Operating from 1847 to 1999, the Allis-Chalmers Corporation was one of Milwaukee’s key manufacturing giants and for a time the city’s largest employer, producing what one historian describes as “the ‘big stuff’ for America’s expanding urban and industrial markets.”[1]

Allis-Chalmers originated in James Seville and Charles Decker’s Reliance Works, a pioneer iron foundry and machine shop established on West Water Street (now North Plankinton Avenue) in 1847.[2] A major regional supplier of milling equipment, the Reliance Works declined into bankruptcy when its chief customers, the lumber and flour industries, struggled during the Panic of 1857.[3] Early Milwaukee tanning magnate, Edward Phelps Allis, purchased the firm at a sheriff’s sale in 1861, forming the Edward P. Allis & Company Reliance Works.[4] In 1867, the company moved to a larger site in Walker’s Point to facilitate the manufacture of new steam-powered machines.[5] In 1869, Allis & Co. purchased its largest local competitor, the nearby Bay State Iron Manufacturing Company, allowing it to introduce new products, including portable mills, boilers, and gearing.[6] In the early 1870s, Allis & Co. added a pipe foundry, supplying large pipes and pumps for Milwaukee’s new lake-fed water system.[7]

Allis & Co. continued to innovate in saw mills and grain processing equipment throughout the late nineteenth century. It expanded production to other large machines, including mining hoists and pumps, blowing engines and rollers for the steel industry, and pumps and electricity generators for major American cities.[8] By the turn of the century, Allis & Co. had become the “largest single manufacturer of steam engines in the United States.”[9] In the process, the company also became one of the city’s largest employers, growing from 200 workers in 1871, to nearly 1,500 in 1889, and 1,800 in 1900.[10]

Untrained in metalworking and mechanics, E. P. Allis focused primarily on the company’s finances and contracts, relying on the expertise of notable engineers, such as steam engine designer Edwin Reynolds.[11] Allis was not unreceptive to workers’ demands at the Reliance Works, matching employee contributions to a new Allis Mutual Aid Society in 1883 and offering an eight-hour agreement prior to the strikes of May 1886.[12]

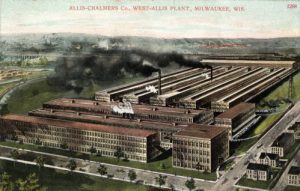

Reynolds took over the company’s leadership after Allis’ death in 1889 and initiated plans for its modernization. In 1901, Allis & Co. merged with three other major machinery manufacturers—the Chicago-based Fraser-Chalmers Company and Gates Iron Works, and the Scranton-based Dickson Manufacturing Company—forming the Allis-Chalmers Company. The following year Allis-Chalmers opened an enormous new plant along major rail lines on the western outskirts of Milwaukee, creating the industrial suburb of West Allis.[13]

In the early 1900s, Allis-Chalmers began producing gas engines for industrial machinery, becoming “the largest builder of gas engines in the United States.”[14] In 1904, the company acquired the Cincinnati-based Bullock Electric Manufacturing Company, bolstering its production of generators, motors, transformers, and other electrical products.[15] With these additions, Allis-Chalmers operated major plants in Milwaukee, Chicago, Scranton, and Cincinnati, while boasting its mastery over “four powers: steam, gas, water, electricity.” By late February 1916, there were over 5,500 workers employed in West Allis within a total corporate workforce of 8,300.[16]

Allis-Chalmers further expanded its interests in the 1910s by establishing a new tractor division. Acquiring the Monarch Tractor Corporation and the La Crosse Plow Company, Allis-Chalmers became a leading national manufacturer of agricultural machinery by the 1930s.[17]

A diverse array of product divisions made Allis-Chalmers particularly well suited for securing major government contracts. For instance, the Public Works Administration ordered seven hydraulic turbines from Allis-Chalmers for its Hoover Dam project in the late 1930s.[18] During the First and Second World Wars, the company produced engines, gun systems, and electrical controls for ships, aircraft engine components, shells, and tracked vehicles.[19] Allis-Chalmers also produced uranium-processing and research equipment for the Manhattan Project.[20]

The West Allis works employed 9,681 workers in 1937, as many as 20,000 during the Second World War, and around 15,000 in the years after the war.[21] The CIO-affiliated UAW Local 248 formed in 1937 to improve wages, hours, and conditions for these workers. However, alleged connections of several union organizers to the Communist Party and a series of extensive, volatile strikes during the Red Scare of the late 1940s drew Congressional intervention and the indictment of union president, Harold Christoffel, for perjured testimony in federal hearings.[22]

Through the mid to late twentieth century, Allis-Chalmers continued to acquire national competitors and expanded into the production of atomic energy and construction equipment. The company reorganized as the Allis-Chalmers Corporation in 1971 to incorporate new global subsidiaries.[23] However, the company struggled to remain competitive as the recession of the early 1980s diminished sales, and other firms surpassed them in global markets. Although Allis-Chalmers attempted to stay afloat by selling product divisions, closing plants, and laying-off workers, the former giant rapidly dwindled—declaring bankruptcy in 1987 and closing its last Milwaukee office in 1999.[24] Much of the old West Allis works was razed or repurposed for retail spaces, offices, and facilities for the Milwaukee Area Technical College in the 1980s and 1990s.[25]

Footnotes [+]

- ^ Stephen Meyer, “Stalin over Wisconsin”: The Making and Unmaking of Militant Unionism, 1900-1950 (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1992), 18, 230. This entry was initially posted on September 29, 2017; a corrected version was posted on July 15, 2019.

- ^ Walter F. Peterson, An Industrial Heritage: Allis-Chalmers Corporation (Milwaukee: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 1976), 7; John G. Gregory, History of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, vol. 1 (Chicago and Milwaukee: S.J. Clarke Publishing, 1931), 545.

- ^ Margaret Walsh, The Manufacturing Frontier: Pioneer Industry in Antebellum Wisconsin 1830-1860 (Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1972), 205-207; Peterson, An Industrial Heritage, 7.

- ^ Peterson, An Industrial Heritage, 1, 7.

- ^ Peterson, An Industrial Heritage,, 9.

- ^ Peterson, An Industrial Heritage; Meyer, “Stalin Over Wisconsin,” 17.

- ^ Peterson, An Industrial Heritage, 10-14.

- ^ Peterson, An Industrial Heritage, 19-95.

- ^ Peterson, An Industrial Heritage, 102.

- ^ Peterson, An Industrial Heritage, 9, 62; Meyer, “Stalin Over Wisconsin,” 17-18.

- ^ Peterson, An Industrial Heritage, 19-63.

- ^ Peterson, An Industrial Heritage, 76-83.

- ^ Peterson, An Industrial Heritage, 102; John Gurda, The Making of Milwaukee (Milwaukee: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 1999), 164; Meyer, “Stalin Over Wisconsin,” 18.

- ^ Peterson, An Industrial Heritage, 125-126.

- ^ Peterson, An Industrial Heritage, 129-131; Meyer, 19.

- ^ Peterson, An Industrial Heritage, 131-32, 174-75; Gurda, Making of Milwaukee, 164-65.

- ^ Meyer, “Stalin over Wisconsin,” 20-21; Gurda, Making of Milwaukee, 242.

- ^ Peterson, An Industrial Heritage, 307.

- ^ Peterson, An Industrial Heritage, 169-175, 330-339; Gurda, Making of Milwaukee, 240, 308.

- ^ Peterson, An Industrial Heritage, 339-341; Gurda, Making of Milwaukee, 308-310, 312.

- ^ Peterson, An Industrial Heritage, 307; Gurda, Making of Milwaukee, 308, 377.

- ^ Gurda, Making of Milwaukee, 324.

- ^ Peterson, An Industrial Heritage, 348-352; C. Edward Weber, “Epilogue: Fighting Takeover, Turnaround Strategy,” in Peterson, An Industrial Heritage, 397-405.

- ^ Meyer, “Stalin over Wisconsin,” 229-230; Gurda, Making of Milwaukee, 377, 418; Ray Kenney, “Allis-Chalmers Foundering,” Milwaukee Journal, June 29, 1987, 1A, 4A.

- ^ Meyer, “Stalin over Wisconsin,” 230; Gurda, Making of Milwaukee, 377, 418; Gretchen Schuldt and Cary Spivak, “MATC May Have to Gut Building,” Milwaukee Sentinel, April 19, 1991, sec. 1, 1, 15.

For Further Reading

Meyer, Stephen. “Stalin over Wisconsin”: The Making and Unmaking of Militant Unionism, 1900-1950. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1992.

Peterson, Walter F. An Industrial Heritage: Allis-Chalmers Corporation. Milwaukee, Allis-Chalmers Corporation, 1978.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.