Peace education provides the opportunity to examine values and attitudes, acquire knowledge, and develop skills useful for understanding wars and violence and promoting a culture of peace and global understanding.[1]

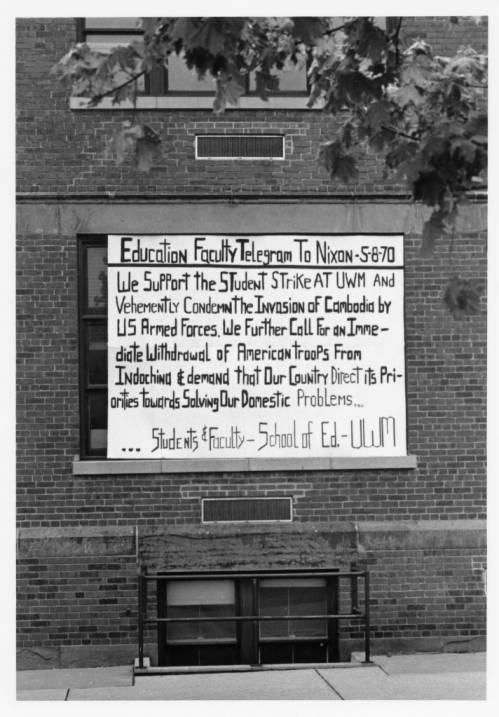

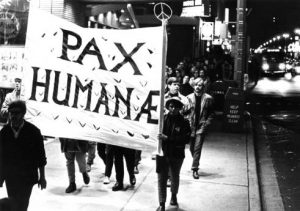

Anti-war education shaped the Civil War era, and continues today: people protested against slavery and war during the Civil War;[2] German settlers pled for neutrality during the Great War;[3] Socialists protested against colonialism and other detriments of war;[4] students held teach-ins during the Vietnam and Iraq wars.

People have engaged in education for peace since the early twentieth century.[5] “The Wisconsin Plan for Peace” was part of the movement to prevent American participation in foreign wars.[6] The Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF),[7] the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Committee on Problems of War and Peace,[8] and the Institute for World Affairs[9] have all promoted education for international understanding. Milwaukee Public Theater has used drama to raise justice issues. Diverse religious communities and the Interfaith Conference of Greater Milwaukee have offered programs on war, peace, and nonviolence, often from an interfaith perspective.

The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee established its academic Peace Studies Certificate Program and offered a course in peace education in 1983,[10] and Marquette University established its Center for Peacemaking in 2007. Other universities have also introduced peace education courses, many from multiple disciplinary perspectives. Faculty from public and private colleges and universities in Wisconsin collaborated during the 1980s nuclear threat to form the Wisconsin Institute for the Study of War, Peace, and Global Cooperation in 1985.[11] The International Rotary Club established its peace fellowship program for graduate studies in 2002.[12]

Peace education for children dates to the late nineteenth century and continues in some form today. Socialists began offering education programs to high school students on democracy and the dangers of capitalism and its relationship to war during the Great War.[13] The Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom developed Learning Peace materials for use in schools between 1972 and 1976.[14] A Peace Education Committee offered an anti-war curriculum to high school students and their teachers throughout a five-county area from 1971 to 1973.[15]

Peace Education in the Milwaukee Public Schools (MPS) deserves special mention. Peacemaking Associates opened in 1974[16] and began offering peacemaking for children programs to teachers and students in Milwaukee Public Schools (MPS), as well as other schools throughout Southeastern Wisconsin.[17] This program was based on the theory that peace education should teach both about and for peace, and include both theoretical and affective learning experiences.[18] At the time, members of the “Coalition for Peaceful Schools” worked for the peaceful and humane desegregation of Milwaukee Public Schools,[19] and in 1976, as a result of the federal desegregation settlement, the MPS Board of School Directors was charged with offering programs supporting this effort for principals, teachers, and students in public and private schools throughout a five-county area of Southeastern Wisconsin. Peacemaking Associates and the Milwaukee Public Schools’ Department of Human Resources collaborated to expand the popular Peacemaking for Children programs as a part of this settlement.[20] Related programs have included Safe & Sound, a community-based, collaborative crime prevention strategy, and anti-bullying, conflict resolution, anti-violence, and peer mediation.[21] In the fall of 1982, members of the local chapter of Educators for Social Responsibility urged the Curriculum Committee of the MPS Board of Directors to implement a curriculum to address the growing nuclear fear among students and their teachers. Committee members chose instead to develop an education for peace program that offered a more holistic perspective. Three years later, MPS became one of the first public school systems in the United States to establish a comprehensive K-12 peace education curriculum. Teachers began using this curriculum with the February 1985 school term. The Peacemaking for Children curriculum first offered in MPS schools in 1974 became the foundation for the MPS K-5 Peace Education Program in 1985.[22] The MPS Peace Education Curriculum was updated in 1995 to address a growing concern about school and community violence.[23]

Both approval and controversy accompany efforts for peace education. Word of mouth helped spread the message of popular peace education programs; still, some suggested that to teach “peace” was unpatriotic, especially during the height of any given war, as well as during the development of the peace education curriculum for students in the Milwaukee Public Schools.[24] Even so, evaluations of the pioneering Peacemaking for Children and Peacemaking for Families programs offered through Peacemaking Associates and of the UWM Peace Studies Certificate Program continue to testify to the effectiveness of these programs to teach both about and for peace.[25]

Footnotes [+]

- ^ See “Peace Education Theory,” accessed June 1, 2017, for an examination about theories and practices related to peace education. For a selective history of Peace Education and Peace Studies in Wisconsin, see Ian Harris, Dick Ringler, Kent Shifferd, and William Skelton, “History of the Wisconsin Institute for Peace and Conflict Studies,” Journal for the Study of Peace and Conflict (Stevens Point, WI: Wisconsin Institute for Peace and Conflict Studies, 1985).

- ^ Martin K. Gordon, “The Milwaukee Militia, 1863-1880,” Historical Messenger of the Milwaukee County Historical Society 24 (March 1968); see also Frank L. Klement and Peter V. Deuster, “The ‘See-Bote’ and the Civil War,” Historical Messenger of the Milwaukee County Historical Society 1-18 (1941-1962), 5-6..

- ^ David A. Shannon, “The World, the War, and Wisconsin, 1914-1918,” Historical Messenger of the Milwaukee County Historical Society 22 no. 1 (March 1966): 23.

- ^ Victor Berger, Milwaukee Leader, June 6, 1917; see also the 1940s pamphlet “What Are We Fighting for?” distributed by the Young People’s Socialist League, Milwaukee Historical Society Archives Department.

- ^ Final Act of the International Peace Conference, The Hague, July 29, 1899, International Committee of the Red Cross website, accessed June 1, 2017.

- ^ Walter I. Trattner, “Julia Grace Wales and the Wisconsin Plan for Peace,” The Wisconsin Magazine of History, (Spring 1961): 203-213.

- ^ Course offerings for peace 1990, Box 2, Folder 14, Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, Milwaukee Branch records, Archives Department, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Libraries.

- ^ University Committee on Problems of War and Peace, Box 26, Folder 14, UW-Milwaukee Campus Committees Collection, Archives Department, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Libraries.

- ^ UW-Milwaukee Institute of World Affairs Records, Archives Department, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Libraries.

- ^ UWM Peace Studies Certificate Program and UWM Peace Education Program, Box 82, Folder 8, UW-Milwaukee Office of the Provost and Vice Chancellor for Academic Affairs Records, Archives Department, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Libraries.

- ^ Wisconsin Institute for the Study of War, Peace, and Global Cooperation, 1985-1990, Box 114, Folder 24, UW-Milwaukee Office of the Provost and Vice Chancellor for Academic Affairs Records, Archives Department, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Libraries. See also the Wisconsin Institute for Peace and Conflict Studies, Box 143, Folder 43, UW-Milwaukee Office of the Provost and Vice Chancellor for Academic Affairs Records, Archives Department, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Libraries.

- ^ Peace fellowships, Rotary website, last accessed June 1, 2017.

- ^ See “Socialists and the Classroom” leaflets, Box 2, File 31, Milwaukee County Historical Society Library, Archives Department.

- ^ Peace Education, Box 6, Folder 1, and Guides for Schools 1985, Box 3, Folder 2, both in Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, Milwaukee Branch records, Archives Department, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Libraries.

- ^ Milwaukee Peace Action Center Records Archives Department, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Libraries.

- ^ Milwaukee Peace Education Foundation Records, 1965-1977, Milwaukee Small Collection 88, Archives Department, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Libraries.

- ^ Records of Peacemaking Associates and the Milwaukee Peace Education Resource Library.

- ^ Birgid Brock-Utne, Feminist Perspectives on Peace and Peace Education (New York, NY: Teachers College Press, 1989).

- ^ Coalition for Peaceful Schools 1977-1981, Box 7, folder 9, Henry S. Reuss papers, Archives Department, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Libraries and. Coalition for Peaceful Schools, 1977-1981, Box 74, Folder 35; and Box 195, Folder 1 and 3 , both Lloyd A. Barbee papers, Archives Department, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Libraries,. Coalition for Peaceful Schools organized in 1976 “in order to promote the peaceful desegregation of Milwaukee Public Schools.”

- ^ Records of Peacemaking Associates and the Milwaukee Peace Education Resource Center.

- ^ Teachers from area schools also adapted material from existing curricula, including “The Friendly Classroom for a Small Planet” developed by the American Friends Service Committee in New York City; “The Conflict Resolution Curriculum” developed by the Madison Center for Conflict Resolution; and the “Learning Peace” curriculum developed by members of the National Office of Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom in Philadelphia.

- ^ For a report on the process undertaken to develop this curriculum, see Jacqueline Haessly, What Shall We Teach Our Children: Peace Education in the Milwaukee Public Schools (Milwaukee: Peace Talk Publications, 1985). This report has been reprinted in various forms in national and international publications.

- ^ Jacqueline Haessly, “Peace Education in the Classroom: Ten Years Later,” in Peace in Action (Arlington, VA: Foundations for P.E.A.C.E, 1995).

- ^ Jacqueline Haessly, What Shall We Teach Our Children, (Milwaukee: Peace Talk Publications. 1985).

- ^ An assessment of the “Peacemaking for Children” and “Peacemaking for Families” education programs offered by Jacqueline Haessly since 1974, both in Milwaukee and in countries around the world, can be found in ‘What Others Are Saying,” in Part Four of Peacemaking: Family Activities for Justice and Peace (Milwaukee: Peace Talk Publications, 2011). See also Connie Popp, “A Piece of Peace: A Program Evaluation of the Peace Studies Certificate Program at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee,” 2002; and Marquette Center for Peacemaking, http://www.marquette.edu/peacemaking/peaceworks.shtml, now available at http://www.marquette.edu/peacemaking/, accessed June 1, 2017.

For Further Reading

Brock Utne, Birgit. Feminist Perspectives on Peace and Peace Education. New York, NY: Teachers College Press, 1989.

Haessly, Jacqueline. Peacemaking: Family Activities for Justice and Peace. Vol. 1. Milwaukee: Peace Talk Publications, 2011.

Haessly, Jacqueline. What Shall We Teach Our Children: Peace Education in the Milwaukee Public Schools. Milwaukee: Peace Talk Publications, 1985.

Harris, Ian M., and Mary Lee Morrison. Peace Education. 3d. ed. New York, NY: MacFarland and Company, 2012.

Harris, Ian, Dick Ringler, Kent Shifferd, and William Skelton. “History of the Wisconsin Institute for Peace and Conflict Studies.” Journal for the Study of Peace and Conflict, Stevens Point: Wisconsin Institute for Peace and Conflict Studies, 1985.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.