Milwaukee radio developed as a result of cooperation between educational institutions and commercial media. These public and private entities built the technology necessary for radio to flourish and developed the programming that spread across the airwaves. AM radio arrived in Milwaukee in the early 1920s, followed by FM radio in the early 1940s, and then HD radio and streaming audio in the early twenty-first century. AM (or amplitude modulation) radio could reach long distances, but with greatly diminished quality. FM (or frequency modulation) radio did not experience a similar reduction in sound quality since its audio came from changes in frequency rather than amplitude. High Definition (HD) radio broadcasts depended on digital signals to broadcast rather than the analog signals used by AM and FM. Local universities and news stations made possible the spread of AM. Due in part to the advances in radio technology made by the Journal Corporation, local families like the Bartells built FM radio stations that included specialized programming for local listeners, including ethnic groups and sports enthusiasts. More recently, Milwaukee, like other cities, has experienced a massive consolidation of its radio stations.

The 1920s witnessed the birth of radio in Milwaukee and surrounding cities. The University of Wisconsin developed technology that allowed voice broadcasts over the air in Madison in 1919. In early 1922, representatives from the Milwaukee Journal visited University of Wisconsin physicist Earle M. Terry, who ran the university’s WHA radio station, in an attempt to broker a partnership. Unable to reach an agreement, the Journal Corporation sponsored programs on Milwaukee’s new radio stations and worked to create its own station.[1] Realizing the increasing popularity of this new medium, the federal government created the Federal Radio Commission in 1926 and later the Federal Communications Commission in 1934. These commissions approved licenses for new stations and determined the frequencies of the stations.

On April 26, 1922, WAAK became Milwaukee’s first radio station. Owned by the Gimbels Department Store, a 40-foot tower sat atop the department store’s downtown building. Raymond Mitchell, a local musician and producer, found acts from the local theater and music halls to put on the air. In an effort to grow the public’s interest in radios, Gimbels had earphones placed throughout the store in order to entice shoppers to listen to the station and purchase a radio. The station lasted less than one year because Gimbels could not meet new technology guidelines set by the federal government.[2] In June 1922, Kesselman-O’Driscol Music Company began Milwaukee’s second radio station, WCAY. Most of the city’s residents, however, still knew very little about radio. Therefore, during the first Milwaukee Radio Show in June 1922, the Journal Company held a contest to encourage people to build their own radio receivers.[3] By 1924, only 9 percent of Milwaukee’s families owned a radio set, with the majority still in the form of self-assembled radios rather than prefabricated sets. Within ten years, nearly all families in the city owned a radio set. In 1934, furthermore, greater numbers of Milwaukee residents listened to the radio in their cars.[4]

Meanwhile, two Milwaukee-area universities created their own radio stations. At Marquette University, Father John B. Kramer started WHAD, which began broadcasting in September 1922. Broadcasts by students, weather reports, and stock market updates filled the station’s airwaves. The following month, October, the School of Engineering of Milwaukee (now the Milwaukee School of Engineering) and the Wisconsin News newspaper began transmitting under the call letters WIAO, which later became WSOE in 1925.[5]

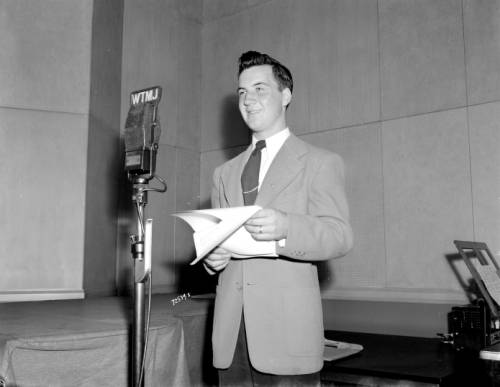

In early 1925, the Journal Company joined with Marquette University to run WHAD. By November 1926, WHAD aired an NBC program headed by Will Rogers, which led 14,000 listeners to ask that the station expand to their area. However, since the station’s transmitter was located within the city, the Journal Company could not meet these demands. For this and other reasons, the Journal Company ended its relationship with WHAD and purchased WKAF in 1927. Soon thereafter, the Journal received a construction permit to build a new radio tower in Brookfield and new call letters, WTMJ, which aired its first programs on July 25, 1927. WTMJ began its affiliation with NBC on August 15, 1927, which remains to this day, and allowed the station to broadcast NBC programs in addition to showcasing local musicians. The radio station began the practice of allowing advertisers to purchase advertising rights for a particular program. The Hearst Corporation’s Wisconsin News took over operation of WSOE in 1927, though the engineering school continued to assist in technical matters. The following year, 1928, WSOE became WISN. In 1930, the Wisconsin News purchased the station and, in April 1932, moved it to the Milwaukee Sentinel building, which Hearst owned, and became an affiliate of CBS News.[6]

By the 1930s, broadcasters began to experiment with high fidelity radio. From the middle to late 1930s, the Journal Company made tremendous strides in improving the quality of radio transmissions.[7] The Journal Company started its first FM station, W9XAO in 1940, with a tower located on the Wisconsin Tower at North 6th Street and West Wisconsin Avenue. W9XAO was purportedly the first FM radio station west of the Allegheny Mountains and among the first five FM stations in the country. The newness of FM radio, however, meant that few people living in Milwaukee had FM radio sets. Therefore, the Journal Company purchased twenty-one radio sets for placement around the city so that the public could listen. With AM, FM, and soon television signals to broadcast, the Journal Company began construction in June 1941 for its “Radio City” broadcasting facility, which included a 300 foot tower, at North Humboldt Boulevard and East Capitol Drive. With another transmitter in Richfield, the station had the furthest reach of all FM stations in the country, reaching listeners as far west as Columbia and Dane counties and into parts of northern Illinois. In the early 1940s, the station broadcast primarily music, with news breaks twice daily, for twelve hours a day. The station stopped producing original programming after it became WTMJ-FM in 1945 and began simulcasting the WTMJ-AM station. As television gained in popularity and since many Americans still could not receive FM signals on their radios, the Journal Company, following the lead of many FM stations across the country, stopped its transmissions of WTMJ-FM in April 1950.[8]

By mid-1958, Wisconsin had twenty FM stations, with two independently operated stations in Milwaukee. Soon after the Journal Company restarted its FM broadcasts in June 1959, the station became the first in Milwaukee to offer stereo broadcasts, which required listeners to tune their AM and FM receivers to WTMJ and WTMJ-FM respectively and place the radios ten feet apart. At the time, in 1959, just under 100,000 Milwaukeeans had FM receivers. By the middle of the following decade, this number more than doubled to over 211,000.[9]

Milwaukee radio also broadcast local and state sports. As it is to this day, WTMJ-AM was the station for coverage of the Packers football games. Beginning in November 1929, sports announcer Russ Winnie used wire reports about the game and recorded sound-effects to tell the listeners about the game. WTMJ did not own the rights to the Packers games until 1943, when the station paid the Packers $7,500 to air the games.[10] WEMP-AM, which first came on the air in 1935, and WEMP-FM played music but also focused on sports. In addition to airing Baseball Reports every half-hour during the week, WEMP offered its fans Marquette University home football and basketball games, every University of Wisconsin basketball game, and hockey games of the Milwaukee Clarks. Most importantly, WEMP broadcast all Brewers games.[11]

Despite the growing popularity of FM radio, AM stations continued to find an audience in Milwaukee. In August 1947, the Bartell family began WEXT, which played polka and other ethnic music. With its studio on Milwaukee’s south side near Jackson Park, John Reddy, Milwaukee’s “polka king,” hosted a program playing polka music. Every Sunday, WEXT leased its studio to a group that aired a variety of foreign-language shows. The station also became famous for singing commercials rather than just reading them from a script. However, limited to airing programs during the daytime and barely earning a profit, Gerald Bartell began the process of moving the radio station to another frequency. More importantly, he also put forth the idea of airing a “Top 40” program on the station. On September 5, 1950, the Bartell family started broadcasting under the call letters WOKY. Unlike its predecessor station, WOKY aired programming all day. In addition to broadcasting Marquette University sports, the station aired a program narrated by Gerald Bartell, Playtime for Children, which reached viewers around the state through syndication. WOKY’s Art Zander offered traffic reports from high above the city during his program, The Safer Route, which was the first of its kind in the city. By late 1952, WOKY was among the top three radio stations in Milwaukee.[12]

Several other stations also aired ethnic programming. First airing on WEMP in 1936, Our Polish Hour with Stanley Nastal eventually moved to WFOX when the station began broadcasts in 1946. In addition to Our Polish Hour, which aired in both the morning and afternoon, Nastal DJed Theater of the Air and the Original Polish Amateur Hour. WFOX reduced its foreign-language programs by the mid-1955 as the station faced financial difficulties and a changing audience. The station also aired The Jewish Hour on Sundays, which included Yiddish songs sung by members of the Jewish Theatre Guild. Another station, WMIL, with Fritz the Plumber at the helm, played polka music.[13] In 1982, while program director for WYMS, Jim Ebner received tremendous feedback after he played polka music to fill in an empty spot in the programming. Several local polka groups responded by sending their albums to the station and WYMS, as a result, began airing a weekly show called Polka Parade. In 2003, the program moved to WEMP at 1250-AM.[14]

WNOV-AM and WMCS-AM, both black-owned, served as the primary radio stations for the African American community in Milwaukee. The former, located on Twentieth Street and Capitol Drive, became WNOV in 1967 and, until 2008, was owned by the African American weekly Milwaukee Courier. R&B, gospel, and hip-hop music, in addition to talk radio programs, filled the airwaves at WNOV. The station hosted important figures in black talk radio, including, until 2007, former alderman Michael McGee. WMCS, owned by former Packers player Willie Davis, broadcast talk radio all day, including programs hosted by Eric Von and Earl Ingram locally and Al Sharpton through syndication. WMCS also aired a show called “Talk of the Town” that allowed for in-depth discussion of local affairs. In early 2013, WMCS ended this format, airing instead popular music.[15]

Due to the efforts of the University of Wisconsin and other local colleges, public radio grew in size in the decades following World War II. While WHA-AM reached Milwaukee, the quality was less than good, so the University of Wisconsin began broadcasting on WHA-FM in 1967. With its move to FM, WHA sought to expand its reach. Thus, on June 30, 1948, WHA started its second radio station, which had its transmitter in Delafield, known as WHAD. Marquette University stopped using the WHAD call signal for its AM station in 1934. WHAD re-aired broadcasts of programs that originated from WHA in Madison. By 1972, however, WHA affiliates began producing their own original programs. In December 1972, for instance, WHAD developed and aired the first such program, Programa Cultural en Espanol for Spanish-speaking listeners in Milwaukee and the surrounding area. WHA and its affiliates organized under the name Wisconsin Public Radio (WPR) in early 1979. Not until July 1989, however, did WPR open a bureau in Milwaukee. The Milwaukee studio held a variety of call-in programs that also aired throughout the state.[16]

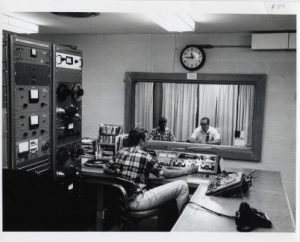

With help from WHA radio engineers, the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee (UWM) developed WUWM, which aired for the first time in September 1964. Since it would be another three years before Congress passed the Public Broadcasting Act of 1967, which created the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, WUWM depended on the College of Letters and Science at UWM for its funding. Run by UWM students, WUWM’s signal reached only the surrounding neighborhoods. Following the passage of the 1967 act, WUWM became the local affiliate of National Public Radio (NPR). In 1971, WUWM updated its studio and hired professional staff. WUWM moved its transmitter to the WITI TV6 tower in 1978, which allowed much of metropolitan Milwaukee to hear the station. Two years later, in 1980, new satellite technology made WUWM programming available to NPR stations across the country. In late 1979, WHA created a news bureau in Milwaukee and began airing WUWM-produced reports. WUWM also aired WPR programs.[17]

WHA and WPR also had a close relationship with Milwaukee Public School-owned WYMS radio, which first aired in March 1973. WYMS was an affiliate of WPR until 1989, when the latter stopped airing its weekday jazz programming. WYMS continued to air jazz during weekdays as well as ethnic programming on the weekends until a 2002 decision by the MPS school board to lay off the staff and end WYMS’s scheduled programming in response to the school district’s budget shortfall. WYMS initially aired programming from WUWM and then picked up the syndicated jazz program JazzWorks. In the following years, the nonprofit Radio for Milwaukee purchased WYMS and, in 2007, turned it into Radio Milwaukee.[18]

After WSOE became WISN in 1932, MSOE continued to produce programming for the station such as Sounds of Science, which discussed technological issues and remained on the air until 1977. WSOE reappeared on the air in 1969, becoming WMSE in 1981.[19] The music played on WMSE is quite diverse due to the fact that volunteer DJs determine what they play. Thus, shows such as Dr. Sushi’s Free Jazz BBQ and Johnny Z’s Chicken Shack fill in slots at the station.[20]

Beginning in the 1980s, Milwaukee’s airwaves were increasingly filled with talk radio hosts offering their own political perspectives. As a result of the Federal Communications Commission’s decision to overturn the Fairness Doctrine in 1987, radio stations no longer had to provide equal time for individuals holding opposing views in relation to a particular topic.[21] Conservatives, in particular, have taken to the airwaves in Milwaukee. In 1989, Mark Belling joined WISN’s 1130-AM and currently hosts an afternoon show. At WTMJ’s 620-AM station, Charlie Sykes, who joined the network in 1992, also hosted a midday program until 2016.[22] WTMJ is also home to Jeff Wagner.[23]

With the Telecommunications Act of 1996, radio station owners no longer faced restrictions in regard to how many stations they could own. As a result, by 2003, four radio station companies owned approximately 86 percent of the market share in Milwaukee. At one point in the early 2000s, Clear Channel, a dominant player in Milwaukee’s radio business, owned nearly 1,200 radio stations nationwide.[24] In the early 2000s, Clear Channel set out its plan to convert its radio stations to digital audio feeds, which allowed for high-definition (HD) radio. At the same time, many radio stations turned to internet streaming to broadcast their programming over the worldwide web. In 2001, WPR offered its listeners the opportunities to stream its radio networks and in late 2005 WHA offered HD radio, with WHAD becoming HD the following year.[25]

Footnotes [+]

- ^ Randall Davidson, 9XM Talking: WHA Radio and the Wisconsin Idea (Madison, WI: The University of Wisconsin Press, 2006), 16; Dick Golembiewski, Milwaukee Television History: The Analog Years (Milwaukee: Marquette University Press, 2008), 37-38.

- ^ Lewis W. Herzog, “The Beginnings of Radio in Milwaukee,” Historical Messenger of the Milwaukee County Historical Society 11 (December 1955): 11.

- ^ Golembiewski, Milwaukee Television History, 38.

- ^ Herzog, “The Beginnings of Radio in Milwaukee,” 11; Lewis W. Herzog, “Radio in Milwaukee, 1929-1955,” Historical Messenger of the Milwaukee County Historical Society 12 (March 1956): 9.

- ^ Golembiewski, Milwaukee Television History, 38-39.

- ^ Golembiewski, Milwaukee Television History, 39-40, 223; Herzog, “The Beginnings of Radio in Milwaukee,” 15.

- ^ The Journal Company asked for and received on March 30, 1934 a permit to begin an “Apex” station, W9XAZ. After a change in frequency in 1936, residents of Los Angeles, England, and New Zealand could hear programs from W9XAZ. Originally sharing programs with its AM radio sister station WTMJ, W9XAZ began in late 1936 to offer Marquette University home basketball games, boxing contests held at the Eagles’ Club, and other events. No other Apex stations offered original programming. By 1939, W9XAZ was no longer on the air. See Golembiewski, Milwaukee Television History, 23-24, 40-41; “Milwaukee Journal Stations Records, 1922-1997,” Wisconsin Historical Society finding aid, accessed March 27, 2015; Christopher H. Sterling, “WTMJ-FM, the Milwaukee Journal FM Station, 1939-1966” (Master’s thesis, University of Wisconsin, 1967), 18-20, 24, 29-30, 46, 50, 84-86, 93-94. See also Christopher H. Sterling, “WTMJ-FM: A Case Study in the Development of FM Broadcasting,” Journal of Broadcasting 12 (Fall 1968): 341-352.

- ^ Golembiewski, Milwaukee Television History, 23-24, 40-41; “Milwaukee Journal Stations Records, 1922-1997,” Wisconsin Historical Society finding aid, accessed March 27, 2015; Sterling, “WTMJ-FM, the Milwaukee Journal FM Station, 1939-1966” (18-20, 24, 29-30, 46, 50, 84-86, 93-94. See also, Sterling, “WTMJ-FM”: 341-352.

- ^ Sterling, “WTMJ-FM, the Milwaukee Journal FM Station, 1939-1966,” 100-109, 111-113, 119.

- ^ Davidson, 9XM Talking, 222-223.

- ^ Bill Thompson, “The Milwaukee Radio Market,” Broadcasting, June 6, 1949, 9.

- ^ Golembiewski, Milwaukee Television History, 160-162; David T. MacFarland, “The Development of the Top 40 Radio Format” (PhD diss., University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1972), 239; Charles F. Ganzert, “Hot Clocks, Jingles, and Top Tunes: The Bartell Group Stations and the Development of Top 40 Radio,” Popular Music and Society 21 (1997): 55, 58.

- ^ “Stanley I. Nastal Papers, 1922, 1934-1954,” University of Wisconsin Digital Collections finding aid, accessed on April 11, 2015; Thompson, “The Milwaukee Radio Market,” 10.

- ^ Polka Parade website, accessed April 11, 2015.

- ^ Eugene Kane, “WMCS 1290 Silences the Talk,” OnMilwaukee.com, February 26, 2013, accessed on April 25, 2015; Eugene Kane, “The Other Black Radio Station in Town: WNOV up to the Challenge,” OnMilwaukee.com, March 1, 2013, accessed on April 25, 2015.

- ^ Davidson, 9XM Talking, 153-154, 189, 302, 305.

- ^ “WUWM’s History,” Internet Archive, 2007, accessed March 27, 2015; Davidson, 9XM Talking, 180-181, 312-313.

- ^ Davidson, 9XM Talking, 308.

- ^ “New Digital Collection Highlights ‘A History of Radio at MSOE,’” accessed on April 11, 2015.

- ^ N. Jakob Rollefson, “‘Community in Heavy Rotation’: Music-Formatted Public Radio and the Conception of the Audience” (MA thesis, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2011), 35, 38-40.

- ^ Christopher H. Sterling and Michael C. Keith, Sounds of Change: A History of FM Broadcasting in America (Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 2008), 168.

- ^ Hadas Gold, “Charlie Sykes to End His Radio Show,” Politico website, October 4, 2016, accessed July 15, 2017.

- ^ Brien Farley, “Milwaukee Talk Radio’s (Rather) Fertile Landscape,” OnMilwaukee.com, accessed on April 9, 2015.

- ^ Sterling and Keith, Sounds of Change, 178-179, 182-183; Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation, Media Ownership: Hearing before the Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation, 108th Cong., 1st sess., January 30, 2003, 6.

- ^ Sterling and Keith, Sounds of Change, 200-205; “WPR’s Tradition of Innovation,” Wisconsin Public Radio website, accessed on April 10, 2015.

For Further Reading

Davidson, Randall. 9XM Talking: WHA Radio and the Wisconsin Idea. Madison, WI: The University of Wisconsin Press, 2006.

Ganzert, Charles F. “Hot Clocks, Jingles, and Top Tunes: The Bartell Group Stations and the Development of Top 40 Radio.” Popular Music and Society 21 (1997): 51-62.

Golembiewski, Dick. Milwaukee Television History: The Analog Years. Milwaukee: Marquette University Press, 2008.

Herzog, Lewis W. “The Beginnings of Radio in Milwaukee.” Historical Messenger of the Milwaukee County Historical Society 11 (December 1955): 11-15.

Herzog, Lewis W. “Radio in Milwaukee, 1929-1955.” Historical Messenger of the Milwaukee County Historical Society 12 (March 1956): 9-12.

Macfarland, David T. “The Development of the Top 40 Radio Format.” PhD diss., University of Wisconsin, 1972.

Rollefson, N. Jakob. “‘Community in Heavy Rotation’: Music-Formatted Public Radio and the Conception of the Audience.” MA thesis, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2011.

Sterling, Christopher H. “WTMJ-FM: A Case Study in the Development of FM Broadcasting.” Journal of Broadcasting 12 (Fall 1968): 341-352.

Sterling, Christopher H. “WTMJ-FM, the Milwaukee Journal FM Station, 1939-1966.” MA thesis, University of Wisconsin, 1967.

Sterling, Christopher, and Michael C. Keith. Sounds of Change: A History of FM Broadcasting in America. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 2008.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.