Milwaukee’s downtown was anomalous compared to its peer cities over a good part of its historical evolution. This uniqueness was expressed most noticeably in its relatively small size, its weaker commercial function, and its tenuous relationship to the balance of the metropolitan area. Primarily because the city was eclipsed economically by nearby Chicago, Milwaukee rarely captured regional headquarters or banking and finance agglomerations, as was the case with typical American regional trade centers like Minneapolis and Pittsburgh. Rather, Milwaukee developed primarily as a production center where commercial interests were secondary.[1] The net product of these distinctions was that Milwaukee never developed a central business district truly reflective of its metropolitan scale.[2] The decentralization of retail to numerous smaller neighborhood-oriented centers in Milwaukee occurred earlier than in other American cities, further minimizing the downtown’s commercial function. For example, Schuster’s, the largest department store chain in the city for a good part of the twentieth century, had locations in numerous neighborhood retail corridors, but not a single store downtown.[3] While downtown Milwaukee was clearly the commercial center of the region, many historians and commentators noted that it lacked the hallmarks of a typical American downtown, including a concentration of tall buildings and a vibrant commercial atmosphere.[4] Interestingly, this comparatively minor role that downtown came to play echoed the city’s decentralized European-American beginnings where three “founding fathers” established three separate and competing pioneer villages on each side of the confluence of the Milwaukee and Menomonee rivers.

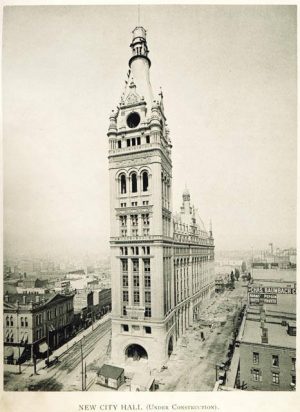

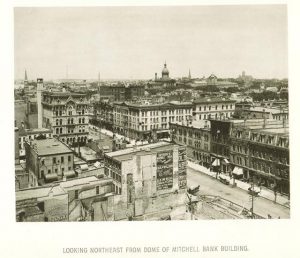

Milwaukee’s downtown enjoyed an exceptional concentration of late nineteenth century German-American architecture in both prominent private and public buildings. Although other American cities like Cincinnati and Saint Louis were noted for their German-American culture, only in Milwaukee was the ethnic German population so large and so dominant that it could inscribe its identity into the city’s downtown physical landscape. Visitors often commented on the city’s “foreign” appearance. Notable private buildings include the Pabst Building (1891), the Pabst Theater (1895), and the Germania Building (1896), all of which blended popular American architectural styles of the era with design motifs associated with Germany. The crowning edifice of this German-American landscape was Milwaukee’s unique Flemish-Renaissance City Hall (1895), modeled partly on the Hamburg Rathaus, from which Milwaukee’s Socialists ran the city for a half century.[5]

During the decades after WWII, however, national and global forces reshaped Milwaukee’s downtown into a central business district that is now typical of an early twenty-first century American city. Beginning with urban renewal and the building of the freeway system, and then progressing to the rise of historic preservation, New Urbanism, and gentrification, Milwaukee’s downtown currently mirrors its peer cities in both function and form. While generally still bereft of a strong retail agglomeration, downtown Milwaukee has emerged as a vibrant and high density, multi-use “live/work/play” neighborhood where residents have higher incomes and more education than the city-wide average. New upscale condominium and apartment construction, along with warehouse and office building repurposing, pushed downtown Milwaukee’s population to roughly 25,000 in 2015. More than $2.6 billion in private and public investment in the preceding decade produced an amenity-rich landscape dominated by museums, marketplaces, pedestrian corridors, and nightlife districts oriented to these higher-income residents, as well as the tourism and convention business. A final step in this normalization of downtown Milwaukee was evidenced by the relocation of ManpowerGroup Inc.’s corporate headquarters and the expansion of Northwestern Mutual Life Insurance Company’s downtown campus. Both developments increased the corporate and advanced service sector functions of Milwaukee’s downtown.[6]

Footnotes [+]

- ^ Joseph A. Rodriguez, Bootstrap New Urbanism: Design, Race and Redevelopment in Milwaukee (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2014), 3-4.

- ^ John Gurda, The Making of Milwaukee (Milwaukee: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 1999), 188.

- ^ Gurda, Making of Milwaukee, 330.

- ^ Rodriguez, Bootstrap New Urbanism, 4.

- ^ Steven Hoelscher, Jeffrey Zimmerman, and Tim Bawden, “Milwaukee’s German Renaissance Twice-Told: Inventing and Recycling Landscape in America’s German Athens,” in Wisconsin Land and Life, eds. Robert C. Ostergren and Thomas R. Vale (Madison, WI: The University of Wisconsin Press, 1997), 376-409.

- ^ Hunden Strategic Partners, Downtown Milwaukee Entertainment and Hospitality Comparative Analysis (2015), http://gmconline.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Final-Milwaukee-Downtown-Comparative-Analysis-5-18-15_reduced.pdf, now available at https://www.milwaukeedowntown.com/sites/default/files/content_blocks/files/Final-Milwaukee-Downtown-Comparative-Analysis-5-18-15_reduced_3.pdf, last accessed November 13, 2018.

For Further Reading

Ashwood, Patrick George. “Downtown Redevelopment, the Public-Private Partnership, and the Downtown Mall Solution: A Comparison of the Redevelopment Process in Minneapolis and Milwaukee.” PhD diss., University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 1991.

Campo, Daniel, and Brent D. Ryan. “The Entertainment Zone: Unplanned Nightlife and the Revitalization of the American Downtown.” Journal of Urban Design 13, no. 3 (2008): 291-315.

Dretzka, Ann E. “The Role of the City Center in a Dispersed Urban Community, Milwaukee.” PhD diss., University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 1974.

Kenny, Judith T., and Jeffrey Zimmerman. “Constructing the ‘Genuine American City’: Neo-Traditionalism, New Urbanism and Neo-Liberalism in the Remaking of Downtown Milwaukee.” Cultural Geographies 11, no. 1 (2004): 73-98.

Latus, Mark A., and Mary Ellen Young. Downtown Milwaukee: Seven Walking Tours of Historic Buildings and Places. Milwaukee: Bicentennial Commission, 1978.

Olson, Frederick I. “When Downtown Meant Something.” Milwaukee History 23, no. 3 (2000): 56-68.

Ward, Kevin. “‘Creating a Personality for Downtown’: Business Improvement Districts in Milwaukee.” Urban Geography 28 no. 8 (2007): 781-808. doi: https://doi.org/10.2747/0272-3638.28.8.781.

Williams, Duncan E. “Foundation Conditions in Downtown Milwaukee.” PhD diss., University of Wisconsin, 1954.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.