Milwaukee’s emergence as a prominent American city coincided with the advent of modern popular culture in the late nineteenth century. As the city achieved national visibility, its popular identity shifted in ways that reflected historical developments, the demographics of the city, and evolving notions of the American Dream. Throughout most of its history, however, Milwaukee maintained the cultural image of a place of opportunity for the common person, and an urban community on a human scale that prided itself on its geniality and good cheer, which might always be enhanced by the beverage that became its defining commodity.

The earliest images of Milwaukee in popular culture emerged in popular literature and music, which became an increasingly big business in the Gilded Age. Few authors exerted more influence on American popular thought in the late nineteenth century than Horatio Alger, Jr. Alger’s novels embodied the ideal of individual upward mobility, celebrating the capacity of street children to transform their lives through his formula of “pluck and luck.” In Julius the Street Boy (Or Life in the West), Alger’s troubled young protagonist is sent to Wisconsin by a charitable agency to build his character in the open air of the West. Julius meets a businessman from Milwaukee en route, who describes the emerging city as a flourishing outpost of opportunity, and henceforth the main character hopes to one day find employment there.[1]

Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist Edna Ferber, herself a Wisconsin native, was a reporter for the Milwaukee Journal before authoring her first novel, Dawn O’Hara (1911). Ferber’s main character in that novel also works as a journalist in Milwaukee after leaving New York City, where her abusive husband is institutionalized because of his alcoholism. Like Alger, Ferber portrayed Milwaukee as a place to make a new start—this time for a woman in the Progressive Era—and as a healthier, more humane alternative to New York City.[2]

Barnstorming banjoist Charlie Poole and his North Carolina Ramblers, whom historians consider one of the seminal artists in the history of country music, recorded and popularized a song entitled “Milwaukee Blues” at the outset of the Great Depression. In Poole’s lyrics, the city served as a symbolic beacon for the rootless poor of the South: “I left Atlanta ’bout the break of day, the brakeman said, you’ll have to pay, got no money so I pawned my shoes, I want to go west, I got the Milwaukee blues.” While Poole died just a year after recording it, the song would be rediscovered during the folk revival of the 1960s and beyond, becoming a standard in American roots music.[3]

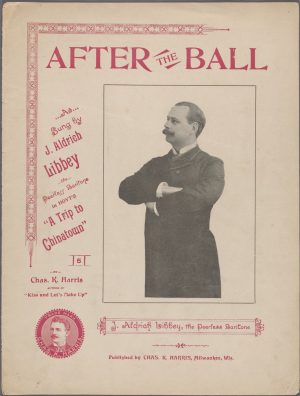

Perhaps the most significant Milwaukeean in the history of American popular culture was composer Charles K. Harris. Harris became the best-selling songwriter of the Tin Pan Alley era of the 1890s. While Milwaukee was never featured in the lyrics of his often maudlin songs (earning him the moniker “King of the Tear Jerkers”), Harris’s personal story is reflective of the earliest popular culture portrayals of Milwaukee as a more accessible springboard to success than the cities of the East. Harris grew up in Milwaukee and opened his first songwriting office on Grand Avenue at the age of eighteen. His biggest hit, “After the Ball,” was written and first performed in the city. It was the first song to sell more than one million copies, and it became the most recognizable of the mournful ballads emblematic of the first generation of popular songs produced by Tin Pan Alley, the epicenter of nation’s new music publishing industry. Recognizing the importance of owning the rights to his music, Harris established his own publishing company in Milwaukee before relocating to New York. The national entertainment journal Billboard acknowledged the importance of Harris’s hometown in 1921: “Some folks associate Milwaukee with Socialists, others think of it as a synonym for beer…but few persons know that Milwaukee was the cradle of the present type of the popular song.”[4]

National images of Milwaukee as a socialist bastion and haven of German culture—most prominently brewing—were well-established in the early twentieth century. American involvement in two world wars against Germany, along with Prohibition in the 1920s, rendered these major aspects of the city’s identity somewhat suspect for much of the first half of the century. This likely had a limiting effect on references to—and certainly any celebration of—Milwaukee in the nation’s popular culture in those years. Milwaukee Socialists nevertheless attempted to use popular culture to build support, sponsoring circuses and lyceums to raise funds and attract grassroots interest. One such event during World War I invited the scorn of a national columnist for Billboard, who huffed, “These Socialists are indoctrinated with so much and so many pro-Germanisms that they are at heart anti-Americans.” In what was presented as an equally scathing critique, the writer ridiculed both the event’s scant turnout and the protest of one attendee that in a city like Milwaukee, there were many other things going on. “Well, Bud,” the journalist jabbed, “Chicago is some size and we run a three-ring circus here and manage to get the fact known that there is a Chautauqua in town.”[5]

While Milwaukee was among the nation’s top fifteen largest cities with a population that grew steadily through the first third of the twentieth century, it retained a popular reputation as more town than metropolis, particularly in comparison with nearby Chicago. In a 1939 profile, Variety (the trade magazine of the entertainment industry) offered its assessment of the city: “Largely composed of German and Central European origin, it specializes in a ‘gemuetlich’ type of living—i.e., a contented, conservative, and yet mildly jovial existence. Because of the big emphasis on family and fraternal life, plus the innate dislike of this type of population to spend money on a binge, Milwaukee is an atrocity as a theatre city. That goes for night clubs, too. Anyone who doesn’t pull in the sidewalk at 9 p.m. is not a true native.”[6]

The image of Milwaukee as family friendly—in contrast with popular perceptions of cities as dens of temptation and iniquity—was on full display in the 1927 feature film The Way of All Flesh. Main character August Schiller was a respected Milwaukee banker, loyal husband, devoted father, and champion bowler. All of this unravels once Schiller leaves the city for the first time since his honeymoon, when his bank dispatches him to Chicago to deliver securities. During a night of drunken revelry aboard the southbound train, a temptress steals his bonds, sending him on a dramatic downward spiral that strips him of both his virtue and his family. Emil Jannings’s portrayal of Schiller earned the first Academy Award for Best Actor in motion picture history.[7]

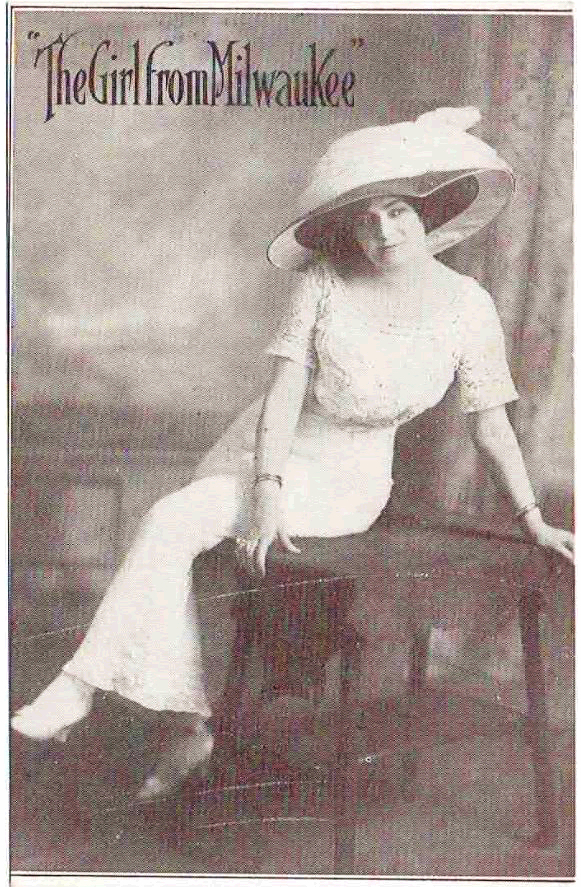

Evocations of Milwaukee occurred more frequently in the world of popular music than in film. An enigmatic young contralto singer known only as “The Girl From Milwaukee” was an attraction on the vaudeville circuit. She toured the country for a decade without revealing her true identity, a novelty which, in combination with her beauty and vocal talent, lent a rare air of exoticism to the city’s image. In previewing her first appearance in Southern California, the entertainment columnist of the Los Angeles Times wagged, “If she takes after Milwaukee’s most famous product, she will be bright, sparkling, clear, effervescent, and altogether palatable. She ought to dress in amber, wear frothy creations and…remember that Milwaukee products are not of much use when ‘bottled up.”” Irish singer and jester Dan McAvoy, another vaudeville performer, wrote and performed a stereotype-laden ditty titled “The Beer That Made Milwaukee Famous,” the refrain of which left “all New York drunk.” George and Ira Gershwin composed “My Cousin in Milwaukee” for the Broadway play Pardon My English, a spoof of Prohibition set in Germany in which the only legal beverages were wine and beer. While the production was short-lived (it proved anachronistic when it opened shortly after Prohibition ended), the song would live on and was later recorded by jazz great Ella Fitzgerald.[8]

Beer was indeed “what made Milwaukee famous” in the popular mind, and the city’s breweries, from the dawn of modern advertising in the late nineteenth century, sought to strengthen the linkage. Schlitz licensed the slogan “The Beer That Made Milwaukee Famous” in the 1890s, and the city’s other breweries adopted enduring advertising campaigns that regularly reminded consumers where their product originated. In the postwar era, television advertisements for beer became a staple of network broadcasts. The catchy jingle for Miller’s “High Life,” would not let viewers forget that it was brewed “carefully, distinctively, wonderfully, exclusively, in Milwaukee!”[9]

Milwaukee breweries recognized early on the natural affinity between their trade and aspects of the entertainment industry. After a downtown opera house he had purchased was destroyed by fire, Frederick Pabst directed the construction of a new state-of-the-art performance space, the Pabst Theater, in 1895. One year later the Schlitz Palm Garden was completed and played host to musical acts. The symbiotic relationship between the two industries continued thereafter, interrupted only by Prohibition. In the 1950s, television advertisements for beer ran during sporting events, the most popular of which were baseball and boxing. In the 1970s, Miller elevated the use of former athletes as pitchmen to an industry standard with its long-running, humorous campaign for Lite Beer. Milwaukee breweries would continue their role in facilitating entertainment by sponsoring stages at the city’s new Summerfest music festival, launched in the late 1960s. Eventually they also purchased naming rights to a new baseball stadium (Miller Park) and renovated auditorium (Miller High Life Theatre).[10]

Milwaukee was so synonymous with beer that it became an instantly recognizable metaphor for drinking when invoked in song lyrics. Perhaps unsurprisingly, references to the working class beverage appeared most frequently in country and western music. Singer Jerry Lee Lewis scored a hit in the 1960s with the song “What’s Made Milwaukee Famous (Has Made a Loser Out of Me),” and vocalist George Jones produced two Milwaukee-themed songs, reaching the charts with “Milwaukee, Here I Come” and later recording “They’ve Got Millions in Milwaukee,” in which he regretfully crooned, “If I only had a penny, for all the suds I’ve soaked, I might even own me a brewery, instead of being broke.”[11]

Milwaukee attained its greatest national visibility in the late 1950s and early 1960s, and perceptions of the city in this era would prove enduring. The 1960 census recorded the highest population total (741,324) and rank (11th) in its history. The city’s manufacturing economy boomed for much of the decade, with the wages of the average industrial laborer doubling between 1946 and 1956. The city seized the national spotlight when the upstart Milwaukee Braves defeated baseball’s defending champions and perennial powerhouse New York Yankees in the 1957 World Series. The team’s devoted fan base rallied around the rumor that the Yankees—the ultimate big city franchise—privately called Milwaukee “Bushville,” a denigrating nickname suggesting that the city was more properly fit for a minor league team, and the Braves’ victory was celebrated by many nationally as an underdog triumph. Milwaukee also became the epicenter of the nation’s political world in the early stages of the hotly contested 1960 presidential election, as rising political star John F. Kennedy first demonstrated his national viability by defeating neighboring Minnesota Senator Hubert Humphrey in the Wisconsin Democratic primary. The Milwaukee of these years once again appeared on the national radar as a place of opportunity for working class Americans, a humane alternative to larger urban centers, but indeed, a “big league” city.[12]

Popular images of Milwaukee in this era would be immortalized in television shows developed a decade later. Amidst the turmoil, uncertainty, and cynicism of the Vietnam-Watergate era, a wave of popular nostalgia for the seemingly less complicated and more carefree 1950s swelled. Tom Miller, the head of development at Paramount, sought to capitalize on the zeitgeist by casting Ron Howard—known to audiences for his childhood role in the long running paean to small town America, The Andy Griffith Show—in a situation comedy focused on the middle class family of studious and likeable high schooler Richie Cunningham. The show was set in an unnamed Midwestern locale during its first season, but from the 1974-75 season onward it would take place in Milwaukee. Miller was a native of the North Shore suburb of Whitefish Bay, and he modeled aspects of the show—most prominently Arnold’s Drive-In—on memories from his youth. The show’s most popular character was an ultra-cool, leather jacket wearing biker named the “Fonz.” Upending threatening Fifties images of motorcyclists as delinquent gang members, the benevolent Fonz defended “nerds” and other misfits, becoming the centerpiece of the considerable merchandising of the show.[13]

Happy Days emerged as a ratings stalwart and it generated an equally popular spinoff, Laverne and Shirley, a show about the madcap antics of two young single women working at the fictional “Shotz Brewery.” The endearing characters and reassuring plotlines of both shows, along with the heavy marketing to wistful Baby Boomers and their children, fashioned popular notions of Milwaukee as the idealized Middle American community in the country’s supposed “golden age” of the late 1950s and early 1960s. This nostalgia was reinforced when the main characters in the successful 1992 comedy film Wayne’s World recreated the iconic opening sequence of Laverne and Shirley (replete with scenes of Milwaukee’s city hall and a beer bottling line) and received a hilarious deadpan lesson in the city’s history from their hero, rock star Alice Cooper.[14] In subsequent decades many Milwaukeeans sought to modernize the city’s image and leave what they saw as the two-dimensional nostalgia of Happy Days behind. Nevertheless, in 2008 the city officially embraced it, commissioning a RiverWalk sculpture dubbed “The Bronze Fonz” that quickly became a downtown tourist attraction.[15]

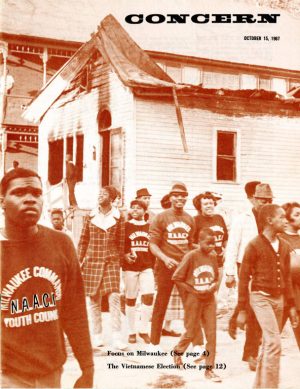

Despite the Hollywood-generated images of a romanticized Milwaukee, beginning in the mid-1960s, events revealed dramatically the city’s deep racial and class divides. Postwar prosperity had been directed disproportionately—in large part by preferential governmental housing policies—toward working class whites, and the city’s relatively small percentage of citizens of color were left confined to an “inner core” of the least desirable housing on the city’s North Side. With Milwaukee’s black population ballooning dramatically in the 1960s as a result of the promise of manufacturing jobs, living conditions grew intolerable. Public schools and housing in African American neighborhoods, already inferior, were increasingly overcrowded. In the midst of the nation’s burgeoning Civil Rights Movement, community leaders sought to have their concerns addressed, to little avail. Frustrations boiled over in the summer of 1967. In Milwaukee, as it would in Detroit, Newark, and elsewhere, urban unrest took the form of open rebellion against the dramatically unequal conditions that belied the city’s the self-image of a contented community of Gemütlichkeit.[16]

The racial divide in Milwaukee gained relatively more popular attention as a result of the leading role played by a white Roman Catholic priest named Rev. James Groppi. Groppi was part of an Italian working class family that by the postwar era finally felt secure in its assimilation into the civic and economic life of the city. Among those that did not join in the suburban exodus beginning in the 1960s, many Milwaukeeans of more recent European descent (the children of southern and eastern European immigrants who had faced discrimination earlier in the century) felt threatened by urban renewal and freeway projects that tore into their South Side neighborhoods. They felt even more endangered by the arrival of growing numbers of African Americans, whom they saw as economic competitors. The magnetic priest became a figure of scorn for these white ethnics and others opposed to change, and he became a national media sensation. In the late 1960s, even as he sought to promote the leadership efforts of African Americans themselves, Groppi became the national face of the city’s racial strife. His polarizing prominence drew frequent national media coverage and social commentary. It also helped attract the participation and spotlight attendant to a major celebrity when comedian and civil rights activist Dick Gregory embraced Groppi and the Milwaukee movement, joining in their open housing demonstrations of 1967.[17]

Tragically, the movement of the 1960s and beyond has not been able to change the course of the city’s segregated patterns of inequality, which a half-century later have only deepened. As the urban deindustrialization of the 1970s and beyond produced more virulent economic competition, frustration, and new manifestations of racism, it also gave rise to the musical genre of Hip-Hop, which offered African Americans new ways to express their experience culturally. As was the case in other aspects of life, Black Milwaukeeans lacked an equal measure of cultural infrastructure, forcing them to transform the city into what one journalist called “a DIY Hip-Hop haven.” The city did produce one resonant popular hit when Coo Coo Cal’s “My Projects,” topped the Billboard rap chart for nine weeks and broke into the top 100 pop chart in the late summer of 2001. The terrorist attacks on September 11 of that year would soon, however, subsume serious civic debate over the Milwaukee artist’s lament for some time. Nationwide popular attention would not return to this aspect of the city’s identity until a series of studies beginning in 2011 revealed Milwaukee to be the nation’s most thoroughly segregated city. Keith McQuirter’s 2016 documentary film Milwaukee 53206 examined the impact on families in the North Side neighborhood which many people believed had become the most incarcerated zip code in the U.S., helping to refocus a national spotlight on the city’s most pernicious and enduring problem.[18]

As the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s imbued African Americans and other citizens of color with racial pride and increased desire to explore their family and cultural histories, it had the unexpected consequence of contributing to a similar interest on the part of Americans of European descent in the 1970s. While Milwaukee had never really shed its prominent connection to its German roots, Mayor Henry Maier pushed for a renewed embrace of the city’s German heritage and the ideal of Gemütlichkeit, which was central to his vision of Milwaukee as the city of festivals. This dovetailed with grassroots community efforts to develop ethnic festivals in the late 1970s, beginning with Festa Italiana and Mexican Fiesta and followed soon thereafter by German Fest, Irish Fest, Polish Fest, African World Festival, Indian Summer, Asian Moon, and other festivals, all of which utilized the lakefront park renamed for Maier in 1986. The festivals featured music, dance, and other aspects of folk culture, and in the words of historian John Gurda they became “a party that members of one group threw for everyone else.” These modernized and diversified examples of “Gemütlichkeit in several languages” reflected a city striving—in the face of considerable social and economic challenges—to fulfill the most noble aspect of its popular identity.[19]

Footnotes [+]

- ^ Horatio Alger, Jr., Julius the Street Boy (or Life in the West) (New York, NY: A.L. Burt, 1874).

- ^ Edna Ferber, Dawn O’Hara: The Girl Who Laughed (New York, NY: Frederick A. Stokes, 1911); Erika Janik, “Appleton Raised, Pulitzer Winner Edna Ferber Born This Week in 1885,” last accessed April 14, 2019.

- ^ Mark Rubin, “Charlie Poole: The Man at Country Music’s Roots,” Sing Out! 49, no. 3 (Fall 2005): 18-24, ProQuest International Index to Music Periodicals (IIMP).

- ^ Charles K. Harris, After the Ball: Forty Years of Melody, An Autobiography of Charles K. Harris (New York, NY: Frank Maurice, Inc., 1926); “Chas. K. Harris: King of the Tearjerker,” The Parlor Song Academy website, November 2001, last accessed April 14, 2019; E.M. Wickes, “It Started in Milwaukee,” The Billboard, July 23, 1921.

- ^ Fred High, “Lyceum & Chautauqua: A Chop Suey Chautauqua,” The Billboard, September 1, 1917.

- ^ Edgar A. Grunwald, “Milwaukee: A Show Business Gag,” Variety, December 27, 1939.

- ^ “New Pictures: Jul. 11, 1927,” Time, July 11, 1927; “The Way of All Flesh,” AFI Catalog of Feature Films website, last accessed April 14, 2019.

- ^ Zip, “Goodwin as Fagin to Start on Road Tour,” Los Angeles Times, April 5, 1913; “The Beer That Made Milwaukee Famous,” The Lester S. Levy Sheet Music Collection, Johns Hopkins Sheridan Libraries & University Museums website, last accessed April 14, 2019.

- ^ Amy Mittelman, Brewing Battles: A History of American Beer (New York, NY: Algora Publishing, 2008), 53-54; “Vintage Miller High Life Beer Commercial,” YouTube video, 0:58, posted by beerdistro, December 14, 2009, last accessed April 14, 2019.

- ^ John Gurda, The Making of Milwaukee (Milwaukee: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 1999), 170, 189; Mittelman, Brewing Battles, 324.

- ^ “What’s Made Milwaukee Famous (Has Made a Loser Out of Me),” Jerry Lee Lewis│Chart History, Billboard website, last accessed April 14, 2019; “Hot Country Songs: The Week of November 9, 1968,” Billboard website, last accessed April 14, 2019; “They’ve Got Millions in Milwaukee,” Genius website, last accessed April 14, 2019.

- ^ Gurda, The Making of Milwaukee, 351-352.

- ^ “Show ‘Moves’ to Milwaukee,” Minneapolis Star-Tribune, September 15, 1974; Glendale Drive-In Served as Inspiration For Hangout in ‘Happy Days,’” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, August 19, 2008.

- ^ The scene of Alice Cooper in Wayne’s World is available on Youtube at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nRCTc6stICc, last accessed April 14, 2019.

- ^ Lainey Seyler, “For 10 Years, the Bronze Fonz Has Been a Favorite for Visitors to Milwaukee,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, August 17, 2018.

- ^ Patrick D. Jones, The Selma of the North: Civil Rights Insurgency in Milwaukee (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 9-79), 143-168; Syreeta McFadden, “White Milwaukee Lied to Itself for Decades, and in 1967 the Truth Came Out,” Timeline website, August 2, 2017, last accessed April 14, 2019.

- ^ Jones, The Selma of the North, 169-209.

- ^ “Coo Coo Cal│Chart History,” Billboard website, last accessed April 14, 2019; Tara Mahadevan, “Milwaukee’s Best: Wisconsin City Has Become a DIY Hip-Hop Haven,” Noisey website, October 2015, last accessed April 14, 2019. A recent report by historian Marc Levine finds that 53209 was not even in the top 250 most incarcerated zip codes in the United States, even as it did reflect a wide array of problems associated with concentrated disadvantage: Marc V. Levine, “Milwaukee 53206: The Anatomy of Concentrated Disadvantage in an Inner City Neighborhood, 2000-2017” (Milwaukee: University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Center for Economic Development, 2019), pp. 7-8, last accessed April 14, 2019.

- ^ Gurda, The Making of Milwaukee, 401-404.

For Further Reading

Anderson, Harry. “The Women Who Helped Make Milwaukee Breweries Famous.” Milwaukee History 4, no. 3-4 (1981): 66-78.

Ashby, LeRoy. With Amusement for All: A History of American Popular Culture Since 1930. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 2006.

Billboard.

Corzine, Nathan Michael. “Right at Home: Freedom and Domesticity in the Language and Imagery of Beer Advertising, 1933-1960,” Journal of Social History 43, no. 4 (Summer 2010): 843-866.

Cullen, Jim, ed. Popular Culture in American History. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 2013.

Gurda, John. The Making of Milwaukee. Milwaukee: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 1999.

Jones, Patrick D. Selma of the North: Civil Rights Insurgency in Milwaukee. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009.

Marcus, Daniel. Happy Days and Wonder Years: The Fifties and the Sixties in Contemporary Cultural Politics. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2004.

Mueller, Theodore. “Milwaukee’s German Cultural Heritage.” Milwaukee History 10, no. 3 (September 1987): 95-108.

Nelson, Sheila. “Milwaukee Beer: It Made a City ‘Famous.’” Wisconsin Then & Now 14, no. 7 (1968): 1-5.

Povletich, William. “When the Braves of Bushville Ruled Baseball.” Wisconsin Magazine of History 90, no. 4 (Summer 2007): 2-14.

Variety.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.