Festivals have long been a major part of the cultural, social, and economic fabric of Milwaukee. Early festivals were often celebrations of a shared ethnic heritage. As the turn of the century approached, city leaders recognized the potential of these events to draw visitors from across the nation, and Milwaukee began to emerge as a leading center for “merry-making.”[1]

By the time of the Great Depression, the origins of Milwaukee as “the City of Festivals” emerged and the lakefront played host to a number of major celebrations. However, the “City of Festivals” concept truly emerged following the turmoil and rapid change of the post-war years. Starting in the late 1960s with Summerfest, and growing throughout the following decades with the creation of annual ethnic and neighborhood festivals, the long-time tradition of the Milwaukee festival became major factors in the city’s identity and economy while continuing to allow the city’s ethnic communities a chance to share and celebrate their heritage.

Historian Victor Greene traced Milwaukee’s festival history to the influx of German immigrants in the 1840s and 1850s, who brought such celebrations with them from the old country.[2] Notices of church and fraternal organization festivals appear in Milwaukee newspapers as early as the 1850s.[3] In 1862, the Milwaukee Sentinel noted that a recent spate of festivals had proven very successful in raising money for social and church groups. Few details of these festivals were given, but it was mentioned that they typically included music and refreshments.[4] The most significant festival of this era was probably the 1865 fundraising fair that helped to build the Soldiers Home (officially called the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers) on Milwaukee’s western edge. The centerpiece of the event was a raffle that gave away everything from agricultural products to a piano valued at $2,000.[5]

Festivals were widely adopted by a variety of groups, including those like the Independent Order of Good Templars—a temperance society—whose celebrations contrasted markedly with those of the freely-imbibing Germans.[6] While the early festival scene was dominated by German groups, Greene writes that these events were seldom exclusionary, and that people of all ethnic backgrounds enjoyed the German festivals.[7] Indeed, as the Sentinel noted in October 1890, attendees at the German-American Day celebration were “‘Yankees’ who knew no German [and] men from the Fatherland who knew little else.”[8]

The 1890 German-American Day festival stands out as one of the first Milwaukee festivals to attract national attention. The event celebrated the bicentennial of German migration to the New World and received attention from newspapers as far away as San Francisco.[9] A parade featuring eighteen floats represented Milwaukee business and industry and historical milestones in German history. Six white horses where loaned by Captain Frederick Pabst to lead the parade. The Sentinel estimated that 100,000 people took part in the festivities or watched the parade as it marched down Wisconsin Avenue and into Walker’s Point. The participants enjoyed music and food and a series of speeches from local dignitaries, in both German and English. The event was not only an outpouring of German pride but also a showcase for Milwaukee. The national media attention given to the festival and the participation of business leaders showed that Milwaukee’s festivals were beginning to evolve as something more than simple fundraisers or chances for locals to enjoy an afternoon of recreation. The Sentinel even expressed hope that Milwaukee could become a national leader in such celebrations.[10]

Greene found that these early festivals were often used to boost local pride and increase the national visibility of Milwaukee as a recreational destination, which is evidenced in the participation of local industrialists, particularly Frederick Pabst, who donated over $2,000 of his own money to the German-American Day festival.[11] Greene also found that these festivals often fostered ethnic pride while at same time promoting the Americanization of recent immigrants.[12] “Groups could continue to broadcast ethnic cultures,” he wrote, “instead of abandoning them while becoming Americans.”[13]

A major multi-ethnic festival was held in May 1896. Modeled on the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, the “Bazaar of All Nations” proved so popular with both locals and visitors that its initial eight day schedule was expanded to ten.[14] Held at the Exposition Building on Kilbourn Avenue, it showcased the native dress, music, food, and dance of thirteen nations. A total of 26,000 tickets were purchased, raising more than $15,000[15] for the construction of the Civil War monument that today sits at the intersection of Tenth Street and Wisconsin Avenue.[16]

With the rise of the Socialist Party in local politics, Greene writes, city-sponsored festivals became less about ethnic celebration than they did about providing the city’s working classes a chance for recreation.[17] Festivals became smaller affairs and often took place in public parks and playgrounds.[18]

The global outbreak of war in 1914 again shifted the focus of local festivals. After the United States entered the war, a series of “Americanization pageants” was held, featuring unabashed patriotism and new citizen swearing-in ceremonies.[19]

In the years after the war, festivals in Milwaukee reverted to fairly low-key events, held at playgrounds and parks or as church or neighborhood events.[20] The idea of the festival as a major event, held with an intention of boosting Milwaukee’s national profile, returned in the 1930s. On a trip to Europe in 1931, Mayor Daniel Hoan had been impressed with the all-city festivals he had seen.[21] On April 17, 1933, a major festival was held at the Milwaukee Auditorium celebrating the end of national Prohibition. The event was promoted as a traditional German “volkfest,” but was quickly dubbed by the Milwaukee Journal as “Beer Fest.” A crowd of over 20,000 filed through the building, sampling traditional German food and drinking more than 35,000 glasses of beer. “I am happy that all of us thirsty are here for a sample of Milwaukee hospitality,” Hoan told the crowd.[22]

The boisterous music—provided by six live bands—and the free-flowing beer and plentiful food of “Beer Fest” foreshadowed more modern Milwaukee festivals.[23] A few months later, in July 1933, another step toward modern festivals occurred when the first major city-sponsored festival was held on the lakefront. A Milwaukee homecoming festival drew more than 100,000 visitors to the lakefront and was highlighted by Harvest Festival of Many Lands,[24] which was incorporated into the Homecoming event after starting out as a playground festival in 1927. The Harvest presentation featured the traditional dress, dance, and music of various ethnic groups and was already a popular event in its own right by the time it moved to the lakefront.[25]

The summertime lakefront festival eventually became an annual event, known as the Midsummer Festival. With the popularity of the 1933 events, the city began to see the festival as a chance to build an event that fit Milwaukee’s character and could become as much a part of the city’s identity as was the Festival of Roses in Pasadena or Mardi Gras in New Orleans.[26] In addition to the Harvest Festival dances, the festival featured everything from carnival entertainment to operas to plays to motorcycle exhibitions.[27] The event continued to grow until the United States was drawn into the Second World War. Planners trimmed the 1942 event from nine days to seven and eventually canceled it.[28] It was canceled again in 1943 and eventually discontinued.[29]

One of the ethnic celebrations included in the Midsummer Festival did survive, however. The pageant of old country dress, dance, and crafts survived as the Holiday Folk Fair, which was held at an auditorium in the Public Service Building beginning in 1943. The Folk Fair moved to the MECCA in 1974 and grew to draw about 60,000 visitors annually. It later moved to State Fair Park.[30]

Despite the modest popularity of the Folk Fair, the first decades of the post-war era would see an abandonment of the idea that a festival of national import could be based in Milwaukee. But as the decades following the end of World War II presented a host of radical changes and great challenges for the city, it was once again a mayor’s trip abroad that sparked interest in a defining Milwaukee festival. Mayor Henry Maier, elected in 1960, had been inspired by the great festival he had seen in Munich during a trip there in 1961.[31] The following year, a committee appointed by Maier to study the possibility of a major summertime festival recommended that the city go forward with a program featuring a folk fair, a series of jazz concerts, a film festival, and an “ideas conference” featuring “the finest minds of the day.”[32]

The recommendations of the committee lingered, however, until the civil disorder of 1967 left city officials searching for a way to repair Milwaukee’s tarnished image. Maier pushed the festival as a way to “show that Milwaukee is not the city of the clenched fist, but rather the city of the outstretched hand of friendship.” The festival was set for July 1968 and was to be held at the lakefront and various other sites across the city. The proposed name for event, “Juli Spass” (German for “July Fun”) was criticized as being exclusionary of other ethnic groups. The replacement title, “Summerfest,” stuck.[33]

The first Summerfest was not unlike the event Maier’s committee had proposed five years earlier. While it included many live music acts and a carnival-style midway, it also featured athletic competitions, cultural fairs and displays, a United Nations-sponsored conference on “women’s progress,” and a number of events focused on the arts—including a film festival, live theater, and a tribute to Walt Whitman. There were also several programs aimed at African Americans, the first time any city-wide festival had focused on black culture, dance, and music.[34]

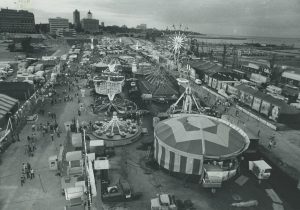

This original vision of Summerfest as a varied festival of music, culture, and the arts would quickly give way to a more straightforward program of nationally-known entertainers. In 1970, Summerfest concentrated its events on a strip of lakefront that had previously been used as an airstrip and a Nike anti-aircraft missile base. Concerns that the festival was becoming too youth-oriented and might become “another Woodstock” drove organizers to gravitate towards more “middle-of-the-road” acts in 1973.[35] As the event began to drawn nation attention, Maier was certain that it would continue to grow into a major part of the city’s identity and an international destination. “This can be THE world festival,” Maier told the Sentinel.[36]

In the wake of Summerfest’s success in the 1970s, Milwaukee’s Italian community sought to reestablish the traditional neighborhood festivals that had been held in the Third Ward.[37] These street celebrations had emerged there in the early 1900s,[38] but had faded with the slow removal of the residential portions of the Third Ward in the post-war era. The result of their efforts was Festa Italiana, first held in August 1978.[39] It was held on the same patch of lakefront ground as Summerfest and revived another long-lost tradition with a grand procession of religious statutes and idols which were paraded through the old Italian colony and to the festival grounds. The Festa procession was held on the final day of the festival, a Sunday and culminated with a public mass at the lakefront grounds.[40]

While Festa Italiana revived decades-old traditions, Milwaukee’s Mexican community’s street festival tradition was just four years old when it moved to the lakefront in 1977. Mexican Fiesta featured traditional Mexican music, dance, and food. The event was established both as a means of celebrating Mexican culture and also for funding the Wisconsin Hispanic Scholarship Foundation.[41]

Following the lead of the Italian and Mexican communities, other ethnic groups jumped on the festival bandwagon. Plans for an Irish festival were hatched in 1979 by the area’s Shamrock Club.[42] The event was seen as a way to both preserve cultural heritage and promote cultural awareness among young people.[43] Irish Fest was launched in 1981 and eventually established itself as the largest of Milwaukee’s ethnic festivals and the largest celebration of Irish culture in North America.[44]

German Fest also debuted in 1981, eagerly backed by Mayor Maier, who promised that Milwaukee’s festival would “make Munich jealous.”[45] For most of the 1980s, German Fest trailed only Festa Italiana in terms of popularity.[46] While featuring festival staples like traditional food, music, and dance, German Fest added a Sheepshead tournament—the card game long adored by Milwaukee’s German residents—in 1987.[47]

In 1982, claiming such an event was “long overdue,” members of Milwaukee’s Polish community launched Polish Fest. Features of the festival included a polka contest, a “Miss Polonia” beauty pageant, and, in 1984, a wrestling match pitting the “Polish Eagle” against the “Russian Bear.”[48] By 2000, it had become the largest celebration of Polish heritage in the United States.[49]

Reflecting on the development of the Lakefront festival season in 1981, Maier made it clear that he saw the festivals as a major part of Milwaukee’s post-war urban rebirth. “No great cities laid claim to renown,” he said, “without the essential ingredient of urban life—the festival.”[50] In 1983, Milwaukee’s identity as the “city of festivals” was cemented when the City of Festivals Parade debuted. The miles-long procession served as the kick-off event for Summerfest, as well as the neighborhood festival season. The parade’s organizers designed it to mimic the parades that opened the Rose Bowl and Fiesta Bowl college football games and hoped it would become a lasting and nationally-recognized event.[51] It would not, however, and was last held in 1993.[52]

Through the 1980s and 90s, as the lakefront festival season continued to grow, events were developed that were intended to serve as points of cultural pride for groups that had traditionally been marginalized in Milwaukee. Afro Fest was launched in 1983, with the help of local Civil Rights icons Vel Phillips and Lloyd Barbee. Afro Fest’s founder, Michael Brox, cited the need to help the black community’s young people as the main reason for launching the festival, but also made it clear that it would act as an important means of visibility for the community. “We had to be represented,” Brox told the Journal, “It’s a political statement, being on the Summerfest grounds.”[53] In 1989, the festival’s name was changed to African World Festival to better reflect an emphasis on black history and culture.[54]

The backers of the Indian Summer festival, which debuted in 1987, had similar goals for their event, which traditionally brings an end to the festival season at the lakefront grounds, which were named for Henry Maier in 1986. “The main thrust of Indian Summer,” an organizer told the Journal, “is a positive educational exchange with all people.” [55]

In the 1990s, PrideFest joined the summer lakefront festivals. The LGBT festival’s roots can be traced to 1988, when a week-long series of events was held culminating with a rally at Cathedral Square Park. In 1996, PrideFest moved from Veterans Park to Henry Maier Festival Park. In addition to music and food, PrideFest featured events unique to the festival season, such as AIDS testing and same-sex commitment ceremonies. Today, it bills itself as the world’s largest volunteer-operated LGBT festival with a permanent home.[56]

While the large lakefront festivals dominated the public’s attention, numerous other festivals have appeared since the 1960s. Two major ethnic festivals, Greek Fest and Bastille Days, are held at sites off of the lakefront. Greek Fest was held on the grounds of the Annunciation Greek Orthodox Church on the city’s west side for forty years before moving to the State Fair Grounds in 2006.[57] Bastille Days, a celebration of French culture, has been held annually since 1982 and currently is centered at Cathedral Square Park. It is recognized as one of the largest Bastille Day events in the United States.[58]

Meant as a cold-weather companion to Summerfest, Icebreaker debuted in January 1989 as a four-day indoor/outdoor festival that focused on winter sports, music, and comedy.[59] The concept was yet another backed by Maier, who had been advocating for a winter festival since the mid-1980s.[60] The event was renamed Winterfest in 1989 and had a modestly successful run until 1998, when it was cancelled.[61]

Today, Milwaukee continues to use its festivals as a major part of its national identity. The lakefront festivals draw over one and half million people annually and claim a $180 million impact on the city.[62] Yet, the social and cultural legacy of the city’s early festivals has not been lost. Just as with the early German folk celebrations, people of all backgrounds enjoy these festivals and learn about the cultural heritages they represent. While Americanization is no longer a goal of these events, festivals like the Asian Moon Festival or Arab World Festival—although neither is currently held—offered opportunities for more recently arrived ethnic groups to participate in a major part of ethnic culture in Milwaukee. Today’s smaller neighborhood festivals—such the Brady Street Festival, Center Street Daze, and various other community gatherings and block parties—continue the tradition of using the festival as a means of strengthening neighbor ties and fostering a sense of community while enjoying food, music, and good company.

Footnotes [+]

- ^ Victor Greene, “Dealing with Diversity: Milwaukee’s Multiethnic Festivals and Urban Identity, 1840-1940,” Journal of Urban History 31, no. 6 (2005): 827.

- ^ Greene, “Dealing with Diversity,” 823.

- ^ Milwaukee Sentinel, November 8, 1858, p. 1; Milwaukee Sentinel, December 28, 1859, p. 1; Milwaukee Sentinel, December 26, 1859, p. 1.

- ^ “The Festivals,” Milwaukee Sentinel, June 28, 1862, p. 1.

- ^ Jeff Beutner, “Soldier’s Home Raffle,” Urban Milwaukee website, July 1, 2014, accessed April 29, 2015.

- ^ “Good Templars,” Milwaukee Sentinel, August 21, 1860, p. 1.

- ^ Greene, “Dealing with Diversity,” 822.

- ^ “A Great Pageant,” Milwaukee Sentinel, October 7, 1890, p. 1.

- ^ “German Day,” Daily Alta California (San Francisco), October 7, 1890, p. 1.

- ^ “For a German Day,” Milwaukee Sentinel, October 5, 1890, p. 1; “A Great Pageant.”

- ^ “Capt. Pabst to Pay the Bills,” Milwaukee Sentinel, October 10, 1890, p. 3.

- ^ Greene, “Dealing with Diversity,” 821.

- ^ Greene, “Dealing with Diversity,” 823.

- ^ Greene, “Dealing with Diversity,” 827; “Closing Night’s Show,” Milwaukee Sentinel, May 17, 1896, p. 3.

- ^ “Closing Night’s Show.”

- ^ “Bazaar of All Nations,” Milwaukee County Historical Society website, accessed January 10, 2015.

- ^ Greene, “Dealing with Diversity,” 827.

- ^ Greene, “Dealing with Diversity,” 823.

- ^ Greene, “Dealing with Diversity,” 832.

- ^ Greene, “Dealing with Diversity,” 823.

- ^ “20,000 Surge into Auditorium for Beer Festival,” Milwaukee Journal, April 18, 1933, p. 1.

- ^ “20,000 Surge into Auditorium for Beer Festival.”

- ^ “20,000 Surge into Auditorium for Beer Festival.”

- ^ Greene, “Dealing with Diversity,” 835.

- ^ Greene, “Dealing with Diversity,” 834.

- ^ “Milwaukee: Our Festival,” Milwaukee Journal, July 19, 1935, p. 1.

- ^ “Fete to Open Next Saturday,” Milwaukee Journal, July 11, 1937, sec. 2, p. 3.

- ^ “Midsummer Festival to Run Only a Week,” Milwaukee Sentinel, November 22, 1941, sec. 2, p. 1.

- ^ Greene, “Dealing with Diversity,” 839.

- ^ John Gurda, Cream City Chronicles: Stories of Milwaukee’s Past (Madison: Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 2006), 185-186.

- ^ Linda Steiner, “Festival Visitors Polka in Rain,” Milwaukee Journal, August 15, 1981, p. 14.

- ^ “Major City Project Remains Incomplete,” Milwaukee Sentinel, March 29, 1972, p. 11.

- ^ “Major City Project Remains Incomplete.”

- ^ “Summerfest Schedule, 1968,” Children in Urban America Project website, Marquette University, accessed January 20, 2015.

- ^ Georgia Pabst, “Summerfest Grew up Building on Success,” Milwaukee Journal, June 24, 1977, Accent Section, p. 2.

- ^ Dean Jensen, “Fest Called World Event,” Milwaukee Sentinel, September 16, 1972, p. 5.

- ^ “History,” Italian Community Center website, accessed December 30, 2014.

- ^ Steve Quanrud, “Festa Italiana Rooted in Religion,” Milwaukee Sentinel Let’s Go!, July 17, 1981, p. 12.

- ^ “History,” Italian Community Center website, accessed December 30, 2014.

- ^ “Festa Italiana Rooted in Religion.”

- ^ “About Us,” Mexican Fiesta website, accessed January 10, 2015.

- ^ “Shamrock Club History,” Shamrock Club of Wisconsin website, accessed December 29, 2014.

- ^ Linda Steiner, “You Want to Take a Little Trip?” Milwaukee Journal, June 3, 1981, Accent section, p. 1.

- ^ “Irish Fest Hires Marketing Agency,” Milwaukee Business Journal, posted February 28, 2006, accessed January 10, 2015.

- ^ Linda Steiner, “Festival Visitors Polka in Rain,” Milwaukee Journal, August 15, 1981, p. 14.

- ^ Jay Joslyn, “Fests Flourish as They Unite Groups,” Milwaukee Sentinel, June 4, 1992, p. 1.

- ^ Tina Burnside, “It Was the Best of Times,” Milwaukee Sentinel, July 25, 1987, p. 5.

- ^ “Fest Celebrates Polish Life,” Milwaukee Sentinel Let’s Go!, August 31, 1984, p. 13.

- ^ Polish Fest advertisement, Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel, June 21, 2000, p. 2D.

- ^ Linda Steiner, “Festival Visitors Polka in Rain,” Milwaukee Journal, August 15, 1981, p. 14.

- ^ “Here Comes the Parade,” Milwaukee Journal, June 15, 1985, Entertainment Section, p. 1.

- ^ Jackie Loohauis, “City’s Great Promoter,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, February 3, 2001, http://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1683&dat=20010203&id=2bMaAAAAIBAJ&sjid=ojAEAAAAIBAJ&pg=6881,2050343.

- ^ Eugene Kane, “Grass Roots at the Heart of Afrofest,” Milwaukee Journal, June 30, 1983, Accent section, p. 1.

- ^ Eugene Kane, “Black Celebration Seeks New Spirit,” Milwaukee Journal, July 28, 1989.

- ^ Jaqueline Gray, “An Eye Opener,” Milwaukee Journal, September 11, 1988, p. 2B.

- ^ “History,” PrideFest Milwaukee website, accessed January 20, 2015.

- ^ Annysa Johnson, “Greek Fest Moves to State Fair Park,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, June 1, 2006, p. 3B.

- ^ “Bastille Days,” Easttown Association website, accessed January 21, 2015.

- ^ Tom Held and David Staats, “Officials Call Icebreaker a Hit,” Milwaukee Sentinel, January 30, 1989, p. 5.

- ^ John Higgins and Bob Kiesling, “Mayor’s Winterfest Idea Gets Initial Support, Milwaukee Sentinel, p. 5.

- ^ “It Was 15 Years Ago Today,” OnMilwaukee website, posted September 11, 2013, accessed January 19, 2015.

- ^ “Milwaukee World Festival, Inc. Fact Sheet,” accessed May 1, 2015.

For Further Reading

Greene, Victor. “Dealing with Diversity: Milwaukee’s Multiethnic Festivals and Urban Identity, 1840-1940.” In Perspectives on Milwaukee’s Past, edited by Margo Anderson and Victor Greene, 285-315. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2009.

Greene, Victor, “Dealing with Diversity: Milwaukee’s Multiethnic Festivals and Urban Identity, 1840-1940,” Journal of Urban History (31) 2005.

Gurda, John, Cream City Chronicles: Stories of Milwaukee’s Past, Madison: Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 2006.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.