Milwaukee has had newspapers and media catering to the Wisconsin black community since the 1890s. From the beginning these media outlets sought to increase both the appeal of Milwaukee as a destination for African Americans and as an avenue of racial progress. In April of 1892, two white men, George A. Brown and Thomas Jones, published the Wisconsin Afro-American. This paper functioned as a recruitment circular to bring African Americans north for work and only lasted a few months. Six years later, in 1898, Milwaukee became home to the first indigenous black press for the state of Wisconsin, when former Mississippi slave Richard B. Montgomery debuted his Wisconsin Weekly Advocate.

Montgomery’s paper, like its predecessor, appealed to black southerners to come to Wisconsin for work. However, while Brown and Jones’s paper represented employment agencies, the Wisconsin Weekly Advocate’s owners also owned Colored Helping Hand Intelligence Office (AKA the Help and Hand Society), an employment agency. In addition to running ads for their agency, Montgomery, assisted by A.G. Burgette, used the paper as a platform to advocate for Booker T. Washington’s ideology of merit and support black businesses. Montgomery hired Wisconsin’s first female African-American journalist, Lillian Maxey, the paper’s “city editress.” However, Montgomery’s devotion to Washington also led his paper to engage in editorial conflicts with black weeklies in other cities who criticized Washington’s policies. Despite Montgomery’s championing of black self-help, he also often underplayed the existence of racial discrimination.[1] A financial crisis in 1900 led the printing of the Wisconsin Weekly Advocate to become irregular after 1901, and the paper ceased production totally in 1907.

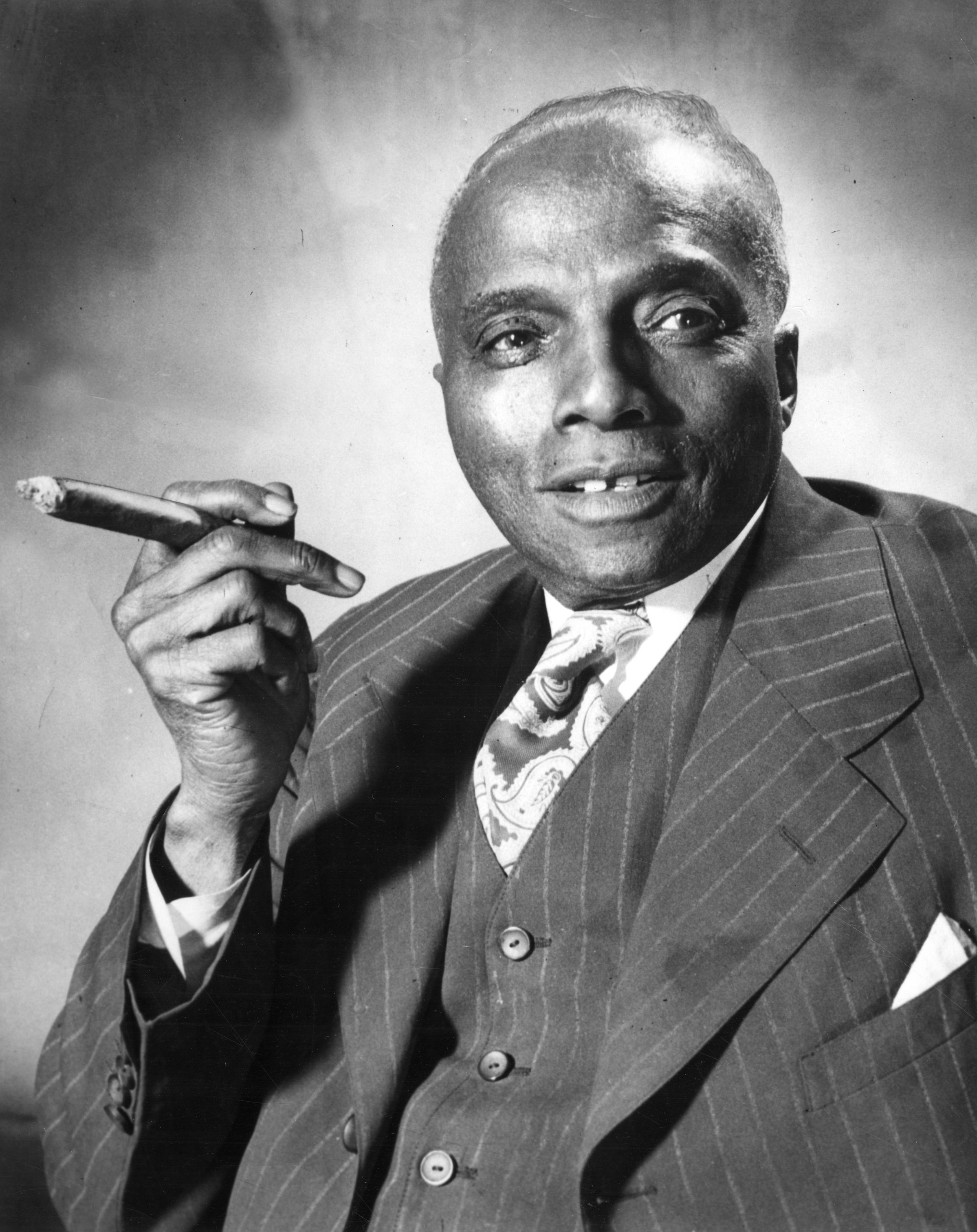

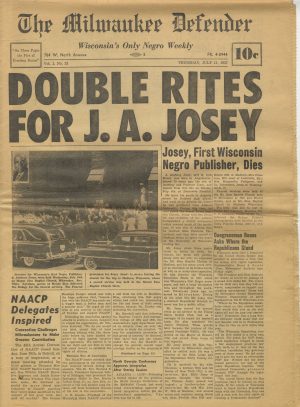

It was almost a decade before another African American owned newspaper emerged in Milwaukee. J. Anthony Josey, a native of Augusta, GA was a graduate of Atlanta University and worked as a co-editor of the Atlanta Independent during his time there. Josey merged his Wisconsin Weekly Blade with the Milwaukee-based Wisconsin Enterprise in 1916 to form the Wisconsin Enterprise-Blade. Josey, with the help of co-editors L.J Quisely and Z.P. Smith and contributing editor George DeReef, maintained a publication presence for nearly thirty years.[2] Under Josey’s editorial leadership, the Wisconsin Enterprise-Blade struck a more militant tone. He editorialized against African-American enlistment in World War I and confronting the Milwaukee Journal’s racial biased coverage. Josey’s editorial crusade against discrimination was not without controversy. In the 1930s Josey refused to endorse an African-American candidate for city office. He saw dismal prospects of winning and considered the white incumbent an ally to the African American community. By the 1940s Josey’s paper fully endorsed African-American candidates; but it had ceased publication by the time Le Roy Simmons was elected to the State Assembly in 1944.

After the demise of the Wisconsin Enterprise-Blade, a succession of African-American newspapers attempted to fill the void. None of them lasted more than a couple of years. The exception was the Milwaukee Defender, an offshoot of the Chicago Defender, published from 1956 until 1958. During the 1960s Wisconsin’s African-American community saw six newspapers launch. However, only two lasted through the decade. The Milwaukee Star published under a series of names from 1961 until 2005. The Milwaukee Courier, founded in 1964, is still in publication.[3] Both of these papers benefitted from the journalistic skills of Walter Jones, who began his career in Milwaukee working for the Star before joining the Courier in 1967. Jones’s attacks against racism in Milwaukee gave voice to the rigidly segregated community throughout the turbulence of the 1960s. In 1973, the Courier became a multimedia conglomerate, purchasing radio station WNOV-AM and changing the station’s country music format towards a variety of African-American programming

As Milwaukee’s African American community grew, two more papers expanded the black press further. In 1976 the Milwaukee Community Journal was founded by Patricia O’Flynn Thomas. In 1985 publisher Nathan Conyers renamed the Christian Times the Milwaukee Times, reorienting its coverage to serve black readers in the greater southern Wisconsin and Northern Illinois region.

By the 1970s, Milwaukee’s television stations also reflected the growing importance of the African-American community in Milwaukee media. In 1972, WITI-TV, Channel 6, hired the city’s first African-American news anchor, John Gardner. WTMJ followed, hiring Bill Taylor away from WNOV radio.[4] The Wisconsin Black Media Association, the local chapter of NABJ-National Association of Black Journalists, has a strong presence in Milwaukee media.[5] Milwaukee PBS hosts “Black Nouveau,” described as a program to “promote positive images, interviews and profiles of African-American movers and shakers.”[6] Wisconsin Black Historical Museum founder Clayborn Benson worked behind the camera at WTMJ for thirty-nine years.[7]

In the twenty-first century, the Milwaukee area supports both a vibrant print and media presence aimed specifically at the African-American community and their interests in achieving justice and equity in Milwaukee, and also a significant presence of African Americans professionals within Milwaukee’s “mainstream media” environment.

Footnotes [+]

- ^ Genevieve G. McBride, “The Progress of ‘Race Men’ and ‘Colored Women’ in the Black Press in Wisconsin, 1892-1985,” in The Black Press in the Middle West, 1865-1985 (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1996), 325-48; Joe William Trotter, Jr., Black Milwaukee: The Making of an Industrial Proletariat, 1915-1945, 2nd ed. (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2007).

- ^ Genevieve G. McBride and Stephen R. Byers. “The First Mayor of Black Milwaukee: J. Anthony Josey.” Wisconsin Magazine of History 91, no. 2 (Winter 2007-2008): 2-15.

- ^ For a chronological listing of all African American newspapers available in Milwaukee since 1916, see the listing provided by the Milwaukee Public Library’s Periodicals Department, https://www.mpl.org/content/pdfs/MilwaukeeAfricanAmericanNewspapersMagazinesatMPL.pdf, last accessed January 31, 2019.

- ^ Nate Grimm, “Anchoring His Life,” Wisconsin People & Ideas 53, no. 1 (Winter 2007): 62-72.

- ^ See the Wisconsin Black Media Association Facebook page, last accessed January 31, 2019. In 2018 Sharon Sims, of Today’s TMJ4 [WTMJ-TV] served as WBMA president.

- ^ Black Nouveau, Milwaukee PBS website, accessed November 18, 2018.

- ^ Bobby Tanzilo, “Urban Spelunking: Wisconsin Black Historical Society and Museum,” OnMilwaukee.com, December 12, 2017, accessed November 18, 2018; “African American History with Clayborn Benson,” Now@MPL, Milwaukee Public Library website, February 4, 2014, accessed November 18, 2018.

For Further Reading

Grimm, Nate. “Anchoring His Life,” Wisconsin People & Ideas 53, no. 1 (Winter 2007): 62-72.

McBride, Genevieve G. “The Progress of ‘Race Men’ and ‘Colored Women’ in the Black Press in Wisconsin, 1892-1985.” In The Black Press in the Middle West, 1865-1985, edited by Henry Lewis Suggs, 325-48 Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1996.

McBride, Genevieve G. and Stephen R. Byers. “The First Mayor of Black Milwaukee: J. Anthony Josey.” Wisconsin Magazine of History 91, no. 2 (Winter 2007-2008): 2-15.

Trotter, Joe William, Jr. Black Milwaukee: The Making of an Industrial Proletariat, 1915-1945, 2nd ed. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2007.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.