People have inhabited the geographic area that is the scope of this encyclopedia, what we now call the Milwaukee Metropolitan Area, for many millennia. Burial mounds, once quite common, but now mostly covered or leveled by later inhabitants, provide archaeological testimony to the thousands of years of human life in the area. The mound builders were non-literate, migratory, hunter-gatherer peoples, ancestors of the Indian tribes that the first European explorers met when they explored the North American continent in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Those tribes were also non-literate, semi-sedentary societies, from several linguistic and cultural origins, even before Europeans began to disrupt tribal life and integrate the native communities into the long-range trade of the emerging globally-connected world.

What we know about the past in the Great Lakes region, upper Midwest, and local area as these European-Indian encounters began and the place that became Milwaukee began to come into focus, comes from the oral traditions of the tribes, the archaeological record, and the written records of the Europeans. It’s a foggy past indeed, filled with gaps, myths, and biases but does provide something of a starting point for understanding Milwaukee’s demographic past.

The obvious “finding” of this historical record is that humans in the past visited, camped, and found resources in what would become the city of Milwaukee because of the confluence of lake and river, and the bounty of wildlife, fish, wild grains, fruits and berries, and other natural resources that could sustain them. By the time of the European encounter, the native peoples also cultivated food, particularly corn and squash, though not in the way of permanent “farms” of later years. Settlements were small and transitory; communities moved with the seasons to hunt and fish over the year.

The arrival of Europeans, in this part of the world, the arrival of French explorers and the settlement of what became Montreal in the seventeenth century, transformed the lives of the native peoples in the Milwaukee area. Montreal, almost 1,200 kilometers (more than 700 miles) from Milwaukee as the crow flies, became the hub of the upper Great Lakes fur trade, as Europeans went on a buying frenzy for beaver hats, and French traders found that Indians could supply beaver pelts and would “sell” them for “trade goods,” particularly metal products, guns, beads, and alcohol.

The trade network “highway” was a seasonal, water-based route that primarily ran from Montreal and the St. Lawrence River to the Great Lakes and reached settlements in what would become Michigan and Wisconsin at Mackinac and Green Bay. The Milwaukee area was initially quite far from this river- and lake-based trade network, but as the fur trade spread in the later seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and French explorers and missionaries traveled further inland to identify additional sources of furs and perhaps a route between the Great Lakes and the Mississippi River, they visited the Milwaukee area while exploring the Western shore of Lake Michigan.

By the end of the eighteenth century, French trader Jacques Vieau founded what would become a permanent trading post at the site that would become Milwaukee. His son-in-law, Solomon Juneau, would continue the trade, and become the founder and first mayor of Milwaukee in 1846.

During the last half of the eighteenth century and much of the first half of the nineteenth, the basic trading economy of French traders and Indian hunters shaped the land use and settlement patterns of most of what would become Wisconsin. Nevertheless, for much of that period, global wars among European powers, the Seven Years War or French and Indian War (1757-1763), the American Revolutionary War (1776-1783), and the War of 1812 (1812-1815) also shifted the political authority, from the Euro-American point of view, of who “owned” the lands that encompassed Milwaukee and Wisconsin. Indian tribal communities throughout the Great Lakes region were also drawn into the wars to support or oppose one power or another.

The actual fighting took place far from Milwaukee, but the war settlements eventually profoundly affected later economic and demographic development of Milwaukee and Wisconsin. The French lost the Seven Years War and ceded Canada to the British crown. The British lost the American Revolution and ceded substantial portions of Canada—for our purposes, the areas in the upper Great Lakes—to the United States. These lands became part of the Northwest Territory in 1787, envisioned once settled to become new states of the United States. The War of 1812 confirmed continued American legal control of the region. In practice, Wisconsin remained unceded Indian land with a fur trading economy.

American political and military penetration of the Western Great Lakes was quite minimal until the 1820s and 1830s, and almost non-existent in the Milwaukee area. Americans garrisoned frontier forts located at existing trading posts to assert military control of the area that would become Illinois and later Wisconsin: Fort Dearborn (future Chicago); Fort Howard (at Green Bay); Fort Crawford (Prairie du Chien). There was no fort at Milwaukee. The Northwest Territory was carved into new states and territories, starting with Ohio’s admission to the union in 1803. Wisconsin was made part of Indiana Territory (1800), Illinois Territory (1809) and finally Michigan territory in 1818; and became a territory of its own in 1836 when Michigan became a state. “Government” such as it was, was far away, in Detroit, for example, for the years when Wisconsin was part of Michigan Territory.[1]

East of Lake Michigan, American settlers established freehold farms, pushing the Indian tribes west, amid repeated Indian wars. Close to the Mississippi River, Euro American migrants established lead mining communities. The Black Hawk War of the early 1830s, fought in northwestern Illinois and what is now southwestern Wisconsin, effectively ended the existing Indian way of life in the Wisconsin region. Indian land cessions in 1831 and 1833 made it possible for Americans to put land that is now the Milwaukee area up for sale. Frenzied lot platting and sales took place in the mid-1830s; the land boom collapsed in the Panic of 1837. But the die was cast; the lands available for hunting and trapping became the property of men planting farms or businesses. Solomon Juneau learned English, became a U.S. citizen (1831), filed claims to the land that would become Milwaukee north of the central marsh and east of the Milwaukee River, and became the city’s first mayor when the territorial legislature approved a city charter in 1846. A surge of in-migrants followed which would change the nature of Milwaukee and Wisconsin forever.

Until the 1830s, reflecting the economy and settlement patterns of the fur trading and mining eras, the communities of territorial Wisconsin with Euro-American populations were small, and far away from Milwaukee. The first effort at measurement was a territorial census in 1836, which counted Euro Americans but not Indians. The count reported under 12,000 people. The Indian population at the time was more than twice that, though estimates are difficult, likely 24,000 in 1827. Fewer than 3,000 Euro-Americans were counted in “Milwaukee County” which also included present day Racine and Kenosha counties. The most populous Euro-American area of the territory was Iowa County, the lead region, with over 5,000 people.[2]

By 1850, the first federal census after the incorporation of the city of Milwaukee and statehood for Wisconsin counted some 300,000 people in Wisconsin and 20,000 in the city. The count for the area encompassing the current counties of Milwaukee, Ozaukee, Washington, Waukesha, Racine, Kenosha, and Walworth (Milwaukee and its hinterland) was 113,000, or about 37 percent of the state population. By 1890, the city of Milwaukee boasted a population of about 200,000; Wisconsin almost 1.7 million; and the seven-county Milwaukee core and hinterland, almost 387,000. In other words, city and countryside were settled at the same time, both areas receiving similar migrant streams.[3]

The migrants were Americans from the east (the Yankee-Yorkers) and European immigrants, including from the British Isles, the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, and Scandinavia. But mostly the immigrants to Milwaukee came from the German-speaking areas, making the city in particular the Deutsch Athen. By 1880, as migrants continued to arrive, the census reported that half of the population in today’s four-county metro area was born in Wisconsin. The population was young; the median age was about 20. The census also reported that 58 percent of Milwaukee County residents had a father born in Germany. In Ozaukee County, 61 percent of the residents reported their father was born in Germany; in Washington County 72 percent of the residents reported a German-born father. Only Waukesha County showed a different pattern. There, 33 percent of the residents had a German-born father; another 31 percent reported a father born in England, Ireland, Scotland, or Wales.

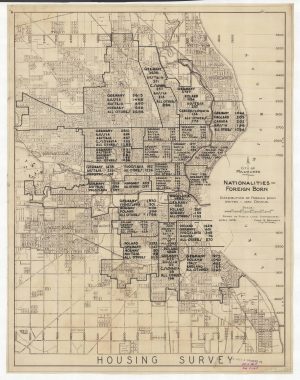

After 1880, Milwaukee’s migrant streams expanded to include Eastern Europeans, including Poles, many smaller communities of Slavs from the empires of Europe, European Jews, and peoples from the Mediterranean lands, including Greeks, Italians, and Syrians. In 1920, just before the U.S. ended its open immigration policy, 22% of the population of the metro area was foreign born. An additional 45% of the population had at least one foreign-born parent.

If Milwaukeeans of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century could feel like they were living in a set of transplanted European communities, most people did not reside in communities like the worlds they had left behind. The city was a hub of commerce, trade, and increasingly manufacturing; the countryside of freehold family farms particularly specializing in dairy.

Milwaukee’s economic and demographic life was also profoundly affected by the phenomenal expansion of Chicago to its south. Chicago and its immediate hinterland also grew from the mid-nineteenth century onward. But Chicago exploded into the second largest city in the country in 1890, when its population topped one million and became the transportation and commercial hub of the Midwest. In the first decade of the twentieth century, the population of metropolitan Chicago outpaced the population of the entire state of Wisconsin.

Milwaukee continued to grow as well, surpassing a half a million people by 1930, as the nation’s twelfth largest city.[4]

Milwaukee’s manufacturing sector expanded even more, particularly for machinery and the metal trades, along with food processing and leather tanning. Immigration restriction in 1924 and then the Great Depression of the 1930s stopped both migrant streams from abroad and robust in-migration from rural America. The city experienced unemployment rates approaching 50 percent of the workforce in the mid-1930s. The city grew by fewer than 10,000 people from 1930 to 1940.

Two world wars with Germany in the first half of the twentieth century also dramatically affected the ethnic and demographic character of the region. Defining the city as the Deutsch Athen became a liability if things German came to represent support for a militarized enemy nation. National Prohibition temporarily closed the city’s famed German-style beer industry. In this environment “Americanization” campaigns pressured children and grandchildren of all immigrants to speak English, drop “foreign” ways, and identify with “American,” more specifically “white American” life.

Then the city and nation experienced an economic boom during World War II, and the area’s manufacturing sector became a vital contributor to the “arsenal of democracy.” Labor demand again exploded; the metropolitan area population grew by 100,000 people between 1940 and 1950.

The sources of the growth shifted once again. The war and restrictive national immigration law prevented an influx of foreign immigrants, though Milwaukee saw its share of international refugee migrants from the late 1940s on. Once again, though, new migrant streams emerged.

During the 1920s, Milwaukee had seen the birth of a small black working class as southern-born African Americans came to the city.[5] The Depression slowed that flow, but it surged again during the war years and developed into the “late Great Migration” that lifted Milwaukee’s black community from one percent of the city’s population in 1930 to 40 percent in the early 21st century.[6] A similar, smaller, migration of Latinos to the area began at the same time, so that by the twenty-first century the combined communities of Black, Latino, and Asian people of color make up a majority of the city’s population.

At the same time, a “baby boom” from the late 1940s into the 1960s affected all communities, helping to boost the metro area’s population from one million in 1950 to 1.4 million in 1970. The most urban portions of the metro area spread out from the late 1940s onward. The city annexed large areas of unincorporated land in Milwaukee County, doubling the size of the city to 96 square miles, while reducing the population density from about 13,000 persons per square mile in the 1940s to 6,500 per square mile in 1990. Suburban style development sprouted in both the city and county proper, and in the towns, villages, and farmland of the outlying counties.[7]

All this was easy enough to see as it happened. However, while it is not too difficult to chart the migration and growth of newly arriving communities, it is a bit more difficult to reconstruct the demographic and ethnic changes in established ones as they are affected by what demographers call the patterns of fertility and mortality, as well as migration and cultural assimilation. The headline news of the “black migration” and “white flight” in the city captured the broad patterns and can be enriched with information on the kinds of families and households that moved.

As the city approached its centennial in 1946, census results reported the median age of Milwaukeeans was older. In all four counties in the metro area, the median age was around 31 or 32 in 1950, as life expectancy rose, and before the baby boom was in full force. By 1970, the median age in the three collar counties around Milwaukee had dropped to 25 as the suburbs grew and filled with young families. Throughout the twentieth century the population of those collar counties was overwhelmingly white, descendants of the farming communities that settled the area in the nineteenth century, now augmented by the descendants of city dwellers moving to the new subdivisions. The new communities were similar in ethnic background to those of the smaller existing communities. Northside Milwaukeeans moving to Germantown were likely to find the restaurants and Lutheran and Catholic churches that were similar to those in the old neighborhoods.

Meanwhile, the city became the home of people of color occupying the housing available as the new suburbanites left. Milwaukee had always been a city of ethnic enclaves, with Germans clustering on the North Side, Poles on the South, Italians in the Third Ward. The process of ethnic transition was not a smooth one for the post World War II minorities. In the 1950s and 1960s, the civil rights movement demanded equal access to housing, jobs, and services, particularly in public education, regardless of race or ethnic background. Local government, real estate interests, and existing homeowners resisted opening up the existing housing stock to the rapidly growing black and Latino communities, and patterns of extreme residential racial and ethnic segregation arguably became the most notable demographic characteristic of the four county area.

The patterns for Milwaukee County are revealing. In the 1950s, the county population grew 19 percent, from about 870,000 in 1950 to 1.036 million in 1960. Of that growth, 150,000 was what demographers call “natural increase,” the surplus of births over deaths. An additional 15,000 was “net migration,” the surplus of in-migrants over out-migrants. The overall numbers mask the racial differences. In fact, that “net migration” was composed of net in-migration of about 27,000 African Americans and out-migration of 12,000 whites. Blacks moved in faster than whites moved out and faced housing discrimination and crowding into neighborhoods bursting at the seams.

These patterns accelerated in later decades. Milwaukee County population peaked at 1.054 million in 1970, as the baby boom and black migration continued, despite the fact that white net migration was negative, estimated at 127,000 in the 1960s. Once the baby boom ended in the 1960s, and white net out-migration continued (almost 185,000 in the 1970s), the county population dropped and stabilized, ranging from 965,000 in 1980 to about 948,000 in 2010. Some time after the 1970s, black net in-migration also stopped, and reversed. In the 1990s and 2000s, the county experienced black negative net migration, while new streams of growing Latino and Asians produced patterns of positive net in-migration and were the only communities that buoyed the population of the county.[8]

Meanwhile, the last thirty years of the twentieth century saw major challenges to the regional manufacturing economy. From the late nineteenth century through the middle twentieth century, arguably manufacturing was the economic lifeblood of the region, and the success of that production economy in turn supported the livelihoods of both long-term residents and new in-migrants. When that economy faltered because of global competition, or found efficiencies that reduced the need for labor, the peoples of Milwaukee found themselves in competition for fewer jobs. Iconic firms closed or moved out of the area. Once again, Milwaukeeans saw their economic world upended as the storied high wage industrial economy that had drawn in so many migrants over the previous century disappeared.

The Milwaukee region was not alone in facing this economic dislocation, what came to be called “deindustrialization.” Nevertheless a spirited debate opened locally over whether the economic dislocation was anyone’s fault, and what to do about it. Analysts from differing political stripes pointed fingers at inept managers, selfish investors, unrealistic union demands, and lazy or under-educated job seekers. They proposed solutions ranging from redevelopment of abandoned industrial zones, to reform of local educational systems, to finding new service industries to replace the declining manufacturing base, to cutting wages and union rules to make local companies more profitable.[9]

Though no section of the region was immune, the economic dislocation fell most heavily on the minority communities that were just securing a stable toehold in the area. Since the overwhelming proportion of the region’s minorities lived in the city, poverty and other indicators of economic crisis went up.[10] Economic dislocation exacerbated the existing patterns of discrimination in housing and education and left the city and the surrounding suburbs taking different approaches to redevelopment. Suburbanization of both housing and business into “greenfield” areas of the metropolitan area continued while the city pursued “brownfield” redevelopment of old industrial sites and downtown redevelopment.[11] Even some older suburbs pressed for redevelopment and denser housing.

Twenty-first century metropolitan Milwaukee displays local areas with sharp demographic distinctions, in a region where population growth slowed compared to long term trends. Population growth in the four county area since 1980 has been modest, increasing from 1.44 million to 1.56 million in 2010, and all of it outside the city of Milwaukee. The city declined from its 1960 peak of 747,000, when it was 58 percent of the four-county population. It has hovered around 600,000 since the 1990s, about 38 percent of the metro area population. Even in the city, the population has spread out. In the smaller city population of 2010, there were 229,000 households; there were about 230,000 households in the city in 1960. The city has become “majority minority,” and, if anything, continues the patterns of migration, ethnic and racial churn, and social diversity of the past 150 years. The three “WOW” or collar counties (Waukesha, Ozaukee, and Washington) display population growth, and net in-migration from Milwaukee County, but in other respects do not display patterns that are very different from the city. Household size in 2010 in Ozaukee, Washington, and Waukesha counties was 2.47, 2.53 and 2.52 respectively. In Milwaukee County it was 2.41, and the city was 2.38. Fertility rates for all four counties are below replacement level. The big difference between the city and Milwaukee County is that the WOW county populations are overwhelmingly white and more politically conservative.

Footnotes [+]

- ^ Robert Nesbit, revised and updated by William F. Thompson, Wisconsin: A History, 2nd ed. (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1989), 118-132, particularly 124.

- ^ Nesbit, Wisconsin, 80, 92.

- ^ Southeastern Wisconsin Regional Planning Commission, The Population of Southeastern Wisconsin, Technical Report No. 11, 5th ed. (Waukesha, WI: SWRPC, 2013), 7. Unless otherwise identified, census tabulations are calculated from Steven Ruggles, Katie Genadek, Ronald Goeken, Josiah Grover, and Matthew Sobek. Integrated Public Use Microdata Series: Version 7.0 [dataset]. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, 2017. https://doi.org/10.18128/D010.V7.0.

- ^ U.S. Census Bureau, “Population of the 100 Largest Urban Places: 1930,” https://www.census.gov/population/www/documentation/twps0027/tab16.txt, accessed January 15, 2018; the city was the 13th largest in 1940, U.S. Census Bureau, “Population of the 100 Largest Urban Places: 1940,” https://www.census.gov/population/www/documentation/twps0027/tab17.txt.

- ^ Joe William Trotter, Jr., Black Milwaukee: The Making of an Industrial Proletariat, 1915-45 (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1985, 2006).

- ^ Paul Geib, “The Late Great Migration: A Case Study of Southern Black Migration to Milwaukee, 1940-1970.” Master’s thesis, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 1993.

- ^ Well into the 1970s, the Wisconsin and Milwaukee economies were touted as healthy and prosperous. See for example, Paul Ingrassia, “Star of Snow Belt: Despite Cold Weather, High Taxes, Wisconsin Keeps Luring People Its Quality of Life Offsets Attraction of Sun Belt,” Wall Street Journal, September 16, 1977, 1. The headline continued by noted that “Business-Tax Cuts Help Beer, Brandy and Sausages Star of Snow Belt: Despite the Cold, Wisconsin Keeps On Luring People.”

- ^ SWRPC, “The Population of Southeastern Wisconsin”; see also the tabulations from Richelle Winkler, Kenneth M. Johnson, Cheng Cheng, Jim Beaudoin, Paul R. Voss, and Katherine J. Curtis, “Age-Specific Net Migration Estimates for US Counties, 1950-2010,” Applied Population Laboratory, University of Wisconsin- Madison, 2013. Web. [January 2018] < http://www.netmigration.wisc.edu/> which permit calculation of detailed patterns by county for the nation from 1950 to 2010.

- ^ See for example, Margo Anderson, “Epilogue, Milwaukee’s Usable Past,” in Perspectives on Milwaukee’s Past, Margo Anderson and Victor Greene, eds. (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2009), 317-29; George Lightbourn and Sammis White, “Moving the Milwaukee Economy Forward: The Five Steps Necessary for Success,” Wisconsin Policy Research Institute Report, v. 21, no 3, May 2008, accessed January 16, 2018.

- ^ Marc V. Levine, “The Crisis of Black Male Joblessness in Milwaukee: Trends, Explanations, and Policy Options,” University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Center for Economic Development Working Paper, March 2007, accessed January 15, 2018.

- ^ Colin Woodard, “How Milwaukee Shook Off the Rust,” Politico, August 18, 2016, accessed January 16, 2018.

For Further Reading

Anderson, Margo, and Victor Greene, eds. Perspectives on Milwaukee’s Past. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2009.

Southeastern Wisconsin Regional Planning Commission, The Population of Southeastern Wisconsin, Technical Report No. 11 (5th ed.). Waukesha, WI: SWRPC, 2013.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.