Roman Catholicism has been an important social and cultural force in the history of Milwaukee from the putative beginnings of white settlement in the area with Solomon Juneau. Juneau himself and his wife, Josette Vieau Juneau, were Catholics. Father Florimond Bonduel, an itinerant priest from Belgium, celebrated the Catholic Mass in their home. From this episodic beginning, Catholics have become a very large and active force locally. As of early 2017, there were over 105,000 Catholics in the city and Catholic property therein (some owned by parishes and others owned by the administrative unit that governs local Catholic life, the Archdiocese of Milwaukee) amounted to nearly $900 million in value (land, property, buildings). The urban presence of Catholics was once very high. However, suburbanization, “white flight,” and deindustrialization have eroded a ubiquitous Catholic presence in Milwaukee.

Catholicism is first and foremost a transnational religious system that embraces an international communion of believers headed by the Bishop of Rome, the pope. Milwaukee Catholics are part of this international network and a small part of the one billion followers of Catholicism on this planet. Catholicism is growing rapidly in Africa, Asia, and parts of Latin America, but it is declining in the western world, including the United States. The Catholic Church is hierarchical in nature, being centrally governed by the pope and his bureaucracy (the curia). But it also is highly decentralized by the subdivision of the Catholic world into quasi-independent jurisdictions called archdioceses or dioceses—the former generally being the headquarters located in a state’s or nation’s largest urban center. The local head of the church is the archbishop or bishop who functions as a spiritual leader, but also as the administrative and legal head of Catholic life.

Milwaukee has been the seat of a diocese since 1843 and an archdiocese since 1875. The archbishops of Milwaukee have exercised considerable influence over Catholic life through the creation of local churches called parishes. Each parish has, at a minimum, a worship site and often a school, along with residences for the clergy as well as the religious sisters who teach in these schools. Many parishes initially had urban boundaries that claimed the allegiance and support of Catholics living within its jurisdiction. Other parishes were created for specific nationalities and open to any member of that linguistic or cultural group. In turn parishes provided spiritual life (the Mass and the Sacraments) and a venue for the celebration of the passages of life from birth to death as well as a faith-based education. Catholic elementary and high schools are the single largest alternative to public schools. Catholic universities and colleges offer alternatives for those who wish a faith-based higher education. Other Catholic institutions have undertaken various works of social provision including the care of abandoned children (orphanages), health care (hospitals and various types of care for the elderly), and assistance to the indigent and homeless. Through these various arms, Catholic life and influence has reached out into every corner of greater Milwaukee, offering services not only to adherents of the Catholic creed but to all who are in need.

Catholic History

A romantic view of Catholic origins in Milwaukee often goes back the visits of Jesuit missionaries, especially the fabled Father Jacques Marquette, who is memorialized for his encampment near the Milwaukee River in 1674.[1] But a more permanent Catholic presence came after Wisconsin became a territory of the United States and especially in the 1830s when urban lands were open for acquisition by land speculators and developers. The small community that became Milwaukee was initially a mission of the Diocese of Detroit that sent Father Patrick O’Kelley to begin a formal Catholic presence. In the traditional Catholic way of claiming territory, he celebrated the Mass in the County Courthouse in 1837. After purchasing lots at Jackson and Martin Streets (today E. State Street), O’Kelley founded what was the first Catholic Church in the city, named St. Luke’s (later renamed St. Peter’s). This small church was the nucleus for subsequent development. O’Kelley was followed in 1842 by Father Martin Kundig, a Swiss-born priest who had formerly worked in Cincinnati and Detroit. Kundig helped encourage the growth of Catholic life in a rapidly growing Milwaukee. Coming just at the time when the city was experiencing a major spurt of growth, he enlarged and renamed St. Luke’s Church. He used booster techniques honed by land speculators, including public events to lobby ecclesiastical officials in America and Rome to make Milwaukee the center of a new ecclesiastical jurisdiction. In 1843 Pope Gregory XVI created the Diocese of Milwaukee, a jurisdiction that at one time encompassed the state of Wisconsin and appointed as its first bishop John Martin Henni, another Swiss-born priest. Making Milwaukee the capital of the Catholic presence in Wisconsin was one of the faith’s first contributions to the rising prestige of the city.[2]

The Daughters of Charity appeared in 1846 and opened St. Rose Orphanage for girls. In addition, they taught at the school that Kundig had established in the basement of St. Peter’s. By the time Milwaukee was chartered as a city in 1846, Catholics in Milwaukee had a respectable presence in the area. Soon a familiar pattern of ethnic differentiation took place as St. Peter’s became a haven for the English-speaking Catholics. German-speaking Catholics, in contrast, broke off from the congregation in 1846 and formed St. Mary’s (on Broadway)—the mother church of other German parishes across the area. Milwaukee’s reputation as a haven for German Catholics was reinforced by the presence of German-speaking bishops, the advent of congregations of sisters who ran schools for the Germans, and the growing number of German priests who came to the area from other parts of the country or who were trained at St. Francis de Sales Seminary (founded in 1845 by Henni in his own residence). Henni created a visible presence for the church in Milwaukee, developing new parishes in each of the initially separate jurisdictions—Holy Trinity Church in Walker’s Point and St. Joseph’s parish in Juneautown. In 1853 he began work on St. John’s Cathedral on Jackson Street. Around the cathedral were Henni’s residence and other institutions of the diocese, and across from the Cathedral was the local courthouse. Catholic buildings were at the heart of the old city. Milwaukee Catholicism continued this pattern of parochial formation down through the twentieth century with the last parish founded within the city limits in 1958 (St. Bernadette). Other Catholic buildings—large convents, schools, hospitals, and other institutions of social provision—began to be erected in virtually every section of the growing city and region.

Catholics as Occupiers of Urban Space

Although encased in demographic identities such as ethnicity or social and economic class, Catholics are people who believe—on a spectrum of intensity—in the creed, the cult, and the code of the Catholic Church. Roman Catholicism is one of major theistic religions of the world. Catholicism is a transnational phenomenon, finding distinct expression in every part of the globe. Milwaukee Catholics share this faith and it often impels them to action. Throughout Milwaukee’s history, Catholics have built magnificent churches, supported schools and social welfare institutions, and worked for local economic and social justice. Any understanding of their urban presence apart from the faith that motivates them is incomplete. Ethnicity and socio-economic class are not surrogates for religious belief.

Catholic institutions in the city of Milwaukee include the cathedral, parish churches, and their attached buildings: convents, rectories (priest residences), and storage facilities. They also include centers for social provision (feeding centers, day care, etc.) as well as schools (elementary, high school, and higher education). Some of these buildings are quite prominent. For example, the motherhouse of the School Sisters of St. Francis spans nearly four city blocks along Layton Blvd. and Greenfield Avenue and features an exquisite chapel. A veritable Catholic city engulfs many acres on the border between the cities of St. Francis and Milwaukee, including the Motherhouse of the Sisters of St. Francis of Assisi, St. Francis de Sales Seminary, the Cousins Center—the administrative central of the diocese—and, behind the seminary, a day care center for adults as well as St. Thomas More High School. The bulk of these buildings are comparatively old. Some of them (e.g., the cathedral, Old St. Mary, Church of the Gesu, and St. Josaphat Basilica) date back to the nineteenth century. Some reflect periodic building expansions in the early 1900s and the 1920s; others were constructed after the Great Depression and World War II. Some Catholic sites no longer exist, victims of freeway construction or urban renewal (St. Joseph’s Church, Blessed Martin DePorres Mission, and Our Lady of Pompeii) or demographic change (St. Leo, St. Anne, St. Thomas Aquinas, St. Gall, St. Boniface—all parishes with large churches and once active memberships and schools).

These institutions reflect millions of dollars in urban investment, and even more in the human resources required to fund and build them. Catholic parishes generally occupied entire city blocks, hosting churches, schools, convents, rectories, and social halls—all on adjacent properties. Their social prominence, their imposing physical presence, and their influence in local neighborhoods contributed to Milwaukee’s economic and social well-being for many years.

Catholics: Ethnicity and Social Networks

Milwaukee developed rapidly as a hub for immigrants. Initially large numbers of German-speaking Catholics came to the city—in part encouraged by the presence of German-speaking bishops (John Martin Henni, Michael Heiss, Frederick Katzer, and Sebastian Messmer) and also German-speaking priests and religious sisters. Germans were initially given a “pride of place” in the arrangement of local church affairs. The first specifically ethnic parish was established for Germans with the foundation of St. Mary’s on Broadway in 1846. Other German parishes developed in every corner of the city. By offering a friendly venue for immigrants with familiar language for confession, sermons, devotions, and church décor, the Catholic Church served as an important contributor to the transition of immigrants to their new urban existence. Irish and English-speaking Catholics also arrived and received a similar indulgence. Already in 1866 there were enough Polish speakers from relevant areas of Europe to create the first Polish parish in the city, St. Stanislaus. A North Side parish, St. Hedwig, attended to Polish spiritual needs in that part of the city. The South Side would become the heartland of Milwaukee’s thriving and vibrant Polonia, and Catholic churches, pastored by Polish priests, became an important part of ethnic accommodation. These parishes were also the sites of internal controversy among Polish Catholics.[3] Similar parishes for Slovaks, Bohemians, Italians, Syrians, Lithuanians, African Americans, Croats, and the Spanish speaking continued this policy. Urban coexistence, to some degree, relied on this presence of the Catholic Church. Newer immigrants, mostly Latinos but also Asians, have also found homes in Catholic sites.

Even viewed apart from the expression of faith, these structures welcomed literally thousands of men, women, and children to their locations every Sunday. Many of the faithful attended parish schools and participated in social activities (dances, civil rights activism, choir singing, youth activities, and athletics). Catholics formed close social networks with each other. Some of this had to do with ethnic identification, but others, particularly in the twentieth century, coalesced around a sharpening sense of Catholic identity defined by strict adherence to the tenets of the Catholic faith, Catholic traditional customs, and the influence of a rather well-defined form of Catholic education. Catholic young people were strongly urged to maintain strict denominational boundaries, to avoid “intermarriage” with Protestants, Jews, and unbelievers, and were encouraged to socialize only with their own through schools as well as devotional and social events. Catholic parishes became marriage brokers. Catholic athletics and social events became occasions for the reinforcement of a distinct Catholic identity. Catholic practices such as Friday abstinence from meat gave birth to the popular Milwaukee fish fry offered by local restaurants. Since the mid-1960s after Vatican Council II, Catholics have often dropped their defensive posture to people of other faiths and to the “outside” world at large. Parish schools have closed, and those that still exist have do not encourage the militant Catholic identity of earlier years.

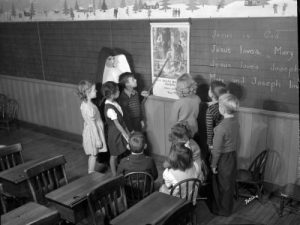

Catholics as Urban Educators

Catholic schools occupy the single largest alternative to public education in Milwaukee to this day. As of 2017, there are twenty-five Catholic elementary schools, nine Catholic high schools, and four Catholic universities and colleges within the metropolitan area of Milwaukee. Religious education for those in public schools constitutes another vast network of Catholic education across greater Milwaukee. In fact, today, the largest numbers of Catholic children are enrolled in these religious education programs, often directed by volunteers.

Milwaukee’s first Catholic school was created in the basement of St. Peter’s Church in 1843. The Daughters of Charity of Emmetsburg, Maryland came to teach the school children. Catholic schools proliferated throughout the nineteenth century—almost always attached to German Catholic parishes and attended by religious sisters, especially the School Sisters of Notre Dame, the School Sisters of St. Francis, and the Sisters of St. Francis of Assisi. English-speaking parishes often relied on the Dominican Sisters of Sinsinawa, Wisconsin. Other religious communities of men and women also came to Milwaukee to staff schools. Many of these sisterhoods had Catholic academies that charged for the attendance of young women. From these academies, which took in a wide age range of girls, free-standing (that is, not linked to a particular parish) Catholic high schools evolved. Parishes also created high school programs, and in the 1920s the archdiocese itself established a free-standing Catholic high school on the city’s North Side, Messmer. Other diocesan high schools that emerged over the years included Pius XI High and Pio Nono High (later St. Thomas More High School). Religious orders like the Society of Jesus, the Society of Mary, the Society of the Divine Savior, the Sisters of the Sorrowful Mother, the Sisters of Charity of the Blessed Virgin Mary, and the Sisters of the Divine Savior all created high schools. The school founded by the Sisters of the Divine Savior still exists as one of the premier sites for the education of Catholic young women. Jesuits from St. Louis established Marquette Academy in 1881 (in the same building as Marquette College). High school boys attending this academy were separated out from the college students and eventually merited a new facility at 34th and Wisconsin.

For its part, Marquette College became the premier Catholic college/university in Milwaukee.[4] Occupying prime space along the city’s main thoroughfare (Grand, later Wisconsin, Avenue) alongside Church of the Gesu, the small Jesuit college became a university in 1907, admitted women, and opened a number of prestigious professional schools, including a respected law school and for a time a medical school. At one point, Marquette was the largest Catholic university in the United States. Its academic, professional, and sports programs are an important part of the city’s intellectual vibrancy. Areas of incidental interaction between Marquette and the city include the university’s considerable financial impact on the downtown, the prominence and elegance of its buildings, and the availability of its faculty to offer comment and insight into urban problems. More formal cooperation with the city in terms of urban stability, deterring urban crime, and working on projects of social harmony and joint economic interest have been an important Catholic contribution to the urban affairs. Thousands of city lawyers, teachers, and religious have received their education at Marquette.

Other Catholic universities include Alverno College, a project of the School Sisters of St. Francis on Milwaukee’s South Side; Cardinal Stritch University, located in Fox Point and sponsored by the Milwaukee-based Sisters of St. Francis of Assisi; and Mount Mary University, established by the School Sisters of Notre Dame. Alverno and Cardinal Stritch both began in their local motherhouses as training facilities for young nuns preparing to go to the elementary and high schools staffed by their orders. Sisters who were sent into classrooms after a short time in formation gradually received their degrees after years of Saturday classes and summer work. Eventually many sisters received advanced degrees at Catholic or other universities and returned to form the faculties of these colleges. Both Alverno and Cardinal Stritch eventually moved out of their motherhouses to free-standing sites where they exist to this day. Both also expanded their programs to include lay persons. Alverno still remains a college for women, whereas Stritch went coeducational in the spring term of 1971. Mount Mary began as a girl’s academy in western Wisconsin and then was transferred to Milwaukee in the 1920s. Notre Dame Sisters attended classes there, but laywomen also were educated at Mount Mary from the start. Each of these colleges has contributed to the economic well-being of Milwaukee, produced graduates who have distinguished themselves in professional careers (law, medicine, education), and also hosted cultural events that have enriched the city’s reputation as a supporter of the fine arts.

Of Catholic schools in recent years, demographic shifts have depleted the enrollments of many Catholic schools all over the city. In the 1970s, Catholic school enrollments took a dramatic plunge. Religious sisters, who in keeping with their vow of poverty generously contributed services, began to withdraw from the schools, resulting in greater financial strains to hire lay faculty—even at non-competitive wages. School closures, like parish closures, were often traumatic to a community—but financial burdens could not be surmounted. The advancing of school choice in 1990 provided public funds for some Catholic schools remaining in Milwaukee, shoring up finances. School consolidations among Catholics in the 2000s have created new “academies” where some school facilities are divided into grades for Catholic schoolchildren who are bussed to new sites. Some school buildings owned by Catholics have been leased by charter schools.

Catholic Leadership in Milwaukee

Many Catholics have served in positions of leadership in city and county governance. Milwaukee has elected only three Catholic mayors: Solomon Juneau, Henry Maier, and Tom Barrett. Other Catholics have served on the Common Council over the years. When the office of county executive was created in the 1960s, its first holders (John Doyne and William O’Donnell) were Catholics, as was their successor, Tom Ament, a graduate of Marquette High School and Marquette University. Several recent Milwaukee chiefs of police have been Catholic (Edward Flynn, Robert Ziarnik, Philip Arreola, and John Polcyn). Although the city went through its bouts of anti-Catholic nativism in the nineteenth century, Catholicism has generally not been an obstacle to the holding of public office. The extent to which religious values have influenced the positions of these Catholic office-holders is not measurable.

The leadership of local Milwaukee archbishops and priests in civic affairs has been significant over the years. John Martin Henni, the first bishop, was a significant contributor to the city’s growth and development. The prestige and prominence of Catholic ecclesiastical leadership was signified for a time with the purchase of the Pabst Mansion in 1908. This was the residence of Milwaukee’s archbishops until it was sold in 1975. Individual priests were quite prominent in the city’s history. Father Wilhelm Grutza planned and helped build the magnificent St. Josaphat Basilica at 6th and Lincoln, the largest Roman Catholic Church in the city. Fellow Polish cleric, Wenceslaus Kruszka, was also a prominent religious and social voice for the city’s Polonia. Father James Groppi, an Italian American priest from Bay View, was the most prominent leader in Milwaukee civil rights campaigns for open housing in the 1960s. Mother Caroline Friess of the School Sisters of Notre Dame helped to build a huge network of sisters and Catholic schools for Milwaukee Catholics. Artists such as Franciscan Sister Thomasita Fessler and School Sister of St. Francis Sister Helen Steffen enhanced the cultural reputation of the city with their paintings and sculptures. Musicians associated with the School Sisters of St. Francis enhanced the area’s musical heritage. And Father Francis Drabinowicz took over the Festival Singers in 1947, renamed them the Bel Canto Chorus, and increased its membership and public reputation as one of several choirs of excellence in the Milwaukee cultural scene.

Catholics through their faith and cultural experience have played a significant role in the shaping of greater Milwaukee. To scan the city’s skyline is to note scores of steeples and domes (some of them admittedly Lutheran—but most of them Catholic). These are brick and mortar incarnations of the presence of a substantial religious community that exists within the dense urban culture of Milwaukee.

Table: Archbishops of Milwaukee

| Served | Archbishop | Lived | Birthplace |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1843-1881 | John Martin Henni (Bishop until 1875) | 1805-1881 | Misanenga, Switzerland |

| 1881-1890 | Michael Heiss | 1818-1890 | Pfahldorf, Bavaria |

| 1890-1903 | Frederick Xavier Katzer | 1844-1903 | Ebensee, Austria |

| 1903-1930 | Sebastian Gebhard Messmer | 1847-1930 | Goldach, Switzerland |

| 1930-1940 | Samuel Alphonsus Stritch | 1887-1958 | Nashville, TN |

| 1940-1953 | Moses Elias Kiley | 1876-1953 | Margaree, Nova Scotia |

| 1953-1958 | Albert Gregory Meyer | 1903-1965 | Milwaukee |

| 1959-1977 | William E. Cousins | 1902-1988 | Chicago, IL |

| 1977-2002 | Rembert G. Weakland | 1927- | Patton, PA |

| 2002-2009 | Timothy M. Dolan | 1950- | St. Louis, MO |

| 2010- | Jerome Edward Listecki | 1949- | Chicago, IL |

Footnotes [+]

- ^ The foregoing history of the Catholic Church in Milwaukee as well as what follows is taken from Steven M. Avella, In the Richness of the Earth: A History of the Archdiocese of Milwaukee, 1843-1958 (Milwaukee: Marquette University Press, 2002) and, by the same author, Confidence and Crisis: A History of the Archdiocese of Milwaukee, 1959-1978 (Milwaukee: Marquette University Press, 2014).

- ^ Peter Leo Johnson, Crosier on the Frontier: A Life of John Martin Henni (Madison, WI: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1958).

- ^ Anthony J. Kuzniewski, Faith and Fatherland: The Polish Church War in Wisconsin, 1896-1918 (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 1981).

- ^ Thomas Jablonsky, Milwaukee’s Jesuit University: Marquette, 1881-1981 (Milwaukee: Marquette University Press, 2007).

For Further Reading

Avella, Steven M. Confidence and Crisis: A History of the Archdiocese of Milwaukee, 1959-1977. Milwaukee: Marquette University Press, 2014.

Avella, Steven M., ed. Milwaukee Catholicism: Essays on Church and Community. Milwaukee: Knights of Columbus, 1991.

Avella, Steven M. In the Richness of the Earth: A History of the Archdiocese of Milwaukee, 1843-1958. Milwaukee: Marquette University Press, 2002.

Johnson, Peter Leo. Centennial Essays for the Milwaukee Archdiocese, 1843-1943. Milwaukee: Husting Printing Company, 1943.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.