As the city developed, Milwaukeeans razed, transformed, and replaced outmoded buildings, infrastructure, and other elements of the landscape. Some groups expressed concern that these changes destroyed history and a “sense of place.” They worked to mark, preserve, restore, and repurpose historically significant sites and structures.

Milwaukee’s first historic preservation efforts emerged in the late-nineteenth century. Fearing that the bourgeoning city was forgetting its frontier roots, a group of pioneers formed the Old Settlers’ Club in 1869 “with the object of preserving the associations, the memories, and the traditions of old Milwaukee.”[1] The club collected historic books, images, and artifacts, and marked historically important sites.[2]

Historic structures survived because of owners’ maintenance and repairs. The city typically intervened only to clear dilapidated buildings or those standing in the way of new development.[3] In a few instances, owners saved early Milwaukee buildings by moving them to new locations.[4] In 1938, the Works Progress Administration moved the Benjamin Church House from its old Kilbourntown neighborhood to Estabrook Park to serve as a museum.[5]

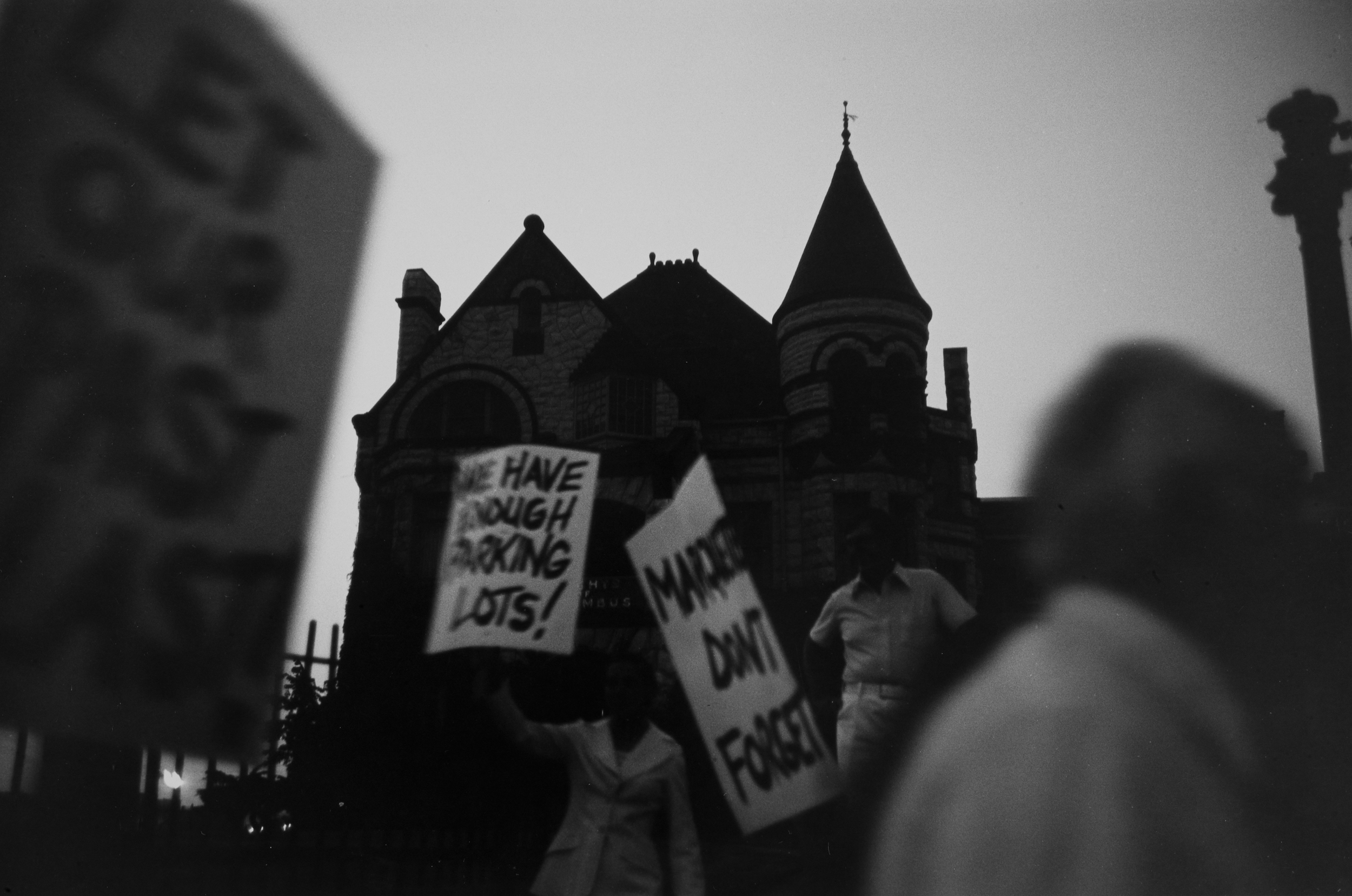

As Milwaukee sought to modernize after World War II, urban planners targeted large sections of the city for redevelopment. New preservation organizations formed to protect historically significant homes, churches, theaters, and other structures from demolition for new housing, freeways, and other urban renewal projects. The non-profit group, Land Ethics, Inc., for instance, organized in in the mid-1960s to save the Chicago & North Western depot on the downtown lakefront from clearance for a proposed Lake Freeway.[6] Although the depot was ultimately demolished in 1968, the battle was pivotal. It generated greater public interest and civic support for historic preservation.

Preservationists took advantage of new federal, state, and local preservation programs in the late twentieth century. Local groups succeeded in placing numerous Milwaukee-area sites on the National Register of Historic Places.[7] Local municipalities increased protection and financing for historic sites between the 1960s and 1980s. They established landmarks and preservation commissions, as well as Tax Incremental Financing districts and other funding programs.[8] Local groups received grants from the National Trust for Historic Preservation, state and county historical societies, and private foundations.

By the 1970s, preservationist activity encompassed whole districts. Individuals and businesses purchased and restored old houses and commercial buildings in aging neighborhoods. Groups like Historic Walker’s Point, Inc. (now Historic Milwaukee, Inc.) and the Sherman Park Community Association publicized preservation resources and pursued preservation as a neighborhood revitalization strategy.[9]

By the 1980s Milwaukee’s redevelopment plans increasingly included “the renovation, rehabilitation, and adaptive reuse of existing historic buildings.”[10] City officials collaborated with developers and business interests to turn the Third Ward’s old warehouses and factories into an upscale historic district of condominiums, art galleries, offices, and retail spaces.[11] Opened in 1982, the Shops at Grand Avenue incorporated several historic downtown commercial buildings, including the old Plankinton Arcade, Gimbels, and Boston Store, into a modern indoor shopping mall.[12] Since the 1980s, developers have also turned several of the old complexes of Milwaukee’s former brewing and tanning giants into new condominiums, artist studios, education facilities, and retail, entertainment, and office spaces.[13]

Several non-profit organizations still work to protect historic sites against deterioration, demolition, and redevelopment. The Milwaukee Preservation Alliance, for instance, has been especially concerned about the National Soldiers Home, which has deteriorated significantly with age.[14] Historic Milwaukee, Inc. also contributes to preservation efforts through tours and events that raise awareness and understanding about the city’s historic sites.[15]

Footnotes [+]

- ^ Old Settlers’ Club of Milwaukee, Early Milwaukee: Papers from the Archives of the Old Settlers’ Club of Milwaukee County (Milwaukee: The Club, 1916), 4-5; John Gurda, The Making of Milwaukee (Milwaukee: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 1999), 143.

- ^ Old Settlers’ Club of Milwaukee, Early Milwaukee, 6-7; Gurda, Making of Milwaukee, 143.

- ^ John M. McCarthy, Making Milwaukee Mightier: Planning and the Politics of Growth, 1910-1960 (DeKalb, IL: Northern Illinois University Press, 2009), 87-89, 103-104.

- ^ Frank D. Alioto, Milwaukee’s Brady Street Neighborhood (Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2008), 49.

- ^ H. Russell Zimmermann, The Heritage Guidebook: Landmarks and Historical Sites in Southeastern Wisconsin: Historically and/or Architecturally Significant Buildings, Monuments, and Sites in Five Southeastern Wisconsin Counties (Milwaukee: Heritage Banks, Inland Heritage Corporation, 1976), 96; “Kilbourntown House,” Milwaukee County Historical Society website, accessed April 14, 2015.

- ^ Cory Michael Grassell, “Milwaukee’s Historic Third Ward: Historic Preservation and Revitalization, 1976-2006” (Master’s thesis, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2007), 19.

- ^ Brian McCormick, “Factory Chic: Reusing Wisconsin’s Historic Industrial Buildings,” Wisconsin Magazine of History 85, no. 3 (Spring 2002): 47; Grassell, “Historic Third Ward,” 28.

- ^ Grassell, “Historic Third Ward,” 18, 27-28, 61-69.

- ^ Gurda, Making of Milwaukee, 393.

- ^ Trkla, Pettigrew, Allen & Payne, Nagle, Hartray & Associates, and Metro-Economics, Historic Third Ward: Urban Design and Development Potentials Study (Milwaukee: City of Milwaukee, Department of City Development, 1986), 23.

- ^ Grassell, “Historic Third Ward,” 59-112; Trkla, Pettigrew, Allen & Payne, Nagle, Hartray & Associates, and Metro-Economics, Historic Third Ward; McCormick, “Factory Chic,” 47-48.

- ^ Gurda, Making of Milwaukee, 408-409.

- ^ Thomas Collins, “$15 Million Plan Set for Schlitz Site,” Milwaukee Sentinel, May 7, 1985, sec. 1; “About the Brewery,” The Brewery: A Joseph J. Zilber Historic Redevelopment, http://www.thebrewerymke.com/about/index.htm, accessed July 15, 2014, information now available at http://www.thebrewerymke.com/about.html, last accessed August 7, 2017; Fran Bauer, “Blatz Building May Be Rebuilt,” Milwaukee Journal, May 7, 1985, sec. 2; EPA Brownfields and Land Revitalization Program, Pfister & Vogel Tannery: Transforming Milwaukee’s Largest Brownfield into a Sustainable Benefit for the Community (Washington, DC: United States Environmental Protection Agency, July 2010); Interim Historic Designation Study Report: Herman Zohrlaut Leather Company, Pfister & Vogel Tanning Company Complex (Milwaukee: City of Milwaukee, Department of City Development, November 2001); “The Tannery,” accessed November 20, 2014.

- ^ “Save the Soldiers Home,” Milwaukee Preservation Alliance, accessed May 8, 2015, information now available at http://www.milwaukeepreservationalliance.org/save-the-soldiers-home.html, last accessed August 7, 2017.

- ^ “About Us,” Historic Milwaukee, Inc. website, accessed May 8, 2015.

For Further Reading

Grassell, Cory Michael. “Milwaukee’s Historic Third Ward: Historic Preservation and Revitalization, 1976-2006.” Master’s thesis, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2007.

Knippel, Joyce Lynne. “Redefining Progress: A History of Historic Preservation in Milwaukee, 1964-1984.” Master’s thesis, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 1984.

McCormick, Brian. “Factory Chic: Reusing Wisconsin’s Historic Industrial Buildings.” Wisconsin Magazine of History 85, no. 3 (Spring 2002): 42-55.

Old Settlers’ Club of Milwaukee. Early Milwaukee: Papers from the Archives of the Old Settlers’ Club of Milwaukee County. Milwaukee: The Club, 1916.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.