Milwaukee’s history is layered into its residents’ everyday lives. They commute to work on streets named for long-gone pioneer roads—Watertown Plank Road, to name one—or noted places or people, like National Avenue, named for the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers (the old home for Civil War soldiers established in 1867 that looms over the West Side). They pass landmarks named for Milwaukeeans of the distant past: Whitnall Park, after the father of Milwaukee County’s famous park system; Milwaukee Mitchell International Airport, named after the scion of a powerful nineteenth-century political and commercial family who also lent their names to Mitchell Park and its Domes; Marquette University, named after one of the first European explorers to come ashore from the Milwaukee River in 1674 near the park also named after him. They drop off their children at schools named after prominent Milwaukeeans, Americans, and world leaders, from Civil War general Rufus King to the politician Robert La Follette, from the poet William Cullen Bryant to the writer Hamlin Garland, and from the scientist Luther Burbank to the Israeli leader (and former resident of Milwaukee) Golda Meir. And they seek out entertainment at venues with names from the city’s commercial and political past, including the Pabst Theater, Miller Park, and the Henry Maier Festival Grounds.

These are superficial, if omnipresent, examples of historical memory. But Milwaukeeans, like all communities, remember their history—or histories—in many ways. Indeed, the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee is an exercise in remembrance in that it aims to provide a basic introduction to virtually every aspect of the four-county area’s history.

Yet “memory” is not exactly history; it is, rather, the way in which a community chooses to remember—or chooses not to remember. Memory provides a narrative that may or may not mesh with reality. That narrative can be sweeping, focusing on certain elements of a place’s past—Milwaukee’s status in the early twentieth century as the “most foreign” city in America, for instance, or its long-gone leadership in manufacturing and brewing—or microscopic—focusing on individuals or institutions that brought fame or infamy on themselves and their city.

A place remembers its past in many ways and for many reasons:

- to promote an image of itself for commercial purposes

- to commemorate events that distill salient aspects of that history

- to provide an identity for a city or for communities within that city

- to whitewash or to redeem past wrongs

- to identify notable people whose fame might rub off

Although hardly an exhaustive list, at least three threads wind through the ways in which Milwaukeeans “remember” their past: the hardships and successes of the founding generations of Milwaukee; its extraordinary commercial and industrial might from the late nineteenth through the mid-twentieth centuries; and the ethnic (and more recently, racial) diversity that characterizes its population.

Chronicling the Past, Organizing Memory

Published histories of Milwaukee have followed a pattern familiar to residents of most American cities, with a mix of chronicles of pioneer fortitude, admiring biographies of powerful men, humorous anecdotes describing accepted community stereotypes, and a sprinkling of works by professional historians. Throughout this Encyclopedia, after each entry, there are suggestions for further reading. The lists include countless books and articles, on specific parts of the histories of the city and of the four counties.[1]

But the creation of a set of shared memories is generally left to authors and historians who try to offer a coherent, long view of the community. The first “history” of Milwaukee, published less than twenty years after the city was formally established, drew on interviews with the pioneers who settled it. It focused on the rapid growth of the town from Indian outpost to bustling young city full of finely dressed women and modern stores. Thus, as occurred in virtually every city that emerged on the ever-moving American frontier, the legend of early hardships overcome by ambitious and often quarrelling men was established as one of the threads of memory that would never really fade away.[2] James S. Buck’s Pioneer History of Milwaukee: From 1840 to 1846, Inclusive, took two volumes to cover in extraordinary detail the city’s pre-settlement history and its first six years; not surprisingly, it was formally approved, with a frontispiece “Certificate,” by the Old Settlers’ Club and the Pioneer Club that “certified to the lifelike truthfulness of the reminiscal sketches of the pioneers.”[3]

Gilded Age authors tended to emphasis Milwaukee’s growing economic might, largely through histories of the development of transportation, industry, banking, and the press, and biographies of prominent entrepreneurs and businessmen. Howard Louis Conard’s two-volume, 1000-page History of Milwaukee County from Its First Settlement to the Year 1895 helped form the second thread of Milwaukee memory by chronicling the extraordinary contributions made by the county and region to the nation’s economy, with a few chapters showing how that economic power had also developed the city’s artistic and cultural institutions.[4]

William George Bruce, a publisher and activist on behalf of the development of the city’s educational system and its harbor, produced another massive history in 1922. Although it provided a general history of the city, the original volumes and their several supplements also focused on the great men who Bruce believed had made Gilded Age and Progressive Era Milwaukee great.[5]

Written by city native and long-term newspaperman John G. Gregory a decade after Bruce’s tome, the History of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, reads more like a history than the earlier booster histories. Yet it also focused on pioneer development and industrial magnificence and included chapters covering most facets of the city’s economic and social institutions, from building roads and railroads to individual industries, from hotels and the waterfront to public health and education, and from churches and schools to the press. Gregory added, however, the third thread of memory—Milwaukee’s proud heritage of immigration from Europe. And through it all, the city’s history was presented—in a style typical of the pre-Cold War era—as a series of progressive triumphs.[6]

A couple of popular histories of the city, both written by newspapermen, appeared after the Second World War. H. Russell Austin’s The Milwaukee Story: The Making of an American City, was produced by the Milwaukee Journal to commemorate the city’s centennial (and first appeared serially in the Journal’s “Green Sheet”). It aimed to be a “popular, yet complete and authentic narrative of the city’s life, from prehistoric times to the present” in a little over two hundred pages. It focused on colorful characters, from Solomon Juneau to the powerful Mitchell family and the infamous madam Kitty Williams, as well as on famous fires, the Bridge War, and other “stirring episodes” from the city’s past.[7] Yet another journalist, Robert W. Wells, produced a similar, although more purposefully “lighthearted,” to use his own term, anecdote-filled history in 1970. Along the way, he managed to articulate one of those self-effacing stereotypes that provide another thread of memory when he suggested that a “true Milwaukeean” would never actually buy this book, but “would read it over someone’s shoulder.”[8] Wells declared, “Any history is an arbitrary selection of what the historian hopes are facts,” and commented, “This is a more arbitrarily selected smorgasbord than most, leaving out the things I found dull.” He explained that, “I’m not a historian and this book does not attempt to be a scholarly evaluation.”[9]

But Milwaukee has not been without its actual historians, and although they have not neglected the threads that have linked many generations of Milwaukee memory, they have taken more critical looks at the origins and development of those memories. The most important comprehensive histories appeared fifty years apart. Bayrd Still’s Milwaukee: The History of a City, provided a thoroughly professional yet optimistic look at Milwaukee’s history as successful example of rapid urban development. Still had received his PhD at the University of Wisconsin and was a long-time member of the history department at New York University, so he had no close ties to the city; he was not, for a change, a local booster or newspaperman.[10]

John Gurda’s 1999 The Making of Milwaukee provided the most complete picture of Milwaukee’s past. Without neglecting its pioneer heritage, its industrial heyday, or its immigrant heritage, Gurda also detailed the collapse of that industrial economy and the complications and inequities of race relations since the 1960s. In 2006, Gurda’s book was also made into a five-hour documentary. It won a regional Emmy award and is still shown on the local public television station.[11] Two important anthologies have also provided more nuanced takes on Milwaukee institutions and politics by professional historians: Ralph M. Aderman, Trading Post to Metropolis: Milwaukee County’s First 150 Years and Margo Anderson and Victor Greene, eds., Perspectives on Milwaukee’s Past.[12]

Milwaukee’s Place in History and Culture

The first level of memory honors not only local founders and pioneers, but also Milwaukee’s place in important national and international events. A few examples of art offer somewhat whimsical glimpses of the city’s past. The statue of Gertie the Duck and her ducklings recreates the famous story of the family of ducks hatched near the Wisconsin Avenue bridge in the Downtown during the waning days of World War Two. The “Bronze Fonz” commemorates one of the most beloved fictional Milwaukeeans, Arthur “The Fonz” Fonzarelli, one of the characters on Happy Days, the 1970s sitcom that helped ensconce Milwaukee in a nostalgic haze for the 1950s and 1960s.[13]

But most sculptural manifestations of Milwaukee history are more serious. A number of statues and busts honor local pioneers, international literary and musical giants (Robert Burns, for instance, and the several German writers and composers who decorate a plaza near the bandshell in Washington Park); national heroes, including George Washington (dominating the “Court of Honor” near the downtown public library), of course, and Abraham Lincoln (looming over Lincoln Memorial Drive next to the War Memorial), as well as the trio of foreigners who fought on the Patriot side in the American Revolution (Tadeusz Kosciuskzo, Baron von Steuben, and Casimir Pulaski); local figures like Solomon Juneau, Patrick Cudahy, Christian Wahl, and Douglas MacArthur, and explorers like Leif Ericson and Pere Jacques Marquette. None, however, honors a specific woman (although a Cathedral Square statue portrays “Immigrant Mother.”)[14]

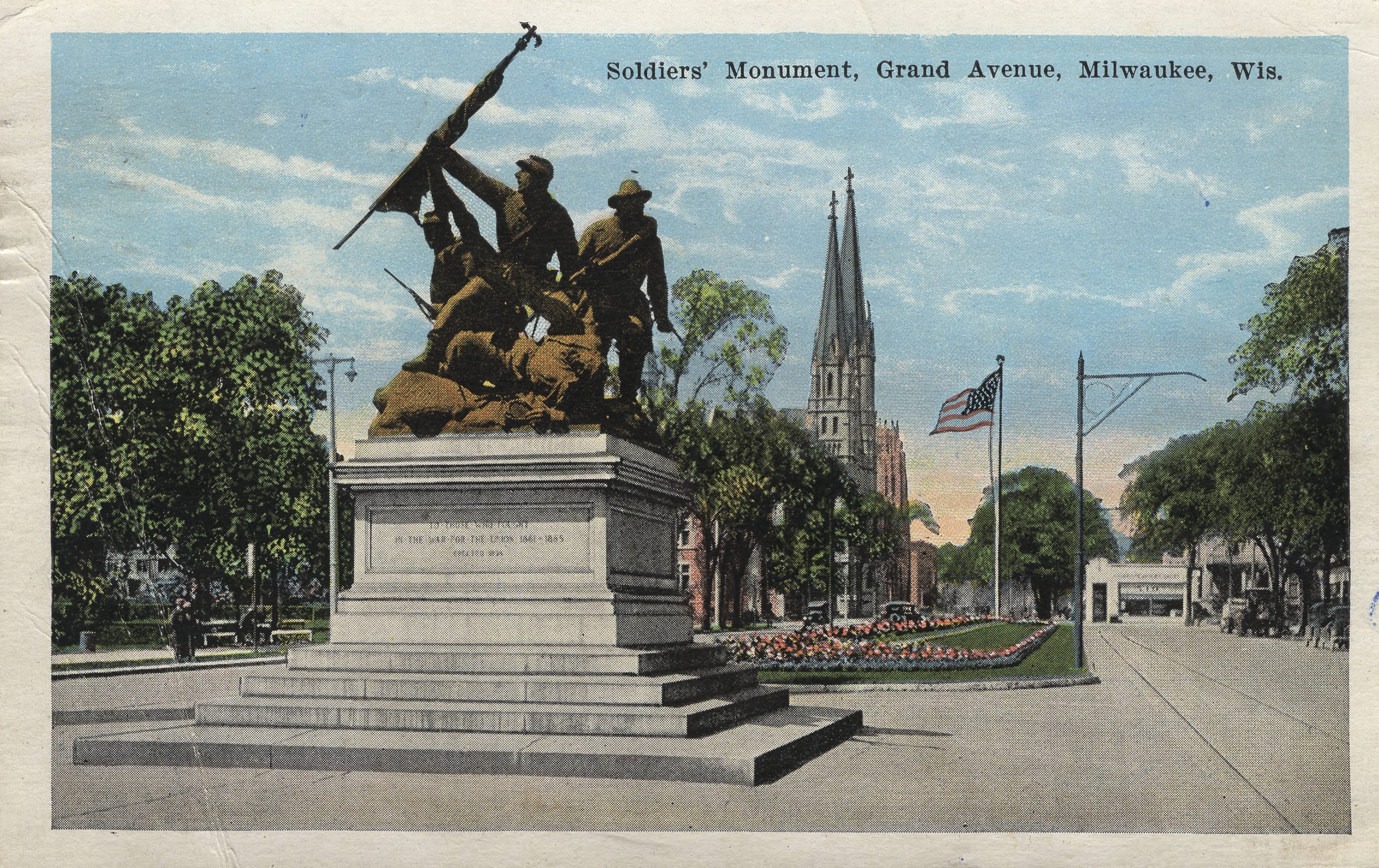

Although Milwaukee was, of course, far from the fighting, several statues and markers commemorate the city’s role in the Civil War, from the location of training camps (including Camp Sigel on the East Side) to the Soldiers and Sailors monument towering over Wood National Cemetery at the old National Home grounds, to “The Victorious Charge” on Wisconsin Avenue near the west end of downtown. In addition to the aforementioned statue of Lincoln at the far east end of the Avenue, a small stone marker with a brass plate on the Marquette University campus commemorates the soon-to-be president’s speech at the Wisconsin State Fair in 1859.

The overwhelming majority of Milwaukee County landmarks note existing or former houses, schools, clubs, cultural institutions, cemeteries, and other human-made structures. Although there are far fewer landmarks and markers in Waukesha, Ozaukee, and Washington Counties, a similar pattern emerges. That’s neither surprising nor unusual; buildings are easy to interpret. Although rarely contextualized in the city’s larger history, these historic structures or markers describing vanished historic structures can easily represent iconic themes in the city’s history, and, indeed, often inspire very public as well as sentimental efforts at historic preservation—with mixed results. For instance, the failed 1980 effort to prevent the destruction by Marquette University of the Plankinton Mansion led the Common Council to strengthen the city’s historic preservation laws.[15]

Since the 1970s, the city’s leading advocacy group for historic preservation, the non-profit Historic Milwaukee, Inc., has offered neighborhood tours that focus on historic architecture and on neighborhoods undergoing renewal or preservation—Walker’s Point, for instance, and Concordia.[16]

Industry and Labor

A poster produced in the 1980s by the Department of City Development immortalized an illustration from The Book of Milwaukee: Development, Resources, Enterprise and Beauty of the Peerless Cream City (Milwaukee: Evening Wisconsin Company, 1901), an illustrated album of Milwaukee manufacturing and commercial firms. Declaring that “Milwaukee Feeds and Supplies the World,” the busy illustration featured a giant globe with Milwaukee shining like a north star, a busy port, an idealized white woman holding symbols of brewing and industry, and locomotives steaming out to the hinterland, no doubt packed with processed foods, industrial products, and beer. This is the historic memory of Milwaukee that prevailed for much of the city’s history and still is represented in some ways.[17]

This notion of Milwaukee’s commercial engagement with the world has echoed through the decades, long after the factories and breweries and tanneries celebrated in the album vanished or were converted into offices or condos. Working men and women are celebrated in a few places, including the collection of paintings and sculptures of men at work featured at the Grohmann museum at the Milwaukee School of Engineering (although few of those feature Milwaukee or even Wisconsin). The chain link fence that surrounds Zeidler Union Square downtown (a Milwaukee County park on Michigan Avenue) boasts labor-friendly phrases and slogans such as “Equal Pay for Equal Work” and “Workers of the World Unite.” The “Statue of Labor” in Jackson Park commemorates workers, as does Omri Amrany’s “Teamwork,” erected to honor the memory of the three iron workers killed by the collapse of the “Big Blue” crane during the building of Miller Park.[18]

But it’s far easier to find examples of historical memory focusing on the industrialists and financiers for whom these unnamed workers labored. Indeed, the careful preservation of such architectural gems as the Central Library (built in 1895 and designed by Milwaukee’s architects to the stars, Ferry and Clas), City Hall (another 1895 structure with a Flemish Renaissance design that was the tallest structure in the city until the 1970s), and the Mitchell Building (an 1876 building with gaudy Gilded Age architecture) reflects a pride in Milwaukee’s long-ago prominence as one of the engines of America’s economic power.

It’s no coincidence that one of the newest and most popular museums in the region is the Harley-Davidson Museum, which commemorates the ingenuity and hard work that went into building the iconic vehicles and the iconic business. The museum and the old headquarters on Highland Avenue draw thousands of pilgrims a year; they remind the city not only of its industrial past and present, but also of its somewhat tangential connection to a certain bad-boy element of American pop culture.

The Harley museum provides access to one of the newest major additions to the Oak Leaf bike trail, the Hank Aaron Trail. It is named for one of the city’s—and nation’s—greatest baseball players (it passes close by the new Miller Park and the site of old County Stadium, where Aaron played for many years). But the eastern third or so of the trail meanders through the Menomonee River Valley, where interpretive panels explain the Valley’s industrial, polluted past, and celebrate the newer generation of light industries that have redeemed the Valley.[19]

Race and Ethnicity

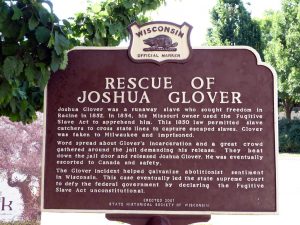

The fraught history of race in Milwaukee is well-known to journalists and activists, but it barely registers in the city’s historical memory. Significant portions of Bronzeville, the old African American neighborhood north and west of downtown, were bulldozed in favor of freeway construction. But the most prominent examples of race in Milwaukee memory are the celebratory historic marker in Cathedral Square and the mural painted under one of those freeways describing and depicting, respectively, the “rescue” of a free black man named Joshua Glover from slave catchers in 1854. Caroline Quarlls, another escaped slave who made her way to freedom through Milwaukee, is represented across the street from Glover.[20]

Aside from a somewhat muddled memory of the origins in Ojibwe of the name “Milwaukee,” the native presence Milwaukee is largely relegated to a few historic markers and the giant casino and hotel that loom over the Menomonee Valley, with a rooftop “flame” and various artistic references to the region’s native past. Virtually all of the countless burial and effigy mounds made by natives before European contact were destroyed; markers note surviving mounds in Lake Park and State Fair Park, and more than two dozen mounds are protected in Lizard Mound County Park in West Bend.[21] The Potawatomi Business Development Corporation took over a number of historic buildings in the old Concordia University campus on the near west side of Milwaukee, restoring several of them and giving them names based on Potawatomi words such as Bgemagen (War Club), Nengos (Star), and Wgetthta (Warrior).[22]

In some ways, Milwaukee’s historical societies and institutions are as segregated as its population. The Milwaukee County Historical Society archives and interprets all of Milwaukee’s history but tends to focus on the longer and somewhat better documented history of European settlers and their descendants. It is complemented by the Wisconsin Black Historical Society and the America’s Black Holocaust Museum, not to mention the Jewish Museum Milwaukee. The city’s well-loved ethnic festivals, most of which do at least nod toward providing snapshots of their community’s histories, also ensure that they are remembered separately from the other racial and ethnic groups who have lived in the city.

Perhaps nothing summarizes more accurately the separate memories of Milwaukee than the renaming of Third Street in 1984. When the African American community successfully lobbied to have it renamed Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Drive, business owners along the cobblestone blocks stretching north from Wisconsin Avenue—blocks that are lined with bars and restaurants, including the iconic Mader’s German restaurant and, just a bit north and across the street, Usinger’s sausage factory—managed to get the southern part named “Old World Third Street.”[23]

The African American presence in the formal representations of historical memory has increased somewhat in recent years, as several public and charter schools have been named for local politicians and activists like Lloyd Barbee. In spring 2018, a long stretch of 4th street—from downtown all the way north to Capitol Drive—was named after the recently-deceased politician, judge, and civil rights activist Vel Phillips.[24]

Branding

In the 1980s, Milwaukee’s Department of City Development launched one of the most ambitious efforts to provide a unified historical memory of Milwaukee as a city of neighborhoods through a series of posters funded by a block grant from the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development. Each featured a striking image representing some facet of the neighborhood’s architectural history or a noted landmark. Jan Kotowicz created the original images; local historian John Gurda wrote a two-to-three thousand word history and description of each neighborhood that was printed on the posters’ reverse sides. The posters subtly evoked many of the contours of the city’s collective memory. Jackson Park’s poster featured a quartet of rowboats and geese, representing the somewhat worse for wear ponds that still dot the county’s famous parks, while the Rufus King neighborhood poster features an art deco version of the grand old high school. Historic churches and other buildings represent some neighborhoods, including Gesu on Marquette University’s campus and St. Sava Serbian Orthodox Cathedral on the South Side. The Wisconsin Avenue bridge illustrates Miller Valley, while the iconic water tower represents North Point and an old movie palace, the Oriental Theater, represents the East Side. Other posters feature architectural details characteristic of the housing stock from certain neighborhoods: a classic stained-glass window from a Milwaukee bungalow illustrates Washington Heights; an old campus building illustrates Concordia neighborhood; stone houses represent Story Hill. Kotowicz added a dozen posters in 2015 (but also changed the names of several neighborhoods and dropped several others). The new images were published in conjunction with Gurda’s richly illustrated Milwaukee: City of Neighborhoods, a much-expanded and updated version of his poster-sized neighborhood histories. Kotowicz used city hall to represent Downtown, a warehouse conversion for the Historic Third Ward, the Lake Park lighthouse for the Upper East Side, and the eponymous band shell for Washington Park.[25]

Elements of the city’s industrial past appear in the posters through the celebration of buildings erected in Milwaukee’s heyday—the old Milwaukee Gas Light plant in the Menomonee Valley, for instance—and hints of the city’s ethnic past also survive, especially in the illustrations of some of the neighborhood churches that began as centers of ethnic communities. Having said that, race is barely represented in posters (it plays a much more central role in Gurda’s book)—not in Sherman Park, North Milwaukee, Merrill Park, or any of the predominantly black neighborhoods. And none of the posters portray the fast-growing Hispanic or Asian communities.

Participants in the annual Doors Open Milwaukee, organized by Historic Milwaukee, Inc., get a little better feel for the diversity of the city and some of the suburbs. During this two-day autumn event, experts, enthusiasts, and caretakers offer free tours—some more in-depth tours are offered for a fee—of over 170 buildings, institutions, organizations, and galleries. The sites range from civic buildings like fire stations to historic churches, from old breweries turned into commercial enterprises and old businesses turned into craft breweries, and neighborhood hangouts and iconic corners. Many are rooted in neighborhood histories and customs, and some include newer communities, including African American, Hispanic, and South Asian sites.[26]

While artful and entertaining, the branding of Milwaukee in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, while continuing to honor an important and inherently interesting history of one of middle America’s most important cities, did not move the historical memory of Milwaukee much past the parameters established a century earlier.

Footnotes [+]

- ^ For a more comprehensive list of writing about Milwaukee, see Ann M. Graf, Amanda I. Seligman, and Margo Anderson, Bibliography of Metropolitan Milwaukee (Milwaukee: Marquette University Press, 2014).

- ^ A. C. Wheeler, The Chronicles of Milwaukee: Being a Narrative History of the Town from its Earliest Period to the Present (Milwaukee: Jermain & Brightman, 1861).

- ^ James S. Buck, Pioneer History of Milwaukee: From 1840 to 1846, Inclusive (Milwaukee: Symes, Swain & Co., 1877, 1881).

- ^ Howard Louis Conard, ed., History of Milwaukee County from Its First Settlement to the Year 1895, 2 vols. (Chicago, IL: American Biographical Publishing Co., 1895).

- ^ William George Bruce, ed., History of Milwaukee, City and County, 4 vols. (Chicago, IL: S. J. Clarke Publishing Co., 1922).

- ^ John G. Gregory, History of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, 2 vols. (Chicago, IL: S. J. Clark Publishing Co., 1931).

- ^ H. Russell Austin, The Milwaukee Story: The Making of an American City (Milwaukee: Milwaukee Journal, 1946), quote on p 9.

- ^ Robert W. Wells, This is Milwaukee (Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Co, 1970), vii.

- ^ Wells, This is Milwaukee, vii.

- ^ Bayrd Still, Milwaukee: The History of a City (Madison, WI: Wisconsin State Historical Society Press, 1948).

- ^ John Gurda, The Making of Milwaukee (Milwaukee: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 1999); “Gurda’s Making of Milwaukee Rebooted for 10th Anniversary,” Milwaukee Independent, July 19, 2016, accessed August 8, 2018.

- ^ Ralph M. Aderman, Trading Post to Metropolis: Milwaukee County’s First 150 Years (Milwaukee: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 1987), and Margo Anderson and Victor Greene, eds., Perspectives on Milwaukee’s Past (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2009).

- ^ Chris Foran, “When Milwaukee Met Gertie the Duck,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, April 25, 2017, accessed August 8, 2018; “Bronze Fonz,” Visit Milwaukee, accessed August 8, 2018.

- ^ “Milwaukee County Landmarks,” Milwaukee County Historical Society, accessed August 4, 2018.

- ^ Chris Foran, “When They Tore Down a Mansion and Rebuilt the Push to Save Milwaukee’s Past,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, October 10, 2017, accessed January 3, 2019.

- ^ “About Us,” Historic Milwaukee Inc., accessed August 8, 2018.

- ^ “The Mystery of Milwaukee Feeds and Supplies the World,” Milwaukee Public Museum, accessed May 3, 2018.

- ^ Zeidler Union Square Photographs from author’s collection; “Jackson Park,” Urban Milwaukee, accessed August 5, 2018; Susan Shemanske, “Miller Park Workers Receive Permanent Honors,” Journal Times, August 25, 2001, accessed August 5, 2018.

- ^ “Informational Signs,” Friends of the Hank Aaron Trail, accessed August 5, 2018.

- ^ Christian Schneider, “Hey, Hollywood: How about These Stories,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, March 7, 2014, accessed August 5, 2018.

- ^ Marie Kohler, “Indian Mounds: Wisconsin’s Priceless Archeological Treasures,” Shepherd Express, June 15, 2011, accessed January 3, 2019.

- ^ Tom Daykin, “Former Concordia Campus Will Be Converted for Urban Culture,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, July 23, 2016.

- ^ Carl Baehr, Milwaukee Streets: The Stories behind Their Names (Milwaukee: Cream City Press, 1995), 141-142, 197.

- ^ “Find a School,” Milwaukee Public Schools, accessed August 4, 2018; Mary Spicuzza, “City Honors Vel Phillips with 4th St. Renaming,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, May 9, 2018.

- ^ John Gurda, Milwaukee: City of Neighborhoods (Milwaukee: Historic Milwaukee, Inc., 2015); Evan Solochek, “The Illustrated City,” Milwaukee Magazine August 26, 2010, last accessed April 14, 2019.

- ^ “Buildings,” Doors Open, accessed August 8, 2018.

For Further Reading

Aderman, Ralph M. Trading Post to Metropolis: Milwaukee County’s First 150 Years. Milwaukee: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 1987.

Anderson Margo, and Victor Greene, eds. Perspectives on Milwaukee’s Past. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2009.

Arcadia Publishing has produced scores of richly illustrated paperback “histories” of Milwaukee neighborhoods, industries, churches, institutions, and ethnic groups. Their narratives are limited to detailed captions, but they are often useful sources of information for the threads of Milwaukee history explored in this essay. For a list of Milwaukee-related titles, go to: https://www.arcadiapublishing.com/Search?searchtext=milwaukee&searchmode=anyword&searchoption=allbooks, accessed August 8, 2018

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.