The United States has fought three major wars since Milwaukee became a city. Milwaukee’s wartime history reflects its evolution from a frontier town to an industrial center, highlights the city’s changing political priorities and gender roles, and provides a case study of the stresses and strains war has put on American cities since the mid-nineteenth century.

The Civil War

Milwaukeeans were deeply involved in the political issues of the 1860 presidential campaign but not unified about them. While much of the state supported Abraham Lincoln and the Republicans, Milwaukee had a strong Democratic streak, especially among the Germans. Stephen A. Douglas and Abraham Lincoln both visited Milwaukee. Local papers supported one or the other and outdoor meetings, parades, and bonfires kept the populace interested.[1]

Once it began, the Civil War spurred economic growth. City farm-machinery producers like Milwaukee Harvester and J.I. Case helped make wheat king, to the benefit of merchants along the harbor and grain processors along the Menomonee River. Military and civilian demands for leather production nearly doubled the number of tanneries. Pork-packing facilities also experienced growth, and beer production increased by almost 20,000 barrels a year.[2]

But the war also sparked conflict, especially over military conscription. Numerous protests—often described as “riots” by authorities—broke out in the four county area when the state initiated a draft for militia volunteers in 1862, and when the federal government began conscription in the summer of 1863. The most notable disturbance occurred in Port Washington in late 1862; eight companies of soldiers were required to end it.[3]

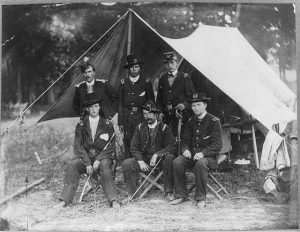

Support for war aims were also commonly expressed in the streets. Immediately following the Southern secession, leaders in Milwaukee called for a mass outdoor meeting. Community bands joined militia units on parade, ministers prayed, and political leaders gave speeches meant to inspire the crowds. Meetings represented the many points of view of the community. They supported military activities, helped the city mourn its losses, stimulated donations for the support of families of the volunteers, presented protests against policies, and punctuated the spirited presidential election of 1864. During that canvass Milwaukeeans cast 3,175 votes for Abraham Lincoln and 6,875 for George McClellan.[4] Private militia units had been a common sight in the streets even before the Civil War, since ten companies called the city home. The members of these units came from all neighborhoods and included some of the most prominent citizens. Many responded to President Abraham Lincoln’s call for troops, issued in an April 15, 1861, telegram to Governor Randall that required the state to provide a regiment (about 1,000 men) for the Union war effort. Militiamen were joined by other volunteers coming to the city to receive preliminary training at one of the camps swelled the city’s population temporarily. The first of these troops arrived shortly after.[5]

The first volunteers gathered at Camp Scott, named for General Winfield Scott, commander of the Union army, on Spring Street west of Twelfth. The conditions there were so bad that the volunteers preferred to spend their nights in the city; picket lines had to be established to keep the men at camp. Among the other training grounds were Camp Holton, later called Camp Sigel, which was in the First Ward near Lake Michigan, and Camp Washburn, located west of Twenty-seventh Street on the grounds of the Cold Spring racing course.[6]

The most popular unit during the early days of the war was the Milwaukee Light Guard, led by Rufus King, which became part of the 1st Wisconsin Infantry. King eventually commanded the Iron Brigade, which included three regiments from Wisconsin.[7] Other notable units from the four counties included the 24th Wisconsin, which was eventually commanded by nineteen-year-old Col. Arthur MacArthur, Jr., father of Douglas MacArthur; MacArthur coined the state motto of Wisconsin when he led his men into the Battle of Missionary Ridge with the cry “On Wisconsin!” The 26th Wisconsin was recruited from among the German-speaking population of the area, including some members of the earliest Jewish community; it fought in many of the biggest battles of the war, with 265 officers and men dying of wounds or disease. The 15th Wisconsin was the Union’s only Scandinavian regiment. Raised largely in Waukesha County, it was commanded by the Norwegian immigrant and politician Hans Heg, who was killed at the Battle of Chickamauga. Heg was the highest-ranking Wisconsin officer killed during the war.[8]

Back home, women who in peacetime had cared for the poor, for orphaned children, and for other community members requiring assistance, began their wartime work by providing blankets and other supplies when the inefficient army supply system failed to meet demand. To express their respect for the soldiers, they sewed and donated flags and made “Havelock caps” to protect the necks of men going to battle in the South. When they learned that soldiers needed special mittens, women in the city formed a “Mitten Society” and made boxes full of them.[9]

The women also worked through soldiers’ aid societies, which formed in neighborhoods across the city. They contributed, solicited, or bought medical supplies, food, clothing, and other necessity items, then sent them to the United States Sanitary Commission depot in Chicago, where they were warehoused until needed by the army or distributed to other organizations or to local men. They raised money through dinners, entertainments, and fairs. When veterans began returning from the front, the women opened a soldier’s home “in Mrs. Kneeland’s new block, on West Water street” so the men could get a meal and a bed. At war’s end, units came to Milwaukee and were mustered out. It became apparent that a significant number of veterans needed permanent care, so the women organized the huge Wisconsin Soldiers’ Aid Fair in the summer of 1865 that raised more than $100,000. They were eventually convinced to contribute that money to the successful effort to open the Northwestern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers, which opened in 1867. It eventually became part of the Veterans Administration in 1930 and, as part of the Clement J. Zablocki VA Medical Center, remains an important reminder of the Civil War’s effects on Milwaukee.[10]

World War I

The nineteen months during which the United States participated in World War I was one of the most divisive periods in Milwaukee’s history, largely due to the city’s patchwork of ethnic groups. In 1910, more than 75 percent of Milwaukeeans had at least one parent born outside the U.S., and each group had definite views about which side in the war they supported. “Old Stock” Americans sympathized with the British and French “Allies,” as did the Poles, who recognized the war as an opportunity to rid their homeland of German and Austrian domination. The Irish, not surprisingly, opposed the British. Though most Milwaukee Germans were second- or third-generation Americans, they naturally supported kin in the Fatherland, causing patriotic Americans nationwide to question Milwaukee’s loyalties.

Milwaukee was suspect for another reason. It was a stronghold of the Socialists, whose members opposed war as capitalism run amok. Party leaders—Congressman Victor Berger and Mayor Dan Hoan—were not wild-eyed radicals spouting social and political revolution. Rather, they believed in a gradual, practical, peaceful transition to a socialist state. Nevertheless, patriots branded all Milwaukee socialists traitors because of their opposition to the war and because of the large number of German industrial workers who helped fuel the Party’s rise. Berger, a native of Austria, emerged as the symbol of socialist disloyalty.[11]

Milwaukee’s temperature concerning the war was measured when a German U-boat torpedoed the British ocean liner Lusitania in May 1915. More than one hundred Americans were killed, and public opinion throughout the U.S. turned against Germany; Milwaukee, however, remained a hub of support for Kaiser Wilhelm. In addition, Milwaukee Germans increased their criticism of what they viewed as President Woodrow Wilson’s blatant support for the Allies. Alarmed by Milwaukee’s perceived pro-Germanism, the Milwaukee Journal launched a “100% Americanism” campaign in 1916. Despite the Journal’s efforts, by March 1917, patriotic Milwaukeeans feared the city was primed for an uprising. Rumors circulated that 4,000 former German soldiers in the state reserves were waiting to inflict chaos throughout Milwaukee and that the Philip Gross Hardware Company had secretly shipped 7,000 rifles in the middle of the night to pro-German sympathizers. Though a Department of Justice investigation found the rumors baseless, a group of influential citizens contacted the governor, state adjutant general, Secretary of War, and U.S. Army Department commander in Chicago seeking placement of a Wisconsin National Guard regiment at the state fairgrounds should pro-German trouble arise. Government officials dismissed the request as a gross overreaction, but the hysteria grew worse when the U.S. declared war on April 6, 1917.[12]

Many Milwaukeeans were not enthusiastic about joining the fight but nevertheless “did their bit” to support the war. Milwaukee certainly provided its fair share of military recruits. Nearly 49,000 men registered for the draft on June 5, 1917, and many who served distinguished themselves on the battlefield. William “Billy” Mitchell, for example, rose in rank from major to brigadier general by war’s end, receiving the Distinguished Service Cross and Distinguished Service Medal for leading America’s first air corps. And the 32nd Infantry Division—including several Milwaukee units—was the first to pierce the Germans’ “Hindenburg Line” of defense. The French bestowed the nickname Les Terribles upon the 32nd Division, which thereafter was known as the Red Arrow Division.[13]

On the home front, Mayor Hoan fulfilled his official duties, despite his personal opposition to the war. He helped establish the Milwaukee County Council of Defense to oversee and coordinate war-related activities more effectively. Perhaps most remarkable, newspapers reported that the city’s 2,000 taverns closed on draft day in June 1917 to help things run smoothly—the first time in Milwaukee history its drinking establishments voluntarily stopped serving.[14]

Women contributed by collecting hospital supplies, knitting garments, and distributing care packages to departing soldiers. They also worked in factories, filling the void after men joined the military. Across gender lines, Milwaukee’s young and old alike did what they could, easily surpassing assigned goals for every Liberty Loan drive, increasing food production through “Victory Gardens” and abiding by the federal government’s “wheatless,” “meatless,” “lightless” and “gasolineless” restrictions.[15]

Despite these efforts, overzealous patriots saw anti-American bogeymen everywhere—and they needed to be silenced. Socialists were harassed constantly: Victor Berger found garbage thrown on his lawn nearly every day, and the postmaster general stifled freedom of the press, revoking second-class mailing privileges of Berger’s newspaper, the Milwaukee Leader. Dan Hoan carried a gun due to numerous death threats, and during the spring 1918 mayoral campaign, patriots on the Council of Defense tried to force Hoan to step down as chairman. Their ringleader, Wheeler Bloodgood, advocated declaring martial law if Hoan were re-elected, a move that eventually fizzled.[16]

All Milwaukeeans had to watch what they said because neighbors spied on neighbors, students spied on teachers, servants spied on employers, and Department of Justice agents and proxies from the American Protective League spied on everybody, often using extralegal methods to collect information. To its credit, Milwaukee never succumbed to deadly mob violence such as the April 1918 murder of Robert Prager, a German coal miner, in neighboring Illinois. Perhaps the conservative, law-abiding nature of Milwaukee residents prevented this, or maybe the large German population sparked fears of a backlash if super-patriots went overboard. Nevertheless, those being persecuted had nowhere to turn for help; the newspapers, police, judiciary, and federal government were all gripped by patriotic hysteria. In September 1917, a riot in Bay View erupted when an Italian group objected to the pro-war, anti-Catholic harangue of August Guiliani, an Evangelical Methodist minister. Eleven Italians were arrested. While awaiting trial, a bomb exploded in the police station, killing nine people. Prosecutors portrayed the tragedy as an anti-war statement and unjustly connected the eleven Italians to the bombing. The jury convicted all of them, and they were sentenced as many as twenty-five years in prison. In September 1918, employees of the Milwaukee Harvester Works painted four co-workers yellow because they refused to buy more Liberty Bonds. None of the assailants was arrested.[17]

Hysteria gave way to unbridled joy with the signing of the armistice on November 11, 1918. Factory whistles blew, and bells tolled all day. People yelled, laughed, and cried. Yet disillusionment replaced elation as the war’s costs became evident. The scales decidedly tilted toward what was lost rather than what was gained. The human cost alone—nearly 500 dead servicemen plus the 1,100 city residents who died during the Spanish Flu epidemic in fall 1918—drained Milwaukee of untapped potential. Women praised for patriotism as they stepped into male-dominated occupations to meet wartime labor demands were soon laid off when the men returned. Milwaukee’s brewing industry, a vital part of the city’s economic/cultural landscape, was shuttered when wartime strictures enabled Prohibition to become law.

During the war, much of Milwaukee’s German heritage disappeared: 250 German-Americans changed names, feeling embarrassed or threatened because of their ethnicity; the study of German in grade schools was eliminated; and production of German plays and music nearly vanished. It was a low point in American history in terms of protecting civil liberties. Oppression weakened Milwaukee’s labor and Socialist movements, and intolerance lingered well after the war. Ultimately, the war the U.S. fought as a crusade to “make the world safe for democracy” and “end all other wars” accomplished neither.[18]

World War II

In the 1920s and 1930s many Americans became disillusioned with the nation’s involvement in the World War that ended in 1919. They believed that the U.S. had been dragged into a European conflict that did not advance U.S. interests. In the 1930s this disillusionment manifested itself in a peace movement that advocated U.S. non-intervention in world conflicts. Milwaukee socialists, the local chapter of Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, and many students at Milwaukee State Teachers’ College (now UW-Milwaukee) joined the movement and participated in a series of large anti-war rallies and marches. In 1935 thousands of people attended rallies in the city, and throughout second half of the 1930s annual peace marches drew hundreds of people.[19] In 1933 that same disillusionment also prompted a small group of recent German immigrants in the city to establish a chapter of the Volksbund, a pro-Nazi organization. This group believed that Germany had been treated unfairly in the Treaty of Versailles and supported Adolph Hitler’s effort to remilitarize his nation. The German-American Volksbund held rallies in the city and established a camp to practice military drills.[20] However, when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor in 1941 and brought the U.S. into the wars that had been raging in Europe since 1939 and Asia since the mid-1930s, the peace movement and the German American Volksbund virtually disappeared and Americans united behind the war effort.

After the Pearl Harbor attack hundreds of Milwaukee men rushed to recruiting offices to join the fight. In fact, on December 16, 1942, the city broke its single-day enlistment record when at least eight-five men joined the armed forces; 126 joined in a single day before the end of the year.[21] Milwaukee women also volunteered for the military and served in the Women’s Army Corps, WAVES, and other units doing everything from clerical work to nursing to flying cargo planes. An estimated 70,000 Milwaukee-area women and men served in uniform all over the globe. By 1945, 1,900 Milwaukeeans had died serving their nation.[22] Milwaukee not only helped fill the ranks of the armed forces, but the city also helped with military mobilization in other ways. The army briefly operated a flight training school at General Mitchell Field, Marquette University established an army and navy training program, and the Veterans Administration hospital cared for the wounded.[23]

One of Milwaukee’s greatest contributions to the war effort was the production of weapons and machines. Even before the U.S. entered the war, Milwaukee’s industries had converted to war production, receiving $175 million in defense contracts with the U.S. and allied governments. By 1944 the annual output of Milwaukee’s war industries was over $1 billion. These government contracts created an intense need for labor. Initially it was easy for factories to find workers. During the 1930s the Great Depression had thrown thousands of Milwaukee residents out of work and war industries could draw on this large pool of unemployed men. However, by late 1942, as the city’s demand for labor intensified and thousands of men went off to war, an acute labor shortage emerged. Many companies turned to migrants from rural areas, but when the shortages continued, companies hired women and African Americans, whom employers had refused to hire in the 1930s and early 1940s. During the war, they were typically paid less than white men and assigned to unskilled or semi-skilled positions. The war also brought a return of labor-management conflicts. As the labor short supply tightened and corporate’ profits skyrocketed, workers demanded raises. Many workers turned to labor unions to advance their interests; over 80,000 Wisconsin workers were unionized by the end of the war.[24] Workers were able to extracted concessions from employers at the negotiating table, but other times they were forced to go on strike to secure improved wages. Milwaukee workers walked off the job sixty-six times during the war. Most of these strikes lasted less than three days, but they typically won concessions from employers.[25]

The war also changed family life in the city. Many struggled to find adequate housing. The migration to Milwaukee of people seeking war industry jobs magnified the city’s preexisting housing shortage. During the war many families moved in with relatives or friends or crammed into small rented rooms. Others moved into trailer camps without water and electric hook-ups, causing the Milwaukee County government to provide toilets, showers, and washing machines. Adding to the pressure on Milwaukee families was worry over the husbands, brothers, and sisters who went off to war. Of course, most of the absentees were men, and many left behind wives to manage homes on their own. Some of these military wives took jobs in war plants and, in fact, by 1944, 25 percent of Milwaukee’s industrial workforce was made up of women and 20 percent of these working women had children. This shift created great anxiety about unattended children getting into trouble, and law enforcement reported that juvenile delinquency spiked during the war.[26]

While the war created great anxiety, it also unified Milwaukee residents who pulled people together to support the war effort. Over 12,000 people volunteered for civil defense work, acting as air raid wardens who, among other things, would enforce blackouts in case the city came under enemy attack. Fifty-five percent of Milwaukeeans grew their own produce in victory gardens and almost all residents purchased war bonds. Milwaukee citizens also contributed to scrap and rubber drives, served as agricultural workers helping to reduce the farm labor shortage and volunteered at the USO and Red Cross. When the war in Europe finally ended in May 1945 thousands filled the city’s streets to celebrate the victory that Milwaukeeans helped secure.[27]

Korea and Vietnam

Milwaukeeans also experienced America’s other armed conflicts in the second half of the twentieth and early years of the twenty-first centuries, but the city itself was relatively unaffected by these foreign wars. Out of the 800 Wisconsinites who died during the Korean War, just under 200 were from the four-county region, with nearly 150 from Milwaukee County. About a quarter of the Wisconsin’s 1,200 deaths during the Vietnam War came from the Milwaukee metropolitan area.[28] The Vietnam War ignited protests around the country, of course, including at Milwaukee’s largest universities, Marquette and the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. Students on both campuses, sometimes in conjunction with other groups like the Veterans Against the War, conducted sit-ins, marches, moratoria, and other organized—and sometimes violent—protests over the presence on Marquette’s campus of ROTC units and on both campuses of interviewers from Dow Chemical; the incursion into Cambodia and the shootings at Kent State University; and the draft. One of the most dramatic protests of the era took place in Milwaukee on September 24, 1968, when fourteen people broke into the city’s Selective Service office, stole 4,000 draft cards, and burned them in a nearby park. All but two were convicted of burglary, theft, and arson and served short prison sentences.[29]

Footnotes [+]

- ^ Richard N. Current, The History of Wisconsin. Vol. II, The Civil War Era, 1848-1873 (Madison, WI: The State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1976), 282; Robert C. Nesbit, Wisconsin: A History (Madison, WI: The University of Wisconsin Press, 1973), 245; Frank L. Klement, Wisconsin in the Civil War: The Home Front and the Battle Front, 1861-1865 (Madison, WI: The State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1997), 4-7.

- ^ Klement, Wisconsin in the Civil War, 117-120; Jerome B. Watrous, ed. Memories of Milwaukee County: From the Earliest Historical Times Down to the Present, Including a Genealogical and Biographical Record of Representative Families in Milwaukee County (Madison, WI: Western Historical Association, 1909), 502. See also Nesbit, Wisconsin, 244 and 119.

- ^ Klement, Wisconsin in the Civil War, 36-43 and 77-81; “Civil War Draft in Wisconsin,” Wisconsin Historical Society, accessed July 27, 2017.

- ^ Frank Abiel Flower, History of Milwaukee, Wisconsin: From Prehistoric Times to the Present Date, Embracing a Summary Sketch of the Native Tribes and an Exhaustive Record of Men and Events for the Past Century, Describing in Elaborate Detail the City as It Now Is, Its Commercial, Religious, Educational and Benevolent Institutions, Its Government, Courts, Press and Public Affairs, Its Musical, Dramatic, Literary, Scientific and Social Societies, Its Patriotism during the Late War, Its Development and Future Possibilities and Including Nearly Four Thousand Biographical Sketches of Pioneers and Citizens (Chicago, IL: Western Historical Co., 1881), 696; and Klement, Wisconsin in the Civil War, 120-123.

- ^ Current, The History of Wisconsin, 297-299; and Watrous, Memories of Milwaukee County, 593.

- ^ Klement, Wisconsin in the Civil War, 14-19; Nesbit, Wisconsin, 248; Herbert C. Damon, History of the Milwaukee Light Guard (Milwaukee: Sentinel, 1875), 157-161; The Sentinel Almanac and Book of Facts (Milwaukee: The Sentinel Company, 1899), 43-44; and Thomas J. McCrory, Grand Army of the Republic, Department of Wisconsin (Black Earth, WI: Trail Books, 2005), 329-333.

- ^ Damon, History of the Milwaukee Light Guard, 13, and 19-21; and Nesbit, Wisconsin, 247-248.

- ^ Edwin Bentley Quiner, The Military History of Wisconsin (Chicago, IL: Clarke & Company, 1866), 135-6; “History of the 26th Wisconsin Infantry,” Russscott.com, accessed July 27, 2017; “Col. Hans Christian Heg,” Wisconsin Historical Society, accessed July 27, 2017.

- ^ William George Bruce, Builders of Milwaukee (Milwaukee: The Bruce Publishing Company, 1946), 742; Milwaukee Daily Sentinel, May 23, 1861, May 31, 1861, November 8, 1861, November 15, 1861, December 11, 1861, January 11, 1861, January 31, 1862, and February 4, 1862; Sarah Edwards Henshaw, Our Branch and Its Tributaries, Being a History of the Work of the Northwestern Sanitary Commission and Its Auxiliaries during the War of the Rebellion (Chicago, IL: Alfred L. Sewell, Publisher, 1868), 21; Ethel Alice Hurn, Wisconsin Women in the War between the States (Madison, WI: Wisconsin History Commission, 1911), 21-22; and Klement, Wisconsin in the Civil War, 14-15 and 113-114.

- ^ Hurn, Wisconsin Women in the War between the States, 161-162; Milwaukee Sentinel, October 19, 1861, August 20, 1862; Milwaukee Daily Sentinel, October 29, 1861, November 6, 1861, November 21, 1861, and March 9, 1864; Flower, History of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, 740; and Klement, Wisconsin in the Civil War, 113-117,

- ^ John Gurda, The Making of Milwaukee (Milwaukee: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 1999), 204-206, 214-224.

- ^ John Joseph Starzyk, “Milwaukee and the Press, 1916: The Development of Civic Schizophrenia” (M.A. thesis, Marquette University, 1978); Old German Files, Case 8000-1105 and Case 8000-20117, Records of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, Record Group 65, National Archives; William H. Thomas, Jr., Unsafe for Democracy: World War I and the U.S. Justice Department’s Covert Campaign to Suppress Dissent (Madison, WI: The University of Wisconsin Press, 2008), 133-135; Joan M. Jensen, The Price of Vigilance (Chicago, IL: Rand McNally & Company, 1968), 27-28; “Memoranda of Meeting Sunday Night, April 1st,” Charles King Papers, Wisconsin Historical Society; King to General Barry, April 2, 1917, Newton Diehl Baker Papers, Library of Congress, Personal Correspondence, “B” 1917; Charles King, “Memories of a Busy Life,” The Wisconsin Magazine of History 6 (1922-1923): 185-187.

- ^ Joint War History Commission of Michigan and Wisconsin, The 32nd Division in the World War, 1917-1919 (Madison, WI: Wisconsin War History Commission, 1920); Carl Penner, Frederic Sammond, and H.M. Appel, The 120th Field Artillery Diary (Milwaukee: Hammersmith-Kortmeyer Co., 1928): 26-43.

- ^ “Milwaukee Calm as Men Register” and “Saloons Close All Day, First Time on Record” in Milwaukee Sentinel, June 6, 1917; Weekly Report, June 9, 1917, Wisconsin, State Council of Defense, Wisconsin Historical Society; King, “Memories of a Busy Life,” 187-188.

- ^ “Abolish Skirts, Wear Overalls, Man Advocates,” Milwaukee Sentinel, May 20, 1917; “Up To the Women to Fill Men’s Jobs,” Milwaukee Sentinel, July 25, 1917; “Sees Effort to Get Cheap Labor,” Milwaukee Leader, July 19, 1917; “Women Take Places of Men Called to Serve Nation,” Milwaukee Sentinel, August 11, 1917; “Women Prove Capable in Machine Shop Work,” Milwaukee Sentinel, August 15, 1917; Kimberly Jensen, Mobilizing Minerva: American Women in the First World War (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2008); Carrie Brown, Rosie’s Mom: Forgotten Women Workers of the First World War (Boston, MA: Northeastern University Press, 2002), 3-18; Report of the Secretary of the National League for Women’s Service in Wisconsin, March 1, 1918, Edessa Kunz Lines Papers, Marquette University; “Milwaukee Loans U.S. $17,352,000,” Milwaukee Sentinel, June 15, 1917; Paul W. Glad, The History of Wisconsin, vol. V: War, a New Era, and Depression, 1914-1940 (Madison, WI: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1990), 43-45; Robert L. Hachey, “Dissent in the Upper Middle West During the First World War, 1917-1918” (Ph.D. diss., Marquette University, 1993), 186-210; David M. Kennedy, Over Here: The First World War and American Society (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1980), 99-106.

- ^ Edward Kerstein, Milwaukee’s All-American Mayor: Portrait of Daniel Webster Hoan (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1966); Kimberly Swanson, ed., A Milwaukee Woman’s Life on the Left: The Autobiography of Meta Berger (Madison, WI: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 2001); Dan Hoan to Executive Committee, Milwaukee County Council of Defense, March 13, 1918, Daniel W. Hoan Collection, Milwaukee County Historical Society; “Army Law for Milwaukee,” New York Times, March 22, 1918; U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on Military Affairs, Extending Jurisdiction of Military Tribunals: Hearings before the Committee on Military Affairs on S. 4364, 65th Congress, 2nd Session, April 17, 1918, 3-30; Jensen, Price of Vigilance, 120-121.

- ^ Robert Tanzilo, The Milwaukee Police Station Bomb of 1917 (Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2010); Dean A. Strang, Worse than the Devil: Anarchists, Clarence Darrow, and Justice in a Time of Terror (Madison, WI: The University of Wisconsin Press, 2013); “Painting Case Stirs Up Hoan,” Milwaukee Sentinel, September 28, 1918; Hoan to Chief of Police John T. Janssen, September 27, 1918, Daniel W. Hoan Collection, Milwaukee County Historical Society; Kennedy, Over Here, 68; Thomas Fleming, The Illusion of Victory: America in World War I (New York, NY: Basic Books, 2003): 250-251.

- ^ Gurda, The Making of Milwaukee, 225-233; Geoffrey R. Stone, Perilous Times: Free Speech in Wartime, from the Sedition Act of 1798 to the War on Terrorism (New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company, 2004), 4-5; John D. Stevens, “When Dissent Was a Sin in Milwaukee: Law, Watchful ‘Patriots’ Harassed ‘Pro-Germans’ in World War I Days,” Milwaukee Sentinel, March 10, 1966; Gerhard Becker, “The German-American Community in Milwaukee during World War I: The Question of Loyalty” (M.A. thesis, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 1988), 71-78.

- ^ Daryl Webb, “Radical and Patriots: Youth against War in Milwaukee,” Milwaukee County History, 1 (4): 87-92.

- ^ Russell Austin, The Milwaukee Story: The Making of an American City, (Milwaukee: The Milwaukee Journal, 1946), 201; Gurda, The Making of Milwaukee , 306-307.

- ^ Austin, The Milwaukee Story, 203; The Wisconsin Blue Book, 1962, (Madison, WI: The State of Wisconsin, 1962), 257.

- ^ “Milwaukee’s First Year in This War’s One of Service and Shortage,” Journal (Milwaukee, WI), December 6, 1942; Thomas Jablonsky, Milwaukee’s Jesuit University: Marquette, 1881-1981 (Milwaukee: Marquette University Press, 2007), 196-197.

- ^ Robert W. Ozanne, The Labor Movement in Wisconsin: A History (Madison, WI: The State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1984), 63.

- ^ Richard L. Pifer, A City at War: Milwaukee Labor during World War II (Madison, WI: Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 2003), 11, 90-93, 129-32, 193; William Thompson, The History of Wisconsin, vol. VI, Continuity and Change, 1940-1965 (Madison, WI: The State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1988), 93; Joe William Trotter, Jr. Black Milwaukee: The Making of an Industrial Proletariat, 1915-1945, second ed. (Chicago, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2007), 165-169.

- ^ Pifer, A City at War, 30-33, 24-25, 141.

- ^ Gurda, Making of Milwaukee, 312-315; Austin, The Milwaukee Story, 203.

- ^ Milwaukee County Korea War Casualties, Links to the Past.com, last accessed August 6, 2017; Waukesha County Korea War Casualties, Links to the Past.com, last accessed August 6, 2017; “U.S. Military Fatal Casualties of the Vietnam War for Home-State-of-Record: Wisconsin,” National Archives, at Archives.gov, last accessed August 14, 2017; The Vietnam War, Wisconsin Historical Society website, last accessed August 6, 2017.

- ^ “Timeline,” Vietnam War Protests at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee-Archives Department, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee libraries, last accessed August 6, 2017; Jablonsky, Milwaukee’s Jesuit University, 328-333.

For Further Reading

Abing, Kevin. A Crowded Hour: Milwaukee during the Great War, 1917-1918. Mount Pleasant, SC: Arcadia, 2017.

Gilpatrick, Kristin, ed. The Hero Next Door: Stories from Wisconsin’s World War II Veterans. Oregon, WI: Badger Books, 2000.

Keup, Charissa. “Delinquency, Sex, and Milwaukee Girls during the Second World War.” Milwaukee County History 1, no. 4: 75-80.

Luebke, Frederick C. Bonds of Loyalty: German-Americans and World War I. Dekalb, IL: Northern Illinois University Press, 1974.

Pifer, Richard L. A City at War: Milwaukee Labor during World War II. Madison, WI: Wisconsin Historical Society, 2003.

Pula, James S. The Sigel Regiment: A History of the 26th Wisconsin Volunteers, 1862-1865. El Dorado, CA: Savas Publishing, 2014.

Rees, Johnson. “Caught in the Middle: The Seizure and Occupation of the Cudahy Brothers Company, 1944-1945,” Wisconsin Magazine of History 78 (3), 200-18.

Stevens, Michael E., and Ellen Goldlust-Gingrish, eds. Women Remember the War, 1941-1945. Madison, WI: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1993.

Strang, Dean A. Worse than the Devil: Anarchists, Clarence Darrow and Justice in a Time of Terror. Madison, WI: The University of Wisconsin Press, 2013.

Thompson, William. The History of Wisconsin. Vol. VI, Continuity and Change, 1940-1965. Madison, WI: The State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1988.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.