Milwaukee’s uniquely jagged borders and large size relative to most Midwestern cities are historical byproducts of its dramatic and often controversial territorial growth. Throughout the city’s history, Milwaukee has grown through two primary means: annexation, which expands a city’s boundaries through the gradual addition of adjacent territory, and consolidation, in which entire municipalities fully merge with the city. Milwaukee’s territorial expansion occurred during four main phases: first during the city’s early years between 1846 and 1893, when state laws governed municipal growth; then between 1893 and 1920, when territorial growth was tied to service extension; then between 1920 and 1932, when the Daniel W. Hoan administration made territorial growth a key policy; and finally between 1945 and 1960, when the Frank Zeidler administration also privileged territorial growth. It was not until the twentieth century that Milwaukee added a considerable amount of new territory, almost quadrupling in size from 25 square miles in 1920 to its present 96 square miles. This pattern of growth distinguishes Milwaukee from most northern industrial cities, where territorial additions usually slowed or ceased well before World War Two.

First Phases of Annexation

Milwaukee’s original 1846 borders traced Lake Michigan to the east, present-day North Avenue to its north, present-day Twenty-Seventh Street to its west, and present-day Greenfield Avenue to the south. Growth came slowly during Milwaukee’s first two phases of annexation. During the first phase, from incorporation in 1846 to 1893, the state legislature governed the addition of new territory to Milwaukee. A Wisconsin Supreme Court ruling in 1893 permitted cities to annex territory without state interference, but only at the request of property owners. The Wisconsin state legislature passed a new law in 1898 that initiated the city’s second phase of annexation, allowing a majority of property owners in a given area to petition a city to annex it. The new legal procedure proved cumbersome and effectively slowed the city’s physical growth just when its population exploded due to immigration and industrialization.[1] Milwaukee’s initially slow physical growth resulted from the city’s handling of public infrastructure. The greatest incentive for residents to support annexation came with the promise of connecting to the city’s water and sewer system. Between 1900 and 1910, however, Milwaukee sold water service to outlying communities without requiring annexation or consolidation.[2] As a result, from 1893 to 1920, Milwaukee virtually doubled its population, but new annexations added only 5.2 square miles to the city. By 1920, Milwaukee’s 457,147 residents squeezed onto 25.3 square miles of land, making Milwaukee the second most densely populated large city in the United States.

A third phase of annexation that saw Milwaukee gain a considerably greater amount of new territory began when the Social Democratic Party (Socialists) swept into the mayor’s office in 1910 and won 21 of 35 Common Council Seats. Alarmed by the city’s increasingly overcrowded conditions, Socialists placed a more aggressive approach to annexation on their party platform and also sought to make infrastructure provisions to non-city residents contingent upon agreeing to annexation. Emil Seidel, the first Socialist mayor, struggled to implement the new policies and was defeated in the 1912 election. However, a second Socialist, Daniel Hoan, won the mayoral election in 1916 and made annexation a key part of his policies during his twenty-four years in office. In 1922, the Milwaukee Common Council passed a new ordinance making all future extensions of the city’s water system contingent upon annexation to the city. When the 1920 U.S. Census results confirmed Milwaukee’s overcrowded conditions, Hoan and the Milwaukee Common Council responded by creating the Department of Abstracting and Annexation in 1924. At that time, state law required the Common Council to vote on each annexation petition, and for the rest of the 1920s, Council members supported the vast majority of new annexation petitions. The City of Milwaukee grew from its 25.3 square miles in 1920 to 44 square miles by 1932; the majority of that new growth came from annexation of territory in unincorporated towns such as Lake to the south, Wauwatosa to the west, the Town of Milwaukee to the north, and the Town of Granville to the northwest. The largest single addition of new territory, however, came in 1929, when residents of the Village of North Milwaukee voted to consolidate with the City of Milwaukee. Between 1919 and 1932, the city also heavily invested public money in annexed territories, laying 296 miles of water mains at a cost of $13 million and 393 miles of sewer lines at a cost of $14 million between 1919 and 1932.[3]

Deeply influenced by the Garden City planning movement and committed to German-style zoning, Milwaukee Socialists viewed annexation as a means to achieve well-planned, decentralized communities where residents would live in high quality homes closer to nature.[4] Socialist planning initiatives clearly depended upon the success of annexations in order to access new land for residences and businesses. The Garden Homes project, the first municipally-funded, cooperative housing community in the United States, was located on land outside city borders to the north, and several contentious annexations were required to make the community part of the city. The city also frequently linked annexations to other Socialist initiatives such as Charles Whitnall’s countywide system of parkways. Private interest groups largely supported the city’s annexation campaign for reasons of their own. The City Club of Milwaukee advocated annexation to alleviate overcrowding and to take advantage of open space outside the central city. If the city grew outward and continued to increase its population, the City Club believed, it could become one of the world’s great commercial and industrial cities. Real estate developers, now eager to connect their new subdivisions to city water and sewer lines, also became advocates of annexation during the 1920s.

The process of annexation also garnered opposition, especially from suburban residents and industrial corporations that had located many factories on land just outside city borders in order to avoid municipal restrictions. In the early 1920s, such industrial concerns included the A.O. Smith Corporation, whose largest plant was alongside the Chicago, Milwaukee, and St. Paul Railroad (Milwaukee Road) railway corridor to the northwest; Miller Brewing Company, Pawling & Harnischfeger, and the Falk Corporation, all of which had large plants located at the west end of the Menomonee River Valley, just past the city borders; and Nash Motors and Nordberg Manufacturing, located just south and west of city. Hoan failed to convince most of these corporations to submit to annexation, so Milwaukee officials frequently drew up annexation petitions that included irregular borders with acquiescent landowners that “captured” some of these industries. Such plans frequently became the target of lawsuits, such as an unsuccessful 1924 annexation attempt near Green Bay Road (in present day Glendale) that included a large factory owned by Nordberg Manufacturing.[5]

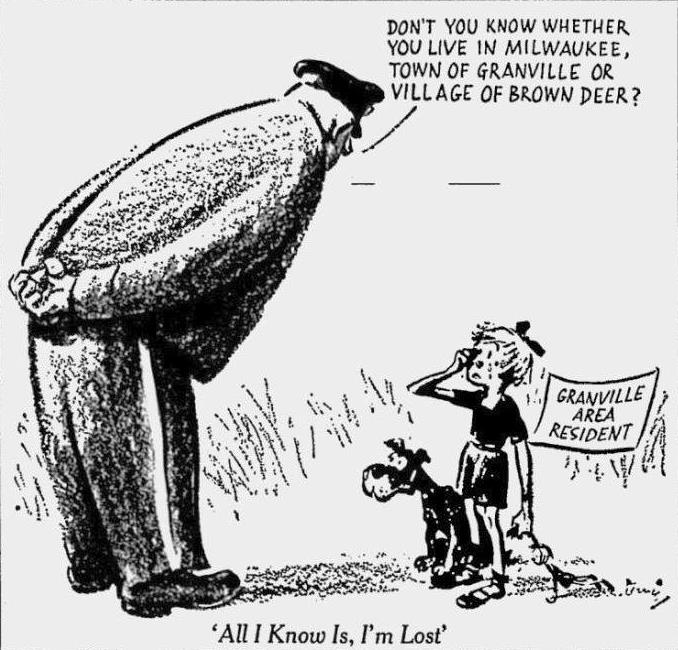

Unincorporated suburban communities resented losing land to every Milwaukee annexation. Attorneys representing the suburbs gave legal expression to such opponents who were informally referred to as the “Iron Ring,” a nickname that soon became collective vernacular for all of Milwaukee’s suburbs.[6] Incorporated suburban villages and cities could join the city only through municipal consolidation (not annexation); residents in most such places, such as Shorewood and Whitefish Bay, vociferously resisted consolidation with Milwaukee. Shorewood’s officials were so alarmed by Milwaukee’s growth that in 1921 its official bulletin instructed residents to notify local police if they heard of any annexation petitions being floated by Milwaukee near its borders. The city did successfully convince residents of the debt-stricken, working class village of North Milwaukee to consolidate in 1929. Unincorporated jurisdictions (referred to in Wisconsin as “towns”) were more directly threatened by annexation. In 1926, residents of the Town of Lake, which bordered Milwaukee to the south, and the Town of Milwaukee, which bordered the city to the north, organized referenda to incorporate their communities as “cities” to make annexation legally impossible. City officials, frightened by the prospect of Milwaukee’s growth grinding to halt, blitzed both communities with warnings of higher taxes and poor public services. Referenda in both townships failed by wide margins in the fall of 1926.[7]

Milwaukee’s relative success at annexation in the 1920s ended with the onset of the Great Depression, when fiscal concerns forced Mayor Hoan to curtail the program and dissolve the city’s Department of Abstracting and Annexation in 1932. Consequently, between 1932 and 1948, the city took in only 3.5 additional square miles of land. Attention turned to consolidating the city and county into a single government. A 1934 election-day advisory referendum asked all county voters of their interest in a complete city-county consolidation. The results revealed a clear city-suburban split. In total, 104,708 Milwaukee County residents voted in favor of consolidation, with only 40,319 opposed. However, of the seventeen suburban towns, villages, and cities in the county, only three—Milwaukee, West Allis, and Cudahy—had majorities of residents that voted in favor of consolidation. Alarmed that their city’s residents had voted in favor of consolidation, West Allis officials resubmitted the referendum to their residents, changing the question to read: “Do you believe that the City of West Allis should by consolidation (annexation) join the city of Milwaukee and thus become a ward or part of a ward of the City of Milwaukee?” With consolidation now presented as another arm of the larger city’s annexation efforts, West Allis residents overwhelmingly voted against the second referendum.[8]

Fourth Phase of Annexation

In 1946 the fourth phase of annexations commenced when housing concerns motivated the Milwaukee Common Council to re-establish the Department of Annexation and Abstracting. Arthur Werba, who had served as annexation director during most of Milwaukee’s expansion in the 1920’s, again headed up the re-born department. Real estate developers in the Milwaukee area again largely supported annexation in concept. Frank Zeidler, the city’s third and final Socialist mayor, won the 1948 election and gave annexation a broader civic purpose during his three terms as mayor. City officials, fearing a decline in property tax revenues, hoped annexation would bring in new industrial land.[9]

Zeidler and other Milwaukee officials revived the Hoan administration’s practice of using annexation to enable ambitious planning ideas to take root but encountered greater suburban resistance in the late 1940s and 1950s. One failed initiative included an attempt by the City of Milwaukee to help an organization of WWII veterans fund the purchase of the New Deal era Greenbelt village of Greendale, southwest of the city. City officials concentrated annexation efforts on linking Milwaukee to Greendale, assuming Greendale residents would vote to consolidate with Milwaukee if the purchase was successful. Residents of Greendale, however, opposed both the purchase of their village and any potential consolidation with Milwaukee. The village’s newspaper compared annexation to “colonization” and voted in a slate of village trustees who prevented the sale of Greendale to the city-backed veterans’ group.[10]

Annexation also underpinned a larger planning scheme begun in 1946 with the annexation of a five-mile long and 330-foot wide strip of land along Hampton Avenue to access the Chicago and North Western Railroad yards at the border of Milwaukee and Waukesha counties. The “Butler Strip” annexation, as the Hampton Avenue parcel became known (because it reached the Village of Butler to the west), gave Milwaukee access to Waukesha County. City officials quickly began making plans to build an enormous ten square mile “satellite community” of potentially 50,000 to 75,000 new residents on land attached to the Butler Strip annexation that the city would purchase and annex itself. However, part of the land along Hampton was in the Town of Wauwatosa, an old opponent of Milwaukee annexation. As the state Supreme Court listened to oral arguments in the Town of Wauwatosa vs. Milwaukee, nine local attorneys representing nine different suburbs in Milwaukee County filed briefs on behalf of Wauwatosa. Waukesha County residents who lived in the unincorporated towns of Brookfield and Menomonee, both in the path of Milwaukee’s proposed “satellite” community, formed a “Property Owners Association” with over 200 members to register opposition to the city’s plan. Additionally, the village board of Butler and the town board of Menomonee, both in the path of the annexation, maneuvered to oppose Milwaukee’s efforts. On April 3, 1951, the state Supreme Court ruled the Butler Strip annexation to be invalid.[11]

To comply with the court’s reinterpretation of annexation law, the Wisconsin state legislature passed and Governor Walter Kohler signed a new law in July of 1951 that required any incorporated municipality that sought annexation to post “notices of intent to annex” in at least eight public places within the towns where the proposed territory was located. Additionally, at least ten days before annexation petitions could be circulated, municipalities had to publish posting notices in a local newspaper. In Milwaukee County, the new law almost instantly set off a race to post notices of intent to annex. Suburban communities now increasingly sought to post their own annexation notices, to gain land of their own and to prevent annexation from Milwaukee. The new law also encouraged defenders of mass transit to try to link annexation to Milwaukee. In September 1951, five individuals announced that they had posted notices of intent for the city of Milwaukee to annex a thirty-eight square mile stretch of territory in the towns of Greenfield, Wauwatosa, and Franklin in Milwaukee County, and the towns of New Berlin and Brookfield in Waukesha County. The proposed annexation was conditional on the City of Milwaukee agreeing to purchase and operate the Milwaukee-Waukesha interurban line, formerly owned by the Milwaukee Rapid Transit and Speedrail Company, which had recently announced the abandonment of all operations just before its assets were liquidated. Milwaukee officials did not pursue the rapid transit annexation and instead became preoccupied with opposing a dizzying array of annexation attempts throughout Milwaukee County’s suburbs.[12]

Defensive Suburban Incorporation

The new annexation law encouraged residents to defensively incorporate their communities to block Milwaukee and protect tax revenues. Glendale incorporated as a city in 1950, breaking away from the Town of Milwaukee and blocking Milwaukee’s growth to its north. In 1951, residents in a portion of the Town of Lake, south of Milwaukee, incorporated the Village of St. Francis to prevent the city from annexing the Lakeside Power Plant. In early 1952, residents of a northern portion of the shrinking Town of Milwaukee (which dissolved entirely in the 1950s) incorporated as the Village of Bayside. At the same time, residents of the unincorporated community of Hales Corners, located on territory posted for annexation to Milwaukee, voted to incorporate as a village in January of 1952. Brookfield incorporated in 1954.

Suburban opposition to annexation after World War Two reached a crescendo in 1955, when residents of the largely rural Town of Oak Creek, which bordered Milwaukee to the south, successfully lobbied the Wisconsin State legislature to pass the “Oak Creek Law,” allowing unincorporated communities bordering Milwaukee to incorporate as “Cities” even if they lacked the four hundred persons per square mile population density that existing state law required. Oak Creek (1955) and Franklin (1956) incorporated under the provisions of the new Oak Creek law, and Greenfield (1957), Mequon (1957), and New Berlin (1959) incorporated as cities under different provisions of the Wisconsin law. As a result, Milwaukee’s annexation efforts slowed dramatically in the late 1950s. The city’s last two major land additions came from consolidation with unincorporated portions of the Town of Lake (in 1953) and the Town of Granville (made official by a state court decision in 1962). State officials created a “Metropolitan Study Commission” in 1956 to examine the possibility of consolidating some or all government functions among Milwaukee County municipalities, but little interest was registered, and the commission ended with no major recommendations for consolidation. The City of Wauwatosa, which first incorporated in 1897, annexed 8.5 square-miles of additional land in 1953 and attracted commercial concerns such as Mayfair Mall in 1958, and several new manufacturing facilities, including Harley-Davidson, Stroh Die Casting, and Briggs and Stratton.[13]

Not all annexations and consolidations have occurred in reaction to the city of Milwaukee’s growth. Other municipalities in southeast Wisconsin have also added new territory through annexation, including the cities of Waukesha and Pewaukee in Waukesha County, Port Washington and Cedarburg in Ozaukee County, and West Bend in Washington County. None of these suburban communities are adjacent to the City of Milwaukee. Annexation continued in some of these cities, such as Waukesha, throughout the twentieth century.

Milwaukee’s annexation battles created several distinct local patterns. Annexations and consolidations in the 1950s added more than fifty square miles to the city and provided Milwaukee with a remarkably large volume of open land within city borders for low-density industrial and residential development. The city’s municipal borders are notoriously jagged, especially where Milwaukee is adjacent with Greenfield. Blocks occasionally feature homes across the street from one another but in two separate municipalities. The city’s annexation history also indirectly created “rural cities” that defensively incorporated in the wake of the Oak Creek Law. The original city of Oak Creek contained agriculturally-zoned land in 80% of its territory. The City of Franklin’s original population density in the late 1950s was four persons per acre. The City of Mequon originally housed 8,543 residents on more land than the entire city of San Francisco.[14] No major land acquisitions have been made by Milwaukee since the late 1950s. In the early twenty-first century, no unincorporated towns remained in Milwaukee County.

Footnotes [+]

- ^ Entry originally posted April 3, 2019; entry revised December 22, 2020. Arnold Fleischmann, “The Politics of Annexation and Urban Development: A Clash of Two Paradigms” (Ph.D. diss., University of Texas at Austin, 1984), 88-92.

- ^ Kate Foss-Mollan, Hard Water: Politics and Water Supply in Milwaukee, 1870-1995 (West Lafayette, IN: Purdue University Press, 2001), 63-66.

- ^ John M. McCarthy, Making Milwaukee Mightier: Planning and the Politics of Growth, 1910-1960 (DeKalb, IL: Northern Illinois University Press, 2009), 64-67.

- ^ McCarthy, Making Milwaukee Mightier, 19-25.

- ^ Arthur Werba, “Annexation Activities of the City of Milwaukee,” 1927, Folder 1, Box 9, City Club of Milwaukee Records, 1909-1975, Milwaukee Area Research Center, Golda Meir Library, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee (hereafter MARC, GML).

- ^ Anthony Orum, City Building in America (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1995), 79-80.

- ^ “Lake Gives Up City Ambitions,” Milwaukee Sentinel, September 20, 1926; “Fight Attempt to Create City,” Milwaukee Journal, October 13, 1926.

- ^ Referendum Results, City of Milwaukee, November 6, 1934, Folder 3, Box 9, City Club of Milwaukee Records, 1909-1975, Milwaukee Manuscript Collection AS and Milwaukee Micro Collection 69, MARC, GML; see also Henry J. Schmandt and William H. Standing, The Milwaukee Metropolitan Study Commission (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1965), 57-58.

- ^ “Renews Policy on Annexation,” Milwaukee Journal, May 12, 1946, Annexation Clipping File, Milwaukee Public Library (hereafter MPL); Report of the Commission on the Economic Study of Milwaukee, 1948, 107, MPL.

- ^ Arnold Alanen and Joseph Eden, Main Street Ready Made: The New Deal Community of Greendale (Madison, WI: The State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1987), 79-88.

- ^ McCarthy Making Milwaukee Mightier, 151-163.

- ^ “Plan Annexing to Aid Transit,” Milwaukee Journal, September 15, 1951.

- ^ On West Allis’s annexations, see “Posting Clash in Greenfield Opens Battle,” Milwaukee Journal, October 2, 1951, Annexation Clipping File, MPL. For Hales Corners, see “H.C. Votes For Incorporation,” The Tri-Town News, January 31, 1952. For Wauwatosa and Butler, see “Two More Links in the Iron Ring,” Milwaukee Journal, March 14, 1952, Annexation Clipping File, MPL. For Bayside, see “Hearing on Bayside Set” Milwaukee Journal, April 6, 1952, Annexation Clipping File, MPL. For Wauwatosa, see 1957 Official Bulletin of the City of Wauwatosa, Folder 1, Box 2, Wauwatosa Collection, Milwaukee County Historical Society.

- ^ Land Use and Zoning Committee, MSC, “Proposed Findings and Conclusions Concerning Zoning in Milwaukee County,” Folder 5, Box 6, Zeidler Papers, MPL; Letter, Zeidler to Lamping, July 12, 1957, Folder 9, Box 56, Zeidler Papers, MPL.

For Further Reading

Goff, Charles. “The Politics of Governmental Integration in Metropolitan Milwaukee.” Ph.D. diss., Northwestern University, 1952.

Fleischmann, Arnold. “The Politics of Annexation and Urban Development: A Clash of Two Paradigms.” Ph.D. diss., University of Texas at Austin, 1984.

McCarthy, John M. Making Milwaukee Mightier: Planning and the Politics of Growth, 1910-1960. DeKalb, IL: Northern Illinois University Press, 2009.

Rast, Joel. “Annexation Policy in Milwaukee: An Historical Institutionalist Approach.” Polity 39 (2007): 55-78.

Please consider a few corrections to improve the accuracy of this informative entry.

Chapter 500, “Oak Creek Law” (1955)

The Towns of Oak Creek (1955) and Franklin (1956) used it to incorporate as fourth class cities since they bordered Milwaukee, a first class city (150,000 or more people).

Checking the incorporation certificates filed with the Wisconsin Secretary of State at the Municipal Data System, Historical Municipal Records From the Office of the Secretary of State, mds.wi.gov, the following above-mentioned towns could not and did not use the Oak Creek Law to incorporate as fourth class cities for the following reasons.

• Brookfield incorporated in 1954, one year before the Oak Creek Law passed in 1955.

• New Berlin and Milwaukee never bordered each other.

• Greenfield incorporated in 1957 as a third class city.

• When Mequon incorporated in 1957, it temporarily did not border Milwaukee. On July 10th, 1956, Circuit Judge Harvey Neelen voided 16.5 square miles of the contested April 3rd, 1956 Milwaukee-Granville 22.5 square-mile consolidation. He ruled Brown Deer’s various March 1956 annexations of 16.5 square miles of the Town of Granville took precedent, including the Corrigan tract (March 5th, 1956 10.5 square miles: W. County Line Rd., N. 68th St., W. Good Hope Rd. and N. 124th). The Corrigan annexation bordering Mequon became temporarily part of Brown Deer until Circuit Judge William O’Neill struck down Brown Deer’s Brown Deer Park, Corrigan and Laun annexations, but upheld its Johnson and Tripoli Club annexations on May 27th, 1959. The Corrigan tract reverted back to Milwaukee two years after Mequon incorporated. The Wisconsin Supreme Court upheld the Milwaukee-Granville consolidation and voided Brown Deer’s Brown Deer Park, Corrigan, Johnson and Laun annexations, but upheld the village’s Tripoli Club annexation on April 3rd, 1962, six years to the day when Milwaukee and Granville residents voted to consolidate in referendums.

• Additional Sources: The Milwaukee Journal, July 10th, 1956 and May 27th, 1959.

Mayfair Shopping Center

I remember when Mayfair was an open-air shopping center. It opened in 1958, not 1957, and was enclosed in 1973, six years after Brookfield Square opened as Milwaukee’s first indoor shopping center.

• Sources: The Milwaukee Journal, October 9th, 1958, October 25th, 1967 and October 5th, 1973.