Brewing beer has been a central industry in Milwaukee since the mid-nineteenth century and frames the city’s identity—more than any other single industry. According to Thomas Cochran, one of the industry’s major historians, “Milwaukee’s beer became famous throughout the world within the course of the first three decades of its manufacture.”[1] The city and the industry grew up together and have prospered and weathered several phases of boom and bust, changes in taste, and in the political regulation, taxation and prohibition of alcoholic beverages.

Pioneer Brewing in Milwaukee

Milwaukee’s brewing industry formed in the early 1840s, and developed rapidly along with the burgeoning frontier settlement. European immigrants brought both a local market for traditional beer styles of their homelands and the skilled brewers able to produce such beverages. Although German brewers are most known for their role in shaping the industry from its earliest origins, it was a group of Welsh immigrants—Richard G. Owens, William Pawlett, and John Davis—who established the city’s first brewery in 1840 near the North Pier (Lake Michigan) on Huron Street (now E. Clybourn), known as the Milwaukee Brewery and later the Lake Brewery.[2] Herman Reutelschöfer established Milwaukee’s first German brewery on the northwest corner of Hanover and Virginia shortly thereafter.[3]

Brewing proved to be a dynamic and volatile business in early Milwaukee as approximately thirty-five breweries were established between 1840 and 1860.[4] These were primarily small artisanal shops, formed through family connections or brief partnerships that served customers in the immediate vicinity or through a connected or affiliated saloon, beer hall, or restaurant—much like modern brewpubs.[5] Most of these early breweries were located just east and west of the Milwaukee River, north of downtown. The Milwaukee River provided water essential to the brewing process, and the ice necessary for maintaining the proper temperature for the conditioning of German lager in storage cellars that brewers dug into the bluffs along the river. Milwaukee’s early breweries were small, one- to two-story, wood-frame structures, which housed the entire brewing process—from malting to conditioning—and the residence of the brewer and his family.[6]

Initially, brewing equipment and materials were difficult to come by in frontier Milwaukee. The pioneer brewers improvised. The first batches of Owens’ Milwaukee Brewery were produced in a five-barrel brew kettle composed of a wooden box lined with copper, with barley shipped in from Michigan City, Indiana.[7] The Best Brewery—predecessor to the Pabst Brewing Company—acquired their first brew kettle in 1844, by appealing to a local iron maker to construct one with iron brought in from Racine and Kenosha, on the promise of future payment and free beer for life.[8] Difficulties in securing equipment, materials, and starting capital—especially during the financial panic of 1857, and the Civil War—and the growing competition in the area strained the solvency of Milwaukee’s early breweries, and most closed within a few years after starting.[9]

Milwaukee’s early breweries produced a wide range of beers familiar to local tastes. Both the Owens Brewery and the Blossom brothers’ Eagle Brewery (Northwest corner of 8th and Prairie, now 8th and W. Highland Ave.) brewed British and American-style ales and porters. The Gipfel Union Brewery (417 Chestnut, now W. Juneau Ave.) brewed alt and weiss ales. Herman Reutelschöfer introduced German lagers to Milwaukee, which become the primary staple of the city’s increasingly German-dominated brewing industry by the 1860s.[10]

Industrialization

Several major beer manufacturers emerged in the city in the 1850s. Pabst (as Best), Schlitz, Blatz, Miller, and Gettelman are among the most recognizable of these early industrial firms, but brewers like Jacob Obermann, Franz Falk, Jung & Borchert, and the Cream City Brewery also jockeyed to become Milwaukee brewing giants.

Many of Milwaukee’s emergent industrial brewers had existing knowledge and experience in industrial brewing in Germany, and came to the United States to establish ventures in an open and developing market. Jacob Best, Sr. owned a brewery and winery in Mettenheim, Rheinhessen, and moved his operations to Milwaukee after his sons reported the potential for growth.[11] Miltenberg, Bavaria, especially, produced a significant number of Milwaukee’s brewing giants. Valentin Blatz trained in his father’s brewery (the Hop Garden Brewery) in Miltenberg and other large breweries in the area before coming to the United States.[12] August Krug and his father Georg sold the Lion Brewery (now the Faust Brewery) in Miltenberg, and fled to the United States as political refugees after the 1848 revolution, establishing a guesthouse and brewery in Milwaukee that grew in the hands of August’s descendants (the Uihleins) as the Schlitz Brewing Company. Franz Falk had trained as a brewer at the Krugs’ Lion Brewery in Miltenberg before moving in 1848 to Milwaukee, where he worked as a foreman for the Krugs again until he opened his own brewery in 1856.[13]

Other German immigrants also entered the upper levels of the city’s industry. Frederick Pabst, Emil Schandein, and Joseph Schlitz helped transform the Best and Krug breweries, respectively, into giant national enterprises. These newcomers entered the industry through marriage, and the city’s brewing industry remained in the hands of family dynasties, like the Pabsts, Uihleins, Blatzs, Millers, and Gettelmans, into the late twentieth century.[14]

Milwaukee delivered a promising business environment. The city’s rapid growth and large German community supplied an expanding base of local beer consumers. Saloons, beer gardens, and beer halls appeared in neighborhoods throughout the city, and served as the primary local retail outlets.[15] Civic leadership and philanthropy also proved significant to local marketing, as beer sales increased with the brewers’ local prestige.[16] Milwaukee’s major brewers invested considerably in city governance as early as the 1850s, serving as aldermen, assessors, militia officers, and in other civic posts. Charles Melms, Valentin Blatz, and Frederick Pabst were admitted to the Yankee-dominated Chamber of Commerce in the 1860s—a testament to their growing prominence in the overall community.[17]

Technological developments in brewing and new railroad connections in the region allowed Milwaukee’s largest brewers to seek bigger markets for their products, beginning in the 1850s and 1860s.[18] Rapidly growing Chicago—with its large beer-drinking immigrant population, only ninety miles to the south—became the most significant consumer of Milwaukee beer. While Chicago had developed its own brewing industry, a beer shortage in 1854 and the completion of the Chicago and North Western Railway’s Milwaukee-Chicago connection in 1855 helped initiate Chicago’s dependence on Milwaukee beer.[19] Milwaukee’s largest brewers opened agencies in Chicago to facilitate their trade—Best in 1857, Blatz in 1865, and Schlitz in 1868.[20] The Great Chicago Fire of 1871 further galvanized this dependence. As most of the city’s breweries were destroyed, Milwaukee brewers took the opportunity to claim the market. Overall sales of Milwaukee brewers increased by 44 percent between 1871 and 1872. Schlitz alone recorded over a 100 percent increase that gave credence to their later claim to have been “the beer that made Milwaukee famous.”[21]

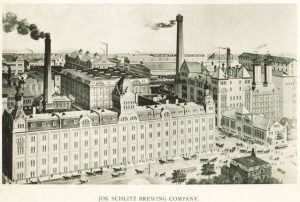

Increased demand prompted brewers to expand their plants and introduce the latest in scientific and mechanized brewing technologies. A key feature of these new industrial breweries was the separation of the brewing process into different buildings for malting, brewing, fermenting, storage, and packaging. The small, one-building operations of the 1840s gradually grew into large, multi-block complexes by the 1880s.[22] The Best Brewing Company also expanded their operations by purchasing their rival, the Melms Brewery (on the corner of Oregon and Hanover, on the southern banks of the Menomonee River), in 1869. This new South Side Brewery, combined with their original Empire Brewery, gave Best a leading edge over other local rivals and sparked mergers and industry consolidation in Milwaukee.[23]

Support industries also emerged, including malting houses, cooperages, glass blowers, bottlers, and liveries.[24] The harvesting and storage of ice from local rivers and lakes during the area’s long winters gave Milwaukee’s brewers a distinct advantage over their regional competitors until the gradual introduction of practical artificial refrigeration between the 1870s and 1890s.[25]

Many brewers continued to live near their plants into the later decades of the nineteenth century.[26] Moreover, most of the growing number of brewery workers resided in the expanding working-class neighborhoods surrounding the plants. The mobility and living conditions of skilled brewery labor improved as they became more firmly organized and negotiated union contracts in the later decades of the nineteenth century.[27]

Industrial brewing was not without its obstacles. Major fires destroyed significant portions of the Blatz brewery in 1872, the Gettelman brewery in 1877, and the Pabst brewery in 1879. All had the capital and insurance to take the opportunity to rebuild with expanded and more modernized facilities.[28]

Increased federal regulation prompted German-American brewers already quite familiar with such regulation prevalent in the German-speaking states of Europe to organize their interests. The Revenue Act of 1862 placed a $1.00 tax on every barrel of beer sold, and required a $100 license for brewers producing over 500 barrels annually.[29] Although the act targeted distilled spirits more than beer, it also exposed the industry’s vulnerabilities to more expanded taxation. Brewers from around the nation organized the United States Brewers’ Association (USBA) to lobby for their interests in Washington. Charles Melms was appointed to the committee to draft protective legislation, and Milwaukee brewers were active from the second meeting on. The USBA studied European taxation systems, recommended a stamp system (which Congress enacted in 1866),[30] and organized resistance to early attempts at enacting Prohibition.[31]

Milwaukee Beer, National Beer

In the 1870s, Milwaukee’s major industrial brewers set their sights beyond local and regional markets to national and international markets. Consumers’ growing taste for lager throughout the United States and continued improvements in production techniques facilitated the expansion of Milwaukee into one of the largest brewing centers in the United States.[32] Chicago remained a significant market. Around 20 percent of Pabst’s production alone went to Chicago, and Pabst, Schlitz, and Blatz accounted for 32.3 percent of all beer sold in Chicago in the 1880s.[33]

Milwaukee brewers adopted “scientific brewing”—the refinement of the craft of brewing into a systematic industrial process, including innovations in production, packaging, and transportation that allowed them to transport beer over longer distances to new markets and deliver a standardized national product.[34] Milwaukee’s breweries were among the first national breweries to introduce mechanized production systems, bottling machinery, and artificial refrigeration, as well as apply the latest in pasteurization techniques and chemistry.[35]

Milwaukee’s major brewers opened agencies in cities throughout the United States that coordinated Milwaukee beer shipments with local retailers and consumers. They adopted and embellished the old British and German “tied-house” system, where brewers built and maintained saloons that they rented out to aspiring saloonkeepers in exchange for the exclusive service of their product.[36] Pabst, Schlitz, Blatz, and Miller jockeyed for prime saloon locations in working-class neighborhoods—primarily in Milwaukee and Chicago—often competing for “regular” drinkers right across the street from one another. By 1887, Schlitz already owned around fifty such retailers in Milwaukee alone.[37]

Milwaukee’s brewers also placed their mark on the built environment and leisure spaces. They acquired and built beer gardens, beer halls, and, later, amusement parks in various parts of Milwaukee, including notable downtown destinations, like the Schlitz Palm Garden and the Pabst Gargoyle Restaurant. They acquired and built large hotels, theaters, and restaurants, primarily in downtown Milwaukee, but also in New York, Chicago, San Francisco, Minneapolis, and other cities.[38]

National competitions provided significant opportunities for Milwaukee breweries to secure product recognition. Local beer fairs began in Milwaukee in the 1870s. Beer competitions at the late nineteenth century world’s fairs gave the emerging brewing giants an opportunity to compete and promote on a national and international stage. Blatz and Pabst both won gold medals at the 1876 Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia, and Pabst won gold at the 1878 Paris World’s Fair and first prize at the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago.[39]

Milwaukee brewers also committed an increasing amount of their operating budget on advertising—especially as more beer drinkers turned to buying bottled beer for consumption at home. Some of Milwaukee’s most iconic brewing imagery, like Pabst’s blue ribbon, Miller’s “girl in the moon,” Schlitz’s globe, and Blatz’s triangle, emerged in the pages of periodicals, pamphlets, signs, postcards, souvenirs, and promotional novelties at this time.[40]

The city’s brewing industry also consolidated, shrinking to only nine firms by 1885.[41] In 1888, two of Milwaukee’s industrial brewers, the Franz Falk Brewing Company and the Jung and Borchert Brewing Company, executed one of the largest brewing mergers to date, forming the Falk, Jung, and Borchert Brewing Company.[42] Pabst bought the merged company out in 1892. British investors bought Blatz for $3,750,000 in 1891.[43]

Prohibition

National Prohibition, enacted first as a wartime measure and quickly codified as a 18th Amendment to the Constitution in 1919, dealt a devastating blow to Milwaukee’s brewing industry but did not kill it. The movement for Prohibition had assailed brewers’ saloon ownership and directly linked the brewing industry to intemperance, prostitution, and other social problems. Prohibitionists also accused the German-dominated industry of supporting a foreign enemy during the First World War.[44]

Despite Prohibition, the major brewing companies, including Pabst, Schlitz, Blatz, and Miller—along with a few mid-level breweries (Gettelman, Cream City, and Independent)—restructured their operations and survived. They produced and packaged other products, including soda, tonic water, chocolate, malt syrup, milk, cheese, and the “near beer” (1/2 of a percent alcohol) that the Volstead Act deemed acceptable.[45] Milwaukee’s larger brewers liquidated real estate and other assets and rented out unused facilities to other businesses.[46]

Prohibition also severely impacted brewery workers, as major brewers cut their workforce in half, attempted to force major wage reductions, and tried to break the union’s “closed shop” agreement. Brewery workers went on strike in 1922. While Pabst and Gettelman held out from signing a union contract until 1926, the strike proved successful and initiated an era of labor peace in the industry until the 1950s.[47]

Post-Prohibition, Post-War Boom, and Consolidation

The repeal of national Prohibition in 1933 revived Milwaukee’s historic industry with new vigor. All of Milwaukee’s brewing giants reopened, and some new, smaller firms were established, including the Banner Brewing Co., Fischbach Brewing Co., Capitol Brewing Co., and the Century Brewing Co.—though most of these had closed by the 1940s.[48]

One provision of repeal, however, was that brewers could no longer own or subsidize exclusive retail outlets.[49] Yet, post-Prohibition independent taverns remained important outlets for Milwaukee beer, and brewers were still able to provide taverns with beer signs—many of which continue to adorn the exteriors and windows of corner taverns in neighborhoods throughout Milwaukee to this day.[50]

In the 1930s, as beer drinkers increasingly bought packaged beer for consumption at home, Milwaukee brewers began shifting the focus of their production and packaging to home sales, adopting new innovations in bottling and long-term preservation, as well as promising new canning technology. Tavern owners also turned to packaged beer, finding it simpler than maintaining a draught system of many kinds of beer.[51]

Advances in radio, television, and other mass media brought greater importance to creative advertising to compete for home beer consumers, and Milwaukee brewers took advantage of the new media as program sponsors and advertisers.[52]

Pre-Prohibition trends of national consolidation and expansion in the industry continued with more vigor after repeal. National beer sales reached their pre-Prohibition levels in 1940 with only half as many breweries in operation.[53] Milwaukee stood out as the center of the American brewing industry. By 1949, Wisconsin caught up with New York as the nation’s leading beer producing states, with Milwaukee as Wisconsin’s dominant brewing city.[54] By the mid-1970s, Milwaukee’s remaining big three—Pabst, Schlitz, and Miller—were among only five breweries producing over 10 million barrels a year nationally.[55] Schlitz especially prevailed during this time, battling with Anheuser-Busch for leadership of the national market.[56]

Accompanying this boom was the gradual ascendancy of a singular, “American” lager out of the many different styles that Milwaukee brewers produced. Milwaukee brewers sent beer overseas during the Second World War. Returning GIs demanded the brands they grew attached to after the war. Miller especially positioned themselves well for such production, having scaled back to one brand: Miller High Life.[57]

From the 1930s to the 1950s, Milwaukee’s brewing giants also began establishing satellite plants in cities throughout the United States.[58] In 1932 Pabst merged with the Peoria-based Premier Malt Products Company, turning the plant over to Pabst production.[59] Pabst purchased the Hoffman Beverage Company of Newark, New Jersey in 1945, and the Los Angeles Brewing Company in 1948.[60] Schlitz purchased the Ehert brewery in Brooklyn in 1949, and built a massive new brewery in Van Nuys, California in 1954.[61] Milwaukee remained as corporate headquarters.

Corporate consolidation also continued. Blatz and Gettelman did not modernize their operations fast enough to remain competitive in the national market and became the first of the city’s giants to fall to national industry restructuring. Blatz sold out to Pabst in 1958 and closed its plant in 1959.[62] Gettelman sold out to their next-door neighbor Miller in 1961, which merged the two plants in 1971.[63] Gettelman’s “Milwaukee’s Best” and Blatz brands lived on, though, brewed by their new owners.

Global Brewing and Microbrewing

Milwaukee’s brewing giants continued their domination of the national industry through the 1970s. As local and national markets became saturated, however, industry leaders turned more to buying out competing labels, diversifying interests, building greater media exposure, improving packaging, and slimming down production costs. The industry became increasingly globalized by the 1980s and 1990s, and import beers gained an increasing share of the American market. Brewing in Milwaukee underwent yet another period of restructuring.

Perhaps most indicative of the turbulence in Milwaukee during this period are Miller’s rise and Schlitz’s meteoric fall. Miller came late to expansion, but, as a result, was able to take advantage of growing industry consolidation, purchasing Gettelman in 1961, and other breweries in Texas and California in 1966. This growth accelerated after the Philip Morris Corporation purchased Miller in 1969. The new parent company introduced new marketing and development programs that drastically improved Miller’s market standing and built new plants in New York, North Carolina, California, Georgia, and Ohio in the 1970s.[64] Miller also achieved more security by introducing Miller Lite, gaining the distribution rights to Löwenbrau in the 1970s, developing Miller Genuine Draft, and acquiring Leinenkugel’s in the 1980s.[65]

Schlitz, by contrast, was irreparably marred by a series of missteps. The most damaging was the 1967 introduction of “accelerated batch fermentation”—a new brewing process that allowed the brewery to produce beer more cheaply. Consumers found the brand of lower quality. Sales plummeted and the company moved to correct the problems too late to recoup its former position in the industry.[66] In 1981, Schlitz attempted to reduce production costs by forcing concessions on its workers, who went out on strike. Schlitz closed the Milwaukee plant and sold out to the Stroh Brewing Company in 1982.[67]

Sold to venture capitalist Paul Kalmanovitz’s S&P Company in 1985, Pabst also faltered and closed its Milwaukee operations in 1996.[68] The corporation survived as a holding company and “virtual brewer,” contracting out the brewing of its growing stock of familiar brands, like Schlitz and Blatz, to other large firms, including Miller.[69]

Miller remained the last of Milwaukee’s brewing giants. In 2002, Miller was purchased by South African Breweries, forming SABMiller, and bringing the brewing of global brands, like Pilsner Urquell and Peroni to Milwaukee.[70] Similarly, a joint venture with Molson Coors formed as MillerCoors in 2007 brought the brewing of Coors, Molson, and Blue Moon to Milwaukee, as well.[71]

Though most of the old giants have gone, brewing remains a dynamic industry in Milwaukee. Prohibition-era restrictions on beer production, distribution, and homebrewing were relaxed in the 1970s. New small, craft brewers emerged in Milwaukee that developed and perfected a wide variety of beer styles. Sprecher (1985) and Lakefront (1987) especially benefitted from the city’s industry-old craft tradition, and the reemerging local taste for a broader array of styles and higher-quality beer.[72] Many other microbreweries and brewpubs have followed. Lakefront has grown into a regional craft brewery.[73] Brewing remains a vibrant part of the city’s economy, and Thomas Cochran’s claim that brewing was central to the city’s identity still rings true.[74]

Footnotes [+]

- ^ Thomas C. Cochran, The Pabst Brewing Company: The History of an American Business (New York: New York University Press, 1948), 42.

- ^ This brewery was also commonly known as the Owens Brewery. Owens and his associates sold the brewery in 1864 to M. W. Powell and Company, who abandoned it in 1880 as lager became most popular in the city. Bayrd Still, Milwaukee: The History of a City (Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1948), 64; One Hundred Years of Brewing (Chicago and New York: H.S. Rich & Co, 1903; repr., New York: Arno Press, 1974), 212; Jerry Apps, Breweries of Wisconsin (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1992), 16; Wayne L. Kroll, Badger Breweries: Past and Present (Jefferson, WI: Wayne L. Kroll, 1976) 78, 83; John Gurda, Miller Time: A History of the Miller Brewing Company, 1855-2005 (Milwaukee: Miller Brewing Company, 2005), 18.

- ^ Apps refers to Reutelschöfer as Reuthlisberger, and Stanley Baron cites other spellings as Reidelschoefer, Reutelschoefer, and Reidelschofer. However, both Susan K. Appel and Bayrd Still use Reutelschöfer. Apps, Breweries of Wisconsin, 16; Stanley Baron, Brewed in America: The History of Beer and Ale in the United States (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1962), 185; Susan K. Appel, “Building Milwaukee’s Breweries: Pre-Prohibition Brewery Architecture in the Cream City,” Wisconsin Magazine of History 78 (3) (Spring 1995): 164; Still, Milwaukee, 64; Gurda, Miller Time, 18.

- ^ Kroll, Badger Breweries; Gurda notes that there were as many as twenty-six breweries operating in 1856 alone, Gurda, Miller Time, 18; Brenda Magee claims that there were over forty breweries operating in Milwaukee by 1860, Brenda Magee, Brewing in Milwaukee (Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2014), 13.

- ^ Kathleen Neils Conzen, Immigrant Milwaukee: Accommodation and Community in a Frontier City (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1976), 104-105.

- ^ Appel, “Building Milwaukee’s Breweries,”164-166; Cochran, Pabst, 19.

- ^ Apps, Breweries of Wisconsin, 16.

- ^ Cochran, Pabst, 20-21. Cochran’s source claims this to be the first “steam boiler” ever produced in Wisconsin.

- ^ Conzen, Immigrant Milwaukee, 104; Kroll, Badger Breweries; Cochran, Pabst, 43-46.

- ^ Conzen, Immigrant Milwaukee, 103; Baron, Brewed in America, 185; Gurda, Miller Time, 18-21; Kroll, Badger Breweries; According to Appel, different late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century articles in The Western Brewer cited either Pabst or Blatz as Milwaukee’s first lager brewery. While Reutelschöfer was more likely the first, according to Baron, Pabst and Blatz were certainly among the earliest. Appel, “Building Milwaukee’s Breweries,” 164.

- ^ Cochran, Pabst, 3-10.

- ^ One Hundred Years of Brewing, 333.

- ^ Wilhelm Otto Keller, “From Miltenberg to Milwaukee: Beer Magnates from the Lower Main Area in the United States in the Nineteenth Century,” trans. Michael R. Reilly, Sussex-Lisbon Area Historical Society, Inc., last modified March 28, 2013, accessed January 16, 2014, http://www.slahs.org/brewery/miltenberg.htm.

- ^ Baron, Brewed in America, 288.

- ^ Cochran, Pabst, 31-32, 41; Gurda, Miller Time, 20-22.

- ^ Cochran, Pabst, 67-68.

- ^ For example, Jacob Best, Sr. was elected Second Ward assessor in 1850; Philip Best was appointed lieutenant of the Milwaukee Dragoons in 1851; Jacob Best, Jr. was elected Second Ward alderman in 1861; Frederick Pabst was elected Second Ward aldermen in 1863; Valentin Blatz was elected alderman in 1872; Charles Melms was elected to the Chamber of Commerce in 1861; Pabst and Blatz were elected to the Chamber of Commerce in 1865; and Pabst served as City Water Commissioner from 1871-1877; Cochran, Pabst, 35-36, 48, 68; The United States Biographical Dictionary and Portrait Gallery of Eminent and Self-Made Men, Wisconsin Volume (Chicago: American Biographical Publishing Company, 1877), 670-673.

- ^ Baron, Brewed in America, 257.

- ^ Cochran, Pabst, 31; Gurda, Miller Time, 26.

- ^ Perry R. Duis, The Saloon: Public Drinking in Chicago and Boston, 1880-1920 (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1983), 18-19.

- ^ Duis, Saloon, 19; Cochran, Pabst, 55-56.

- ^ Cochran, Pabst, 58-59, 86-91.

- ^ Cochran, Pabst, 59-61.

- ^ Cochran, Pabst, 74-78.

- ^ Cochran, Pabst, 77-78, 97-98, 107-110; Baron, Brewed in America, 235-237.

- ^ Cochran, Pabst, 59-61.

- ^ Cochran, Pabst, 253-255.

- ^ Cochran, Pabst, 87.

- ^ Cochran, Pabst, 50.

- ^ Cochran, Pabst, 51-53.

- ^ Cochran, Pabst, 53; Gurda, Miller Time, 33.

- ^ Cochran, Pabst, 55; Gurda, Miller Time, 34.

- ^ Duis, Saloon, 19.

- ^ Cochran, Pabst, 102.

- ^ Cochran, Pabst, 102-128; Gurda, Miller Time, 61-64.

- ^ Baron, Brewed in America, 272-273.

- ^ Baron, Brewed in America, 272; Gurda, Miller Time, 40-41, 70-76.

- ^ Baron, Brewed in America, 272; Cochran, Pabst, 210-213.

- ^ Industrial History of Milwaukee, the Commercial, Manufacturing, and Railway Metropolis of the Northwest (Milwaukee: E. E. Barton, 1886), 103–104; Cochran, Pabst, 64, 423-425.

- ^ Cochran, Pabst, 213-222; Gurda, Miller Time, 79-85; Dave Herrewig, “The Miller High Life Girl in the Moon,” [now titled “Here’s What We Know about the Miller High Life Lady”] MillerCoors, Behind the Beer, November 6, 2013.

- ^ Cochran, Pabst, 66-67; Gurda, Miller Time, 34-35.

- ^ Baron, Brewed in America, 268.

- ^ Cochran, Pabst, 424; One Hundred Years of Brewing, 333; “Chicago and Milwaukee Beer Trust,” Chicago Daily Tribune, February 17, 1891, 1; Amy Mittelman, Brewing Battles: A History of American Beer (New York: Algora, 2008), 65, 121.

- ^ Baron, Brewed in America, 290-291; Cochran, Pabst, 302-308; Gurda, Miller Time, 92-98.

- ^ Cochran, Pabst, 333-337; Gurda, Miller Time, 99-100.

- ^ Cochran, Pabst, 326; Gurda, Miller Time, 100-102.

- ^ Cochran, Pabst, 337-340.

- ^ Kroll, Badger Breweries.

- ^ Cochran, Pabst, 367-368; Gurda, Miller Time, 112.

- ^ Cochran, Pabst, 368; Gurda, Miller Time, 112-113.

- ^ Baron, Brewed in America, 326-327.

- ^ DwightFrye, “Blatz Beer,” Dailymotion video, 1:00, published December 20, 2006, accessed April 29, 2014; Carl H. Miller, “Beer and Television: Perfectly Tuned In,” BeerHistory.com, accessed March 9, 2014.

- ^ Baron, Brewed in America, 331.

- ^ William Owen Baldwin, “Historical Geography of the Brewing Industry: Focus on Wisconsin,” (Ph.D. diss, University of Illinois, 1966), 104, 106, 110.

- ^ The other two were Anheuser-Busch and Coors. Charles F. Keithahn, The Brewing Industry: Staff Report of the Bureau of Economics, Federal Trade Commission (Washington, D.C.: Federal Trade Commission, 1978), 24, 185; Victor J. Tremblay and Carol Horton Tremblay, The U.S. Brewing Industry: Data and Economic Analysis (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2005), 67-101.

- ^ Apps, Breweries of Wisconsin, 104-105.

- ^ Gurda, Miller Time, 117-118; Apps, Breweries of Wisconsin, 41-42, 116-117.

- ^ Baron, Brewed in America, 340.

- ^ Cochran, Pabst, 355-365.

- ^ Cochran, Pabst, 373-374; Baron, Brewed in America, 341

- ^ Baron, Brewed in America, 340-341.

- ^ Pabst was forced to sell Blatz to G. Heilemann in a federal anti-trust suit in 1969; Apps, Breweries of Wisconsin, 101.

- ^ Apps, Breweries of Wisconsin, 207; Nancy Moore Gettelman, A History of the A. Gettelman Brewing Company: One Hundred and Seven Years of a Family Brewery in Milwaukee (Milwaukee: Procrustes Press, 1995), 141-147; Gurda, Miller Time, 141.

- ^ Gurda, Miller Time, 153-156.

- ^ Gurda, Miller Time, 150-152, 161-163; Philip Van Munching, Beer Blast: The Inside Story of the Brewing Industry’s Bizarre Battles for Your Money (New York: Times Business, 1997), 33-35; Apps, Breweries of Wisconsin, 117-121.

- ^ Apps, Breweries of Wisconsin, 108-109; Van Munching, Beer Blast, 41-49; Jacques Neher, “What Went Wrong?: Part II,” Milwaukee Journal, June 9, 1981, part 2, p. 9.

- ^ Lawrence C. Lohmann, “Schlitz Strike Raises Fears About Future Here,” Milwaukee Journal, June 1, 1981, part 1, p. 1; Apps, Breweries of Wisconsin, 109-111.

- ^ Tina Daniell, “It’s Official: Kalmanovitz Has Pabst,” Milwaukee Journal, February 26, 1985, part 3, p. 4; Apps, Breweries of Wisconsin, 131; Tremblay and Tremblay, U.S. Brewing Industry, 83; Georgia Pabst, “Pabst Shutdown Decision ‘Deplorable,’ Kleczka Says,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, October 18, 1996, p. 4A; Alan J. Borsuk, “Brewer Has Gone from Rock Solid to Ground Down,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, October 18, 1996, p. 1A, 12A; James E. Causey and Rick Romell, “Taps For Pabst,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, October 18, 1996, p. 1A, 12A.

- ^ Mittelman, Brewing Battles, 167; Gurda, Miller Time, 167-168; Tom Daykin, “Pabst Closing Its Last Brewery,” JSOnline, published July 24, 2001, accessed May 12, 2014, http://www3.jsonline.com/bym/news/jul01/pabst24072301a.asp?referral=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.jsonline.com%2Fbym%2Fnews%2Fjul01%2Fpabst24072301a.asp; Pabst Brewing Company website, Beers, accessed March 30, 2014.

- ^ Mittelman, Brewing Battles, 199; Gurda, Miller Time, 170-171.

- ^ Tom Daykin, “Ganging Up on Bud,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, October 10, 2007, 1A, 8A.

- ^ Lakefront Brewery, “Our History,” accessed May 7, 2015, Thomas C. Cochran, The Pabst Brewing Company: The History of an American Business (New York: New York University Press, 1948), 46-50, 102-103.; Sprecher Brewing Company, “Brewery History,” Sprecher Brewery website, accessed May 7, 2014.

- ^ Tom Daykin, “Toasting a Milestone: Lakefront Brewery Reaches ‘Craft Brewery’ Status,” JSOnline, published November 23, 2010, accessed May 7, 2014.

- ^ Cochran, Pabst, 42.

For Further Reading

Appel, Susan K. “Building Milwaukee’s Breweries: Pre-Prohibition Brewery Architecture in the Cream City.” Wisconsin Magazine of History 78 (3) (Spring 1995): 163-199.

Apps, Jerry. Breweries of Wisconsin. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1992.

Baldwin, William O. “Historical Geography of the Brewing Industry: Focus on Wisconsin.” Ph.D. diss., University of Illinois, 1966.

Cochran, Thomas C. The Pabst Brewing Company: The History of an American Business. New York: New York University Press, 1948.

Gurda, John. Miller Time: A History of Miller Brewing Company, 1855-2005. Milwaukee: Miller Brewing Company, 2005.

Mittelman, Amy. Brewing Battles: A History of American Beer. New York: Algora, 2007.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.