dog Park Put Pet Owners on Watch,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, June 29, 2005; and “Dog Park Sought in Tosa,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, May 1, 2006. See also “Dog Exercise Areas,” Milwaukee County Parks, accessed June 9, 2015.

- ^ “Reward Asked for War Dogs: Two Aldermen to Offer Resolution for License Fee Exemption,” Milwaukee Journal, December 10, 1944.

- ^ “Doctors Admit Dogs Tortured by Vivisection: Assembly Hearing on Blenski Bill Begins,” Milwaukee Sentinel, March 1, 1945; Marie Graves Thompson, “Anti-Vivisection Bill Awakened Wisconsin, Milwaukee Sentinel, June 21, 1945.

- ^ See Section 3539g of the 2011 Wisconsin Act, 2011 Assembly Bill 40, 488, accessed June 9, 2015. For Wisconsin’s complete Chapter 951, “Crimes against Animals,” see Wisconsin-Cruelty-Consolidated Cruelty Statutes, Animal Legal & Historical Center, accessed June 9, 2015.

- ^ Susanne Rust, “Medical College’s Use of Dogs Denounced,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, March 12, 2006; “Wisconsin Medical School Ends Its Last Animal Lab,” Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine, accessed June 9, 2015.

- ^ “Fetch Boy! Stray Dog Becomes Milwaukee Brewers’ Unofficial Mascot after Being Found at Spring Training,” Daily Mail.com, February 24, 2014, accessed June 9, 2015; Adam McCalvy, “Ballpark Pup Has Brewers Celebrating ‘Hanksgiving,’” November 28, 2014, Official Site of the Milwaukee Brewers, accessed June 9, 2015.

For Further Reading

Clement, Herbert, and Dominique Jando. The Great Circus Parade. Milwaukee: Gareth Stevens Publishing, 1989.

Palmer, Virginia A. One Hundred Years of Caring: The Wisconsin Humane Society, 1878-1979. Milwaukee: Wisconsin Humane Society, 1979.

Winter, Darlene, Elizabeth Frank, and Mary Kazmierczak. Milwaukee County Zoo. Charleston, S.C.: Arcadia Publishing, 2014.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.