Lutherans have been part of Milwaukee’s fabric from its earliest years. But the American Lutheran controversy—the tension between Americanization and maintaining religious identity—is at the core of the Lutheran experience in Milwaukee. Historian Mark Noll described the attempt to maintain an inherited faith in the context of Americanizing as “steering between the Scylla of assimilation without tradition and the Charybdis of tradition without assimilation.”[1]

The massive immigration of Germans to Wisconsin and the Milwaukee area provided a welcoming environment for Lutherans. “Old Lutherans”—those who remained doctrinally conservative as they arrived in the United States—were dissenters from Mecklenburg, Pomerania, and other parts of Prussia in northern Germany. In 1839, Pastor J. A. A. Grabau led about 1,000 Old Lutherans to America; half settled near Buffalo, New York, and about half passed through to Milwaukee. Some of the twenty poor families who reached the Milwaukee area established Trinity Lutheran Church in nearby Freistadt; L.F.E. Krause pastored this church, the oldest Lutheran congregation in Wisconsin. As the 1830s closed, pietistic, low-church Norwegian Lutherans (known as Haugeans) settled in nearby Muskego and organized Muskego Lutheran Church (“Old Muskego Church”) in 1843. By the mid-1840s, two Lutheran groups had congregations in Milwaukee and the surrounding area: the Buffalo Synod organized St. Paul’s in Milwaukee in 1845 and two congregations outside the city (one each in Ozaukee and Washington counties) whereas the Missouri Synod established Trinity (1847) in Milwaukee. At mid-century, yet another group—“New Lutherans”—arrived in Milwaukee; these German Christians accepted the union of Lutheran and Reformed, though each sect retained its unique doctrines and practices. Johannes Muehlhaeuser served these New Lutherans and founded the German Evangelical Lutheran Trinity Congregation in 1849; the congregation was renamed Grace because of the Missouri Synod’s neighboring Trinity congregation. Grace originally was at the west side of the city—“Kilbourntown”—where the majority of Germans lived, but the existence there of ten German congregations of several sects led members to purchase a lot on the east side at the northwest corner of Broadway and Juneau Avenue. Soon, these New Lutherans constituted themselves as the Wisconsin Synod.

Another strand of religious thought with connections to Lutheran beliefs and heritage was a trend toward free congregations—churches rational in dogma and independent of the synods. In 1851, a Lutheran-Reformed group proposed a Freie Gemeinde; Eduard Schroeter, the group’s leader, published The Humanist, stressing independence and individuality of thought. When the group dissolved, the remaining members merged with the Society of Free Men (1854), an example of assimilation without tradition.

Lutherans’ tendency to elevate tradition over assimilation is evident in their zest for parochial schools. Congregation schools—particularly in churches affiliated with the Missouri and Wisconsin synods—were designed to insure religious orthodoxy, and cultural and linguistic continuity. So earnest were Lutherans to school their children that the birth of the school often coincided with the establishment of the congregation. Missouri Synod congregations tried to meet the need for orthodox teachers for Lutheran schools by operating a small teachers’ seminary (1855). Additionally, Henry Conrad of Trinity started a Lutheran high school in 1868 (August Crull was the director). The Wisconsin Synod made plans for its own secondary school (under Dr. Hermann Duemling). The schools first merged and then closed in 1871.

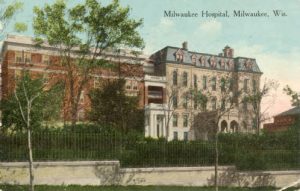

Lutherans also ministered to members’ and other citizens’ medical needs. When cholera swept Milwaukee in the mid-1850s, Johannes Muehlhaeuser of Grace provided care for the suffering. On a larger scale, Pastor William Passavant, a minister serving in Pittsburgh, raised funds to found Passavant Hospital (also called Milwaukee Hospital and Milwaukee Lutheran) in 1863.

In the decades following the Civil War, Lutherans in Milwaukee navigated between their Scylla and Charybdis, growing in numbers and integrating themselves into the community, yet trying to preserve the distinctiveness of the faith. In 1870, about 15 percent of church members in Milwaukee County were Lutheran; in 1890, about 28 percent of church members in the city of Milwaukee identified themselves as Lutheran. In 1881, Missouri Synod Lutherans founded Concordia College (housed at Trinity in Milwaukee) with thirteen students; the next year the college relocated to a permanent campus on 31st Street and, for approximately 80 years, the school provided a high school education and two years of liberal arts studies for students preparing for ministry in the Missouri Synod. Concordia added programs of study, became a four-year accredited university, and in the 1980s relocated to the former campus of the School Sisters of Notre Dame in Mequon. (In 1973, another institution of higher education with faith-based roots, Wisconsin Lutheran College, was founded by members of the Wisconsin Evangelical Lutheran Synod.)

George Brumder, a member of Grace, arrived in Milwaukee from Alsace-Lorraine in 1857; he sold Bibles and hymnals at a Lutheran bookstore located in today’s Pere Marquette Park. In 1873, Brumder and other German Protestants incorporated the German Protestant Printing Company to publish the Germania, a Republican-leaning weekly (later a daily) with a Christian viewpoint; it became the largest German-language paper in the United States. Brumder built the formidable eight-story Germania Building at Wells and North Plankinton Avenue (called the Brumder Building between 1918 and 1981) to house his publishing enterprises.

Another Lutheran immigrant who profoundly altered the financial and physical landscapes of Milwaukee was Prussian John Pritzlaff. Between 1850 and his death in 1900, Pritzlaff created a massive hardware wholesale business; halfway through his tenure, Pritzlaff built the first two sections of the monstrous Pritzlaff Building (designed by John Rugee) on Plankinton Avenue. By the advent of World War I, Pritzlaff Hardware occupied a 300,000 square-foot Cream City brick structure and was one of the largest hardware wholesalers in the Midwest. Robert Nesbit, in his volume in The History of Wisconsin series, attributes some of Pritzlaff’s success to the hardware mogul’s expectation that “other members of the extensive German business community [do] business with him, particularly fellow members of his [Trinity] Lutheran church congregation.”[2] In 1868 Pritzlaff gave Trinity its present property on the corner of North Ninth Street and West Highland Avenue. A decade later, one thousand people attended the cornerstone-laying, and the present structure (designed by Magdeburg-born Frederick Velguth) was completed in 1880. The city’s Historic Preservation Commission simply describes the structure as “architecturally significant…the city’s best example of a German-inspired, High Victorian Gothic style church.”[3]

Lutherans in Milwaukee followed contradictory impulses: they flirted with mergers between and among synods, yet isolated themselves from each other and from other Protestant churches. A conspicuous example of this tension and separateness is evident in the histories of and rivalries between Trinity (Missouri Synod) and St. John’s at North Eighth and West Vliet (Wisconsin Synod). Pastor Ludwig Dulitz and a group of German Lutheran families established St. John’s in 1848 and expressed interest in joining the Missouri group, but the proximity of Trinity and opposition from members of both congregations ruled out such an association. In 1857, the congregation at St. John’s joined the Wisconsin Synod. St. John’s, like Trinity, experienced exuberant growth in the three decades after its founding, building parochial schools (1871 and 1877) and surpassing 2,500 members. Also like Trinity, St. John’s desperately needed a larger worship space; in 1889, the church hired German-born architect Herman Paul Schnetzky to design their own cathedral-like church, what the Historic Preservation Commission calls one of the city’s “finest examples of High Victorian Gothic ecclesiastical architecture” and “a fine example of a prosperous Victorian-era Protestant church complex.”[4] Subsequent pastors at St. John’s served as presidents of the Wisconsin Synod: Johannes Bading (1860-1889, with a three-year sabbatical) and John William Otto Brenner (1933-1953).

The desire to express like-mindedness and work together saw some success in 1872 when a half-dozen Midwestern Lutheran groups founded the Evangelical Lutheran Synodical Conference of North America. Representatives of the synods met at St. John’s in Milwaukee and agreed to share clergy and educational institutions, and to cooperate on mission work; the conference finally dissolved in 1967, though isolating and introverting tendencies—what Robert Nesbit called an “addict[ion] to schismatic proliferation”—plagued the group from the 1940s.[5] St. John’s Bading served as president of the Synodical Conference from 1882 to 1912.

Lutherans in Milwaukee exerted themselves politically toward the end of the century when Wisconsin’s Republican governor, William Dempster Hoard, promoted and signed the so-called Bennett Law (named for the Republican assemblyman who sponsored the bill), which was designed to compel children and young people to attend a minimum amount of school annually and to protect children from exploitative employment practices. But the Bennett Law also had a section that many German Lutherans found objectionable: “No school shall be regarded as a school under this act unless there shall be taught therein, as part of the elementary education of children, reading, writing, arithmetic and United States history, in the English language.” Lutherans in Milwaukee and throughout the state organized to insure Hoard would not be re-elected, Democrats would control the state senate and assembly, and the legislature would repeal the Bennett Law, which was, according to state Republicans after their stunning electoral defeat, “a silly sentimental and damned useless abstraction, foisted upon us by a self-righteous demagogue.”[6] While German Lutherans in Milwaukee did exercise political muscle during the Bennett Law fight, one of the striking characteristics of Lutheranism—German or other—in Milwaukee is its minimal political influence given rather sizeable numbers.

While many German Lutherans fought the Bennett Law and demonstrated their children spoke English in their parochial schools, those same Lutherans continued to worship in German. But a modest Anglicizing movement arose in fin de siècle Milwaukee when the English Evangelical Lutheran Synod of the Northwest (rooted in Minneapolis and St. Paul) used its Home Mission committee to found an English-language congregation in Milwaukee. The Rev. Dr. William K. Frick actualized his slogan, “The Faith of the Fathers in the Language of the Children,” in founding the Church of the Redeemer in early 1890; the congregation worshipped at Pioneer Hall on Grand Avenue and is now located on Nineteenth and Wisconsin. By 1910, Milwaukee was home to six English-language Lutheran churches.[7]

As the twentieth century opened, the Missouri and Wisconsin synods resurrected the idea of Lutheran secondary education in Milwaukee and established Lutheran High School in 1903; twenty-one girls attended classes at Immanuel Lutheran School at North Avenue and Twelfth Street. As the student body grew, the school relocated to Thirteenth and Vine, housed first in the former Wisconsin Synod seminary, then erecting a new brick structure at that same location. Due to doctrinal differences between the Missouri and Wisconsin synods, Lutheran High School was sundered in 1951. This tendency among Lutherans to splinter created what became two thriving schools: Milwaukee Lutheran High School (Missouri Synod, located on Grantosa Drive) and Wisconsin Lutheran High School (Wisconsin Synod, located at Glenview and Bluemound).

During the same time that Pastor Johannes Bading was a leader among conservative Lutherans, his son Gerhard served Milwaukee as municipal health commissioner (1906-1910) and as mayor (1912-1916). As the city’s top doctor, Gerhard Bading established tests for bovine tuberculosis and, according to The Pharmaceutical Era, “started a relentless war on druggists who persist in selling large amounts of cocaine.”[8] Bading’s mayoralty was an interruption in Milwaukee’s thirty-year experience with Socialist mayors; indeed, Bading was a “fusion” candidate, a compromise candidate Republicans and Democrats could agree upon in their efforts to defeat Socialist Emil Seidel in 1912.

During World War I, some Lutherans felt pressure from Americanizers who perceived German-Americans to be disloyal hyphenates. Lutherans affiliated with the Missouri and Wisconsin synods strongly desired to retain German as the language of their faith, fearing the “imprecision” of religious belief in America stemmed from the “homogenizing influence” of the English language.[9] But Lutherans in general accepted the authority of the state when it did not impinge on matters of faith and doctrine. Not surprisingly, the issue of prohibition later caused strong and divergent reactions among Lutherans. Scandinavian Lutherans tended to be more pietistic and revivalistic; Swedish Lutherans (Augustana Synod) and some Norwegian Lutherans were committed to temperance and later to prohibition. German Lutherans, on the other hand, generally decried pietism and saw legislative limits upon alcoholic consumption as an “outside cause…hypocrisy and cant” and a “perforation of bungholes.”[10] Lutheran response to the push for women’s suffrage was not unlike its response to prohibition: the more pietistic Scandinavian Lutherans tended to oppose the Nineteenth Amendment.

Two Lutheran organizations born in the 1950s contributed substantially to the quality of life in Milwaukee. In 1952, Albert Siebert, owner of Milwaukee Electric Tool Company, donated his share of the company to create the Siebert Lutheran Foundation in order to fund ministries of Lutheran churches and organizations. Examples of the foundation’s benevolence in Milwaukee—it has granted three to four million dollars a year for the past couple of decades, primarily in southeastern Wisconsin—are support for urban ministries among Hispanics and Hmong, Lutheran schools, food pantries, and summer and year-long youth programs. In 1956, Lutherans concerned about the needs of aging Milwaukeeans founded the United Lutheran Program for the Aging; in the early 1960s, ULPA (affiliated with the Greater Milwaukee Synod of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America) constructed Luther Manor in Wauwatosa. At the present time, Luther Manor’s campuses in Wauwatosa, Mequon, and Grafton provide retirement and assisted living, adult day services, skilled nursing and rehabilitation services, and hospice care.

In the early 1960s, The Milwaukee Journal reported that the number of Lutherans in the county grew 2.3 percent in the preceding decade (slightly ahead of the growth of population in the county), so that 15.7 percent of county residents identified themselves as Lutheran. But the news was less hopeful regarding churches in the center of the city: 26 congregations in the two-mile center city radius experienced “heavy losses” and 51 churches in the next 2.5 miles out saw small losses. Growth in the number of Lutherans in Milwaukee—“strong gains”—came in 115 congregations outside the 4.5-mile center city radius. The study acknowledged Milwaukee’s changing demographics when it urged efforts to recruit African Americans to join Lutheran churches while condemning the “unwillingness” of many whites to accept blacks as neighbors and “social companions.”[11] Augustana Lutheran Church, a Swedish Lutheran church on Milwaukee’s northwest side, had constructed a new building and claimed 650 members at the time of the survey; by 1970, the neighborhood was 90 percent black and the Lutheran congregation sold its facility to Antioch Baptist Church. At the same time, the Lutheran synods continued to try to hold on to their young adult members; a 1968 Journal article noted a “proliferation of Lutheran groups on campuses,” identifying three independent student centers at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, all on the same block of East Kenwood Boulevard.[12]

A number of unrelated events in the 1980s highlight the tradition-assimilation tension facing Lutherans in Milwaukee. While Lutherans nationally had a tendency to squabble over doctrinal matters, and further isolate and insulate themselves from each other and the larger society, a merger of two of America’s major Lutheran groups created a new force in American Lutheranism. In 1988, the American Lutheran Church and the Lutheran Church in America, together with the much smaller Association of Evangelical Lutheran Churches (dissidents who separated from the Missouri Synod in the 1970s) joined forces to create the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America. The City of Milwaukee expended considerable resources trying to persuade the new church—by far the largest group of American Lutherans—to locate their national headquarters in Milwaukee. A Journal editorial suggested that Milwaukee had much to offer (reasonable costs to locate the headquarters, a healthy ethnic mix, a promised grant of one million dollars from the Siebert Foundation) and boasted that “Milwaukee enthusiastically wants them here.”[13] Indeed, one of the city’s boosters claimed that the Siebert grant was “the diamond that gives our proposal the sparkle that may well set it apart from other cities under consideration.”[14] But the ELCA chose Chicago. According to “Lutherans Say No to Milwaukee” in the Journal, the “chief reason, apparently, was Milwaukee’s image as a—gulp, sob—hick town.”[15]

Milwaukee’s demographics and how some Lutherans responded to them may be indicative of the challenge of assimilation. In 1988, the newly-constituted ELCA reduced (by 8-10 percent) church-wide financial support to Milwaukee’s “Inner City” churches. While the church “repeatedly…stressed a strong commitment to reaching out to racial and ethnic minorities in its goal to become an ‘inclusive’ church,” it was “long on rhetoric and short on delivery,” according to the director of the Milwaukee Lutheran Coalition.[16] An example of how some Lutherans struggled with assimilation, liberal Lutherans abandoned some of their faith’s traditions in ordaining women as pastors. The American Lutheran Church and the Lutheran Church in America had ordained women since 1970, but Milwaukee’s Pastor June Nilssen (of Ascension) in 1985 became the country’s first female senior pastor at a Lutheran congregation with several ministers.

The Milwaukee Parental Choice Program (MPCP), begun in 1990 (and by the 1998-1999 school year having survived a court challenge), has had a profound effect on Lutheran education in the city and county. Many Missouri Synod and Wisconsin Synod congregations have maintained congregational schools since those Lutherans first founded their parishes in Milwaukee, but both groups (not unlike Roman Catholics) have experienced precipitous drops in school enrollments throughout the United States. But the MPCP has, to a large degree, reversed that trend in Lutheran schools in Milwaukee. In fact, many of the Milwaukee schools affiliated with the two Lutheran bodies (Missouri and Wisconsin) who historically trumpeted the separation of church and state now rely on “state” money for their “church” schools’ survival.[17]

Historian Mark Noll has suggested that, in the context of American history, Lutherans “entered into a desert sojourn, as they once again became a relatively isolated religious tradition.”[18] While the Lutheran experience in Milwaukee provides a modest counterexample to Noll’s assertion, it is evident that the tension between maintaining religious identity and Americanization continues to shape the idea and presence of Lutheranism in Milwaukee. Even in Milwaukee’s historically genial religious environment, Lutherans have struggled to preserve doctrinal distinctiveness and to create an American identity.

Footnotes [+]

- ^ Mark Noll, The Old Religion in a New World: The History of North American Christianity (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2002), 252.

- ^ Robert Nesbit, Industrialization and Urbanization, 1873-1893, vol. III. The History of Wisconsin : (Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1985), 217.

- ^ Milwaukee Historic Preservation Commission, “Final Historic Designation Study Report: Trinity Lutheran Church Complex” (2002), 3.

- ^ Milwaukee Historic Preservation Commission, “Historic Designation Study Report: St. John’s Evangelical Lutheran Church Complex” (1990), 3.

- ^ Nesbit, Industrialization and Urbanization, 522.

- ^ David Schroeder, “‘Paddling Their Own Canoe’: Wisconsin Synod Lutherans in Milwaukee during the Bennett Law Contest,” Milwaukee History 26, nos. 3-4 (Fall-Winter 2003): 72, 76.

- ^ Paul Roth, Story of the English Evangelical Lutheran Synod of the Northwest: Synod’s Jubilee, 1891-1941 (s.l.: n.p., n.d.), 23.

- ^ The Pharmaceutical Era 37, no. 1 (January 3, 1907): 12.

- ^ Paul Glad, War, a New Era, and Depression, 1914-1940, vol. V, The History of Wisconsin: (Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1990), 77.

- ^ Glad, War, a New Era, and Depression, 95.

- ^ David Runge, “Milwaukee Lutherans Increase, Study Shows,” Milwaukee Journal, February 7, 1963.

- ^ David Runge, “Merger Sought for Campus Lutheran Organizations,” Milwaukee Journal, October 21, 1968.

- ^ Editorial, “Milwaukee Offers Much to Lutherans,” Milwaukee Journal, August 27, 1986.

- ^ Thomas Collins, “$1 Million Incentive Offered to Lutheran Church,” Milwaukee Sentinel, January 30, 1986.

- ^ “Lutherans Say No to Milwaukee,” Milwaukee Journal, June 28, 1986.

- ^ Mary Beth Murphy, “Lutheran Churches Fearful of Cuts,” Milwaukee Sentinel, October 24, 1988.

- ^ School Choice Wisconsin, “The Impact of the Milwaukee Parental Choice Program on Enrollment in Catholic and Lutheran Schools,” 2014.

- ^ Noll, Old Religion, 243.

For Further Reading

Conzen, Kathleen Neils. Immigrant Milwaukee, 1836-1860: Accommodation and Community in a Frontier City. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1976.

Glad, Paul. War, a New Era, and Depression, 1914-1940. Vol. V, The History of Wisconsin. Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1990.

Gustafson, David. Lutherans in Crisis: The Question of Identity in the American Republic. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1993.

Nelson, Clifford E., ed. The Lutherans in North America. rev. ed. Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1980.

Nesbit, Robert. Industrialization and Urbanization, 1873-1893. Vol. II, The History of Wisconsin Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1985.

Noll, Mark. The Old Religion in a New World: The History of North American Christianity. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2002.

Schroeder, David. “‘Paddling Their Own Canoe’: Wisconsin Synod Lutherans in Milwaukee during the Bennett Law Contest,” Milwaukee History 26, nos. 3-4 (Fall-Winter 2003): 66-77.

Still, Bayrd. Milwaukee: The History of a City. Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1985.

Wentz, Abdel Ross. A Basic History of Lutheranism in America. rev. ed. Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1964.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.