Several distinct phases in land use and planning are apparent throughout Milwaukee’s history. Informal and “special purpose” planning dominated the city’s early decades, followed in the Progressive Era by creation of formal planning bodies that guided growth and redevelopment for the first half of the twentieth century. Lastly, attempts at both regional planning and central city redevelopment embodied the last half of the twentieth and the early twenty-first centuries.

Milwaukee’s early decades yielded land use patterns consistent with a growing nineteenth century frontier city. Three separate settlements—Juneautown, Kilbourntown, and Walker’s Point—merged to form the city of Milwaukee in 1846. All three settlements had sprouted up near the confluence of the Milwaukee and Menomonee rivers. Early Milwaukee’s growth continued along both, with warehouses, factories, and other businesses using the rivers’ access to Lake Michigan to export goods. As industry expanded along the city’s main railroad lines, thousands of homes were built astride grid-platted streets radiating north, west, and south from the original settlements. As Milwaukee’s population grew rapidly after the Civil War, a variety of problems emerged. City residents realized they required some form of planning and public services to resolve. To combat frequent outbreaks of contagious diseases, city residents formed the Milwaukee Board of Health in 1867. Eleven years later, it was reorganized into the Milwaukee Health Commission, putting Milwaukee on the national forefront of urban public health planning. In 1871, the Milwaukee Water Commission came into existence to extend water lines more efficiently throughout an expanding city. And as the city grew and green space became scarcer, a park board was established in 1890, tasked with acquiring land to preserve spatial respites for local residents.[1]

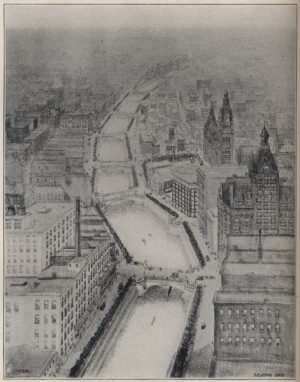

These early efforts to manage the city’s land use reflected narrow goals and are examples of nineteenth century “special purpose planning.” In the early twentieth century, as Milwaukee continued to fill with new residents from the United States, Europe, and Latin America, overcrowding became a major concern. A diverse array of reformers during the Progressive Era began to embrace citywide planning as a holistic exercise. In Milwaukee, the two men most responsible for embracing city planning were architect Alfred Clas and florist Charles Whitnall. Clas was an original member of the Metropolitan Park Commission, created by the Common Council in 1907 to formalize city planning, and he issued the commission’s first major report in 1909. Clas’s plan centered upon a new civic center for Milwaukee, situated on the western edge of downtown and featuring neoclassical buildings reflective of the “City Beautiful” movement’s preferred architectural style with wider city streets radiating out from these structures. Clas also called for redeveloping spaces along the city’s rivers, replete with pedestrian walkways and shade trees, echoing many European cities’ “riverwalks.” Clas’s riverwalk idea was initially stillborn, but the Common Council adopted his civic center plans, widening Kilbourn Avenue and eventually building out the civic center, with the Milwaukee County Courthouse as its most prominent feature.[2]

The second early planning reformer of note, Charles Whitnall, was a member of Milwaukee’s Social Democratic Party. Whitnall and many of his fellow socialists emphasized planning as crucial tool to social reform. Whitnall served on both city and county park commissions (the Milwaukee County Park Commission was created in 1907). In 1923, he authored the report that served as the blueprint for Milwaukee County’s park system. Milwaukee’s era of Socialist governance also included the creation of the city’s first comprehensive zoning ordinance in 1920 and construction of the Garden Homes during the 1920s, one of the first publicly-funded housing projects in the United States.[3] Over the course of the Great Depression, Milwaukee’s planning reputation was enhanced when it was chosen as the site of the federally-planned “Greenbelt” towns, with Greendale constructed as a master-planned community along planning principles similar to those of Whitnall.

As the twentieth century progressed, Milwaukee’s population growth levelled off. With urban development dramatically slowed by the Great Depression, the attention of urban planners shifted toward encouraging instead of managing growth. The 1948 Corporation, later renamed the Greater Milwaukee Committee, successfully convinced city residents to borrow money for a host of downtown projects designed to increase Milwaukee’s prestige as a cultural center. Federal urban renewal laws also increased the focus on redevelopment and slum clearance. In 1958, the city of Milwaukee created its first official Redevelopment Authority, primarily charged with eliminating blighted conditions in city neighborhoods. Urban renewal in the postwar years became synonymous with the destruction of historic neighborhoods and buildings, and the displacement of thousands of poor and nonwhite residents from the city’s “inner core.” The Frank Zeidler administration had hoped to offset slum clearance with political annexation and possibly even metropolitan government, but neighboring suburbs blocked the city’s attempts to grow and unify the county into a single municipality. Realizing more intergovernmental cooperation in planning was badly needed, state legislation created the Southeastern Wisconsin Regional Planning Commission (SEWRPC) in 1960. This became the official planning agency for Milwaukee and six other nearby counties in the region. SEWRPC’s planning focus included highways, transit, sewage, water, and open spaces.[4]

Toward the end of the twentieth century, a clear backlash against slum clearance and the top-down focus of urban renewal emerged. This resistance was centered in by “New Urbanism,” a national design movement that embraced high density, traditional neighborhoods, pedestrian-oriented development, and mass transit. John Norquist, who served as mayor of Milwaukee from 1988 to 2003, was an outspoken advocate of New Urbanism. During his administration, a marked shift in planning took place. In 1999, persuaded by Norquist and his allies, the Milwaukee County Board voted to tear down the one-mile Park East freeway that ran from downtown to the city’s near East Side. Alfred Clas’s long-forgotten plans for walkways along the city’s rivers were revived by the Milwaukee Common Council in 1988, and over the ensuing decades, a Milwaukee RiverWalk was constructed. A protracted battle to create a citywide light rail transit system ended in defeat for rail advocates, but a compromise with state legislators resulted in the planning of a downtown streetcar in the early twenty-first century. As the region’s population continues to expand and sprawl remains a concern, planning in Milwaukee has returned once again to managing growth judiciously, similar to what reformers had hoped for one hundred years ago.[5]

Footnotes [+]

- ^ Bayrd Still, Milwaukee: The History of a City (Madison, WI: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1948), 362, 376, 385. For more on water service provision, see Roger Simon, The City-Building Process: Housing and Services in New Milwaukee Neighborhoods, 1880-1910 (Philadelphia, PA: American Philosophical Society, 1996), chapter 4, and on the politics of water service in the 1900-1920 period, see Kate Foss-Mollan, Hard Water: Politics and Water Supply in Milwaukee, 1870-1995 (West Lafayette, IN: Purdue University Press, 2001), 80-89.

- ^ Alfred Clas, “First Tentative Report,” Metropolitan Park Commission, January 28, 1909, Legislative Reference Bureau, Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

- ^ For Garden Homes, see David Barry Cady, “The Influence of the Garden City Ideal on American Housing and Planning Reform, 1900-1940,” (Ph.D. diss., University of Wisconsin, 1970), and for parkways, see Charles Whitnall, The First Plans for a Parkway System for Milwaukee County, First Annual Report of the Milwaukee County Regional Planning Department, 1924, Milwaukee Public Library.

- ^ For urban renewal in the 1950s, see George Saffraan, “Blight Elimination and Prevention: A Study of Milwaukee’s Blight Elimination and Prevention Process,” prepared for Mayor Frank Zeidler, 1954, Milwaukee Public Library, and on regionalism and its struggles, see Henry Schmandt, The Milwaukee Metropolitan Study Commission (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1965).

- ^ Leila Saboori, “New Urbanism as Redevelopment Scheme: New Urbanism’s Role in Revitalization of Downtown Milwaukee” (MA thesis, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2013).

For Further Reading

Alanen, Arnold R., and Joseph A. Eden. Main Street Ready Made: The New Deal Community of Greendale. Madison, WI: State Historical Society of Wisconsin Press, 1987.

McCarthy, John M. Making Milwaukee Mightier: Planning and the Politics of Growth, 1910-1960. De Kalb, IL: Northern Illinois University Press, 2009.

Norquist, John. The Wealth of Cities: Revitalizing the Centers of American Life. New York, NY: Basic Books, 1999.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.