As is the case with most matters of vice, gambling has a history in Milwaukee that dates back to the community’s foundations. The area’s earliest gambling dens catered to lead miners from across southeastern Wisconsin. These men, flush with cash and accustomed to a rugged lifestyle, made sure that the village’s earliest card games were honest. A crooked dealer was “liable to serve as a target for some inconsiderate opponent who preferred a shooting affray to losing against a sure thing,” according to an 1895 remembrance in the Milwaukee Journal.[1]

Faro, a card game with origins in France, was among the most popular games of chance in early Milwaukee. There was little popular outrage about the presence of the game or the tendency of respectable residents to wager money while playing. Among those who ran a regular game was Ninian Whiteside, who had been drawn to the area during the mining boom of the 1840s. Whiteside later used the connections he had made in the game to gain election to the 1846 state constitutional convention and later served the very first assembly speaker of the state assembly.[2]

By the 1870s, a game for the masses had reached Milwaukee in “policy.” The game was almost identical to the modern-day lottery, with players making a small bet on a small series of numbers. Bets could be placed at a number of saloons and stores where policy agents, who reported back to a central boss, were stationed. Twice per day, winning numbers were drawn in a national office in Kentucky and wired to the city. Frank Dalzell was the city’s policy king, running a game so profitable that he lived in a palatial mansion on Twenty-First Street and Grand Avenue. The game was mostly ignored by police until the early 1880s, when a state anti-policy law led to a crackdown that relegated it to the underground.[3]

Despite the regulations against policy, gambling in the city was largely ignored by the authorities until the 1890s, when city clergymen pressured police to take action. A major vice squad raid in 1892 shut down eleven gambling dens that had been offering poker, roulette, craps, and faro.[4] Many remained opened, however. In 1895, after making an undercover tour of illegal gaming rooms in the western half of downtown already known for its numerous brothels and dive bars, a group of Methodist ministers assailed the police and Mayor John Koch.[5] Although the mayor dismissed the uproar as an overreaction, the remaining dens lowered their public profiles.[6]

The popular movement against gambling continued into the 1900s, although Mayor David Rose, in office from 1898 to 1906 and again from 1908 to 1910, preferred to allow the dens to run as openly as they pleased. “As long as the people of Milwaukee continue to reelect Mayor Rose I suppose we shall have to put up with the gambling,” said one anti-gambling city alderman in 1905.[7] The 1910 election of the Socialist Emil Seidel, who ran on an anti-corruption platform, brought an end to the days of wide-open illegal gambling in the city.[8]

During the Roaring Twenties, even as illegal bars and speakeasy nightclubs flourished, city officials insisted that there was little illicit gambling to be found in Milwaukee, with much of the action having been pushed out beyond the county lines to resort towns and out-of-the-way roadhouses. Raids that did uncover gaming dens in the city found that card games and roulette were still popular, along with betting in sporting events and horse races.[9]

Policy returned to Milwaukee in the 1920s, the racket now controlled by shop owners and barkeepers in the city’s growing African American community. The game become a staple of Bronzeville’s local economy and, by the 1940s, police estimated that it was generating over $1 million annually. Winning numbers were originally drawn from a steel drum in neighborhood back rooms, but player complaints about crooked games led operators to innovate in how they chose their winnings combinations—including using the final digits of the daily newspaper circulation figures or the U.S. Treasury’s end-of-day balance. The game began to fade after Joe Harris, widely-acknowledged as black Milwaukee’s “king” of illegal gambling, died in 1960. Harris left behind a complicated legacy. While his business certainly preyed on the community, he was also one of its most generous benefactors.[10]

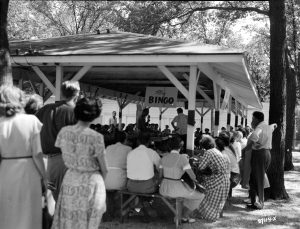

Into the 1960s, with the moral furor over gambling beginning to fade, changes to state laws first allowed for legalized forms of gambling in Milwaukee. With its prohibition of “lotteries” in the original 1839 Wisconsin territorial statutes, any form of gambling was technically against the law. In 1965, state voters first modified this prohibition, approving a constitutional amendment that allowed for residents to participate in sweepstakes and promotional contests. In 1973, charitable bingo games (a long-time staple for fundraising drives in spite of the law) were permitted; charitable raffles were legalized in 1977.[11]

Proposals to legalize lottery drawings in Wisconsin dated back as far as 1939 and reemerged periodically over the next several decades, with the proceeds from the proposed games designated for various charitable causes. The drive for a state-sponsored lottery floundered through the 1970s, but when the matter was finally put to a public vote in 1987, it was approved by a margin of nearly 2-to-1, with the profits from lottery designated for property tax relief. Scratch-off lottery tickets debuted in 1988 and a number-matching game—remarkably similar to the policy games that police had fought for decades—debuted in 1989.[12]

In 1991, a court ruling cleared the way for legalized Indian gaming in Wisconsin and the state entered into a gaming compact with the Forest County Potawatomi tribe to operate a casino in Milwaukee on land in the Menomonee Valley formerly occupied by the tribe. Major expansions to the casino in 2000, 2006, and 2008, and the addition of a 381-room hotel on the site in 2014 have since turned the casino, now known as Potawatomi Casino and Hotel, into the largest gaming facility in Wisconsin, attracting over 6 million guests annually.[13]

Footnotes [+]

- ^ “Early Day Gambling,” Milwaukee Journal, May 25, 1895, p. 1.

- ^ “Early Day Gambling,” Milwaukee Journal, May 25, 1895, p. 1; Milo Milton Quiafe, The Convention of 1846 (Madison, WI: Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 1919), .799.

- ^ “The Lottery Cases,” Milwaukee Daily News, July 22, 1879, p. 4; “Ruining Happy Homes,” Milwaukee Sentinel, December 11, 1882, p. 2; “Policy Parasites,” Milwaukee Sentinel, December 17, 1882, p. 7; “No Policy Played Here,” Milwaukee Sentinel, September 27, 1885, p. 3.

- ^ “Milwaukee Gambling Dens Closed,” Chicago Tribune, March 1, 1892, p. 6.

- ^ “Attack the Police,” Milwaukee Journal, May 6, 1895, p. 6.

- ^ “No Change in Policy,” Milwaukee Journal, May 6, 1895, p. 1; “Early Day Gambling.”

- ^ “Up to the Mayor,” Milwaukee Journal, January 21, 1905, p. 4.

- ^ Ann-Elise Henzl, “How Did Socialist Mayors Impact Milwaukee?,” WUWM website, posted August 12, 2016, accessed August 24, 2017.

- ^ “Big Gambling House Opens,” Milwaukee Journal, December 27, 1929, section 2, p. 1.

- ^ Matthew J. Prigge, “The Policy Kings of the Sixth Ward,” Shepherd Express, November 16, 2015.

- ^ “The Evolution of Legalized Gambling in Wisconsin,” State of Wisconsin Legislative Reference Bureau, Internal Bulletin 12-2, November 2012, accessed August 24, 2017.

- ^ “The Evolution of Legalized Gambling in Wisconsin,” State of Wisconsin Legislative Reference Bureau, Internal Bulletin 12-2, November 2012, accessed August 24, 2017.

- ^ “The Evolution of Legalized Gambling in Wisconsin,” State of Wisconsin Legislative Reference Bureau, Internal Bulletin 12-2, November 2012, accessed August 24, 2017; “Our History,” Potawatomi Casino website, Casino History Page, accessed August 24, 2017.

For Further Reading

“The Evolution of Legalized Gambling in Wisconsin.” State of Wisconsin Legislative Reference Bureau, Internal Bulletin 12-2, November 2012.

Prigge, Matthew J. “The Policy Kings of the Sixth Ward,” Shepherd Express, November 16, 2015.

Prigge, Matthew J. Milwaukee Mayhem: Murder and Mystery in the Cream City’s First Century, Madison, WI: Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 2015.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.