Known variously as the “Inner Core,” “Sixth Ward,” and (pejoratively) “Little Africa,” among other names, Bronzeville was the historic core of African-American Milwaukee on the city’s Near North Side. Racial segregation roughly defined its boundaries along State Street, North Avenue, North 3rd Street (now Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Drive), and North 12th Street.[1] Milwaukeeans also use the designation “Bronzeville” to refer more broadly to the African-American occupied areas of the city’s North Side, an echo of how the moniker is used in Chicago. One observer described the neighborhood as “a city within a city full of leadership, a sense of community, and a focus on entrepreneurship.”[2]

Previously part of the Kilbourntown settlement and home to German and Eastern European Jewish immigrants through the nineteenth century, Bronzeville was one of the oldest parts of the city. African-Americans who arrived in Milwaukee in the early-to-mid twentieth century concentrated in Bronzeville.

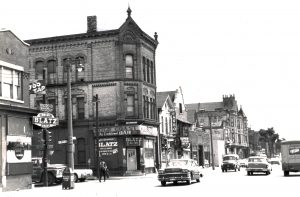

Although 3rd, 12th, and Winnebago streets were important neighborhood commercial areas, Walnut Street was the heart of Bronzeville. It was lined with a variety of African-American businesses, including hotels, restaurants, markets, funeral parlors, barber shops, pool halls, and taverns, as well as the offices of lawyers, physicians, real estate dealers, and organizations.[3] Bronzeville residents enjoyed a vibrant array of social and community engagement opportunities organized by the Booker T. Washington YMCA, the Lapham Park and Fourth Street social centers, the Prince Hall Masons, the Near North Side Businessmen’s Advancement Association, and the National Pan-Hellenic Council of Milwaukee. Informal entertainment included philosophical discussions and speakers at the Lapham Memorial rock and movies and stage shows at the Regal Theater.[4] Fourth Street School (now Golda Meir), Ninth Street School, Roosevelt Junior High, and North Division High School served neighborhood children. Bronzeville produced many notable professionals, including civil rights activist and educator Dr. Howard Fuller, journalist Richard G. Carter, and alderwoman and judge Vel Phillips.

Bronzeville supported a diverse faith community. Residents worshipped at St. Mark African Methodist Episcopal Church, St. Matthew Christian Methodist Episcopal Church, St. Benedict the Moor Catholic Church, Greater Galilee and Calvary Baptist churches, Morris Memorial Church of God in Christ, and a host of storefront churches. The Nation of Islam’s Muhammad Mosque Number Three stood on McKinley Boulevard starting in 1935.[5]

Bronzeville was the center of Milwaukee’s jazz scene. Major clubs on Winnebago and Walnut Streets hosted nationally famous artists, including Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, and Billie Holiday, and budding local greats, like Bunky Green and Willie Pickens.[6] A flourishing underground economy in bootlegging, prostitution, and gambling also supported neighborhood taverns, clubs, and restaurants.[7]

The construction of the North-South (Interstate 43) and Park East freeways destroyed many Bronzeville homes and businesses, displaced numerous residents, and disrupted community life in the 1960s.[8] Although less violent than disturbances that erupted in other American cities, the civil disorder of 1967 also caused lasting physical and social damage to the Bronzeville community.[9]

In more recent years, as some longtime residents moved out, “Bronzeville” has been reimagined as distinct neighborhoods, including Haymarket, Hillside, Halyard Park, and Triangle North. Organizations like the Walnut Area Improvement Council and Walnut Way Conservation Corp. and the informal monthly Walnut Street Social Gathering Club sustain Bronzeville’s legacies. In 2005, the city introduced plans for a new Bronzeville Cultural and Entertainment District, a public-private endeavor to create a tourist destination centered on North Avenue between North 7th Street and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Drive.[10]

Footnotes [+]

- ^ Joe William Trotter, Jr., Black Milwaukee: The Making of an Industrial Proletariat, 1915-45, 2nd edition (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2006), 21-24; Patrick D. Jones, The Selma of the North: Civil Rights Insurgency in Milwaukee, reprint edition (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2010), 19; John M. McCarthy, Making Milwaukee Mightier: Planning and the Politics of Growth, 1910-1960, (DeKalb, IL: Northern Illinois University Press, 2009), 38; Ivory Abena Black, Bronzeville: A Milwaukee Lifestyle (Milwaukee: The Publishers Group, 2006), 11.

- ^ Black, Bronzeville, 12. See also, Bronzeville Milwaukee/The Walnut Street Community, Wisconsin Historical Markers, last accessed April 19, 2018.

- ^ Black, Bronzeville, 15; Reuben K. Harpole, “Introduction,” in Milwaukee’s Bronzeville: 1900-1950, by Paul H. Geenen (Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2006), 8; Normajean C. Sims, “In Honor of Lower Walnut Street Businesses and People Who Made Bronzeville Happen,” in Bronzeville: A Milwaukee Lifestyle, by Ivory Abena Black (Milwaukee: The Publishers Group, 2006), i-ii.

- ^ The Lapham Memorial Rock was located outside of Roosevelt Junior High School on 8th and Walnut Streets, and was later moved near the Lapham Building on the campus of the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. The Regal Theater was located near the corner of 7th and Walnut Streets. Richard G. Carter, “In My Midwest Hometown, Walnut Street Was Our Harlem,” New York Amsterdam News, June 18, 2009.

- ^ The Nation of Islam Muhammad Mosque #3, “The Nation of Islam in Milwaukee, A Brief History,” Muhammad Mosque #3 website, http://www.mosque3.org/history.html, now available at https://www.mosque3.org/page-1, last accessed October 30, 2018.

- ^ Benjamin Barbera, “An Improvised World: Jazz and Community in Milwaukee, 1950-1970” (Master’s thesis, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2012), 40-47.

- ^ Harpole, “Introduction,” 9.

- ^ Niles William Niemuth, “Urban Renewal and the Development of Milwaukee’s African American Community: 1960-1980” (Master’s thesis, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2014); Black, Bronzeville, 20-21.

- ^ Frank A. Aukofer, City with a Chance. A Case History of Civil Rights Revolution (1968; Milwaukee: Marquette University Press, 2007), 21-27; Jones, The Selma of the North, 143-148; The NAACP Youth Council also launched their “Black Christmas” campaign boycotting Christmas holiday shopping and celebrations in late 1967. Intended to draw more attention to the open housing movement, the boycott further hurt Bronzeville businesses and alienated many middle-class neighborhood residents. Jones, The Selma of the North, 204-205.

- ^ Mark Doremus, “City Touts Redevelopment Prospects for Bronzeville Cultural and Entertainment District,” Milwaukee Neighborhood News Service, March 17, 2014.

For Further Reading

Barbera, Benjamin. “An Improvised World: Jazz and Community in Milwaukee, 1950-1970.” Master’s thesis, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2012.

Black, Ivory Abena. Bronzeville: A Milwaukee Lifestyle. Milwaukee: The Publishers Group, 2006.

Carter, Richard G. “In My Midwest Hometown, Walnut Street Was Our Harlem.” New York Amsterdam News, June 18, 2009.

Geenen, Paul H. Milwaukee’s Bronzeville: 1900-1950. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2006.

Jones, Patrick D. The Selma of the North: Civil Rights Insurgency in Milwaukee. Reprint edition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2010.

Niemuth, Niles William. “Urban Renewal and the Development of Milwaukee’s African American Community: 1960-1980.” Master’s thesis, University of Wisconsin Milwaukee, 2014.

Trotter, Joe William, Jr. Black Milwaukee: The Making of an Industrial Proletariat, 1915-45. 2nd edition. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2006.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.