The history of alternative medicine in Milwaukee and elsewhere is intrinsically linked to the practice of mainstream medicine. Early medicine in Milwaukee was often a gruesome affair, with bleedings and purges that offered little in the way of relief. The horrors and inadequacies of these treatments bred public distrust in the mainstream medical community. Alternative treatments, while often operating on scientifically-unproven principles, took a more measured and gentle approach that won many local followers.[1]

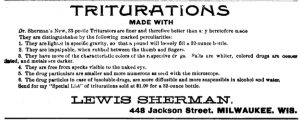

The first major challenge to mainstream medicine in Milwaukee was homeopathy, which came to the city in 1846. First developed by German physician Samuel Hahnemann, homeopathy was based on the idea that a substance which caused symptoms of illness in a healthy person will cure the same symptoms in a sick person. While modern studies suggest that homeopathy offers nothing more than a placebo effect, it found a devoted following in nineteenth-century Milwaukee, particularly among the city’s German population.[2] While homeopaths accounted for just 6 percent of physicians nationwide by the 1870s, they made up nearly a third of Milwaukee’s doctors.[3]

Homeopathy’s wide appeal drew the ire of Milwaukee’s mainstream medical establishment. The Milwaukee City Medical Association forbade its members to engage in professional or social relationships with homeopaths or anyone else practicing alternative medicine (eclecticism, which used botanical remedies instead of drugs, probably had the second largest, yet relatively small, following among seekers of alternative treatments in the city).[4] Nonetheless, homepathics strove for legitimization, opening a medical school and pharmacy in the city and supporting the Milwaukee Academy of Medicine, one of the first societies for medical research in the United States.[5]

While homeopathy prospered in Milwaukee, a national craze for curative mineral baths and spring water brought people from across the country to the many natural springs of Waukesha in the 1890s. Hydropathy promoted the use of waters and baths in lieu of more traditional remedies. Its devotees flocked to Waukesha hydropathy centers, spas, and mud baths in the summer months, temporarily boosting the city’s population by nearly fifty percent. A plan to pipe Waukesha spring water to the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair was thwarted by armed locals, who feared the depletion of their prized waters.[6]

The continued efforts of the homeopaths to achieve legitimacy peaked in the mid-1890s, when, joined by local eclectic physicians, they urged the formation of a state medical licensing board. Wisconsin did not yet require any specific training or licensing for persons practicing medicine.[7] Local homeopaths were especially eager to rid their practice of quacks and frauds.[8] In 1897, the Wisconsin medical licensing board was established. Their approval was required for both mainstream and alternative physicians to practice in the state.[9]

Following the creation of the licensing board, however, alternative practitioners rapidly lost ground to mainstream medicine. Indeed, by the 1920s, the increasingly scientifically-minded homeopath had become so closely aligned with mainstream medicine that it was hard to tell the two groups apart.[10] As the homeopaths blended with the mainstream, the claims of both eclectic and hydropathic medical practitioners in the Milwaukee area were discredited and their treatments fell out of favor.[11]

While some forms of alternative medicine were fading from prominence, others increased their profile during in the early twentieth century. Osteopaths claimed to be able to cure illness via physical manipulation of the muscles and bones. Chiropractors claimed to do the same through manipulation of the spinal column. Osteopaths first appeared in 1897; Cherry’s Milwaukee Institute, one of only twelve osteopathic schools in the nation, opened the following year.[12] Chiropractors followed a decade later, but were less popular in Milwaukee than in more rural areas of the state.[13] Each of these practices was particularly appealing to women, as they did not require patients to disrobe for evaluation or treatment.[14]

Milwaukee shared in the national decline in the practice of alternative treatments between the 1920s and the 1970s, which saw the introduction of antibiotics and other advances in medical science; chiropractic was the only form of unconventional medicine to maintain a presence in the Milwaukee area.[15] Local chiropractors adjusted to the new climate by narrowing their claims, insisting that their methods were effective only on spinal and joint maladies, not disease, and that they were a complement to, not a substitute for, mainstream medicine. Still, the distrust of the mainstream medical community toward alternative medicine remained intact and attacks on chiropractic practices in Milwaukee continued through the 1970s.[16]

At the same time, although more traditional doctors and their patients remained wary, increasing numbers of Milwaukeeans were turning to new forms of alternative medicine, including many labeled “Eastern medicine.” Local physicians trained in acupuncture began offering the treatment in the Milwaukee area in 1972, the same year President Nixon made his landmark visit to China.[17] Reflecting on acupuncture in 1980, the Milwaukee Sentinel reported that Nixon’s visit made Eastern medicine “fashionable” and such treatments had been increasing in popularity in the years since.[18]

Massage therapy and herbal medicine, both adapted forms of Eastern medicine, followed acupuncture into Milwaukee and increased in popularity through the late 1980s. Like Milwaukee’s chiropractors and acupuncturists, practitioners of massage therapy and herbal medicine promoted them as complementary treatments—to be used in conjunction with more traditional health care.[19]

By the 1990s, alternative medicine had gained a level of acceptance never before seen in Milwaukee. In 1995, a Milwaukee Journal Sentinel article reported that since 1985, the number of massage businesses listed in the phone book had increased from 21 to 90, with most offering forms of therapeutic massage.[20] Reporting less than a decade later, the paper wrote that many area hospitals—Aurora, Covenant, and Columbia St. Mary’s among them—offered various forms of alternative medical treatment and that more insurers were covering alternative treatments. Furthermore, many local medical professionals had embraced the idea of alternative medicine as a complementary treatment.[21]

Footnotes [+]

- ^ Elizabeth Barnaby Keeney, Susan Eyrich Lederer, and Edmond P. Minihan, “Sectarians and Scientists: Alternatives to Orthodox Medicine,” in Wisconsin Medicine: Historical Perspectives, ed. Ronald L. Numbers and Judith Walzer Leavitt (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1981), 47.

- ^ Kenney, Lederer, and Minihan, “Sectarians and Scientists,” 48.

- ^ Kenney, Lederer, and Minihan, “Sectarians and Scientists,” 49.

- ^ Kenney, Lederer, and Minihan, “Sectarians and Scientists,” 48, 53.

- ^ Kenney, Lederer, and Minihan, “Sectarians and Scientists,” 48, 51.

- ^ Kathleen Poplawski, “Hope Springs Eternal, and Other Famous Spas,” Milwaukee Journal, February 18, 1974, p. 14.

- ^ Kenney, Lederer, and Minihan, “Sectarians and Scientists,” 58.

- ^ Kenney, Lederer, and Minihan, “Sectarians and Scientists,” 56.

- ^ Kenney, Lederer, and Minihan, “Sectarians and Scientists,” 58.

- ^ Kenney, Lederer, and Minihan, “Sectarians and Scientists,” 58.

- ^ Kenney, Lederer, and Minihan, “Sectarians and Scientists”; “Hope Springs Eternal.”

- ^ Kenney, Lederer, and Minihan, “Sectarians and Scientists,” 62.

- ^ Kenney, Lederer, and Minihan, “Sectarians and Scientists,” 66, 67.

- ^ Kenney, Lederer, and Minihan, “Sectarians and Scientists,” 59.

- ^ James Whorton, “Countercultural Healing: A Brief History of Alternative Medicine in America,” PBS Frontline website, posted November 4, 2003, accessed April 5, 2015.

- ^ “New Fight Seen by Chiropractor,” Milwaukee Sentinel, October 24, 1972, 5.

- ^ Dorothy Austin, “Acupuncture’s Twirling Needles Ease Pain of Facial Tic,” Milwaukee Sentinel, December 15, 1972, 1.

- ^ Michael Chancellor, “Medical Student Learns Acupuncture in China,” Milwaukee Sentinel Good Morning, November 19, 1980, 1.

- ^ Jerry Resler, “Herbal Renewal,” Milwaukee Sentinel, July 20, 1993, 1C; John Fauber, “Hands-On Debate,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, April 17, 1995, 4G-5G.

- ^ John Fauber, “Hands-On Debate,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, April 17, 1995, 4G-5G.

- ^ Susanne Quick, “Delving into Alternative Care,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, October 18, 2004, G1.

For Further Reading

Numbers, Ronald, and Judith Walzer Leavitt, eds. Wisconsin Medicine: Historical Perspectives, Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1981.

Whorton, James C. Nature Cures: The History of Alternative Medicine in America. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.