Ever since citizens of the United States began to legally settle the area in the 1830s, Milwaukee has had to address, in an ever-increasingly organized manner, different types of crime. Some of these illegal actions have been perpetuated by individuals and others involved incidents of collective criminal behavior. Some of this crime has been against people and others against property. On one level, the motivations for these actions can appear similar in nature, but they often have complex backstories.

Crime in Early Milwaukee

Before Milwaukee was chartered as a city in 1846, a township constable and a village marshal ostensibly provided for the public safety. In reality, leading citizens such as Solomon Juneau often rallied residents as needed to address serious violations of the social order. For instance, the first murder in Milwaukee occurred in July of 1836. It involved two liquor dealers killing a customer, a Native American. After the citizenry apprehended the suspects and attempted to secure them in a makeshift jail, they escaped and fled the area. The following year, a committee of nine was appointed to arrest the unknown assailants of a “Mr. McNeil” and to bestow punishment upon them for the sake of the community’s “good order.”

On the heels of population growth that paralleled the city’s incorporation, Milwaukee experienced civic discord at a level that ultimately required a more formal approach. Volunteer, self-help responses were no longer sufficient, as evidenced when an angry crowd of Germans protested an 1849 law requiring saloonkeepers to be responsible for the public behavior of their customers. This protest led to considerable damage at the house of a local state senator who had favored this legislation. Shortly thereafter, in 1851, members of the volunteer fire department were appointed as special policemen to protect a “traveling lecturer” (a former priest) whose presence generated a violent protest that caused $150 in damages. Two years later, labor unrest among railroad workers led to vandalism and the mayor’s head being assaulted with a shovel when he intervened. Once again, the volunteer fire department had to intervene for the sake of public order. And the following year, 1854, Joshua Glover, a fugitive slave living and working in Racine, was captured and beaten. He was temporarily housed in the Milwaukee jail until upwards of 5,000 people assembled to protest this manifestation of America’s slave system at work in Southeastern Wisconsin. Elements within the crowd smashed the jailhouse door, using timbers from a nearby construction site (the Cathedral of St. John the Evangelist). This disorder allowed Glover to escape. He was taken to Waukesha briefly before fleeing to a more secure future in Canada.[1]

Crime at both the individual and collective levels was clearly growing sufficiently to warrant a more systematic response. Consequently, on October 4, 1855, the Milwaukee Police Department (MPD) was created with ten officers. These individuals were selected primarily for their size and ability to fight. Such a modest force, though, was not always adequate to resist periodic outbreaks of collective violence, such as occurred in Milwaukee’s lone lynching. In September 1861, two African Americans were accused of causing the death of an Irish resident from the Third Ward following a verbal exchange. A mob consisting of perhaps dozens, perhaps hundreds confronted the police chief and two of his officers, overwhelmed these policemen (including knocking down the chief with a slingshot). The rioters took one of the suspects (the other escaped) for the façade of a “street trial” before hanging him. And yet, over succeeding decades, Milwaukee was by and large thought to be an “orderly city.” This relative peace was aided by a slow, cost-conscious expansion of the city’s law enforcement team. The department in 1885 employed ninety-six employees. A “real jewel in the crown” of this department was added that year with construction of a new Central Police Station on Oneida Street (now East Wells Street) and North Broadway Street. Beyond liquor-related conflicts, Milwaukee appears to have remained a rather safe city in terms of violent crime amidst America’s exploding urbanization. In 1894, for instance, there was a single “cold-blooded” murder, along with seven deaths resulting from fights involving intoxicated offenders or victims.[2]

Twentieth Century Developments

During the 1900s, the City of Milwaukee dealt with crime in the same manner as many other cities in America. Crime and social disorder were addressed, in part, by the enforcement of vagrancy laws. The Milwaukee Police Department instituted a “Morals Squad” during the early and mid-1900s to enforce laws regarding what was vaguely referenced as the “moral order,” including gambling, prostitution, drunkenness, and unemployment, as well as what might be considered antisocial behavior. For example, using the vagrancy law, Milwaukee police could arrest and detain individuals who were mired in poverty or manifested other negative social characteristics, including spitting or tossing trash on the sidewalk or for being from the wrong nationality or race. Mainstream citizens believed such “miscreants” to be the most likely to be involved in criminal activity.

Milwaukee had a low crime rate from the late 1800s through the early 1900s. In 1906, Milwaukee recorded one homicide, while Chicago had twenty-two. Milwaukee had six reported burglaries in 1906 compared to Chicago’s 840. Safety in Milwaukee at the time is attributed to vigilant enforcement of laws against transient vagrants.[3] For decades, the City of Milwaukee enforced vagrancy laws to control social order and suppress crime. However, in 1972, the United States Supreme Court ruled in Papachristou v. City of Jacksonville that statutes on vagrancy were not permitted because of their vagueness. This violation of the due process clause of the Fifth Amendment to the Constitution ended the enforcement of most vagrancy laws across the country.[4] In place of vagrancy laws, Milwaukee and other cities turned to enforcing local ordinances and state statutes on “disorderly conduct.” The civil violation of disorderly conduct for the City of Milwaukee is classified under the “Morals and Welfare” section of the Milwaukee City ordinances, and declares: “Disorderly Conduct. 1. PROHIBITED. It shall be unlawful for any person to engage, in a public or private place, in violent, abusive, indecent, profane, boisterous, unreasonably loud, or otherwise disorderly conduct under circumstances in which such conduct tends to cause or provoke a disturbance.”[5] Many violations of the social order fall under the disorderly conduct ordinance. Law enforcement agencies in the region continue to use the disorderly conduct statute and ordinances to control lower level violations of the social order.

Since the early days of Milwaukee when homicides were relatively rare, violent crime and murder have increased over time. In recent history, the number of homicides in Milwaukee has fluctuated. In 1984, homicides in Milwaukee reached a historically recent low of forty-four (the U.S. Census Bureau listed the 1980 Milwaukee population as 636,212). Even as the population of Milwaukee experienced a slight decline to 628,088 in 1990, the number of homicides was gradually rising through 1991. This increase was reflective of a statistical uptick in violent crime and homicides across the nation during the last two decades of the twentieth century, a reality many attributed to a burgeoning illegal drug trade. These record numbers have been revisited in more recent years, with 146 homicides in the city in 2015 and 139 in 2016.[6] Yet between 2008 and 2014, there was only one year (2013) when there were more than one hundred homicides in the City of Milwaukee; between 2007 and 2013, violent crime dropped 11 percent, whereas property crimes decreased by 31 percent.[7] Clearly the quest for social order and civic peace that started in the pioneering days of Solomon Juneau when Milwaukee’s population numbered less than a hundred souls continues without end into a future where hope springs eternal for a safer, more tranquil world.

A Few High Profile Crime Episodes in the Milwaukee Area

Civil War Draft Riot

A searing example of just how fragile the public order was in early Milwaukee can be seen during the Civil War draft riot in Port Washington. Between June and August of 1862, President Lincoln authorized an additional 300,000 men for the Union army. From Wisconsin, he demanded nearly 12,000 men. By this time, many Wisconsinites as well as other Northerners were war-weary, and a draft was the only possible way to provide the manpower demanded by the military situation. The drawing of the names of able-bodied, adult men was to be done on November 10, 1862 in Port Washington. A crowd estimated at 1,000 assembled at the courthouse. The rioters destroyed the draft records, assaulted the draft commissioner, and threw him down the courthouse steps. A warehouse was looted, buildings were vandalized, and some onlookers were beaten. Wisconsin Governor Edward Salomon instructed eight companies of soldiers to restore order in Port Washington.[8]

Even though the presence of the soldiers dispersed the crowd, nearly 200 rioters were arrested. Prior to their trial, the prisoners were ceremoniously paraded in the City of Milwaukee. A draft was being held in Milwaukee the following week, and no one wanted a repeat of the riots in Port Washington. Troops were stationed on the roads leading into Milwaukee and in the courthouse where the draft was held. There were no reports of further disturbances.[9]

Theodore Roosevelt Assassination Attempt

The campaign for the presidency of the United States came to Milwaukee in 1912. The election was among Democrat Woodrow Wilson, Republican William H. Taft, Socialist Eugene V. Debs, and National Progressive Party (Bull Moose Party) candidate Theodore Roosevelt, who had previously served as president of the United States. By this time, however, Roosevelt had split from the Republican Party to run as the Progressive Party candidate for president.

On October 14, 1912, Theodore Roosevelt was to make several campaign appearances in Milwaukee. His schedule for the day included a parade and giving a speech at the Milwaukee Auditorium (now the Miller High Life Theatre). Even though he had not been feeling well, he insisted on keeping all of his commitments to the campaign in Milwaukee. Prior to the speech at the Milwaukee Auditorium, Roosevelt attended a banquet at the Hotel Gilpatrick on Third Street.

After dinner, Roosevelt walked outside to his awaiting car for the trip to the Milwaukee Auditorium. Just prior to entering his vehicle, Roosevelt stopped to tip his hat and acknowledge a cheering crowd that had gathered outside the hotel. A man in the front of the crowd pulled a pistol and shot at Roosevelt from point blank range. The bullet struck Roosevelt in the right side of his chest. As he collapsed into his vehicle, his stenographer, Elbert Martin, jumped on the assailant to prevent any further shots. Although the crowd wanted immediate and violent revenge, Roosevelt called for calm. Even though the bullet had entered Roosevelt’s chest, he insisted on going straight to the Milwaukee Auditorium to deliver his speech. At the Auditorium, Roosevelt took out his prepared speech that he had folded in two and tucked in his breast pocket of his overcoat. The pages of his lengthy speech deflected the bullet away from his heart to a non-fatal resting point on the fourth rib on his right side. Although the rib was fractured, he delivered his lengthy speech before he received medical treatment at Milwaukee Hospital.[10]

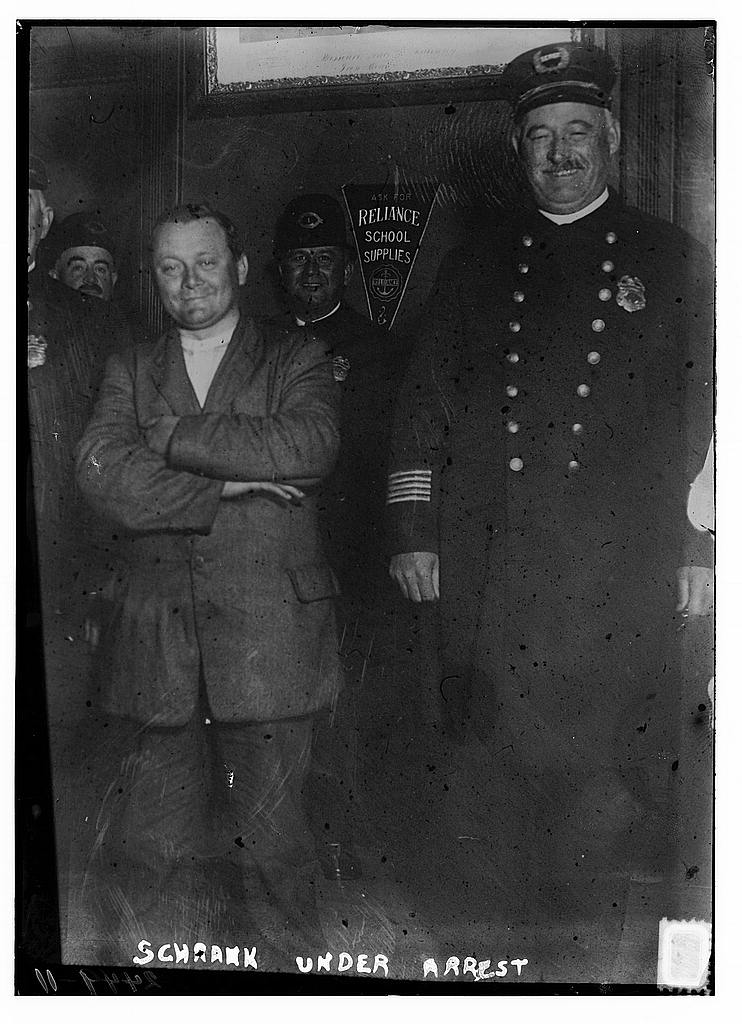

It was John Flammang Schrank, a thirty-six-year-old barkeeper from New York City, who shot the former president. Schrank suffered from mental health issues and had followed Roosevelt over several campaign stops before his assassination attempt in Milwaukee. In 1914, Schrank was placed in the Central State Mental Hospital, located in Waupun. He remained hospitalized at the State Mental Health Hospital until his death in 1943.[11]

Organized Crime and Bootlegging

Bootlegging in Milwaukee during the Prohibition era (1920-1933) differed from many other cities and regions. The history, culture, and a large part of the economy of Milwaukee were built on the brewery industry. The breweries, the brewery workers, and drinking establishments were bedrock institutions in the City of Milwaukee. In 1918, the year the national Prohibition amendment was enacted, there were 1,980 saloons in Milwaukee, one for every 230 residents.[12] Carrie Nation, the most well-known proponent of prohibition, lamented the culture of alcohol consumption in the city by stating: “If there is any place that is hell on earth, it is Milwaukee.”[13]

Public opinion in Milwaukee was strongly opposed to any legal restriction on an individual’s ability to consume alcohol. The Milwaukee Police Department prepared for the worst in their anticipation of enforcing prohibition laws. It was also the position of the prosecutor’s office in Milwaukee that any violence associated with the criminal activity of bootlegging “would be vigorously investigated and prosecuted.”[14] In practice, however, the Milwaukee Police Department enforced laws against alcohol consumption selectively. Police “sponge squads” made occasional visits to speakeasies to enforce liquor laws. Yet anyone who wanted to imbibe in Milwaukee could easily find a drink without much fear of arrest.[15]

In Milwaukee, notably, bootlegging went on without the volume of violence and homicides experienced in other large cities. The most notable crime during the Prohibition era in Milwaukee was the murder of an underworld figure, bootlegger Frank Aiello. He was related to Joe Aiello, an organized crime figure in Chicago and a rival of Al Capone.[16]

Organized Crime after Prohibition

Frank Balistrieri, a widely known organized crime figure in Milwaukee, attended Marquette University in Milwaukee in 1939 and 1941 but withdrew from the college both times and never completed his degree. By the 1950s, he had become involved in organized crime, skimming approximately $2 million in profits from casinos in Las Vegas that were owned by organized crime elements.[17] Balistrieri was also involved in controlling the highly profitable but illegal vending machine operations throughout the City of Milwaukee. The F.B.I. recorded his conversations during an investigation into his illegal activities. On these recordings, he indicated involvement in crimes ranging from murder to illegal gambling profits in Milwaukee and Kenosha.[18] During his tenure as a crime boss, Balistrieri was sentenced to several prison terms at both the federal and state level. In September 1985, Balistrieri was convicted on federal charges related to his involvement with the Las Vegas casinos.[19] He was released from federal prison on November 5, 1991 and died on February 7, 1993, of heart-related natural causes at the age of 74. He is buried in Holy Cross Cemetery.

The Lawrencia “Bambi” Bembenek case

Lawrencia “Bambi” Bembenek was hired as a Milwaukee police officer in March 1980, when she was 21 years old. Months later, in August, she was fired from the MPD during her probationary period. A friend of Bembenek’s had informed investigators that Bembenek smoked marijuana during the spring of 1980.[20]

That fall, Bembenek took a job as a waitress at the Playboy Club in Lake Geneva, Wisconsin. About the same time, she met and later began having an affair with Milwaukee police detective Elfred Schultz. That same month, Elfred Schultz divorced his wife, Christine. Elfred Schultz and Lawrencia Bembenek were later married in January of 1981.

In the early morning hours of May 28, 1981, Christine Schultz was murdered in the Milwaukee home she had shared with Elfred Schultz during their marriage. Christine Schultz was killed by a single .38 caliber pistol shot fired point-blank through her heart. She had been bound and gagged.[21]

Lawrencia Bembenek denied involvement in the murder but was arrested for the murder of Christine Schultz on June 24, 1981. The Milwaukee Police Department built a case based primarily on circumstantial evidence. At the time of Bembenek’s arrest, she was working as a Public Safety Officer at Marquette University in Milwaukee. She made her initial court appearance while still wearing her Marquette Public Safety Officer uniform.[22]

After a trial in 1982, Lawrencia Bembenek was sentenced to life in prison. She was serving her sentence at the Taycheedah Correctional Institution, located near Fond Du Lac, Wisconsin, when she escaped from the prison in July 1990 through a laundry room window. Captured three months later, she was found in the company of her fiancé (Dominic Gugliatto) in Thunder Bay, Ontario.[23] Media reports during her escape from prison gave Bembenek the label “Bambi,” and it stuck. This inspired the phrase, “Run, Bambi, Run,” which was used extensively to describe her flight from authorities. Bembenek was sent back to prison but was later released on parole in 1992. In the time that followed, Lawrencia Bembenek suffered severe emotional and physical problems that resulted in her requiring hospice care. She died in 2010 at the age of 52 in Portland, Oregon, from hepatitis C and kidney and liver failure.[24]

Serial Killer Jeffrey Dahmer

Jeffrey Dahmer was born in Milwaukee on May 21, 1960. When he was six years old, he moved with his family to Ohio, eventually settling in Bath Township in Ohio in 1968. During his teens, Dahmer experienced severe psychological issues and abused alcohol. He killed his first victim in 1978 when he was 18 years old. Dahmer picked up a seventeen year old hitchhiker named Steven M. Hicks. After drinking beer and having sex, Dahmer did not want Hicks to leave. Dahmer struck Hicks in the head with a barbell, making Hicks his first homicide victim.

Dahmer served in the U.S. Army from January 1979 until March 1981. He was discharged early due to his alcohol abuse and in 1982 moved West Allis to live with his grandmother on 57th Street. During the seven years he lived with his grandmother, Dahmer killed four more victims. Subsequently in May of 1990, Dahmer moved to the Oxford Apartments, located at 924 N. 25th St., Unit 213, in Milwaukee. The structure was a three-story brick apartment building with forty-nine small, one-bedroom apartments. Dahmer acknowledged that he frequented gay-oriented taverns in Milwaukee where he met many of his victims. On occasion, he approached juveniles who were outside such a bar and lured them to his apartment by promising them money to pose for or view gay pictures or videos. Once in the apartment, Dahmer drugged his victims with crushed sleeping pills and then strangled them.

On May 26, 1991, Dahmer met Konerak Sinthasomphone, a fourteen-year-old Laotian-American. Sinthasomphone agreed to pose for photographs in Dahmer’s apartment, where Dahmer drugged him. While Dahmer stepped out, Sinthasomphone was able to shake off the drugs and leave the apartment. Sinthasomphone was disoriented, bruised, and naked as he stumbled in the area of N. 25th Street and W. State Street. Glenda Cleveland and her eighteen year old daughter, Sandra Smith, observed Sinthasomphone and called the Milwaukee Police Department. Dahmer convinced the responding officers that the fourteen-year-old Sinthasomphone was staying at his apartment. Dahmer also told the officers that Sinthasomphone was nineteen years old, was drunk, and they had a misunderstanding. Officers returned Sinthasomphone to Dahmer. Glenda Cleveland called the Milwaukee Police Department later that night and spoke with one of the responding officers. She expressed concern that she believed it was a child that she observed incoherent and naked. The officer explained that it was his belief that Sinthasomphone was an adult; he informed her that no further action would be taken on the matter. Dahmer later confessed to killing Konerak Sinthasomphone that night after police left.

On July 22, 1991, thirty two year old Tracy Edwards escaped from Dahmer’s apartment after being drugged. Officers observed Edwards was near the Oxford Apartments with handcuffs secured on one of his wrists. Edwards led police to Dahmer’s apartment where they discovered evidence of multiple homicides. Milwaukee officers immediately placed Dahmer under arrest.[25] In total, Jeffrey Dahmer killed at least seventeen victims, one in Ohio and sixteen in the Milwaukee area. The majority of his victims were African Americans, many from the gay community. On February 15, 1992, a jury in Milwaukee determined that Dahmer was sane and responsible for his crimes. He was sentenced to fifteen consecutive life sentences. His sentence was to be served at the Columbia Correctional Institution in Portage, Wisconsin.

On November 28, 1994, as part of his duties while incarcerated, Jeffrey Dahmer was assigned to clean the gymnasium at the correctional institution. He worked with two other inmates, Jesse Anderson and Christopher Scarver. Anderson had been convicted of killing his wife by stabbing her multiple times (see below). Christopher Scarver was African American and was serving a life sentence for a homicide he committed in 1990. Scarver attacked both Dahmer and Anderson. Scarver used a twenty-inch metal bar to repeatedly strike the heads of his victims. Jesse Anderson and Jeffrey Dahmer both died as a result of the attack.[26] Christopher Scarver received two additional life sentences for the murders.

Jesse Anderson

Jesse Anderson was convicted of killing his thirty-three year old wife, Barbara, in the parking lot of Northridge Mall shopping center on April 21, 1992. Northridge Mall was located on N. 76th Street and Brown Deer Road, on the northwest side of Milwaukee. (The mall is no longer in operation after closing in 2003.)

Jesse Anderson was thirty four years of age when he murdered his wife by stabbing her more than twenty times. Anderson himself suffered four self-inflicted stab wounds. Three of the wounds were superficial, while the fourth punctured his lung. Jesse Anderson falsely informed officers that he and his wife were both attacked by two African American males.[27] Due to inconsistencies in his initial statement, the Milwaukee Police Department did not act on the false information. They built a strong case against Anderson that resulted in his arrest on April 29, 1992. After a trial by jury, Jesse Anderson was found guilty on August 13, 1992. He was sentenced to life in prison for the murder of his wife. As noted above, in November 1994 as part of his duties while incarcerated, Jesse Anderson was cleaning the gymnasium at the Columbia Correctional Institution located in Portage, Wisconsin. He was assigned to clean the area with Milwaukee serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer and a twenty-five yearold inmate named Christopher Scarver. Scarver attacked and killed both Anderson and Dahmer, receiving two additional life sentences for these latest crimes.[28]

Footnotes [+]

- ^ Bayrd Still, Milwaukee: The History of a City (Madison, WI: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1948), 102-03; John Gurda, The Making of Milwaukee (Milwaukee: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 1999), 50, 69, 94; John G. Gregory, History of Milwaukee, Wisconsin (Chicago, IL: S. J. Clarke Publishing Company, 1931), 2: 1122-23.

- ^ Maralyn A. Wellauer-Lenius, Milwaukee Police Department (Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing Company, 2008), 9-10; Still, Milwaukee, 232-33; Gregory, History of Milwaukee, Wisconsin 2: 1124-26.

- ^ Kevin Abing, A Crowded Hour: Milwaukee during the Great War, 1917-1918 (Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2017), 180; Still, Milwaukee, 357, 553.

- ^ Mitchell B. Chamlin and Steven G. Brandl, “A Quantitative Analysis of Vagrancy Arrests in Milwaukee, 1930-1972,” Journal of Crime and Justice, 23, no. 1 (1998): 23-40.

- ^ Milwaukee City Ordinance: Morals and Welfare, Section 106-1.

- ^ The Milwaukee Journal Sentinel runs a “Homicide Tracker” database containing information including age, cause of death, race, and gender of the victim, and whether an arrest has been made, from 2015 onward. See Milwaukee Homicides, Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, https://projects.jsonline.com/apps/Milwaukee-Homicide-Database/, last accessed June 8, 2018.

- ^ Ashley Lutheran, “Homicides Soar in Milwaukee,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, http://archive.jsonline.com/news/crime/homicides-soar-along-with-many-theories-on-cause-b99653861z1-366891381.html, accessed January 18, 2016; “Milwaukee Homicides: 2016,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.; George L. Kelling, Policing in Milwaukee (Milwaukee: Marquette University Press, 2015), 179; S. Abadin and M. O’Brien, “2016 Milwaukee Homicide Review Commission Annual Report,” Milwaukee Homicide Review Commission and City of Milwaukee Health Department (September 2017), 17.

- ^ Lawrence H. Larsen, “Draft Riot in Wisconsin, 1862,” Civil War History 7, no. 4 (December 1961): 421-427.

- ^ John W. Oliver, “Draft Riots in Wisconsin during the Civil War,” Wisconsin Magazine of History 2, no.3 (March 1919): 334-337; Susan T. Falch, “The Port Washington Civil War Draft Riot: National Implications of a Local Disturbance” (MA thesis, University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire, 2012), 43-45.

- ^ Doris Kearns Goodwin, The Bully Pulpit (New York, NY: Simon & Schuster, 2013), 732-733.

- ^ “Milestones: Sep. 27, 1943,” Time, September 27, 1943, http://content.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,850367,00.html, last accessed June 8, 2018.

- ^ “Milwaukee Timeline: Beer,” Milwaukee County Historical Society, accessed February 20, 2015, http://www.milwaukeehistory.net/education/milwaukee-timeline/.

- ^ Jennifer Herman, Wisconsin Encyclopedia, 2008-2009 Edition (Hamburg, MI: State History Publications, LLC, 2008), 146.

- ^ Ted Robert Gurr, Violence in America: The History of Crime (Newbury Park, CA: Sage, 1979), 154-156.

- ^ John Gurda, The Making of Milwaukee (Milwaukee: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 1999), 238-239.

- ^ Gavin Schmitt, Milwaukee Mafia (Charleston, S.C.: Arcadia Publishing: 2012), 23.

- ^ Federal Bureau of Investigation: Milwaukee Division, “A Brief History,” http://www.fbi.gov/milwaukee/about-us/history-1, Federal Bureau of Investigation website, accessed 2015.

- ^ “Crime Leaders as Cited by the F.B.I,” New York Times, August 6, 1978.

- ^ “Reputed Milwaukee Crime Figure Pleads Guilty in Kansas City Trial,” New York Times, January 1, 1986.

- ^ Kris Radish, Run, Bambi, Run (New York, NY: Carol Publishing Group, 1992), 26.

- ^ James Rowen, “The Night Christine Schultz Was Killed: A Fresh Look at the Bembenek Case,” Milwaukee Journal, January 13, 1991; Jo Sanin, “The Bembenak Highlights,” Milwaukee Journal, December 7, 1992, A6.

- ^ Lawrencia Bembenek, Woman on Trial (New York, NY: Harper Collins Publishing, 1992), 115-127.

- ^ Emma Brown, “Lawrencia ‘Bambi’ Bembenek, 52, Fugitive Captured Public Sympathy,” Washington Post, November 21, 2010.

- ^ Amy Rabideau Silvers, “Laurie Bembenek Dead at 52,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, November 21, 2010.

- ^ Anne E. Schwartz, The Man Who Could Not Kill Enough: The Secret Murders of Milwaukee’s Jeffrey Dahmer (New York, NY: Carol Publishing Group, 1992).

- ^ Rogers Worthington, “Inmate Charged in Dahmer Killing Says God Ordered It,” Chicago Tribune, December 16, 1994. See also Lionel Dahmer, A Father’s Story (New York, NY: Harper Collins Publishing, 1994) and Donald A. Davis, The Jeffrey Dahmer Story: An American Nightmare (New York, NY: St. Martin’s Paperbacks, 1991).

- ^ Rogers Worthington, “Once a Victim, Now a Suspect,” Chicago Tribune, April 28, 1992.

- ^ Rogers Worthington, “Inmate Charged in Dahmer Killing Says God Ordered It,” Chicago Tribune, December 16, 1994.

For Further Reading

Dahmer, Lionel. A Father’s Story. New York, NY: William Morrow and Company Inc., 1994.

Harring, Sidney. “The Police as a Class Question: Milwaukee Socialists and the Police, 1900-1955.” Science and Society 46 (2) (1982): 197-221.

Kelling, George L. Policing in Milwaukee: A Strategic History. Milwaukee: Marquette University Press, 2015.

Still, Bayrd. Milwaukee: The Story of a City. Madison, WI: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1948.

Tithecott, Richard. Of Men and Monsters: Jeffrey Dahmer and the Construction of the Serial Killer. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1997.

Wellauer-Lenius, Maralyn A. Milwaukee Police Department. Mount Pleasant, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2008.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.