Beginning in rustic boardinghouse barrooms serving straight whiskey and lively conversation and evolving into multi-million dollar night clubs with state-of-the-art sound systems entertaining finely-attired patrons, nightlife in Milwaukee has changed considerably as the city has grown and its population has diversified. Nightlife—the after-dark pursuit of entertainment, liquor, social mixing, romance, and sex—is an essential aspect of the city’s cultural fabric. Historically, Milwaukee’s nightlife exhibited the kinds of racial and class restrictions that appeared in the city’s social order as a whole. However, there have also been examples of deviation from these norms in Milwaukee’s nightlife, places where the races mingled, where women drank in the company of men, and where homosexual men and women could meet—all before these ideas were widely accepted socially.

After-dark entertainment in early Milwaukee consisted primarily of downing whiskey—and beer when it first arrived in the village sometime after 1839[1]—at any number of small “rum holes” located along the Milwaukee River. Most of these places catered to traveling laborers and offered overnight lodgings. Some of the best-known of these early places were the Shanty Inn, along the west bank of the Milwaukee River, and the Triangle Inn, located at Water and Huron (now Clybourn) streets, which is believed to have been the area’s first tavern.[2] Robert Wells, in This Is Milwaukee, cites the Third Ward’s Milwaukee House, which featured a bar and a two-piece band, as “the center of [early] Milwaukee’s swinging night life.”[3]

It seems that these early night spots were reserved for men only. However, by the late 1840s, dance halls offered chances for the sexes to intermingle, drawing some of the earliest known moral objections to after-dark entertainment. In 1849, the Milwaukee Sentinel complained of the growing popularity of polka dancing in city dance halls, claiming it required a man and woman to “vigorously rub themselves together.”[4] By the 1850s, Milwaukee alderman passed a resolution asking the city attorney to begin prosecuting “houses of ill-fame,” the era’s euphemism for a house of prostitution.[5] Soon after these early mentions of vice in Milwaukee, the Sentinel took a public stand against dancehalls that operated on the Sabbath. Sunday dancing and late-night revelry were “outrages upon religion, law, and order,” the paper claimed, calling on the Common Council to take action on the matter.[6]

While the Common Council seemed unable or unwilling to crack down on places where prostitutes plied their trade, they did engage in a prolonged battle against Sunday dancing. In 1862, Mayor Horace Chase signed a Sunday dancing ban that, per the Sentinel, was soundly backed by the citizenry.[7] The ban proved difficult to enforce, however, with many dancehalls favored by Germans ignoring the orders. Again, the mixing of the sexes was a major point of contention in the battle over Sunday dancing. The Sentinel, which supported the ban, claimed a definite link between female attendance at dance halls and prostitution.[8] Despite the best efforts of the moralists, the Sunday ban was thrown out by a city judge in 1870.[9]

By the end of the Civil War, saloons and taverns were operating in all corners of the city. Also by this time, an area west of the Milwaukee River in downtown—which eventually became known as the “Badlands”[10] —had gained an unsavory reputation that it carried for more than a century. As early as 1858, police had raided brothels in the area and, by 1862, the German-language press was calling for action to stop prostitution in the area, which was being conducted more and more openly.[11] Over the next two decades, brothels in the downtown area along the river numbered as many as 95, with little objection from the police department.[12]

Racial issues also began to affect public policy on nightlife in the 1880s. A string of rowdy saloons in the Badlands near the intersections of Wells Street and Second and Third streets was called “Brown Row” or “Nigger Alley” by the Sentinel, a crude reference to the interracial patronage to which these places catered.[13] The complexion of a bar’s patronage was a significant factor in its dealings with city officials. An 1884 raid on brothels ignored the whites-only houses but arrested everyone found in the houses of Brown Row.[14] That same year, when the first liquor license ordinance went into effect, several places were denied the permit because they allegedly served black customers of “low-character” or allowed black men to dance with white women.[15]

In 1888, the idea of Milwaukee as “wide-open city” emerged with the appointment of John Janssen as police chief. Under Janssen, the periodic raids on downtown brothels and low-class saloons was stopped.[16] The election of David Rose in 1898 gave the wide-open city concept a champion in the mayor’s office as well. Nicknamed “All the Time Rosy,” the mayor campaigned on the promise of running “a Live Town” bursting with carnivals, conventions, and nightlife. The brothel district Rose inherited became a local institution, and gambling halls, like the one above the Marble Hall tavern on Broadway, served some of the city’s most esteemed residents.[17]

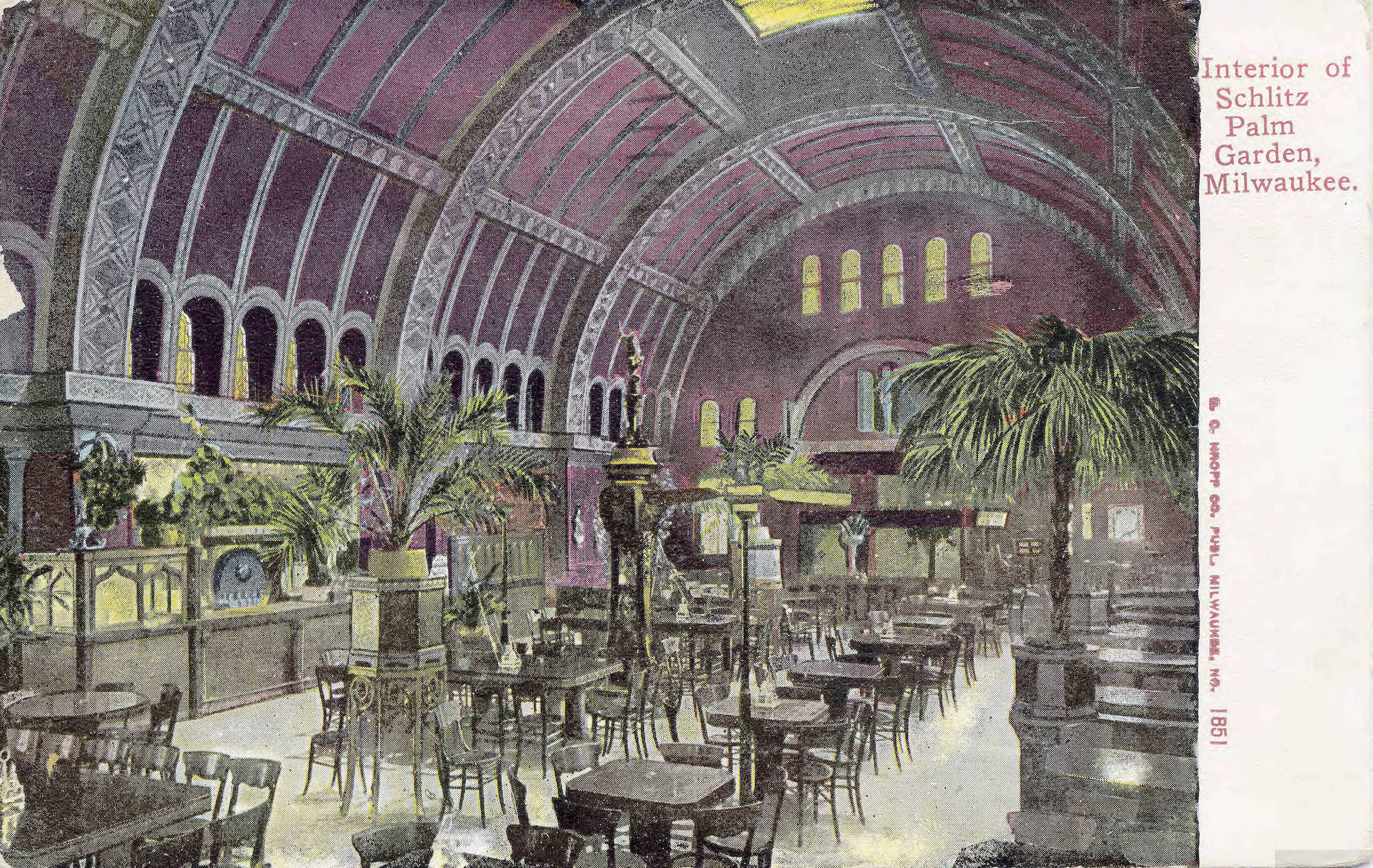

Yet even in the age of “All the Time Rosy,” not all of Milwaukee’s nightspots operated outside the law. Grand Avenue (now West Wisconsin Avenue), was home to a number of restaurants and bars that drew respectable Milwaukeeans. The Schlitz Palm Garden, attached to the Schlitz Hotel on North Third Street, featured fine food, live music, and dancing. The College Inn on North Second Street featured Hawaiian music and was a gathering place for actors passing through town on the live theater circuit.[18]

By 1910, it seemed that the wide-open city concept had fallen out of favor with Milwaukee voters. A clamor for reform and regulation swept the city, and Socialists took control of the mayor’s office, the Common Council, and nearly two dozen other city and county posts. Among the Socialists’ campaign pledges was shutting down the all-night gambling dens, dive bars, and brothels that had come to define the city after-hours.[19] The most visible of these reforms occurred in June 1912, when Socialist District Attorney Winfred Zabel ordered madams in the city to close up their shops or face arrest.[20]

The order made big news, but a state investigation into vice conditions in Milwaukee in 1913 found the prostitution trade in the allegedly shuttered district to be operating as openly as ever.[21] The investigation also found the worst conditions to be in the Badlands. Here, prostitutes worked in a number of cheap taverns and hotels and even in more “respectable” establishments like the Schlitz Palm Garden and the Dreamland Dance Hall on Wells. A number of places also employed female singers who specialized in “smutty songs” and “vulgar” dances. The Edward Howard Saloon on North Fourth Street and the nearby Upton Hotel were known for entertainment of this sort, and for allowing their entertainers to solicit men in the audience after their shows.[22]

Reform-minded Socialists had little success in stopping Milwaukee’s illicit nightlife in the 1910s, and in the 1920s, Prohibition did not fare much better. The passage of the Volstead Act in 1919 officially put Milwaukee’s entire roster of bars and taverns on the wrong side of the law, but revelers soon found ways around the new restrictions.

While illegal booze and beer was easy to acquire in most parts of the city, two areas stood out as major speakeasy districts during the age of Prohibition.[23] The first was the Third Ward neighborhood, Milwaukee’s “Little Italy.” The Third Ward was an area unknown to most Milwaukeeans before Prohibition. According to a 1927 Milwaukee Journal article, the early years of Prohibition in Milwaukee were a cautious time, with few examples of the unbridled revelry of the David Rose days. It was not until the city discovered the ample supply of home-brew beer and grape wine in Third Ward speakeasies that the Twenties began to roar in Milwaukee. With money flowing into the neighborhood, glamorous venues with raucous jazz music and all-night dancing catered to the city’s social elite. The Monte Carlo club, 171 Detroit Street (now East St. Paul) was one of the Ward’s hottest spots and was one of a number of clubs in the area operated by men associated with Milwaukee’s criminal underworld. By the late 1920s, the area was known as the city’s “Cabaret District.”[24]

The other major speakeasy district was in an area familiar to both partiers and policemen. A stretch of West Wells Street—running through the heart of the Badlands—was known as “Gin Alley” during Prohibition.[25] A raid by federal Prohibition agents on the area in 1931—noted as the largest such raid in the city’s history—revealed at least 22 illegal bars in a cluster of blocks between the Milwaukee River and North Fifth Street.[26] A significant speakeasy district also developed in rural areas of the county, with many illegal roadhouses lining Bluemound Road.[27]

A raid a few days later at the Melody Club at 704 Highland Avenue revealed that in certain areas of the city black and white Milwaukeeans were visiting the same nightclubs. The Sentinel described the Melody Club as a “black and tan,” meaning a place that drew a mixed-race crowd and often employed African American musicians.[28] The concept was still offensive to some, and the reactions of city authorities reflected this.[29] A few years later, after Prohibition had been repealed, a group of Milwaukee clergymen made a series of allegations on the nightlife scene in the city, warning of clubs and bars in which mixed-race pairs danced and drank together.[30]

While African American Milwaukeeans were excluded from most of the city’s nightlife, residents of the Bronzeville neighborhood developed their own entertainment district, with vibrant clubs, music halls, and bars. According to Milwaukee’s Bronzeville, by Paul H. Geenen, in the 1920s, the Metropole became the first Bronzeville club to gain wide popularity. Thelma’s Back Door (701 West Juneau Avenue) and the Polk-A-Dot (1352 West Lloyd Street) also became hotspots for jazz, drinks, and dancing. The Flame on North Ninth and the Moon Glow on North Seventh were two of the neighborhood’s most popular clubs.[31]

The Bronzeville entertainment district was also on the so-called “Chitlin’ Circuit” of Midwestern cities that hosted nationally-known African American bands and singers through the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s.[32] Louis Armstrong, Billie Holliday, Nat King Cole, and Dizzy Gillespie all performed in the neighborhood.[33] After their shows, many Bronzeville entertainers headed to the Casablanca, the neighborhood’s well-known after-hours club run out of an old mansion which had been converted into a boarding house at 1641 North Fourth Street.[34]

With the increasing popularity of jazz music, black and tan clubs became some of the city’s most attractive bars and music venues. By the mid-1950s, the Flame and the Milwaukee Club were both billing themselves as “black and tans,” advertising prominently in local papers and boasting of their “all-sepia” reviews and talent.[35] By the late 1950s, a wide variety of nightclub acts could be found in Milwaukee. The Club Terris (531 West Wells Street) boasted of their “All Star Girl Revues.” The Cackle Shack on West Vliet was the “Home of Western Music.” Thelma’s Back Door—another black and tan—featured calypso music and dining. The Nightingale Ballroom on Highway 145 in Menomonee Falls was home to polka and big band music. The Pink Poodle on Highway 100 in Greenfield even promoted their bartender as an entertainer, urging people to come see “Lenny, our Mixologist Extraordinary.”[36]

The Club Terris was hardly the first club in Milwaukee offering burlesque and striptease dancing. Burlesque had been a staple of the city’s evening entertainment since the turn of the century, when the main attractions were actually the male entertainers—famous athletes or bawdy comedians—and the dancing females were presented as a show-closing chorus line. The women started to become the main attraction in the 1930s as the strip-tease aspect of burlesque emerged. Four major burlesque houses operated in the downtown theater district: the Empress and the Star Burlesque theaters on North Third, and the Gayety and Considine theaters on North Third and North Second, respectively. The Empress was the last of these houses to close, doing so in 1955.[37]

Despite the variety of big names attracted to Bronzeville, most of the early 1960s discussion of nightlife in Milwaukee focused on how poorly it compared with other similarly-sized cities. Factors like the city’s proximity to Chicago, its numerous neighborhood bars, and the traditional “Teutonic conservatism” of its citizenry were all offered as reasons for the city’s lack of a major nightclub district.[38] In the late 1960s, however, the Milwaukee Journal noted that nightlife in Milwaukee was experiencing a “comeback.” The Safe House on Front Street opened in 1966, with a spy theme so novel that it was featured in TIME magazine. The Nauti-Gal, 611 Milwaukee Street, was billed as a “Playboy Club-style” lounge with waitresses in skimpy dress who also danced and sang between serving customers. And the Crown Room, on the 23rd floor of the Pfister Hotel, became one of Milwaukee’s first high-rise nightclubs.[39]

The late 1960s also saw Milwaukee nightclubs reach out to younger audiences. Jazz clubs became go-go strip joints. Big band music was replaced with rock shows. Downtown clubs like the Scene, the Attic, and Penthouse all regularly featured rock-n-roll acts. [40] At O’Brads on East Locust Street, young people and students showed off the latest in mod fashions at the city’s only psychedelic rock club.[41] College students were certainly a part of these crowds and also frequented bars nearby to their home campuses. Marquette students favored Wells Street bars like O’Donoghue’s and the Avalanche.[42] The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee bar scene was much slower to develop but eventually grew to center on North Avenue.[43]

Issues of race and sex continued to play a role in the city’s nightlife. Many Milwaukee club owners cited the Civil Disorder of 1967 and the protests that followed as a reason some Milwaukeeans would not venture downtown after dark.[44] This decline in the image of downtown continued through the 1970s, as the reputation of the old Badlands area spread to West Wisconsin Avenue. By the mid-1970, sex was the leading industry in downtown after dark—in the X-rated films now favored by Wisconsin Avenue’s movie theaters, the adult book stores and arcades, and the very visible presence of prostitutes.[45]

Also operating on the fringes of social acceptability for the time was Milwaukee’s burgeoning gay nightlife. Early gay bars in the city were highly discreet. The Royal Hotel Bar (546 East Michigan) was a secret hangout for gay men as early as the 1930s.[46] The Mint Bar (422 West State Street) opened in 1949 and was, according to the Milwaukee LGBT History website, “an early beacon for gay men in Milwaukee.”[47] The first openly gay bars began to appear in the 1960s.[48] The River Queen (402 North Water Street) was one of the first, opening in the early 1960s. Nite Beat (196 South Second Street) opened around 1964 and was one of the earliest lesbian bars in Milwaukee.[49] Despite a significant growth in the number of gay bars in Milwaukee over the next decade-plus, it was not until 1984, when Le Cage Aux Folles opened at 801 South Second Street, that one had windows open to the street.[50]

Le Cage opened as a dance club, following a trend which had begun in the late seventies with the disco craze. In 1978, the Journal reported that Milwaukee clubs were imitating the discos of New York City, with strict dress codes, high cover fees, and expensive drinks.[51] The Sand Dollar in Franklin and the Planet Circus on South Second Street (which catered to both straight and gay customers[52]) were two popular spots. The operators of the Park Avenue (500 North Water Street) saw their club as the Studio 54 of Milwaukee. [53] This location also sought the business of Milwaukee’s gay men, reserving Sunday nights as “gay nights.”[54]

By the 1980s, a small nightclub district had formed along Broadway between Wisconsin Avenue and the Third Ward, mostly spurred by the disco boom. But the overall downtown nightlife scene was as quiet as ever. Development west of the river—like the Grand Avenue Mall—helped to increase traffic in the area during the day but had brought with it a spirit of urban renewal that chased away any remnants of the Badlands nightlife. The bookstores were closed, the surviving theaters dropped their X-rated programming, and a new anti-loitering ordinance chased away the area’s streetwalkers. The people drawn to the area because of these things stopped coming, and the people who had been scared off by such things did not come back. In 1984, the Journal declared, “They still roll up the sidewalks on Wisconsin Ave. after the sun sets,” and suggested that nightlife of any kind in the area might never return.[55]

Dance clubs have remained a constant in Milwaukee’s nightlife since the time of disco. A 1994 Journal article found that the dance scene was still vibrant but also remained fairly segregated. While whites made up the vast majority of patrons at east side and downtown clubs, African Americans accounted for nearly the entire crowd at clubs on the near-north and west sides of the city.[56] The small nightclub district that came in with disco remains mostly intact, with most clubs in the east-of-the-river part of downtown. But recent years have also seen a number of clubs opening up in Walker’s Point, the Third Ward, and other parts of the city.[57]

While Milwaukee’s nightlife has not been considered a major selling point of the city since the “wide open city” days of the 1890s, its after-dark entertainment has both reflected the traditional nature of its citizens and offered safe spaces for the city’s marginalized groups. And while nightlife in the city has long been at least subtly driven by sexual desires, it also reflects Milwaukee’s need for self-expression, social interaction, and for a way to get away from the daily pressures of adult life and simply relax.

Footnotes [+]

- ^ H. Russell Austin, The Milwaukee Story: The Making of an American City (Milwaukee: The Journal Company, 1946), 67.

- ^ Robert Wells, This Is Milwaukee (Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Company, 1970), 29.

- ^ Wells, This Is Milwaukee, 31.

- ^ “The Polka,” Milwaukee Sentinel, February 8, 1849, p. 2.

- ^ “Resolutions of Common Council,” Milwaukee Sentinel, February 16, 1850.

- ^ “Rip Van Winkle Waking Up,” Milwaukee Sentinel, March 16, 1850, p. 2.

- ^ “An Ordinance against Sunday Dancing,” Milwaukee Sentinel, November 11, 1862, p. 1.

- ^ “Sunday Dancing Still Lawful,” Milwaukee Sentinel, April 22, 1863, p. 1.

- ^ “Salutary Religion,” Milwaukee Sentinel, June 29, 1870, p. 2.

- ^ “Blacks Arrived in Late 1800s,” Milwaukee Journal Accent, February 6, 1979, p. 1.

- ^ “Descent upon Another Villainous Place,” Milwaukee Sentinel, August 6, 1858; “Houses of Ill-Fame,” Milwaukee Sentinel, August 22, 1862.

- ^ “A Police Raid,” Milwaukee Sentinel, April 30, 1882; John Janssen testimony, Transcript #3, p. 36, Unidentified City folder, box 19, Teasdale Vice Commission Files, Wisconsin, Legislature: Investigations, 1837-1945, Series 173, Wisconsin Historical Society archives, Madison, WI.

- ^ “A Police Raid,” Milwaukee Sentinel, April 30, 1882; “The Black List,” Milwaukee Sentinel, July 1, 1884.

- ^ “Raided by Police,” Milwaukee Sentinel, August 5, 1884.

- ^ “The Black List,” Milwaukee Sentinel, July 1, 1884.

- ^ John Janssen testimony, Transcript #3, p. 36, Unidentified City folder, box 19, Teasdale Files.

- ^ Austin, The Milwaukee Story, 161, 162, 164-165.

- ^ Richard Davis, “Those Bright Spots of Old,” Milwaukee Journal, September 2, 1951, p. 19.

- ^ “Remember When?” Milwaukee Journal, February 20, 1979; James John Bergman, “From River Street to Every Street: The Termination of Milwaukee’s Segregated Vice District” (Master’s thesis, Marquette University, 1984), 16.

- ^ “Milwaukee’s Vice District Is No More,” Milwaukee Journal, June 16, 1912.

- ^ Gerald McDonald testimony, “Hearing Before Committee,” p. 29, Unidentified City folder, box 19, Teasdale Files; JR Wolf testimony, “Hearing Before Committee,” p. 24, Unidentified City folder, box 19, Teasdale Files; “Corner of North & Lisbon,” folder Manuscript Investigator Reports pp. 538-839, box 21, Teasdale Files.

- ^ AC Wurth testimony, Transcript #2, p. 130, Unidentified City folder, box 19, Teasdale Files; “Report on Tyroler Han,” Manuscript Investigator Reports pp. 538-839 folder, box 21, Teasdale Files; “Report on Schlitz Saloon,” Manuscript Investigator Reports pp. 1-238 folder, box 21, Teasdale Files; “Report on Edward Howard Saloon,” Manuscript Investigator Reports pp. 1-238 folder, box 21, Teasdale Files; “Report on Upton Hotel,” Manuscript Investigator Reports pp 284-537 folder, box 21, Teasdale Files.

- ^ Austin, The Milwaukee Story, 185.

- ^ “Nightlife Glory of Milwaukee’s Third Ward Has Departed,” Milwaukee Journal, October 22, 1927, p. 3.

- ^ “Pajamas Fail to Prevent Dry Raid,” Milwaukee Journal, December 13, 1932, p. 1.

- ^ “Dry Army Swoops upon City,” Milwaukee Sentinel, January 7, 1931; “Believe It or Not, the City is Spotless; All Are Dark,” Milwaukee Sentinel, January 7, 1931, p. 3; “38 Liquor Raid Captives go to Federal Bldg,” Milwaukee Journal, January 7, 1931, p. 1.

- ^ Linda McAlpine, “Memories of Prohibition in Our Era,” Gmtoday website, posted November 26, 2008, accessed July 22, 2015.

- ^ “Drys Raid Golden Pheasant,” Milwaukee Sentinel, January 9, 1931, p. 1.

- ^ “Drys Raid Golden Pheasant.”

- ^ “Pastors Tell of Drunken Girls, Boys,” Milwaukee Journal, October 29, 1937, p. 1.

- ^ Paul H. Geenen, Milwaukee’s Bronzeville: 1900-1950 (Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2006), 57, 64.

- ^ Geenen, Milwaukee’s Bronzeville, p. 57.

- ^ “What Is Bronzeville?” Milwaukee Bronzeville blog, posted May 10, 2007, accessed May 2, 2015.

- ^ Geenen, Milwaukee’s Bronzeville, 70.

- ^ Jim Koconis, “Milwaukee Nite Life Chatter,” Milwaukee Sentinel, May 15, 1954, p. 9; “The Parade of Stars This Week at the Clubs,” Milwaukee Sentinel, May 15, 1954, p. 9.

- ^ “The Parade of Stars This Week at the Clubs,” Milwaukee Sentinel, April 12, 1957, p. 9.

- ^ Jay Joslyn, “Burlesque: The Word Evokes Memories of Old Milwaukee,” Milwaukee Sentinel, December 27, 1966, part 2, p. 6.

- ^ Michael Drew, “Milwaukee Night Life Booms as Patrons Pack New Clubs,” Milwaukee Journal Green Sheet, February 22, 1967, p. 1.

- ^ “Milwaukee Night Life Booms as Patrons Pack New Clubs.”

- ^ Michael Drew, “Jazz Club or Parking Lot?” Milwaukee Journal Green Sheet, October 10, 1967, p. 1.

- ^ Michael Drew, “Music of the Old Country Helps Little Bars Flourish,” Milwaukee Journal Green Sheet, October 12, 1967, p. 1.

- ^ “Digging up Wells Street’s Storied Past,” Marquette Wire website, published April 28, 2009, accessed July 18, 2015.

- ^ Evan Rytlewski, “Reshaping North Avenue in UWM’s Image,” Shepherd Express, February 11, 2010.

- ^ “Jazz Club or Parking Lot?”

- ^ Michael Drew, “A Small Town? Image Lingers,” Milwaukee Journal, July 3, 1974, p. 1.

- ^ “Michelle’s Club 546,” Milwaukee LGBT History Site, last updated September 2009, accessed May 4, 2015.

- ^ “Mint Bar,” Milwaukee LGBT History website, last updated December 2009, accessed May 1, 2015.

- ^ “Bars and Clubs in Wisconsin,” Milwaukee LGBT History website, last updated January 2007, accessed April 25, 2015.

- ^ “Nite Beat,” Milwaukee LGBT History website, last updated January 2008, accessed May 20, 2015.

- ^ “Le Cage Aux Folles,” Milwaukee LGBT History website, last updated October 2009, accessed May 12, 2015.

- ^ “Disco More than a Flash in the Pub,” The Milwaukee Journal, September 22, 1978, https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1499&dat=19780922&id=7m0aAAAAIBAJ&sjid=likEAAAAIBAJ&pg=6581,1195052&hl=en., last accessed May 2015.

- ^ “Planet Circus,” Milwaukee LGBT History website, last updated December 2006, accessed May 1, 2015.

- ^ Anthony Carideo, “Roaring Twenties Party Roared to Disco Beat,” Milwaukee Journal, February 15, 1979, p. 5.

- ^ “Park Avenue,” Milwaukee LGBT History website, last updated, December 2005, accessed May 1, 2015.

- ^ Damien Jaques, “Sun Down, Sidewalks Up,” Milwaukee Journal, October 1, 1984, p. 1.

- ^ Nick Carter, “Nightclubbin’,” Milwaukee Journal Weekend Life, March 31, 1994, p. 1.

- ^ “Dance Club Guide,” OnMilwaukee website, last updated April 15, 2011, accessed May 20, 2015.

For Further Reading

Bergman, James John. “From River Street to Every Street.” Master’s thesis, Marquette University, 1984.

Geenen, Paul. Milwaukee’s Bronzeville: 1900-1950. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2006.

Prigge, Matthew J. “Milwaukee Vice: Where the Action Was.” Shepherd Express, August 8, 2012.

Wells, Robert. This Is Milwaukee. Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Company, 1970.

Wisconsin LGBT History Project website.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.